Updated at 14.49

PAT MORLEY HAS stories to tell.

Athletes, and particularly footballers, often get a reputation for being media wary and cliché prone in interviews.

And while there is some truth to these negative stereotypes, Morley is the antithesis to them.

The gregarious Cork City legend may be best known for his phenomenal goal-scoring ability, but he is a natural raconteur to boot.

The interview starts later than originally planned, as he is busy at work. I assure him it “shouldn’t take more than 20 minutes”. Over two anecdote-filled hours later, the conversation comes to an end.

1. Like father, like son

The tales are diverse, from being hailed as a top striker “from Yugoslavia” during a stint in Australia to a trip to Munich that encompassed both Oktoberfest and one of the most unforgettable performances from an Irish team in recent memory.

The stories have one common denominator, however. They all, ultimately, can be traced back to his late father, Jackie, and his own deep love of the game.

A League of Ireland legend in his own right, Jackie Morley was a former Cork Hibernians and Waterford player.

In 1967, Jackie was signed by none other than Martin Ferguson — brother of the legendary Manchester United manager, Alex. While at Wateford, he won four league titles, including three in a row between 1967 and 1970.

Morley Senior, who played for West Ham between 1958 and 1961 before coming home for family reasons, also took part in a number of memorable European Cup matches against sides of the calibre of Manchester United, Celtic and Galatasary, scoring a memorable goal against the latter at Lansdowne Road in 1969.

The pair are not the only athletes in the family either — Pat’s mother Joan played camogie for Cork, as did his sister Sheenagh, while his brother Dave also enjoyed a stint in the League of Ireland.

“I used to go down and see my dad when Waterford won the league in ’72 in Flower Lodge, which is now Páirc Uí Rinn,” Morley tells The42.

“I was in the crowd with my mother at that. I saw them come back from 2-0 down to win 3-2 against Cork Hibs. My dad was an ex-Hibs man, but he was let go by Hibs to go down to Waterford.”

Unsurprisingly given this proud tradition in his family, Morley excelled in more than one sport growing up. He played hurling “at quite a high level” and also represented Munster in tennis.

Soccer, however, was Morley’s first love. He started out playing right-back at Norton Celtic. One day, he was put up front and proceeded to score eight goals. “They said ‘maybe you’re a centre-forward,’” he recalls.

2. Glasgow calling

From there, he represented Cork Youths and Wilton United. While with the latter, he was spotted by a Celtic scout who just happened to be visiting family in Ireland.

“He was just walking his dog on the same day in Carrigaline that I scored a hat-trick. He sort of said ‘we need to get you over to Celtic.’”

An underage coach at Wilton, Pat Bowdren, played a big role in a young Morley’s development, as did his late father.

All dads are great, but mine was a gentleman,” he says. “He never pushed me. Himself and my uncle, another man who passed away as well, Jim Clancy, they used to travel to all the games with me, but they were never very critical.

“They would ask you what could you have ‘done better’. They’d never tell you. But that’s the way my dad was. I’d sort of work on things with him.

“I lived on the streets playing football, we’d throw jumpers down, we’d be playing at the gates, I broke so many windows of other people’s houses. If I missed a goal, it was a broken window.

“There was all that type of stuff going on, but my dad would never come out and play with us. My dad would take me out the back garden and try other things. When we’d go on summer holidays, we’d be down in Tramore, because my father would be doing pre-season with Waterford down the sand dunes.

“I would never say I was naturally talented, because I did work very hard at shooting practice and things like that, but when I meet people now, they tell me that my father would say ‘I think he has something,’ but he’d never say that to me.”

3. Memory lane

Along with the many highs, there were also some lows in Jackie’s career. The FAI Cup proved elusive, as he was a losing finalist on four occasions. When Pat was part of the Shels side that won the trophy after beating Derry in the final in 1997, he offered Jackie his medal.

“I was on the subs’ bench even though I was never going to come on — my knee was done. I had a cruciate [injury], but I didn’t know I had a cruciate. I was brought up on [to receive the trophy], because I scored all the way up to the semi-finals.

“The Shelbourne lads made a big song and dance about it, because they knew how much it meant to me. My dad was there after, so we went out to Tolka Park for the do — I gave my dad my shirt and my medal and he wouldn’t accept it. He walked out the door. I said ‘you have to have it, that’s for you’.

“I gave him my ’93 league medal, because he never won a league medal with Cork. He said ‘I don’t want it’. That was him. He was an amazing man. He’s dead five years in November, but he did so much [for me].”

4. Start as you mean to go on

Jackie was there too for his son’s League of Ireland debut with Waterford against Finn Harps in Ballybofey.

