20 AUGUST 1994 is a date of special significance for David Busst.

The game itself was far from a classic. You won’t see it replayed on one of the sports channels anytime soon.

It was the opening day of the Premier League season, and in front of 10,962 people at Highfield Road, Coventry and Wimbledon drew 1-1.

It was the day Busst scored his first-ever Premier League goal, an equaliser that salvaged a point for his side and got the season off to a reasonable start.

It was also a moment where Busst truly felt he was living the dream.

I remember being in a pub in Birmingham,” he tells The42. “It was on Match of the Day, which I’d always watched as a kid. All of a sudden, I was on there, with a little clip they were showing, probably with Des Lynam (hosting).”

As was the case with many footballers in that era, Busst rose through the ranks the hard way. He began his career in the unforgiving world of non-league football, playing for Moor Green in his native Birmingham. By the time he got his big move to Coventry, he was 25 and working in insurance. Suddenly, he was a full-time footballer getting advice from legendary English defender and then manager of the Sky Blues, Terry Butcher.

The side had finished just two points above the relegation zone the season before under Don Howe, while Busst’s move to Coventry coincided with the inaugural season of the Premier League.

In his first two campaigns at the club, the defender’s progress had been slow. He made a respectable 10 appearances in the 1992-93 season, but appeared just three times the following year.

That Wimbledon goal, however, seemed to give Busst a new lease of life, as from that point on, he was a far more regular presence in the heart of Coventry’s defence, making a further 37 appearances in the next two seasons during the tenures of Phil Neal and later Ron Atkinson, and scoring three more goals in the process. The Sky Blues, meanwhile, continued to hover around the lower half of the table and precariously close to the relegation zone at times, while always doing enough to survive.

Despite their struggles, there were some good players in that Coventry side. Busst cites Dion Dublin and Paul Williams as the two best players in the team, while also describing the Zimbabwe international Peter Ndlovu — now somewhat of a cult figure — as “the most gifted footballer that I’ve ever played with”.

He continues: “Peter was so quiet and shy when he first came over from Zimbabwe and I joined just after Peter. He had broken English, but as soon as he got that ball at his feet, he was only wafer thin, but he had so much balance and a turn of pace. You look at some of the iconic games of Coventry, you know — the hat-trick he scored at Anfield. And he spent a good season in the reserves as well, where I sometimes played with him.

“I speak to him on Twitter now and again. He’s bulked up a little bit. The last time I spoke to him he was doing some coaching in Bulawayo. Coventry signed him from Highlanders FC when they went on a tour of Zimbabwe. It was him and his brother Adam as well, who unfortunately passed away a couple of years ago.”

The globalisation of the Premier League was still in its infancy back then, with squads still largely dominated by British and Irish players, making unique foreign talents such as Ndlovu often seem relatively exotic and unpredictable by comparison.

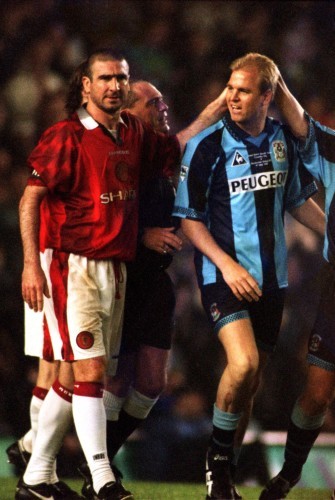

Manchester United’s accomplished French attacker Eric Cantona was another enigmatic and highly distinctive presence in the English game, owing largely to his instinctive brilliance on the field and frequently odd behaviour off it.

Busst describes Cantona, along with Alan Shearer, as the best footballer he ever played against, though the encounter with the former was fleeting in a game that ended for the then-28-year-old defender in horrific circumstances.

I played against Eric Cantona but I was only on the pitch 87 seconds,” he says. “I can’t really claim that because I never really had contact with him. I think I stood next to him. We got a corner, I ran up the other end and that was the closest I got to him.”

The corner in question led to the moment that ultimately ended Busst’s career amid traumatic scenes that all of the 50,000-plus in attendance at Old Trafford that day 21 years ago will have struggled to erase from their memories ever since.

Noel Whelan’s header from an Ally Pickering corner was parried by United goalkeeper Peter Schmeichel. Busst, up from the centre of the defence, charged towards the rebound at speed. An unfortunate collision, however, left the Coventry player screaming in agony. He had broken his tibia and fibula, as his right leg twisted in sickening fashion.

