25 YEARS AGO, an obituary appeared in a number of UK newspapers.

“Duncan Hamilton epitomised men who merit the description ‘larger than life’, for he was one who not only went out to meet it, but who embraced it heartily at every opportunity,” said The Independent.

According to The Observer, he was ‘one of the most extrovert and devil-may-care racing drivers of the post-war era’.

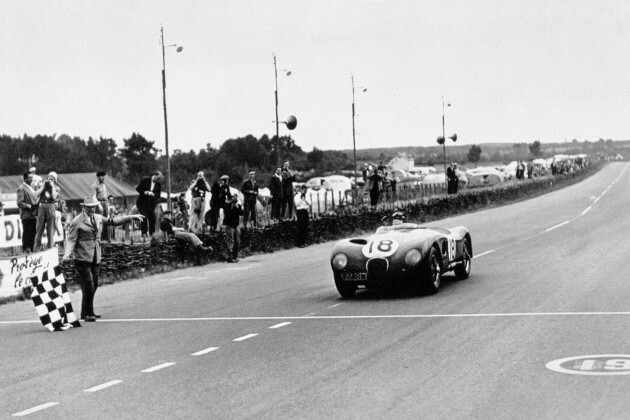

Hamilton was best-known for excelling in the golden age of motorsport in the 1950s and for pulling off a sensational victory in the iconic Le Mans 24-hour race in 1953 as part of the Jaguar team.

But nothing appeared in the Irish press about Hamilton’s death, despite the fact that he was from Cork.

Hamilton’s autobiography, Touch Wood, was originally published in 1960 and is a remarkable collection of uproarious anecdotes that shines an enthusiastic light on an effortlessly stylish and romantic era in motorsport history.

He briefly discusses his formative years in Ireland, where he was born in 1920, though the descriptions are short on detail, including his parents’ names and background. But he does make a point of recounting his father’s talents as a sportsman and how he represented Ireland in golf and tennis.

The family home was a converted monastery and was a target during and after the War of Independence. According to Hamilton, a friend of his father’s was shot at the front door and ‘more than once bullets splattered into the rooms’. He paints vivid pictures of the family sleeping on mattresses beneath the windows ‘to avoid the snipers’ bullets’.

“He was quite a busy chap, one way or the other,” his son, Adrian, tells The42.

“He didn’t talk about Ireland much and I’m not sure why his parents even ended up in Cork because they weren’t really Irish, I don’t think.”

The family moved to England when Hamilton was six and following school, he joined the Air Force when World War II broke out. In his early days learning to fly, he’d look for some final words of encouragement from his superiors.

“Remember,” they’d warn him.

“This is a valuable aircraft. We can always get more pilots but aircraft are scarce.”

Given the tutorials were clearly focused on protecting machine more than man, Hamilton inevitably crashed and was banished. Eventually, he was enlisted in the Fleet Arm of the Navy and narrowly escaped death when his ship was bombed by the Germans. He’d been drinking onboard when the explosion hit and later, as he bobbed in the freezing Nordic waters aboard a lifeboat for 12 hours, he could do nothing else other than dissect the incident and the immediate aftermath.

“This was my first real taste of war, and I remember thinking how strange it was that one man could just walk out of the bar and into a lifeboat, whereas others perished,” he later wrote.

It did not make sense to me then, for I was young enough to seek logic even in war.”

Hamilton was luckless and the vessel that rescued him and his shipmates was later blasted to smithereens by another German shell. The boat went under in 30 minutes and he was back in the water, though rescued again shortly after. But, it wasn’t long before he found himself a lot closer to an explosion and Hamilton ended up in a hospital bed for five months recovering from another German bomb attack.

For the remainder of the war, Hamilton found himself immersed in genuine espionage, particularly secret missions. He returned to the skies and would rendezvous with various European-based allied agents. There were many near misses and various colleagues who perished, but Hamilton seemed to relish the adrenaline rush.

Still, by the time the war ended in 1945, both of his parents were dead and he found the period to be lonely and isolating. His girlfriend, Angela, had agreed to marry him but only if he gave up flying and so he began searching for a desk job. And, instead of some tedious nine-to-five, Hamilton managed to rekindle a special relationship with cars.

It was back in Cork that his father used to plant him in the passenger seat and explain the different mechanics – the steering wheel, the brakes, the gears. And it fascinated him. Later, in England, he studied at the Aeronautical College and had stripped down an old Austin Seven and rebuilt it to use himself. He started to sneak into Brooklands to watch motor racing events and would even don some overalls to pose as a mechanic and get close to the vehicles. It enabled him to continue working on cars and gain some invaluable experience.

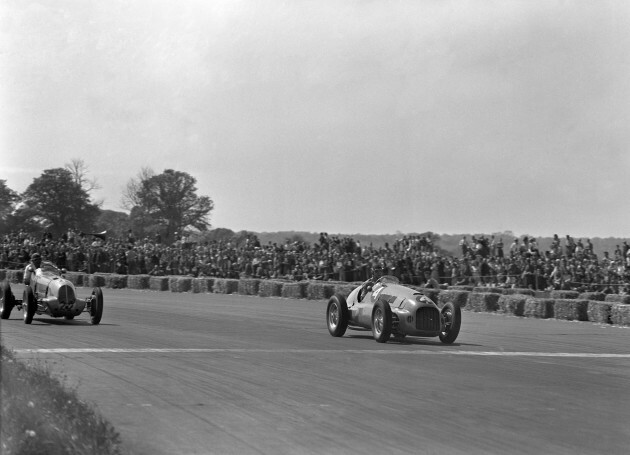

By the late-1940s, Hamilton was hill-climbing and sprinting in a Bugatti and an MG and really got a taste. Then came entering his cars in official trials and race events and he was becoming widely known on the circuit. By 1951, he was competing at the British Grand Prix at Silverstone with legendary contemporaries like Alfa Romeo’s Juan Manuel Fangio.

But, in a lifetime of spectacular stories, it’s Hamilton’s incredible performance at Le Mans that stands out.

“Those days – 1950s motor-racing – were just terrific,” Adrian says.

“Of course, they had all just come through a heavy war but there were no safety features. They had a crash helmet, but it was a rather pathetic device. There were no seat belts. The cars were built incredibly badly and they were jolly lucky to even survive. Of course, a lot of them didn’t. It was as simple as that.”

Le Mans, the arduous, relentless, gruelling show of will and determination, has existed since 1923 and is an illustrious date in motorsport’s calendar. Hamilton and his co-driver Tony Rolt had entered a number of times and even finished fourth in 1951. But in 1953, it looked like they wouldn’t even get a chance to take part.

The story goes that the night before the race was due to begin, the pair were drowning their sorrows in a local watering hole after being disqualified during practice. The drinking continued well into the morning until suddenly, six hours prior to the start, word filtered through that Jaguar had paid a fine to the organisers and the duo were back in the race. A few pots of coffee (and some hair of the dog) later and the boys were unwittingly on their way to an inexplicable victory.

Of course – paraphrasing John Ford – when there’s a choice between the legend and the truth, always print the legend.

“To be absolutely honest, the story is wrong,” Adrian clarifies.

“It all happened 24 hours earlier. The old man always reckoned he’d won courtesy of Martell and having the odd nip but you couldn’t do that job when you were half-pissed or had a massive hangover. Not even him. It all happened on the Thursday night and they were all a bit sombre because they’d been disqualified. Two cars with the same number had been on the track at the same time so the organisers kicked out number 18, which was Tony and my old man. Then William Lyons, the owner of Jaguar, went to the organisers and paid 50 francs or whatever and they were back in the race. Lyons found them in a boozer in the middle of bloody Le Mans hammering away and they certainly had to sharpen up the following morning. But it was Saturday when the race started.”

Now, he was far from teetotal, I can tell you. He was a thirsty boy. I drove with him many, many times when he was many sheets to the wind and his judgement wasn’t impaired one little bit. It was dead accurate, even still.”

Three world driving champions entered, including Fangio (Alfa Romeo), Alberto Ascari and Giuseppe Farina (both Ferrari) but none of them even finished. Hamilton and Rolt finished ahead of another Jaguar, driven by Stirling Moss and Peter Walker.

“1953 was a pretty momentous year for everybody in England,” Adrian says.

“There was the coronation of the Queen, Edmund Hillary climbed Everest, Roger Bannister broke the four-minute mile and the old man won Le Mans. And it was the first time it was won at an average speed of more than 100 miles per hour. It was an average of 105 mph. Now, you could try to do that today and you’d even be hard-pressed. One of the major features of his Jaguar C-type was that the disc brakes were so good. The Ferraris were faster down the strait at Le Mans but at the end, you have a hard right-hander and you’ve got to start braking way, way back. But with Jaguar, you could keep cruising and brake very, very late. It meant they built up a huge gap. As far as the family was concerned, it was just another race and then it was onto the next one.”

After Le Mans, he went to Portugal to drive the C-type down in Oporto and he got pushed off, hit a telegraph pole and ended up in hospital with a broken leg and fractured neck and all sorts of bloody drama. But there was no electricity in the hospital because he’d knocked down the electrical pylon down so that interrupted the supply.”

In his book, Hamilton describes how he was flung from the car and into a tree, where he ‘hung for a moment, fourteen feet up before falling onto the side of the road.’

Then, he recounts his memories of a rather unique surgical procedure.

The next thing I was consciously aware was looking up at my nude reflection in the chromium-plated light above an operating table. I could see that my chest had been ripped open and that my face was a mess. An enormous man with a shaved head stop eyeing me as he contentedly puffed at a cigar. I was about to dismiss him as an interested bystander when I saw to my horror that he was wearing a butcher’s apron and carried what looked like a carving knife in his left hand.”

Hamilton asked for water but was told it was contaminated so port would have to do. Then, the doctor began to go to work, effectively in darkness.

Fortified with port, I could just about stand the pain, but not the thought of the ash on his cigar – which was fully two inches long – falling into my open chest. I was told afterwards that he was sorry he could not give me an anaesthetic, but the anaesthetists had the afternoon off to watch a motor race.”

Hamilton managed to return to Le Mans the following year where he and Rolt narrowly finished second to Ferrari. They were within two miles of victory after Hamilton excelled following a deluge, something he was particularly adept at. But, in the dry, the Jaguar D-type just couldn’t make up the time.

It was a dangerous time for motor racing and the 1955 Le Mans event remains the most devastating incident in the history of the sport. Pierre Levegh collided with Lance Macklin and was killed instantly. Pieces of debris flew into the crowd and 83 spectators lots their lives that day.

Watching from the pit, Hamilton later wrote:

“The dead and dying were everywhere; the cries of pain, anguish, and despair screamed catastrophe. I stood as if in a dream, too horrified to even think.”

After a heavy shunt at the Le Mans race in 1958 and the death of his close friend Mike Hawthorn (who had been heavily involved in the ’55 incident) the following year, Hamilton stepped away from racing at the end of the decade.

He did remain involved in motorsport until retirement in the early 1970s and Adrian is now in charge of the family car business.

“They were terrific years, they were iron men, they got on with the job and they had a lot of fun doing it at the same time,” Adrian says.

“My father was a rumbustious character – a big, burly man and great fellow. He was a very funny and amusing guy. Everybody loved him. He loved people and always had time for people. He died 25 years ago and we still miss him. They don’t make them in the same way these days.”

Subscribe to our new podcast, The42 Rugby Weekly, here: