HE COULD ONLY laugh when he heard the abuse from the Rangers supporters. As a black professional footballer in the 1990s, it wasn’t the first time that Mark Rutherford was subjected to a form of bigotry.

But being labelled Irish scum and a Catholic bastard? This was new territory for an Englishman who was born to Jamaican parents in Birmingham.

“You could see the hatred in their faces,” Rutherford says, reflecting on Shelbourne’s two-legged Uefa Cup tie against the Glasgow side in July 1998. “It was a very hostile atmosphere. They must have assumed I was Irish. They were shouting all sorts of stuff, but it wasn’t about colour.”

In spite of the vitriolic taunts he and his Shelbourne team-mates were forced to contend with, and the fact that the outcome wasn’t the upset they were hoping for, those clashes with Rangers stand out among the highlights for Rutherford during a career which saw him become one of the most decorated players in the history of the League of Ireland.

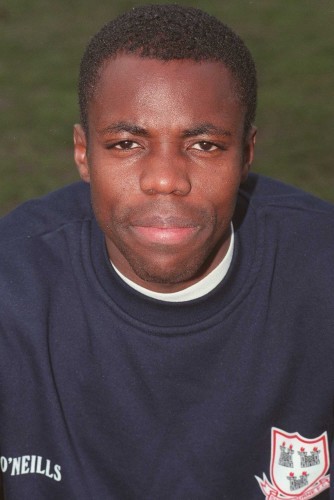

For the best part of two decades, the sight of him darting along the touchline and beyond despairing defenders was as familiar to supporters of the domestic game as Felix Healy’s moustache or Pat Dolan’s waistcoats.

Whether he was in the red and white of Shelbourne and St Patrick’s Athletic, the black and red of Bohemians and Longford Town, or the green and white of Shamrock Rovers, Rutherford was one of the most recognisable figures in Irish football.

During the 90s in particular, reasons to feel that the League of Ireland was cool were few and far between. But Rutherford, a black winger with pace and trickery who had played in England, was certainly one. Adored by his own clubs’ supporters and coveted by fans of rivals, it was only opposing right-backs who weren’t so keen on him.

When he joined an extended England squad ahead of the U18 European Championships in 1990, however, spending 13 years of his professional career in Ireland wasn’t what Mark Rutherford was aspiring to.

After he was handed his first-team debut at Birmingham City by Dave Mackay at the age of 17, Rutherford was given the chance to stake a claim at international level. The old Third Division in England was a tough place for a young winger to gain a football education, but he was making progress nevertheless.

When England’s best U18 players assembled at Lilleshall ahead of the tournament in Hungary, Rutherford played on the left wing in a trial match. Steve McManaman was on the right, Andy Cole and Chris Sutton up front. Rutherford did enough to be placed on reserve, but ultimately he never featured in the 22-man squad.

The 1990/91 season was his second in the first team at Birmingham, a club he had been with since he was an 11-year-old in the academy alongside the likes of Lee Sharpe.

Despite having undergone surgery on an ankle injury, he attracted the interest of Eoin Hand at Huddersfield Town in the summer of 1991. The former Republic of Ireland manager wanted him to prove his fitness first, which is how Rutherford was introduced to a man he says was akin to a father to him during his time in Ireland.

“Eoin Hand knew that I wasn’t fit yet after coming back from the injury,” Rutherford recalls. “He wanted to get me fit before signing me so he got in touch with Shels to see if they’d take me for a while. That’s how I ended up in Ireland.”

Shelbourne manager Pat Byrne had been in the market for someone to play wide on the left as they began the 1991/92 season. But it was Ollie Byrne, the club’s roguish owner, who ensured that Rutherford settled into an unfamiliar environment.

“I stood out when I first came over to Dublin. I had this bright blue and yellow Birmingham City tracksuit on, and people in Ireland weren’t used to seeing a black person then either. People were asking me where I was from, expecting it to be somewhere exotic, so they were a bit shocked and almost disappointed when I told them Birmingham,” Rutherford laughs.