In 1984, Celtic had sent Morley to Waterford in an unofficial loan deal. After roughly six weeks in the Irish side’s reserve team, he was deemed ready for first-team action.

“My dad travelled up with me and my uncle, Jim Clancy. And [former Ireland international and Waterford manager] Alfie Hale we met in Holyrood Hotel [in Bundoran]. My dad knew [legendary Gaelic Football manager] Brian McEniff, because Brian played with Waterford under an assumed name, because of the GAA ban.

“They were talking and drinking all night and the following morning, I didn’t think I was going to be playing for Waterford the same day and Alfie Hale says to my Dad: ‘Come on, we’re going for a walk down the beach where all the surfers go.’ He said: ‘I’m starting Pat today.’

So I said ‘yeah no bother’. I went out and scored a hat-trick. [The League of Ireland's all-time leading goalscorer] Brendan Bradley was playing against me the same day. We won 4-1. I got on the bus and my dad didn’t open his mouth the whole way home. I gave him the ball. It’s still in my mother’s house today. He never spoke to me about it. But he said to my mother after: ‘I’m just so proud of him.’ But never spoke the whole way home.

“He had nothing to say. His exact words to me were: ‘How do you think you did?’ I said ‘I missed two good chances.’ He said: ‘Oh yeah.’

“The debut was 25 November, 1984 and my father died on the 25 November as well [in 2013].”

He continues: “Even when I got seen by Celtic, it’s another very funny story. Celtic were very interested at the time and they came over to see me. I was like ‘this is mad’. I was picked up at the airport, I’d never flown on a plane. I had to go over on my own because my dad couldn’t afford a flight.

“He eventually said he was going to try to get a boat over. From what I gather, he drove to Belfast and he got a boat over from there. We were playing in Parkhead against Rangers in a reserve game and my dad ended up in Dumbarton. He thought the game was in Dumbarton. How he did, I don’t know. But that was him — he drove all the way to see it.”

Morley’s time in Scotland may have been relatively brief, but there were still some memorable moments. While playing in the youth team there, he was trained by Bobby Lennox and Jimmy Johnstone who were both part of the famous ‘Lisbon Lions’ — the Celtic side that became the first British club to win the European Cup, beating Inter 2-1 in the 1967 final.

The Irish youngster even played up front in a team that included former Scotland international Alan McInally, with Morley scoring in a 5-0 defeat of Rangers amid a reserve game in front of 25,000 fans.

“What happened with Celtic, they really liked what they saw because I scored a few goals in a few matches.

“They wanted me to beef up a small bit because I was only 5’9′, 5’10. I was a bit of a wimp. I was over there with massive players, like Frank McAvennie, Roy Aitken, Packie Bonner and Paul McStay. These were huge men in my view.

“Before we’d go training, we’d do 400 sit-ups on a mat on the Celtic crest in Parkhead. I didn’t even get to 20. They were pounding out 400 and I’m gone. Then they’d make you run to the training ground — all the first team would drive and we’d run.”

5. Confidence

Despite the seemingly daunting surroundings for a 17-year-old unaccustomed to being away from home, Morley insists he never suffered from nerves before games.

“There was never a pressure on me. I never felt I had to go out and perform in my earlier days. My dad was my idol. I had enough of people screaming at me on the pitch. It was totally different times.

The one thing [my father] did for me and my brother was he brought us to Dalymount Park to see a League of Ireland team playing Santos. He said: ‘I’m going to get you into the dressing room and you need to meet someone and you need to get his autograph.’ I was saying: ‘Yeah, whatever dad, why are we going up here?’ He said: ‘No, you need to see these people playing.’ I said ‘alright, okay,’ and so we went into the dressing room and we met Pele to get his autograph.

“We didn’t have a television, so for the 1974 World Cup final, he took us to a friend’s house who had a black-and-white television. He said ‘you need to watch how these play, the Dutch’. He said you need to look at this guy, number 14, Johan Cruyff. My dad was a centre-half and he battered people, but he always spoke to me about players who had influence.

“I played up front with a guy called Martin ‘Mock’ Reid [when I was starting out]. Mock’s attitude was very funny. He said ‘right Pat, I’m playing up front today,’ because the centre forward at the time was injured. He normally played left-back. He said ‘I’m going to batter them, don’t worry about it, I’ll take care of all those, you just try to get on the end of something, will you?

“So I actually relished it. The bigger the occasion, the bigger the moment, I just loved it.”

6. Stepping up

While still a teenager, Morley won his first trophy at senior level, scoring a penalty in Waterford’s 1985 League Cup final triumph.

