“IT’S BASIC STUFF, but it’s basics done to perfection.”

Sean O’Brien may have missed Ireland’s 2014 Six Nations success, but he knows as well as anyone what Joe Schmidt’s coaching is based on.

“That’s what he’s aiming for, to do everything well for every minute of every game. That’s where other coaches might not be on to you all the time – about your detail and where you’re meant to be and what your job is.”

While Ireland clearly didn’t get everything perfect in every phase of all five games, they have certainly improved as a team under Schmidt. Their championship success was deserved as they pipped England as the most impressive team in the competition.

That goal of perfecting the basics is an ongoing process for Ireland, but this Six Nations has given Irish supporters many reasons to be optimistic about the future. In this two-part analysis, we examine some of the areas in which Schmidt’s men impressed.

Obviously, there are countless details and aspects of the game that go into creating a winning team, and this is by no means claiming to be a definitive study of those. We would invite readers to contribute their own thoughts on how Ireland secured their first title since 2009.

The vast majority of the examples used here are from the win over France last weekend, but the intention is for them to reflect traits that were common throughout Ireland’s play over the course of the five games.

Scrum

It’s hard for any team to play without a set-piece platform, and Ireland performed very well throughout the Six Nations at the scrum. Solid performances over Scotland and Wales at scrum time were followed by dominance against England and Italy, and then another strong outing against France until the closing minutes.

In years past, Ireland’s scrum has looked to simply cope under opposition pressure, but this season Greg Feek has tasked the pack with being more aggressive and going after teams in a more ruthless manner.

The new scrum directives have certainly helped Cian Healy, Rory Best and Mike Ross [who initially appeared to struggle] to become more effective scrummagers. Indeed, Healy is enjoying a growing reputation as the premier loosehead in world rugby.

The removal of the ‘hit’, whereby the front rows previously had a wider gap to smash into each other on engagement, has aided Ireland’s progress, as Ross admits.

“I think the rule changes have made it different, because before it was a lottery if you won the hit or not. Some teams were really good at that, Wales were really good at that hit last year.”

The ‘hit’ favoured heavier props, even if they were technically weaker than their direct opponent, simply because their mass allowed them to win the hit and leave the lighter props unable to get back into a strong position.

The reduction of the impact on engagement has allowed props like Cian Healy [112kg, 6ft 1ins and possessing phenomenal squatting power] to get into a better position from which to drive after the ball is fed into the scrum.

Lessening the hit has also led to the players behind the props becoming of far more importance to the drive at scrum time. Brian O’Driscoll revealed that Ireland operate under a ‘scrum first’ mentality, with the flankers included in those demands.

It’s not just a tight five thing, it’s an all-eight scrummaging unit,” said the outside centre.

With far less of a ‘hit’ in which to generate their scrummaging power, props have become facilitators for the power behind them. The front row obviously remains vital to what happens at the scrum, but the locks have risen in importance.

In that regard, Paul O’Connell and Devin Toner have been central to Ireland’s scrum improvements. At around 112kg, O’Connell may not be the heaviest of tighthead locks [the player who scrummages behind the tighthead prop], but his power is in no doubt, as Ross explains.

“This year it was more about the whole eight and if you have Paulie behind you… the man gives 110% every single scrum. We’ve developed quite a good relationship and I think it’s a unit thing.

“If you look at our scrums, all eight are down and pushing hard. That’s often the difference; all it takes is one flanker to pop his head up and suddenly you get the nudge on.”

Toner may not be the most aesthetically pleasing of players, but at around 125kg, his bulk at the scrum is hugely beneficial. He can look awkward in other movements around the pitch, but the scrum provides him with more of a guaranteed plane of movement, allowing him to transfer his weight effectively in a repeated manner.

Finally, Ireland’s progress here has been underpinned by an attitude of winning each and every scrum. As with the other elements of their play we will look at in this piece, the foundation is mindset.

Ross outlines exactly how much Feek has asked of his men at scrum time. For all the technical, weight-based, refereeing, ground condition and power aspects of scrummaging, winning the battle mentally is of most importance for Ireland.

“We’ve been putting a big focus on staying in the fight, which just means you take the pressure until you think your head is about to burst, and it’s put us in good stead.”

Line-out

Ireland’s line-out performed superbly during this Six Nations under the direction of forwards coach John Plumtree and called largely by O’Connell [although Dan Tuohy and Toner filled in ably at other times].