He lived in Tallaght in the home of a couple who were friends of Ollie Byrne’s. The weekly wage, if Rutherford’s recollection is accurate, was somewhere in the region of £200 — decent money in those days and better than what was on offer for him in England. A winning goal against Sligo Rovers on his debut immediately got the Shelbourne fans on his side.

“Ollie made me feel really comfortable straight away. He always looked after me, which is probably why I stayed. I was only meant to stay for one month. Then that became two months, three months and I was enjoying myself so much that I preferred to stay, even though there were opportunities to go back to England. Ollie used to fly me back to Birmingham every two weeks, which made it easier for me to settle.

“The players were brilliant to me as well. We always went out together at the weekends. I’d be the only black person in the nightclub so I was a bit like a celebrity. People would be touching my face, touching my skin. Obviously it’s a lot different now, but back then no one in Ireland had really seen a black person before.

“I used to get the bus into town from Tallaght and all the kids on the bus would be just staring at me. But overall people were so friendly and welcoming to me. I didn’t get a huge amount of racism, to be honest; no more than there was in England anyway.”

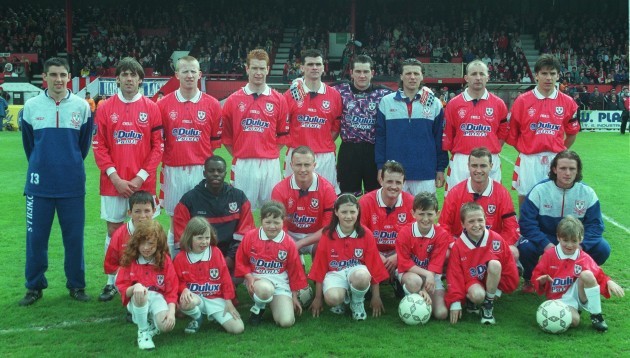

A team that contained players such as Jody Byrne, Mick Neville, Bobby Browne and Greg Costello clinched Shelbourne’s first Premier Divison title in 30 years in Rutherford’s first season at Tolka Park. A year later they ended another wait of three decades, this time in the FAI Cup.

Although it had been a satisfying first two years in Dublin for Rutherford, he still kept his eye on what options were open to him back in England. He was wanted by Shrewsbury Town, who were managed then by Fred Davies, his former youth team coach at Birmingham. Shels agreed to a season-long loan deal so Rutherford went back to live in the family home for a year while he helped Shrewsbury to win Division Three.

The Shropshire club did their best to keep him but Shelbourne’s desire to ensure that he returned to Dublin was reflected in the difference between the offers from the two clubs.

During his second spell in Drumcondra, Rutherford played in four consecutive FAI Cup finals, winning two. Despite losing to Cork City after a replay in the ’98 decider, Shels qualified for Europe again after finishing second to St Patrick’s Athletic in the league.

Rangers also found themselves in that season’s Uefa Cup, having been denied a 10th consecutive Scottish Premier Division title by Celtic. The draw for the first qualifying round saw Shels paired with a Rangers side that contained Gennaro Gattuso, Giovanni Van Bronckhorst and Lorenzo Amoruso.

Shelbourne were at home in the first leg, although any advantage was sacrificed when the game was moved across the Irish Sea to Prenton Park, the home of Tranmere Rovers, due to security fears.

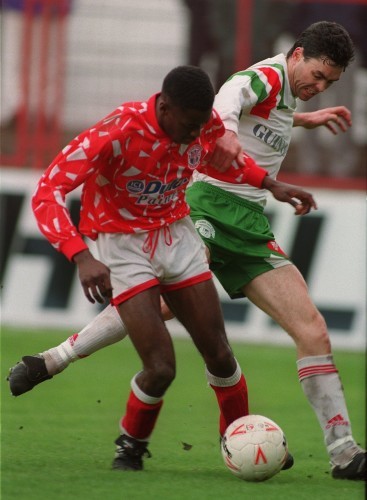

Vastly outnumbered in the stands, the 600 Shels supporters who travelled from Ireland were glad they did so after just seven minutes of the game, when an own goal from Sergio Porrini put the Dublin side in front. Three minutes prior to half-time, Rutherford fired home a second. Their lead increased just before the hour mark thanks to Pat Morley.