We got to the final against Finn Harps,” he remembers. “And they were all looking at me, going: ‘He scored?’ I had the balls to step up and take a penalty at 17, 18 years of age. They were going: ‘Huh?’ But I had no fear.”

Despite this early success in the League of Ireland, the original plan for Morley to return to Celtic never materialised.

“There was an issue about money. There should never have been an issue about money,” he says.

“In between all of that I was on trial at Brighton. But unfortunately, when I was down in Brighton, people decided to bomb the Grand Hotel. So that didn’t help.”

In the end, Limerick manager Joe O’Mahony persuaded him to join the club in 1985.

Yet the team ultimately never challenged for major honours during Morley’s stint there. It was a strong league then with Jim McLaughlin’s famous Shamrock Rovers ‘four-in-a-row’ side dominant.

After two years at Limerick and a relatively impressive goals-to-games ratio (19 in 37 matches), Morley felt the need to move on after falling out of favour with Billy Hamilton, who had replaced O’Mahony as manager, and the talented young attacker went back for a second spell at Waterford.

“That year wasn’t as good as it should have been, the country was not in a good state, so it was time to look elsewhere.”

7. The big move

With no agents to assist him back then, it was former League of Ireland players Noel King and Noel Mitten that helped arrange Morley’s subsequent move to Australian top-flight side Sunshine George Cross.

You were making nothing in work at the time,” he recalls. “I was working with Nike and earning £84 a week in a store.

“Obviously, I’d been over at Celtic for a while, but I was with families, so this was me going away on my own for the first time. And it was life-changing, because it was looking like I was never going to come back home. This was 1988 — Ireland was gone as a country. I’ll never forget it, Michael Jackson played down in Páirc Uí Chaoimh, I went to the concert. Next day, I was on a plane.

“I’ve only ever seen my father cry twice — that was when I was going on the plane and when his mother died.

“You’re going to a country that’s miles away — no mobile phones, no emails, you were 11 hours ahead. If you made a phone call, it would cost you a fortune. And I didn’t have the money.”

Morley lived in Sandringham, a beachside suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, and was impressed by the ultra-professional set-up in Australia.

It took several months before he got clearance from Waterford and the Football Association of Ireland to play for the club’s first team, so he spent the intervening period with “George Cross’ Munster Senior League [equivalent] side, which is Sandringham”.

He explains: “I was doing very well, so as soon as the clearance came through, I was brought up to the first team. It was out in a ground with 7,500 people and I scored from about 35 yards. It was one of the goals of the month or season or whatever. It came up that I was “Patsiki Morlican’ from Yugoslavia, or something like that, on the television.

“It changed things very quickly for me in Australia, because they started trying to find out who you were. There were papers like the Melbourne Age and the Melbourne Sun out there. They started chasing me. They put two and two together and they were pulling Irish shirts out, because there were no Irish people out there at the time.

“If you go onto Sunshine George Cross’ Wikipedia page and scroll to ‘famous players,’ I’m up there. Unfortunately, they’re down in the Victoria State League now. At the time, we were very good and when I came back home, the following year, they won the league.

“It stood to me because I was getting the professional set-up, even though I was still working out there. We were paid for training. If you trained, you got paid.

I was training four or five days a week out there [in contrast with] coming from League of Ireland where you just trained on a Tuesday. It wasn’t really training [in Ireland], it was just running in the shit to be honest, the pitches were horrible.

“[In Australia] we were out playing on beautiful pitches with loads of balls. You’re going up training at six o’clock at night and you’re there until 8.30. Then you go in and they’d feed you. Then you’d go home. And then you’d do the same the next night.

“I would have loved to have stayed there. I never wanted to come home. It was just an incredible place to play.”

8. Homeward bound

Family issues compelled Morley to take the plane to Ireland in what was originally meant to be a temporary return.

“I decided to go back to Australia, but then you remember the time where I saw my father crying at the airport, the mother was saying: ‘Do you really need to go back? Can you not stay home now?’”

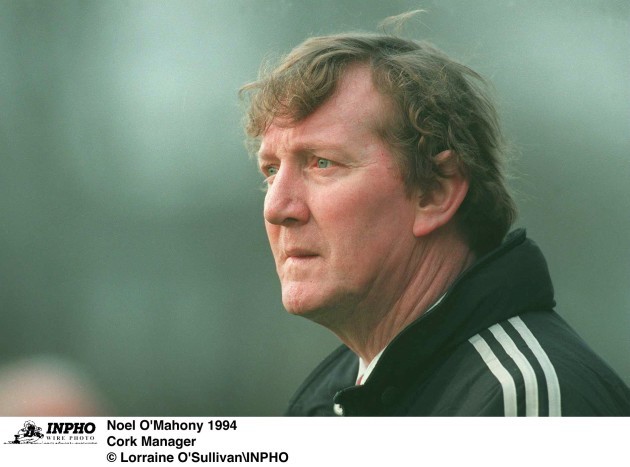

In November 1989, Morley joined Cork City, who were managed by the late Noel O’Mahony. The player’s feelings about the transfer were mixed. As proud as he was to be joining the side, it was tough to return to the League of Ireland, given the standards he had become accustomed to in Australia. His first game back, against Athlone at St Mel’s Park, was a rude awakening.

“Athlone was a huge club at the time. They had amazing results against AC Milan and it has a huge history in League of Ireland and it should be encouraged to get back up there.

“But we had a shocking bus going up to the game, it was real old Ireland: depressed, shite and awful. The Mitre ball wasn’t even pumped correctly — it wasn’t even white and it was an old one. When you went to head the ball, you’d have a migraine afterwards. Nothing had changed from the time I left Waterford two years previously.”

9. Teething troubles

Although Morley would enjoy the best spell of his career at Cork, the early days were far from promising. They finished the 1989-90 season in a solid but unspectacular fifth position.

Our training facilities at the start were in a caravan park by the airport. We used to play in a small little field in the back of a caravan site, because we weren’t allowed play in Turner’s Cross.

“There was many a morning where we’d be training and people would be throwing out stuff from the toilet or wherever out onto the pitch.

“The ball would go under the caravan and someone would have to go and get it. And that was 1989.

“We’d have to go home in the car and have a shower… Even when I came back to Cork, after I went to Shelbourne, we used to train on a Saturday morning out in Ballincollig Recreation Centre on a pitch that would have been full of glass bottles — that was 1998.

“I’m not saying it was wrong, but this is where we were as a standard of football. We’re training in the caravan park on the Saturday morning, and you’d go down on the Sunday and people are saying ‘you’re shite’ and ‘you’re not playing well’. We’re sticking up two cones that we might take from the road as goals.

The caravan park there could have had fucking horses on it the day before. People might turn around and say ‘you shouldn’t be saying things like that,’ but that’s being honest.”

Given these problems, it was all the more remarkable that Cork City ultimately became the best side in the country during Morley’s time there. The one resource they had in abundance was excellent footballers. Individuals such as Phil Harrington, Gerry McCabe, Paul Bannon and (current City manager) John Caulfield were among the integral members of the side.

They had four top-three finishes on the bounce, between 1991 and 1994, and were talented enough to win more than their sole title triumph in 1993 — not that they didn’t come close to claiming more silverware on a couple of occasions, though. They lost the 1992 FA Cup final 1-0 against Bohs, with Dave Tilson’s goal separating the sides.

“An awful lot of us didn’t play that day,” he recalls. “The whole philosophy at the time was you play how you train.

I remember we went up by train, which was unusual for us and realistically, I shouldn’t have played in the cup final, but the reality at the time was that you had one sub and no one knew you were injured.

“We just didn’t perform again on the day against Bohs and the better side won. But the day before, we had this horrendous training session. We kicked the shit out of each other.”

Cork were also pipped to league title by Dundalk in 1991. The sides faced each other on the final day at Turner’s Cross, level on points in the league, with Cork needing a victory to lift the title. It wasn’t to be, though, as Tom McNulty grabbed the winner for the Lilywhites.

“The club decided that we needed to get away from the houses, so they took us down to Innishannon Hotel the night before the Dundalk game. A couple of players didn’t have beds, because there weren’t enough beds in the hotel.

“We got stuck in traffic, we were actually late getting there. So we only got to it about 40 minutes before the game. And on the day, we didn’t perform.

“We went through games where we were just shit on the big stage. That was down to key players.”

10. Success at last

Cork finally claimed the title in 1993, despite a disastrous start to the season.

We started off at St Colman’s Park and got hammered by Bohs 4 or 5-0. We were looking at them and saying ‘we’re not going to win anything’.

“Then we had a manager who was mad — Noel was the nicest man on the earth, but mad. There were no tactics, it was just: ‘We’re going to go out, we’re going to put them under pressure, real Jack Charlton-style. Kick it up to the big man up front, kick the living daylights out of everybody and hopefully we get a result.’

“I suppose it would be the fear of losing [that motivated you], because Noel would kill you. His training was really tough. We’d go to Bishopstown and train, but we’d turn on car lights, because we had no floodlights.

“We rarely trained on the pitch, because it was a bog, it wasn’t set up correctly in the first place.”

11. The next level

For every heartbreaking loss in that era, there was often the consolation of an adventure abroad.

“When we lost the league against Dundalk, for some unknown reason, the chairman decided we were supposed to play Red Star Belgrade in Musgrave Park. But there was trouble in Belgrade, there were the riots and all that. So to look after us, we were sent to China [to compete in the Marlboro Cup].

“After drinking the whole way out there, we realised we’re playing the Chinese Olympic team in front of 55,000 people followed by the Polish team.

“At the same time we’re out there, the European Cup draw is being made, and we’re [paired with] Bayern Munich.

So what I would say to people is: ‘Yes, we lost the league to Dundalk, yes, it’s hard to take, but out of losing to Dundalk, we went to China and we played Bayern Munich.’”

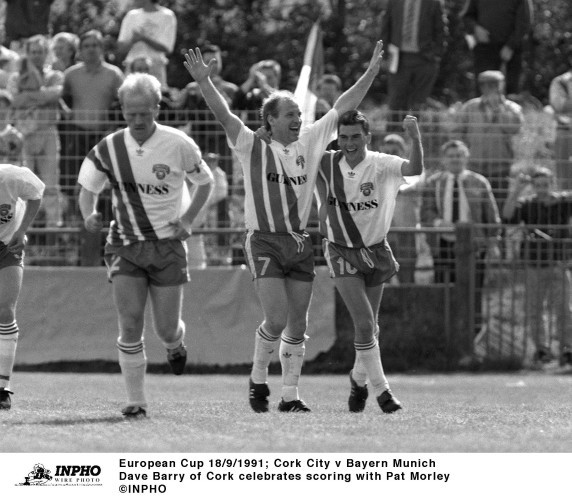

The two-legged tie against the Jupp Heynckes-managed side in the 1991-92 Uefa Cup, in particular, is an occasion Morley and his team-mates will never forget.

Dave Barry’s famous goal at Turner’s Cross helped the League of Ireland side earn a highly creditable 1-1 draw against the German giants. They battled well in the second leg too, before two late goals saw O’Mahony’s side fall to an unfortunate 3-1 aggregate loss.

12. Munich mayhem

The fact that an Irish side acquitted themselves admirably against stars such as Stefan Effenberg, Christian Ziege and Thomas Berthold was astonishing in itself, and the backstory is similarly spectacular.

“They sent over their own buses to ship the players around [for the first leg]. The game itself [at Musgrave Park] was amazing.

“I had one or two chances and still believe I was taken down for a penalty, but that’s another day’s work.

“The biggest frustration to me was we actually should have beaten them in Munich. We were good enough, we had some great chances. And they got two late goals. And it was just tiredness [that cost us].

But what you have to remember about Munich was, and people won’t believe this, when we flew out on the Sunday, we were met by [then-Germany manager] Berti Vogts at the airport in the Bayern bus. He said he was taking the directors out to the beer festival. It was the Oktoberfest that was on. We said: ‘No, we’re going.’

“So we all went to the beer festival on the Sunday night, we had loads of beer, got back to the hotel at three o’clock in the morning, we were playing on the Tuesday night. The following morning, we got up for breakfast, and Noel O’Mahony took us out and ran the living daylights out of us.

“The TV cameras came over and it was all over the newspaper there called Bild that Munich were playing ‘pissheads’ basically.

“Only for the cameras coming, Noel wouldn’t have stopped. That was Monday morning. So we stopped after three hours at about one o’clock. Then, that night, we went over to the Munich stadium and we played 8-v-8 for an hour, the full length of the pitch. So we rested Tuesday morning and played Tuesday night.

“And for 75 minutes, we had them. We had a couple of chances that we didn’t take, then they got a breakaway goal.

“And unfortunately, they got a handball [in the box] near the end. Ziege scored the penalty and they beat us 2-0.

“It’s not to say ‘if we were more professional’ because at the time, it was the right thing to do. I won’t say it was a holiday, but you have to remember, the only time Cork were in Europe before they went to Russia and got hammered [they were beaten 6-0 on aggregate by Torpedo Moscow in first round of the 1989-90 Cup Winners' Cup].

So we got Bayern Munich, who got to the semi-final of the European Cup the previous year, they had amazing players like Effenburg, and you’re going: ‘We’re going to get canned here.’

“Our attitude was ‘we’ll just go out and be blasé’ and there were a few dopey comments where they said [Cork City] were full of plumbers and all that.

“The one thing we knew we could do was kick. We were going to chase them and harry them and say everything we could to get at them. John Caulfield played outside right against a guy called Manfred Bender. And John will tell you this himself, his whole duty was just to stop him and he did, fair means or foul.

“I played up front on my own, but our whole thing was keeping the score down. When we scored, we were going ‘Jesus,’ but going out to Munich, we cherished it.

“It was back to what I said a while ago. I watched Holland play Germany in the ’74 World Cup final. I’m now playing in the stadium where my dad was showing me this great player. So I’m walking on the same ground as the likes of Franz Beckenbauer, Johan Cryuff. I watched these on telly and I’m going: ‘I’m now standing and playing on this ground?’

So I had no fear and we’re in the bath after, celebrating after losing 2-0, drinking like lunatics and then you sit back afterwards and think: ‘Christ, we could have won that. But who cares?’ We met Alan McInally and went off out on the piss. Gerry McCabe, myself and Mick Conway had the Bayern Munich gold card. We stayed in a hotel and drank till 5 in the morning. And that’s the way it was. There was no recovery or anything like that.

“If we trained better, maybe we would have given a better account of ourselves, or maybe Bayern Munich were saying: ‘These fellas have been on the piss the last two days, we only have to walk out and we’ll beat them.’”

13. Glory

Another memory that stands out was the dramatic circumstances behind Cork City’s first-ever league title triumph in 1993.

Bohemians, Shelbourne and Cork finished the season level at the top, with each team having accrued 40 points. It meant the league would be decided by a series of three-way play-offs.

We went off down to Kinsale on the beer,” he recalls. “The same night, Bohs were playing Shelbourne in Dalymount.

“So we all went out as if it was our end-of-season do, because we felt the league was over. Then, at about 10 o’clock that night — because it wasn’t televised — it came through that we were back in and there was another play-off. We were all pissed and realised we were playing the next Wednesday. So we were back in training the following morning.”

Morley finished the campaign as the league’s top scorer on 20 goals, with his side sealing their triumph amid a thrilling 3-2 victory over Shelbourne.

“Then it was just 3-2, it ended up being a chaotic game, it could have been 10-9. There were no defences and it wasn’t that the defences weren’t good. It just seemed to be one of those games where every time someone had an attack, it looked like they were going to score. I don’t know if it was ever televised, but from a television viewpoint, it would have been unbelievable.

I laugh about it, I missed the presentation. They were presenting the cup, I was out on the pitch with the supporters.”

Morley continues: “I went into the dressing room afterwards and the cup was there, and it was a shitty cup at the time, because it wasn’t the proper League of Ireland trophy that my dad had won. And there were photographs with people coming in — the Bishop of Cork came in, Jack Charlton came in and they were all talking about it. I just sat there and just said: ‘Do you know what, you’ve achieved it.’

“But I didn’t feel anything until we got back to Cork the following day, when we got off the train and we got the bus into the city. Then it sort of hit home. When you’re inside in Guinness House, we’re sticking out the window and seeing thousands of people outside, you’re going: ‘Jesus, it means something now.’”

14. Great expectations

Nevertheless, the league triumph proved to be as good as it got for that illustrious group of players. Having brought the title to Cork, O’Mahony wanted to bow out on a high and so, stepped down as manager. He was replaced by Damien Richardson, who attempted to instil a more professional set-up into the club.

They failed to retain the title in the 1993-94 season, finishing second to a Stephen Geoghegan-inspired Shamrock Rovers team. And the following campaign, disaster struck. Cork were top of the league, when Richardson had a falling out with the powers that be at the club and resigned as manager. O’Mahony returned to the hotseat, but their old manager’s presence could not provide the necessary boost they needed.

The Leesiders’ form dipped dramatically, and they finished the next two campaigns in seventh and ninth place respectively.

Cork virtually collapsing so suddenly after everything that they had achieved was heartbreaking to all concerned, especially from the perspective of someone with as deep an affinity for the club as Morley.

“There were certain things done, we can’t say what they were, but people who owned the club at the time had other agendas. My view is very simple — we had a squad of players and a manager who brought the club to where he needed to take them.

“We then brought in another manager to take us to the next level, and he did. We played in the European Cup, we had a great result against Cwmbran Town when we were dead and buried.

“And then we should have beaten Galatasaray, we had them. They were a great side. They went on the following round to knock out Man United.

“We scored out there [in Turkey], we had great chances out in Bishopstown — we should never have played out in Bishopstown, it was a fuckin’ disgrace, pissing rain. I still get slagged if I go over to Turkey about it, because it was horrible.

“The [Galatasaray] stadium was mad, it was probably one of the best experiences in my life playing out there, just an amazing atmosphere, loved every minute of it and we performed, we were good. We held them to 2-1 that night and we had chances.

“And we lost 1-0 at home to a late goal by Kubilay Türkyilmaz.

The following year, we played one of the best sides I ever played in Europe, Slavia Prague. We lost 2-0 out there and I was being interviewed by Trevor Welch of Multi-Channel at the time, he’s now with TV3. And they were doing warm-downs while we were breathing through our ass.

“We brought them back to Cork and I’ve said this to people, I’ve only been beaten really badly twice in my life. Against Slavia Prague in the second leg, they beat us 4-0 and it could have been 10. There was about eight of them on the Czech Republic team.

“The other team that absolutely hammered us was the year we won the league — pre-season, we played Leeds and they beat us 3-0.

“I’ll always remember that game, because when we were coming out the old Turner’s Cross dressing room, seven of their players had to duck their heads going through the door.

“They had Lee Chapman, John Lukic was in goal, Jesus Christ he was 6’10 and we just got battered. But in 1994, we had the attitude going out to Prague that ‘we can play these people’. And we were beaten 2-0, so that’s where we had got to.”

15. Dublin dilemma

But these wonderfully unique occasions felt like distant memories as the decade wore on, and after two tumultuous seasons of managerial disarray and little stability at Cork, Morley controversially opted to join Shelbourne in 1996.

The dire situation that the club found themselves in did not help matters, but the star’s work situation also played a big part in his decision to make the switch.

Dave Barry had taken over [as Cork manager]. Dave was obviously a good friend of mine. I just said ‘Dave, I don’t think the club is going the right way.’

“On top of that, I was now working with Adidas, which I had been since 1995, and my job spec had changed. Adidas wanted me to be in Dublin more and they wanted me in Manchester more.”

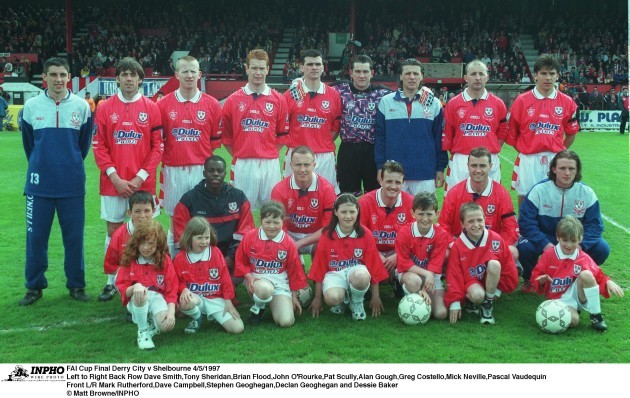

After a slow start, things started to click for Morley with the Dublin side. He formed a prolific partnership up front with Stephen Geoghegan, while a talented team also included Pat Scully, Mick Neville and Tony Sheridan among others.

A cruciate injury, however, marred Morley’s time at Shelbourne and kept him out of action for over a year.

While he did at least finally claim an FAI Cup winners’ medal after coming on as a late substitute against Derry in 1997, he could only watch on the following season, as Shels finished just a point behind champions St Pat’s in the league.

Morley did, however, return in time for an unforgettable 1998-99 Uefa Cup tie against Rangers. The Scottish team, who were managed by Dick Advocaat, featured several top players of that era, including Gennaro Gattuso, Lorenzo Amoruso and Giovanni van Bronckhorst.

Against the odds, Shels went 3-0 ahead in the first leg, with Morley scoring the third, but a similarly improbable comeback saw their opponents emerge as 5-3 victors. Despite the disappointing climax, he retains fond memories of the occasion.

“I basically was walking around the dressing room, saying: ‘We can beat these.’ Dermot Keely said: ‘Would you shut up?’”

A couple of months earlier, Morley — who was still effectively recovering from injury — made a late substitute appearance in the 1998 FAI Cup final, which Shels lost 1-0 to his former side Cork in a replay, after the original game was drawn 0-0.

“When Cork won the cup, I hugged every one of them.

“Deccie Daly, who had the cruciate beforehand, helped me, even though I was with Shelbourne. He gave me all the rehabilitation [advice] and gave me the doctor that I was to go and get my cruciate done by.

“I came on in the cup final, the first ball was played down the line, he buried me into the stand. And after we drew the first game, I brought all the Cork lads out to a nightclub in Dublin.

I’m a Cork man. I’d played with them. Yes, I was gutted [to lose]. But I was delighted for them, because they deserved it.”

16. Pain and gain

Such disappointing results had been put into perspective by what Morley had gone through previously. Having possessed seemingly unshakeable self-confidence for much of his career, the ACL setback was the first time that he began to seriously doubt himself.

“Once I did my cruciate, I was packing up. Shelbourne, in fairness to them, they brought me over to Kilmarnock [ahead of a 1997 Cup Winners' Cup tie].

“I went out onto the pitch [to train], I could kick a ball and started burying balls into the top corner.

“Damien Richardson said to me: ‘There’s nothing wrong with your knee.’ It just had sort of healed a bit.

“I roomed with the doc, Alan Byrne, and Alan Kinsella, ex-Bohemians right full-back, who was the physio. I went back into the room and they absolutely beat the living shit out of me and told me I was having the operation, because I went over to retire.

They saw me on the pitch that day and I hadn’t kicked a ball in 11 months, because I didn’t want to have [the operation]. I just got totally depressed. It was: ‘No, I’m finished with football, 30 years of age, done.’ I got on the plane, went back and had the operation the following week.

“They played Dundalk the following night, went into the hospital in Dún Laoghaire [after] and they stuck bottles of beer into the knee canister. Alan Kinsella came back and filmed the operation for a thesis.

“So that’ll tell you why I talk about these people in high esteem, because without them, I wouldn’t have come back.

“If I didn’t go to Kilmarnock, I wouldn’t have carried on. If I didn’t go to Kilmarnock, I wouldn’t have scored the goal against Rangers.”

17. The second coming

Despite this new lease of life, however, he left Shels shortly after the Rangers game. With the recently appointed manager Dermot Keely under pressure to get results and continuing doubts surrounding the player’s fitness, Morley was allowed to depart and re-join Cork.

At first, it was like old times, with the Rebels a top side again under the management of Dave Barry. In the returning striker’s first season back, the club won the League of Ireland Cup and were desperately unlucky to miss out on the title, finishing just three points behind St Pat’s.

The following season, they finished runners-up again, though Morley managed to emulate his achievement of the ’93 campaign by finishing top scorer with 20 goals.

Shels even made a move for the player again, as it became apparent he had lost none of that trademark goalscoring ability, but Cork were now a force to be reckoned with and “after doing it once and the grief I got, I couldn’t do it again”.

The Leesiders were not far off in the 2000-01 campaign either, when they came third, but the team were on the wane, as highlighted by their sixth-place finish the following season.

In 2002, Morley reluctantly hung up his boots, togging out for the last time just over a month before his 37th birthday.

“My last game in the League of Ireland, and it was lovely, was the Brandywell. Liam Coyle came up to me and said ‘well done,’ and I just said to Coyler: ‘Look, I’m done.’ He said: ‘Ah Jesus, you can’t go.’ I said: ‘Yeah, I think I’m done.’ I’ve spoken to him since and he was probably the best that I played with and against in my time in League of Ireland, because he was just genius. So for him to say something like that, you sort of say to yourself: ‘Maybe I was half-decent.’”

18. Deja vu

Morley wasn’t gone for long. In 2005, with his old boss Richardson coming back to manage Cork, the former striker returned to the club in an advisory role.

In Richardson’s first season there, Cork City emulated the class of ’93. They won the league title for the second time in the club’s history.

However, in the similar manner to their ’93 counterparts, the victory was made bittersweet by the trouble that followed, with financial issues resulting in a period of examinership.

Before the problems escalated in the late ’00s, Morley, who is now 52 and these days owns the Scribe of London brand, had stepped away from proceedings in 2007, with Richardson also departing that same year after guiding Cork to a FAI Cup triumph against Longford.

Since the examinership debacle, however, the situation has taken a considerable turn for the better, with the Leesiders winning their third league title in 2017.

Meanwhile, Morley’s legacy as a League of Ireland legend is assured. He is Cork City’s joint-all-time top goalscorer, with himself and former strike partner John Caulfield both having found the net 129 times for the club.

In the list of Irish football’s most prolific marksmen, he is third, with only Jason Byrne and Brendan Bradley having managed to score more than his overall tally of 182 goals.

A few years back, Morley sparked controversy by suggesting First Division goals should not count in this prestigious list, but he is at pains to explain the comment was not meant as a dig at any other individuals on the list.

I am totally honoured and humbled to be even mentioned in the same breath as Jason Byrne and Brendan Bradley,” he adds.

“And I was also hugely honoured — and God rest his soul — to be named in Jimmy Magee’s best all-time League of Ireland team. That shocked me.

“And as I said to Jimmy before he passed away, I would never have been in his team, only for my dad, because without him, I wouldn’t have been born. Without him, I wouldn’t have achieved what I’ve achieved, and I wouldn’t have got the grounding in soccer that I’ve got.

“I’m just honoured to be in a position where people can call me a legend, but I mean this, my dad’s a legend, not me.”