Irish line-out stats on their own throw fell below 90% only once [86.7% against Scotland] and they managed to disrupt the opposition far more than vice versa.

The improvement on this area from 2013 – when Rory Best’s throwing was singled out – was vast, but also highlighted how unfair [or at least too singular] the criticism of the hooker was.

This season, Ireland have had three leading jumpers in Toner, O’Connell and Peter O’Mahony to throw to. Jamie Heaslip was a further option, as was Chris Henry at a push. Alongside that, all five of the above are good lifters, while Healy and Ross are excellent at getting jumpers in the air.

What it meant was that Ireland had multiple options to throw to, making it difficult for the opposition to compete aggressively in the air. On top of that, the movement on the ground by Ireland was effective without being overly complicated.

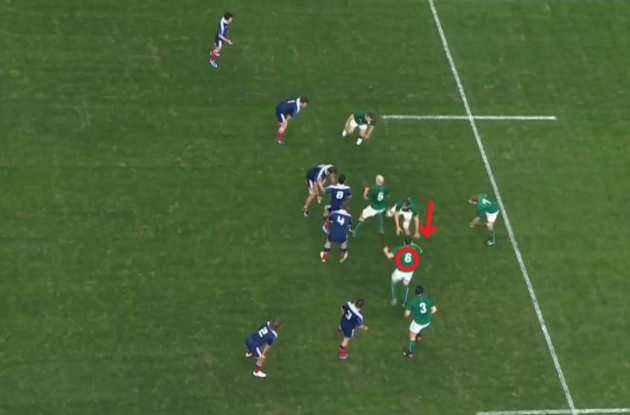

The example above is a shortened five-man line-out, but provides us with an illustration of all the aspects preciously mentioned. As we can see in the screengrab below, there are three clear jumping options as Ireland set-up for the line-out, in Toner, O’Connell and O’Mahony [each circled].

At either end of the set-up are Healy and Ross, who offer lifting options at the very front and very back of the formation. All three of Toner, O’Connell and O’Mahony are also viable lifters, so there is plenty for France to think about.

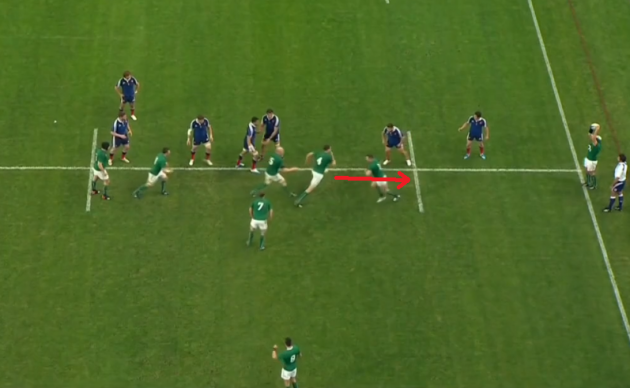

In the shot above, the situation is simplified, with Damien Chouly marked up on O’Connell, ever so slightly in front of him and ready to compete for a steal in the air. However, Ireland’s subsequent movement on the deck makes the situation altogether more favourable for them.

Toner initiates the movement, as we see above, slipping behind O’Connell as if to set up for a lift on O’Mahony [circled] at the back of the line-out. It’s a dummy movement, but crucially the French buy it for a split second and take a step backwards in reaction.

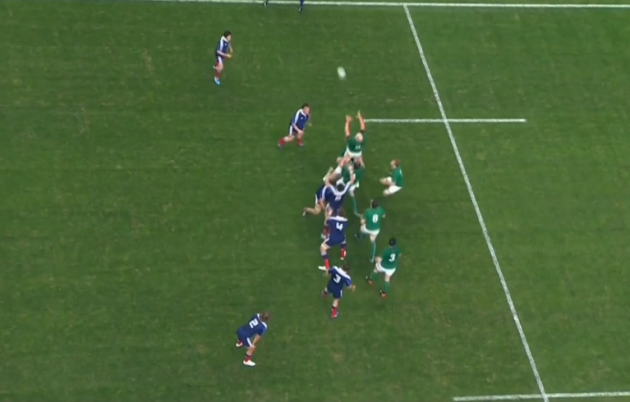

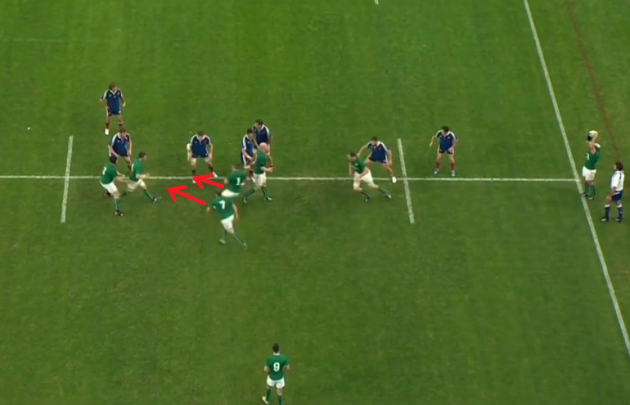

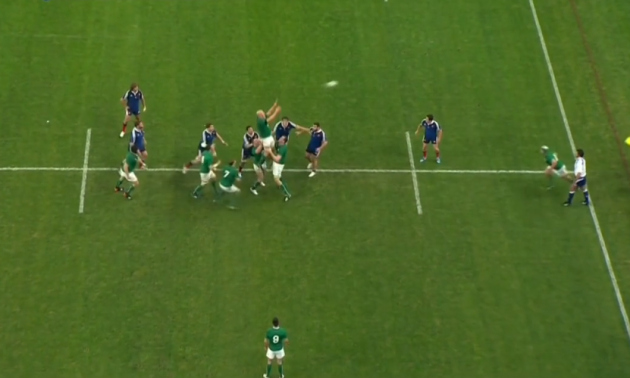

As France are taking that step backwards, Toner turns forward and lifts O’Connell. At the front of the Ireland captain, Healy has moved into position for his lift and the combination results in O’Connell getting up for a beautifully clean take in front of Chouly.

It’s a really simple passage of rugby, almost not even worth highlighting because it’s something every team does. But rather than focusing entirely on the play itself, the intention is to highlight what Ireland’s line-out did more generally in the championship.

There are multiple options, the movement is excellent, the lifting is timed superbly and Best’s throw is on the money. Basic skills carried out to a tee and with real focus; the line-out exemplifies what Joe Schmidt’s Ireland were about in the Six Nations.

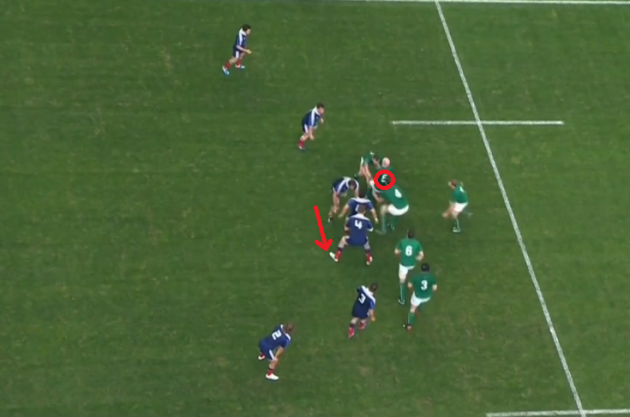

The clip below shows us a very similar example, and actually draws the penalty that allows Ireland to go 22-13 up against France in the 52nd minute.

This time Ireland sell a forward movement first, with Toner rushing to the front of the line-out [below].

Healy and Chris Henry’s movement to the tail of the line-out then draws the French into a backwards step [below].

Finally, the jump from O’Connell takes place in the middle of the line-out [below], with Toner lifting at the front and Healy in behind. Again, it’s as clean a line-out take as you’ll come across and France concede a penalty as they try to get back into a dominant position on the deck.

Both of these examples are shortened line-outs, where Ireland have positioned one of their forwards out in the back-line [Heaslip both times here] and Henry as the scrum-half, but the same principles applied to so much of their strong line-out work in this championship.

As well as allowing them to play off the top at key times, the success of Ireland’s line-out also meant they were in strong shape to set up mauls.

Maul

Plumtree has explicitly outlined his intention to make Ireland a powerful mauling side from the very moment he took control of Schmidt’s forwards. More than 14 years living in South Africa will leave a rugby coach with that inclination, and it’s been of benefit to Ireland.

We saw against Scotland and Wales how far Ireland have come, with superb maul tries against both those teams. Again, those scores were about roles being carried out in expert detail, with each of the forwards understanding exactly what was expected of them.

The try against Wales is shown above, and Ireland’s organisation is immediately apparent. There is efficient movement in the line-out to allow Toner to make a catch in front of the Welsh competition in Alun-Wyn Jones and Best’s short throw is accurate.

The transfer from Toner to Henry is one of the keys to the success of Ireland’s maul in this instance [and many others], as the second row is ‘sacked’ as soon as his feet hit the ground.

That shifting of the focal point is something we highlighted in the aftermath of the Scotland clash.

While Wales are busy sacking Toner in one direction, the Irish maul has already set up to drive off to the right, where Wales have fewer bodies defensively. Heaslip’s contribution in pre-binding on Mike Ross as the prop lifts Toner is essential in allowing Ireland to do so.

In the shot below, you can see Heaslip [wearing the headband] moving into that position early, having played his part in the line-out movement that results in Toner making a clean catch.

By binding onto the outside of Ross, rather than waiting for Toner to land and then driving the second row forward, Heaslip is facilitating that shift of direction for Ireland. The No. 8 becomes the spearhead of the ‘new’ maul, as Ross holds in Richard Hibbard to remove another Welsh body.

The shot below shows us just how early Heaslip gets into his binding position on the outside of Ross [that's his back at the bottom of the pic], before the transfer of the ball has even been carried out.

Each of the Irish players knows their roles in detail and it’s extremely hard for Wales to stop. Again, the underlying mindset is key here. Toner has outlined how Ireland “want to get excited about the maul. That’s the main thing we were talking about.”

In the latter stages of the tournament, there were suggestions that Ireland needed to pursue the maul as a continued means of beating teams up front. The fact that they came up against England, Italy and France – all three have solid maul defences – meant they felt wouldn’t make as many gains in this area.

Instead, Ireland often looked to use the maul as something of a grand decoy. The English, Italians and French were almost certainly expecting Ireland to go to the maul and take them on there.

Schmidt and Plumtree had the intelligence and humility to understand that that focus could allow them to make gains in other places. Against, England we saw examples whereby Ireland set up for a maul and then manufactured the space for a cross-field kick.

There were also two instance like that below, where Rory Best actually threw the ball right over the back of the line-out as the English anticipated a maul effort.

There were slightly similar tactics against the French, as Ireland used the maul as an attacking decoy, a way of drawing the defending team’s focus and allowing gains to be made in a different area.

We get a strong example of that in the clip below, as Ireland get into a position from where most people – apparently including the French – would expect them to pull out that powerful maul.

Henry acts as the linking player, sending a pass to Conor Murray ‘on the peel’ around the back of the dummy maul. As we see above, the scrum-half makes great yardage with a typically willing carry.

The above is actually the opening phase of the build-up to Jonny Sexton’s first try, and the use of the maul as a brief decoy allows Ireland onto the front foot inside the French 22 immediately.

We see a very similar ploy again below, although Heaslip loses his collision with Rabah Slimani after initially getting over the gainline. While the camera angles don’t allow us to see the line-out movement, it’s worth noting the starting positions of the Ireland forwards [at 0.07 seconds] and where they end up for the catch [at 0.15 seconds].

The main point is that French are probably expecting to have to defend a mauling effort just outside their own 22, but Ireland break away to create an opening elsewhere.

This was a repeated feature of Ireland’s play in the final three games, and to take it to a deeper level, we could say that Schmidt and Plumtree played a long-term dummy by mauling so aggressively against Scotland and Wales.

Both those teams were tactically susceptible to being beaten at the maul, and the impression created by those mauling performances meant the three other opponents would have been concerned by Ireland’s strength in this area.

In the words of Plumtree himself, the threat of a strong Irish maul “keeps the defence honest”.

Breakdown

Some of the enduring images of Ireland’s Six Nations triumph will involve Peter O’Mahony emerging from rucks red-faced and panting, but with the ball clutched in his hands after a superb jackal turnover.

Schmidt’s men competed superbly on the deck throughout the tournament, and much of that was down to the sheer quality of the breakdown specialists in their squad.

O’Mahony and O’Connell led the way, but the likes of Best, O’Driscoll, Heaslip, Gordon D’Arcy, Healy, Henry and Toner all played important parts too. The former pair may have won the high-profile turnover penalties, but the supporting cast consistently looked to slow down opposition ball.

The GIF above gives us an example of Ireland coming close to a steal on the ground against France, something made all the more difficult thanks to Steve Walsh’s habit of giving the attacking team the benefit of the doubt on the deck.

O’Mahony, as has become trademark, pounces into the jackal position over the ball following an excellent O’Driscoll hit on Yoann Huget. He gets his hands on the pill and actually momentarily wins the turnover, before some aggressive rucking by Thomas Domingo saves the situation for France.

It may not be a steal, but it does mean scrappier, slower ball for France as they look threatening in attack. That competition from Ireland on the ground was a constant throughout the competition, with Rory Best particularly troublesome for the opposition.

Of course there were the glamorous turnovers too, the majority of which led to penalties as the ball carrier refused to release.

O’Connell gives us a prime example of that above, snapping down over the ball and forcing Walsh to ping the French for holding on. The Ireland captain’s body position and core strength are superb as he resists the attempts of Pascal Papé to clear him off the ball.

Also of note is O’Connell’s movement just before the turnover. The second row drops back out of the defensive line as soon as the ball has passed him; he’s anticipating the breakdown before it even materialises, his eyes focused entirely on the ball.

It’s a marriage of technical excellence and sheer determination on O’Connell’s part, something that was shared among the team at the breakdown in defence. Again, the point here is to highlight commonalities of Ireland’s play in the Six Nations.

The actual turnovers are obviously more memorable, but arguably the examples like O’Mahony’s unsuccessful competition were equally as important to Ireland. Without that fight at the breakdown, the likes of France, England and Wales would have punished Schmidt’s men with quick attacking ball.

The choke tackle lives

This Irish team had many strengths for Schmidt to build on when he arrived as head coach, none more so than the famous choke tackle. Irish teams have become synonymous with turning contact situations into turnovers, and this season’s Six Nations saw that fine tradition upheld.

There was a prime example in the 37th minute of the clash at Stade de France, as Ireland turned a strong kick chase into a choke tackle. We will look at that kick chase in more depth in part two of this analysis, but here we are focused on the choke.

Dave Kearney and Best are the players to initiate the turnover, wrapping up Huget and crucially getting their arms in underneath the ball, making it difficult for the winger to drop to the floor.

Choke tackle specialist Toner gets his long, enveloping arms in on the ball too, just before Papé has the chance to rip it clear. We then see D’Arcy and Henry engaging, ensuring that there is little chance of the ball to coming back on the French side.

The choke tackle has been Les Kiss’ baby since he was appointed defence coach in 2008, and the Australian has done much excellent work in other areas too. It was fitting that the championship ended with the fruits of his labour as Ireland choked out the French in the final seconds.

Henry and Toner are then ones to initiate the tackle on Sébastien Vahaamahina this time, taking advantage of his upright carry to get in underneath the ball. We see O’Connell again onto the same page in a flash, reading the situation wonderfully well.

Iain Henderson, Sean Cronin and Martin Moore – all substitutes [an area of Ireland's game we'll look at in more depth in part two] – flood in too, wrapping their bodies around the outside of the contact zone and ensuring that the ball has no chance of coming out.

At this stage, we need hardly point out the combination of technical skill, awareness and the ‘fight’ of the Irish players to win this specific battle.

The O’Connell factor

Any examination of how Ireland improved so clearly on their 2013 Six Nations displays must include mention of the fact that O’Connell was missing for last year’s competition. The Munster lock’s importance to Ireland is hard to overestimate.

As we have seen above, he is excellent in the scrum, at the line-out and in breakdown situations, not to forget his tackling, restart ability and rucking in attack. O’Connell’s work rate is consistently high, as we will touch upon again in the second part of this analysis.

Those are the skills that are evident in the 34-year-old’s physical contributions for Ireland; O’Connell is a world-class second row who has been enjoying some of his best form in recent years this season.

Just as important are the mental contributions the Limerick man makes to the Ireland set-up. Listening in to Walsh’s mic during the France game, O’Connell’s constant encouragement to team mates was apparent.

He was slapping backs, pulling people up off the ground and constantly roaring things like “Well done, Bestie” and “Outstanding, Rossie.” On top of that, he was quietly and calmly influencing Walsh, particularly around the scrum in the first half, when Ireland won three penalties in that area.

Dealing with referees is no easy feat, but O’Connell manages those situations comfortably and more often than not builds a good rapport in a short space of time.

His work off the field is equally as tireless, with his thirst for video analysis of opposition line-outs still unquenchable. The extra work O’Connell puts in away from set training times is infectious, mirroring the hard work of the Irish coaching staff.