Shelbourne weren’t expected to offer much resistance against a side who had just forked out £5.5million to bring in Andrei Kanchelskis, yet here they were in a commanding lead.

“Everyone was thinking the same thing,” says Rutherford. “It was well into the second half and we kept looking up at the scoreboard, almost in disbelief. We started thinking about what a famous victory it would have been — 3-0 against Rangers!

“We probably should have changed our formation at that stage. We kept two up front and we kept trying to go forward. We should have sat back. But that was probably our inexperience of playing at such a high standard and in such a big game. Things went from bad to worse then.”

Defeating Rangers so comprehensively in Europe seemed too good to be true for Shelbourne, and ultimately it was. When Jorg Albertz pulled one back from the penalty spot a minute after Morley’s goal, Shels were unable to stem the tide.

Gabriel Amato came off the bench to score twice, Van Bronckhorst was also on target and Albertz added another penalty to send Rangers back to Glasgow with a 5-3 lead. Seven days later, Shelbourne’s team bus entered Ibrox for the second leg under a hail of missiles.

Rutherford: “When we were going into the ground, that reception alone kind of put us on edge. The bus was being bottled and all their supporters were shouting abuse. We were wondering what was actually going to happen when we got onto the pitch. But we switched on as soon as the game started.”

Shels gave another good account of themselves but they were unable to avoid being eliminated from the Uefa Cup. Jonathan Johansson scored twice to give the Scots a 2-0 win on the night. However, falling short against Rangers wasn’t the most disappointing aspect of that episode for Rutherford. Just before the first leg, new manager Dermot Keely — who had replaced Damien Richardson — told him he didn’t have a future with the club.

“That really came out of the blue,” Rutherford says. “Dermot said he was bringing in James Keddy instead. He told me he thought I’d been there too long and that I was starting to get too comfortable. Ollie was nearly in tears in his office when I was leaving.”

Keely’s decision to discard Rutherford came in spite of the fact that he could have ended up playing against Gabriel Batistuta and Davor Suker at the World Cup a few weeks earlier. After qualifying for the tournament for the first time, Jamaica sought to strengthen their squad by combing Europe for eligible players. Ollie Byrne informed them of Rutherford’s availability and manager Rene Simoes put him on standby, but that was as close as he got.

Rutherford had remained curious about playing in England again so his unscheduled departure from Tolka Park allowed him to scratch that itch: “It was always in the back of my head to get back to England. Lower division clubs would enquire about me but it never suited me to go back until then.”

He returned to Shrewsbury for a year. Again they wanted to retain him, but Rutherford had other considerations at that point. The Cork woman he married grew homesick so they were back on Irish soil in 1999, but north of the border this time.

Rutherford signed for Newry Town, where the standard of football wasn’t quite as high as what he had become accustomed to: ”I used to get loads of bad tackles up there because I was pretty quick and the defenders I was playing against weren’t,” he says. “I ended up having to get an operation for a knee injury. I had to wear a big strap on my knee when I got back.”

In his second season with Newry, the club experienced financial difficulties and needed to offload its assets. Rutherford was in demand. Bohemians manager Roddy Collins was among the suitors who turned up.

“Alfie Wyle was the manager at Newry. Before one of the games, I remember Alfie said to me: ‘Mark, take that thing off your knee! There’s people here watching you. We need to sell you and they’ll think you’re injured if you’re wearing that’. I went down to join Bohemians and it was the best period of my career.”

As part of a Bohs side that’s regarded as one of the greatest ever to play in the League of Ireland, Rutherford won two Premier Division titles and an FAI Cup during a three-year spell at Dalymount Park.

Then came a stint with Shamrock Rovers. Drogheda United were spending money and they offered Rutherford plenty of it, but he favoured a move to the more illustrious Hoops.

After Rovers were relegated in 2005, he completed the set of playing for Dublin’s big four clubs by joining St Patrick’s Athletic for a year. From there he went to Longford Town, with whom he reached his eighth and final FAI Cup decider, which was won by Cork City. That was 2007, a year Ollie Byrne spent battling illness. That August, Rutherford visited him in hospital.

“I went up to see him a couple of days before he died,” Rutherford recalls. “He could just about speak to me, but he was still able to talk about Shelbourne. He kept saying: ‘Are you going to play for Shels again? Go back and play for Shels one more time’. And I did.”

Rutherford spent 2008, his final season in the League of Ireland, back at Tolka Park, in spite of Dermot Keely’s return to the helm as manager. He was 36, yet supporters still voted Rutherford their Player of the Year.

Having been demoted two seasons earlier following financial problems, Shels went into the final day of the ’08 campaign knowing that a win at home to Limerick 37 would seal the First Division title and promotion back to the top flight.

Dundalk trailed Shels by a point, and even though the Lilywhites ran out 6-1 winners away to Kildare County, that result looked set to be irrelevant as the game at Tolka Park entered stoppage time with the home side leading 1-0 courtesy of Anto Flood.

“We were looking good for the win and Dermot took me off with about 10 minutes to go, thinking that we had done enough,” Rutherford explains. “Then a couple of minutes into injury time Limerick scored and Dundalk were promoted. I was sitting there thinking, I could have stopped that if I was still on! I was gutted.

“But Dermot was actually brilliant to me that season. It changed totally from when he let me go 10 years earlier. We got on very well. He was a lot more chilled. I have to give him credit for that.”

Although he had a chance to stay in the League of Ireland, Rutherford decided to bow out at the club where it all began. Wexford Youths offered him a deal but the commute didn’t appeal to him at that stage of his life. The irony of a 37-year-old playing for a team called Youths wasn’t lost on him either.

Instead, Rutherford dropped down to the Leinster Senior League to join Dublin Bus. A decent standard of football nevertheless, as evidenced by the team’s run in the early stages of the 2010 FAI Cup. After a 4-1 first-round win against Cobh Ramblers, they were drawn away to Donegal side Fanad United next.

Rutherford: “We travelled up the night before to stay in a hotel but I couldn’t get any sleep because there was loads of noise down the hall. When I left the room to see what was going on, all the players were on the piss. They had joined in with a wedding in the hotel. The night before the club’s biggest game ever and they were up drinking until 3am.”

Furious and disillusioned with his team-mates’ approach, Rutherford refused to play the game and travelled back to Dublin in the morning. When he arrived home, he found out that Dublin Bus had reached the third round of the FAI Cup after a 2-1 win. Their opponents? Shelbourne at Tolka Park.

The door was left open for Rutherford to return and face his former club, but he didn’t go back. From there he joined his local side, Lucan United, and — with the exception of a season at Cherry Orchard — it’s where he’s still playing now at the age of 44.

Due to his commitments as a coach with Lucan’s underage teams, Rutherford doesn’t play every game for the Leinster Senior League team. If there’s a clash, the kids come first — including his own. His 13-year-old twin girls are developing into promising players, their six-year-old sister is also making progress, and their four-year-old brother will soon get his chance to join in too.

When Rutherford does lace up the boots, the pace is still there. He has looked after himself over the years, and continues to do so. His lunch break at work is usually designated for a 5km run. The day job is at International Financial Data Services in Parkwest, a role he secured after earning a degree in software systems and computers.

“I’m nearly 45 now but I’m still gliding past lads who are 21 or 22. It’s funny,” he laughs. “Guys half my age will point and say: ‘Watch him, he’s got pace!’ I’ll take it every game as it comes, but I’m still feeling good.”

Football may not have brought him the sort of financial rewards that his colleagues in the England U18 squad went on to enjoy, but Mark Rutherford has a different barometer for wealth.

“I never became a millionaire but the most important thing for me was that I always enjoyed my football wherever I played. I got to play in Europe and win a lot of trophies. I’m married to a great woman. I’ve got four children.

“Am I happy with what I’ve got? How could I not be?”