IT’S BEEN AN emotional conversation. A lot of revelations. A lot of vulnerability and opening up.

And then, as we close in on the hour mark and everything ebbs to a conclusion, it veers in a completely different direction.

I had surprised Colin Lynch with a question. He surprised me with the answer and as I collected my thoughts and prepared a follow-up, he threw another curveball.

“Are you going to ask about the game show?”

“The game show? There was a game show?”

“Oh, you didn’t find that out?”

And then he tells me about Poker Face.

“It’s just me and my ultra-competitive streak,” he says.

Ant and Dec hosted it and the top prize was £1 million. Essentially, I was one question away from winning it back in 2007. I got down to the final two but I knew, for various reasons, I wasn’t going to win it so I took the money I’d earned and walked away with £74,000. That basically funded the first few years of my cycling career.”

“I’ve been on a few game shows and I’m actually filming another one later this month on the BBC but I can’t go into much detail about it. I did one that I was so terrible on that I can’t even remember what it was called and then I did another show called Tipping Point on Channel 5 and I won that too. It was ‘only’ £1300 but every little helps. I’m a wealth of useless facts until they’re actually useful.”

Finding out that Ant and Dec played crucial roles in Lynch’s Paralympic career certainly was an unexpected development, though delving into his stand-up past had already taken us into pretty unchartered territory.

“It was nothing to write home about,” he says, unsuccessfully attempting to brush it off.

“For a brief moment of time, I did stand-up comedy. It was back when I was living in Montreal and I was taking night classes at McGill University. Me and one of the guys in my class would go to the local comedy club afterwards for a few beers. It was always Open Mic Night when we’d go and as we’re sitting there and watching other people do their thing, I commented to him that all of them were so poor and that I could do a better job. He bet me I couldn’t and I accepted. So, I went back a few weeks later and I did a set. It was about five or six minutes but it went down really well and I kept at it for about another year.”

“I don’t think I’m a particularly funny guy. In high school, I did a lot of school plays and took public speaking classes and I was a graphic designer for 20 years so I’d have to go to corporate boardrooms and sell them on advertising concepts I’d designed. So I’ve always been comfortable standing in front of people and talking, whether on stage or in the business world. I’ve never been shy in that sense. I wouldn’t be comfortable walking into a room of strangers and striking up a conversation.”

The competitiveness. A target. With no experience but plenty of focus and commitment, he became a stand-up comic, however inexplicably. He backed himself to succeed. He sees where I’m going with it and can appreciate the comparison.

“I like a challenge and I’m a problem solver,” he says.

I tend to be very analytical and it helps in training a lot because it’s very numbers-based. You can look at the stats after a ride and see where it went wrong and formulate a plan to try and fix it. And then go out and try something based on the changes. With comedy, it’s a lot of trial and error. You write a bunch of jokes you think are funny. For me, the best comedians are like storytellers so you come up with your story. Each week you can see what works and what doesn’t. But the next week you might only change one thing. Then you keep building on it. I can see the parallels. You stick with the parts that work and you try and build on what doesn’t.”

In 2016, Lynch, who qualified to represent Ireland through his father, claimed a silver medal for Ireland in the C2 Mens Time Trial at the Paralympic Games in Rio. Before that, he’d won back-to-back golds at the UCI World Championships in 2011 and 2012. But last year was difficult. Performances were poor. He struggled to put together any kind of form. And it hurt him psychologically.

August was an eye-opener. A lonely drive back to his home in the UK from another underwhelming event in Italy. He was so embarrassed that he didn’t say goodbye to his team-mates or his coach. In the car, there was too much time to dwell on things and listen to the voices.

“I spent about two days in a car by myself driving home and that gives you a lot of time to think,” he says.

“And the things I was thinking about were not particularly positive. It was a tortuous drive. An emotional rollercoaster in terms of what I was going through in my mind. One second to the next I was trying to figure what I wanted to do, what I was going to do and wondering what everything means. It was the breaking point for me.”

Writing for InnerVoice late last year, Lynch described the journey.

“Every bridge I drove across I found myself wondering if it was high enough. That is to say: would someone actually die if they jumped from that height?”

Since that moment, he’s begun to acknowledge his depression and wider mental health struggles. And they’ve been there for a long time.

Raised in Canada from a young age, Lynch was a teenager when he injured his foot playing rugby. He didn’t think the knock was particularly bad and shunned a hospital visit. A few weeks later, there was no pain at all but Lynch was suspicious. Something just wasn’t right. During a doctor’s visit, it was found that he’d actually broken his foot and a tumour had developed on his spinal cord that had caused him to lose the feeling in both his legs. The subsequent surgery to remove the tumour was a success but a cast was then placed too tightly on his foot, which led to tissue damage and infections. The following years were punctuated by a litany of surgeries but nothing worked.

“I specifically remember the day I decided to have my leg amputated,” he says.

At the time, it was a remarkably difficult period. It was drawn out for so many years that it wasn’t just one moment in time. It was several years in time. I’d been to see a doctor and they’d said, ‘Look, we’ve done all we can and you need to seriously consider getting an amputation because if you don’t you’ll either end up dead or in a wheelchair’. My initial reaction at the time was, ‘Hell, no’ because I wasn’t ready to come to terms and deal with it. But it was several months later and I was at university. I was walking to class, through the snow and I was in so much pain. I thought, ‘I can’t go on with this, I can’t live like this’ and I made an appointment later that day to see the doctor and said, ‘Okay, let’s do it’. Once it was done and I’d decided to get on with it, it probably wasn’t that bad. I had good people around me and that made the experience less painful than it needed to be.”

“But no-one ever said it wasn’t going to be bad. All you need to do is think for a moment about what life is going to be like for an amputee. At the time, there was a certain amount of fear and not wanting to deal with what it was going to be. I did have the naivety of a teenager and I was fortunate at that age to still be in good shape so there was little recovery time and I was able to get up and move very quickly. I didn’t, at the time, have any idea of any further complications I’d have in life regarding my health. That kinda snuck up on me. But it’s probably other complications that have made my life a lot more challenging than being an amputee.”

The inevitable presumption is that Lynch’s traumatic amputation at 20 years of age sparked a darkness that has been with him ever since. But he mentions self-esteem a lot and how losing his leg contributed to the negative image he already had of himself. So where did that come from? He briefly mentions a ‘really, really crappy home life’. I ask him if he’s comfortable going into more detail about it.

“I currently don’t speak to either one of my parents,” he says.

My mother went through a series of husbands and some of them were verbally and mentally abusive to me. That’s probably what fed into this whole low self-esteem growing up. I recall one of my stepfathers just pounding into me that I was worthless and was never going to amount to anything. It was done to try and motivate me but, Christ almighty, when you’re 13 years old, you don’t think that way. You just believe what people tell you. I wasn’t particularly motivated to overcome anything I was being told so that stuck with me for a long time.”

“Later in life, I realised the negative influences I had and I just thought, Screw it’ and decided to remove them from my life. My parents had basically split when I was too young to even remember so I didn’t really meet my birth father until I was about 30 years old. We met a few times and that’s how I ended up back in England from Canada. He got in touch about 15 years ago and asked if I’d come back to England and live with him. So I agreed and I showed up and it turned out he was an alcoholic and in a really, really bad place in his life. Six months later he pissed off to Ireland and left me on my own. And that was the end of that experiment. I don’t really want to blame anything in my life on that anymore. I’ve come to terms with it and moved on from it. It shaped me for a long time but I’d like to think that because I identified it and dealt with it that it’s no longer an issue.”

It’s hard for Lynch to look at his family situation and not feel anger, bitterness or resentment, especially considering the level of trauma and suffering he’s had to go through regarding the amputation and the fallout from it.

“It would have been nice to have had a strong and supportive family unit around me all my life because it definitely would have made a difference in so many ways,” he says.

“I look at my girlfriend now and her parents live about a mile away and she sees them everyday and I see what difference that kind of upbringing can make to a person’s life. I wish I had it but I didn’t. And I still don’t. But I try and feed off of her and her family, like surrogate positive influences, almost.”

Lynch admits that he’s not a stereotypical paralympic athlete. The ‘inspiration’ tag is not one he wears easily. It’s uncomfortable. But he can see how much of his own stuff is wrapped up in that.

“Because of my own personal insecurities and negative body image or whatever, I’m really uncomfortable in my own skin,” he says.

“I’m not comfortable with my disabilities and I’m not particularly comfortable with putting them out there for the world to see. But, that’s the price of admission. If I want to be a world-class paralympic athlete, you have to get over it. I do like that my performances inspire other disabled people to get out and do something with their lives, whether in sport or in their everyday, and in that sense I’m proud to be an inspiration. But I don’t necessarily want an able-bodied person to look at me and go, ‘Well, if that guy can do X, Y, Z then I should be able to do this’. I think that’s where the whole Paralympic thing can fall down. And I think that’s why some Paralympic athletes don’t like that label of ‘inspirational’. We’re not circus freaks there for your entertainment. But, on the other hand, any sportsperson should serve, or has the ability to serve, as an inspiration to another peer group.”

Because 2018 was so difficult for him, there have been various practicalities to consider. The financial side is a harsh reality and always a fine line. When things are good, it’s great. But after a bump in the road, funding becomes an issue, even if you’re a former Paralympic champion. And as his performances suffered throughout last year, the stress and anxiety of a substantial income drop was another relentless burden.

“On the one hand, we get a lot of support from government funding and that kind of thing,” Lynch says.

“But the problem is that’s generally the only avenue of funding. If you’re an able-bodied athlete, your ability to make money from your sport is infinitely greater, depending on what your sport is, obviously. From simply being paid to do your sport to the marketing and advertising opportunities…We get one shot at putting in a decent performance every year and the following year can be based on one race, almost. If it doesn’t go well, you can kinda be outta luck.”

But, Lynch is keen to point out that he’s currently in a good place and ready for what’s next. In different ways, he’s getting back to basics and made sacrifices. Essentially, having to cut corners for the season ahead has been liberating. He’s not particularly keen dwelling on the past and that’s one of the reasons why he’s put his 2016 Paralympic silver medal on eBay.

“I put it up for sale not genuinely expecting to sell it,” he says.

I didn’t think I’d find anyone who’d pay a decent enough amount for me to sell it. However, if somebody had, I would have just done it. It was more important to me to carry on and finish the job I had started than it was to have a piece of metal that’s going to sit in a box in a cupboard and be brought out, at best, once a year. I know people don’t get it. I know people are freaked out by the idea of it. ‘How could you possibly sell this wonderful thing that you have and that you earned?’ But the accomplishment is no less because I don’t have the chunk of metal. I have a beautiful framed certificate and my race numbers from Rio are up on the wall in my training room and that’s as much motivation to me than a medal I almost never see. I also put it up for sale in the hope that it might spark a conversation, y’know? I wanted people to realise how serious I am about the sport and carrying on cycling. I wasn’t asking people for money to go off on a holiday. It was about showing people how much I was prepared to sacrifice. I thought it might help people understand how much it means to me.”

The aim is the World Championships in March and Lynch is enthused by his training and the enforced changes to his regime. It helps that he lives 30 minutes from the Manchester Velodrome and that means he’s back riding track. Instead of heading to a training camp in Spain, he’s stayed at home. The approach is different. The mentality is different. The coach is different.

“I’ve been able to dial into what’s important and get rid of anything superfluous,” he says.

“It’s the first year I’ve ever done this. And it’s paying off. I’m finding I’m back to the best I’ve ever been, at least with my track stuff. I have another few months until the World Championships so I’m ahead of the curve, for a change. In a way, everything that’s happened has probably helped me focus a bit.”

Naturally, given his personality and his various idiosyncrasies, there is some doubt. But having backed himself and spoken up and revealed the extent of his suffering, he can also acknowledge the positives it affords him.

“I was at a low point then (August) but I’m not anymore,” he says.

“It’s a gradual process and I’ve worked really hard to get out there, make all those changes in terms of what I wanted to focus on and put a plan in place to get my best results back. The hard work has paid off. There’s still room for improvement but there’s also lots of time.”

The only thing that worries me right now is the next time I have another really bad performance. Everything can go great and I can go to the World Championships in March and I can fall flat on my face again and I’m gonna be right back to where I started. And I’ve got to be prepared for that. Now that I’ve spoken up, it’s helped clue in people around me. Whether it’s coaching staff or people from the federation or even my girlfriend. I never really talked about this stuff with her. You don’t want to show weakness or necessarily tell people how bad you’re feeling. But now those people are aware of what’s going on. They won’t treat me any differently but if I am having a bad day, they’ll know I might need some more help. And if things do go catastrophically wrong, they’re probably going to be there straightaway to support me. I’m not going to have to say anything because they’ll be there already.”