Schmeichel and others shielded their eyes from the gruesome sight. Blood drenched the turf inside the penalty area, while the game was delayed for 15 minutes as the player was assisted by medical staff.

United, on their way to reclaiming the league title they had surrendered the previous season to Blackburn, ultimately won the game 1-0 thanks to a 47th-minute Cantona goal, but the outcome was inevitably overshadowed by Busst’s injury. Some of the players involved reportedly required counselling after witnessing this horrific accident.

Busst, meanwhile, feared the worst as he departed the field on a stretcher.

Denis Irwin caught me on the inside of my ankle (as we went for the ball). There was no malice in it. It was just where the ball was, where we all landed, pressure and forces from different sides.

“So Denis came, he had a block tackle on the inside of my right ankle. Brian McClair was coming the other side because the ball was just bouncing up and he’s coming in with a block tackle around about my right shin on the outside. And then obviously the leg’s in the middle and when two forces in opposite directions come in, then the result is inevitable.

I remember saying to (Coventry teammate) Gordon Strachan as we were coming off the pitch, ‘that’s it now’. I knew my leg was broken, I didn’t know the extent of it.

“He said ‘don’t be silly, you’ll be back,’ and stuff like that. But I was thinking from an age point of view. I would have been 29 going into the next season. I wasn’t like a young 20-year-old.

Obviously, we found out about the complications afterwards, and that was that.”

Yet as gruesome as the injury was, the break in itself was not what stopped Busst from playing again. Instead, an infection that resulted is what ensured any subsequent efforts to return to professional football would ultimately be doomed.

I had a thing called compartment syndrome. It’s a bit like when you get a dead leg. A dead leg is bleeding in the inside of the muscle and the pressure builds up. If you don’t release that pressure, basically they have to. All the way down the right side, the tibia and fibula, there’s a muscle that goes all the way down there to split that and that’s when the infection got all the way into the muscle, which then attacked the tendons that pull my foot up. So then the MRSA resulted in me having four of my five tendons cut away because they were infected. And I was left with one that pulled up my big toe.

“An operation I had a couple of years afterwards was the best one because I was left with a dropped foot because of the tendons being cut. Then I had corrective surgery, fused them all together, they just pulled on my big toe, so it’s not as obvious as it would have been and allows them to run, walk and jog.

The break itself, no matter how horrendous it looked, was no different to a lot of the ones. You don’t see too many to be fair. Imagine how many games of football there are. It is few and far between. They just highlight it more when someone has a serious injury. The bones in nature, they’re joined back together somehow, they knit back and grow back in. So if you don’t have any soft tissue complications or open wounds, then there’s no reason why you can’t come back (from the injury).”

A number of other footballers have experienced similar setbacks, though few if any have suffered Busst’s level of misfortune thereafter.

Djibril Cisse, Henrik Larsson, Eduardo and most recently, of course, Ireland defender Seamus Coleman have all suffered leg breaks during their respective careers.

Provided there are no complications, Coleman could be back playing by around Christmas time or early in the New Year. What message would Busst give to the Everton right-back as he begins the arduous and at times deeply frustrating road to recovery?

My advice would be to set small, achievable goals. As soon as you get out of plaster, you start walking. After physio, you start jogging.

“It might be realistic goals like that, which he can set himself. Three months, he’s out of the plaster doing light training, a month after that, he’d doing light running, just take it month-by-month, using the advice of the physios and listening to them, not rushing anything.

With Seamus, (the break has) remained inside the skin as far as I know. It’s just a case of the bones knitting back together. The bones will calcify — they’ll actually make it stronger in and around where the break is. It’ll actually be a little stronger than it was before.”

For Busst, however, recovering from his accident was anything but straightforward and it required considerable patience. Nevertheless, he was ultimately left feeling somewhat relieved, as there was a suggestion at one point that he was in danger of having to get the leg amputated.

It just wouldn’t heal,” he recalls “I had 10 operations in 12 days and they’d be going in cleaning out and things like that. After a couple of weeks, the blood supply that was down to make the bones heal and all the soft tissue, there just wasn’t a supply. They said if they couldn’t correct that, they may have to cut it from the knee down because it would just go gangrene I suppose.

“Then I went down for an operation where they were going to have to take a muscle out of my back. It’s was like a last-ditch one, put it into my calf, connect it all up and then hopefully that would work.

When I came out from that operation, they hadn’t taken the muscle out of my back or anything. They said when they opened it up again, it showed signs of healing. They were happy it was going to recover on its own, so that was a very big positive step forward.”

In total, Busst would undergo 22 operations following the injury.

The last four were corrective surgeries and the majority of them were in the first three months. When I was first in the hospital, I was there for six weeks. I think it was 14 or 15 operations in those six weeks. Over the next three months, the pin they put in got infected as well. They had to put it in, then take it out.”

He did play one more match for Coventry against Manchester United — his testimonial in front of a sold-out Highfield Road, with England internationals Paul Gascoigne and Les Ferdinand making guest appearances for the Sky Blues.

Busst was not the only footballer who would never play again following that 16 May 1997 match — it also proved to be Eric Cantona’s final game before announcing his retirement at the surprisingly young age of 30.

I’ve still got Eric’s shirt, which he signed for me,” Busst adds. “His last shirt in the Premier League I think John Moncur had, because they played West Ham the last day of the season. He played against us a week later and wore two shirts in that game.”

Almost 20 years on from that emotional evening, Busst seems content in life, despite a picture of his still pretty bad-looking leg doing the rounds on social media not so long ago.

He is even still able to play football casually, though at 49, his appetite for the game is gradually diminishing.

It was just as I got my confidence back, I started doing a bit of fitness. Then some mates were playing on a Sunday night. I was doing non-contact with them for a year or so and then I was playing a few charity games in goal. Then it just built up and I had the confidence to go back playing.

“I came to (the age of) 35 then and there was an over-35s league, which a lot of my old non-league mates were playing in. I went and watched them, and thought: ‘I could have a go at this.’ But I’m retiring this year, because I’ve been doing it 15 years now — this is my last season.

Stan Petrov and Lee Hendrie play. And Lee Carsley and Darren Byfield play for our rivals, so it’s pretty competitive and I’ve basically just had enough.”

Busst did his coaching badges and had originally hoped to become a manager at the highest level. He even spent six years managing non-league teams, taking charge of first Solihull Borough and later Evesham United in the early-to-mid 00s, while also spending time coaching in Coventry’s academy.

Ultimately, however, a lack of opportunities prompted Busst to discard any hopes of managing full-time. Instead, he chose to focus more intensively on his role as Football Community manager at Coventry City.

I had to make a decision: ‘Where do I see my future?’ And this is what I’m doing now. In football, managers can get sacked after a month. This job, I’ve been doing it 20 years now. The security side of it is good and it’s the variation and the way the job has evolved. No day’s ever the same and variety keeps me occupied. I made that decision about 10 years ago — I was going to put everything into this and it is where I saw my future and that’s what did.

“I’m a coach educator as well. I’m an affiliated tutor for the FA. I coach the coaching courses for the FA Level 1s and Level 2s… I dip in and out of coaching the Level 1 coaches, who are coming through at the moment — that’s very fulfilling.

“You don’t have that matchday feeling. You’re never going to replicate it. I had it for six years in non-league and it was absolutely brilliant. I still manage an over-35s team on a Sunday. It’s not quite the same level but there’s still responsibility for the team, the formation, the substitutes, which will never change no matter what level you’re at. So it’s a nice balance at the moment.”

Life after football can be notoriously difficult. As The Secret Footballer noted in an interview with The42 back in 2015: “Remember the stats for former footballers — one in three will get divorced, one in three will suffer a mental illness and one in three will be declared bankrupt.”

Yet as Busst points out, for every sad case, there are many other positive stories of footballers thriving after retirement, which naturally do not attract the same level of attention.

So, as unfortunate and sad as the sudden and premature end to his professional football career was, figures such as Busst deserve to be celebrated for the resilience and positive attitudes they clearly possess.

The way I came into football, I’d been working before, so my plan at that time, when I came into football was: ‘This will last for about five years and then I’ll go back working again.’

“(How you handle retirement depends on) what sort of person you are, what sort of outlook you have on life, if you’ve got a dark soul. I can see why certain players turn to drink and things like that to cope with it. I can see where the pressure’s come from. I had good support around me and a strong family, it was just all there, and that’s important.

Most footballers are pretty single-minded, pretty positive, determined. People read about the ones that fall off the wagon, but you look at the thousands of players that have gone on (to lead happy lives).

“The PFA (Professional Footballers’ Association) are great. There are opportunities to re-train into whatever industries you want to go into. The support they give to the players after is there. A lot of them don’t want to access it, because it’s sort of admitting that you have a problem I suppose.

But it comes down to the individual you are. The support’s there for players to come out the other side of it definitely (with) the financial side of it, which is helpful.

“And so the majority of footballers, they don’t go the other way, they go the positive way.”

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!