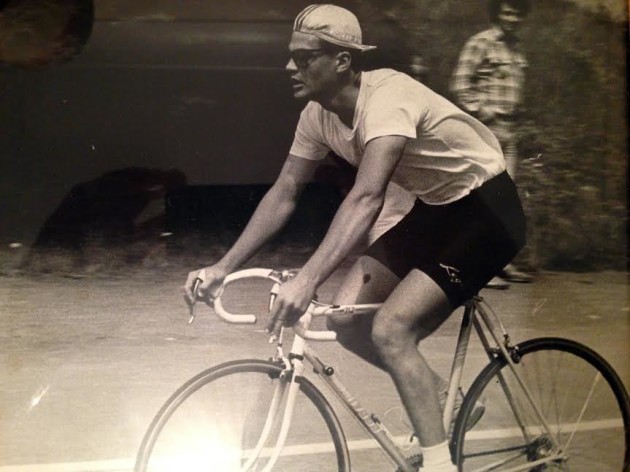

When Lynch watched the 2008 Paralympic Games and how successful the Team GB cycling team was, it was an epiphany. He’d enjoyed the bike when he was younger but had only recently fallen back into it in a quest to lose weight and get fit. Now, as he stared at the TV screen, there was a new goal. He wanted it. In a way, he needed it too. And like the stand-up comedy in Montreal and the TV game shows in the UK, the competitive spirit got him to a certain level and talent took care of the rest.

“I wouldn’t say I chose it because it’s a solitary sport. I chose it because I like doing it,” he says.

“What do I think about? It varies. It depends on where I am and what I’m doing. Half the time you’re thinking about the work you have to do in the moment. Track is short and painful so you’re just literally thinking about getting through it. You try and not think about the pain. It’s about the mechanics. Some days you’re out there and your mind can wander a lot. If something is bothering me, I’ll go over it in my head. And that’s not a good thing. You can talk yourself into a very unhappy state. If things are going well, you think about happier things.”

“When you ride a bike for your job like I do, you don’t get those days very often. You’re constantly thinking about numbers and how long until four hours are up. I have to almost plan a route that takes me far enough away from home because a lot of the time you just want to turn around and go back. If you’re too close to home, it’s too easy to say, ‘Screw it, I’ll make up for it the next day.”

Normally, my favourite time to be on the bike is the week or two after the World Championships. I’m not training, I’ve normally done a good race. I’m happy. I’m stress-free. You can ride the bike for enjoyment. You can go out for half an hour or five hours. You don’t have to hit any power numbers. There’s no structure whatsoever. Pure, unadulterated joy of riding a bike with no stress whatsoever. It’s very freeing when you ride a bike for enjoyment. I like the freedom of being out and about. When the weather is nice and you’re out in the hills and you’ve got all of nature around you, I find it very liberating and I get a buzz from that. It makes me feel really good. When I’m out on a bike, a lot of my troubles melt away.”

Lynch is grateful for the impact elite sport has had on his life. It’s changed so much for him. But he admits that the nature of it – the inevitable disappointments and setbacks – is hard to handle. He’s unable to let things slide completely and move on quickly, though he’s trying to get better.

“It wears you down,” he says.

“I’m very lucky to have put sport back in my life to at least give me a chance to raise myself above my struggles. But it’s a double-edged sword. On one hand, sport is a very uplifting experience. But when you become good at it and put all these extra demands on yourself and don’t meet those self-imposed expectations, it’s very easy to get down on yourself. And if you’re in any way susceptible to depression or mood swings, it can be very hard to handle.”

There’s one other thing that wears him down too. The constant physical pain.

“Some days I can’t sleep at night,” he says.

“It can be 4 or 5 in the morning and I’m still tossing and turning. That wrecks me for the next day and compromises everything. It means if I do train then it’s going to be compromised and I have to decide. Don’t train and try and catch up on sleep or go out, even for a crappy cycle, just so I’m doing something? Then you’re chasing your tail and trying to catch up. It could be once a week or once every two weeks when it’s just a shocker.”

Then there are the days when you just feel down. It’s hard to find the motivation when you just don’t want to do anything. I hope those days don’t happen as often as they could.”

Need help? Support is available:

Samaritans 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.ie

Aware 1800 80 48 48 (depression, anxiety)

Pieta House 1800 247 247 or email mary@pieta.ie (suicide, self-harm)

Teen-Line Ireland 1800 833 634 (for ages 13 to 19)

Childline 1800 66 66 66 (for under 18s)

A list of HSE and HSE-funded services can be found here.

Subscribe to our new podcast, Heineken Rugby Weekly on The42, here: