“My boxers had better food than my children. And I was happy. I swear to God this is true. I was so fanatical about boxing that I sacrificed everything. I wasn’t sleeping. I was just thinking about the boxers.”

Zaur Antia

AT FIRST GLANCE, they were an odd threesome. Gary Keegan, a Dubliner, Billy Walsh, a Wexford man and Georgian native Zaur Antia, whose English vocabulary consisted of six words when he arrived in Ireland twelve years ago. But this triumvirate changed the face of Irish amateur boxing forever.

They all come from working-class backgrounds. Born in Ballybough, in Dublin’s north inner city, Gary Keegan walked past Croke Park on his way to school every day, though like most inner city kids in the sixties he never played in the stadium.

Instead, after his family moved to Coolock, a friend, Michael Thompson – whose older brothers, Paul, Shay and Tommy were all noted pugilists – inveigled Keegan to join Transport Boxing Club, which, ironically, was based back in the inner city.

Walsh grew up in Wolfe Tone Villas, a corporation housing estate in the centre of Wexford town – within sight of the county’s premier GAA ground.

“Every family on the estate seemed to have six or seven kids and I was a robust young fella.

“The gym for St Joseph’s Boxing Club was in the grounds of the local Christian Brothers’ school. The Brothers were heavily involved in the running of the club. I discovered years later that my late father, Liam, asked them to take me into the club to calm my ways.”

Initially, Walsh had no luck. “In my first county championships I got a headbutt which left me with a closed left eye for a few days. Then when I went to the Leinster championships the eye swelled up again and I had to withdraw.”

He also dabbled successfully in Gaelic football, hurling and soccer. By the time he was fourteen, he had won an All-Ireland boxing title and was a member of the Wexford U-14 soccer, Gaelic and hurling teams. “I should have been a brain surgeon but I didn’t have time to study,” he suggests with a wry smile.

Kilkenny were not as dominant in hurling in the 1980s as they are currently. Walsh entertained realistic ambitions of winning silverware with his mates, who included Martin Storey, Tom Dempsey and John O’Connor – all of whom played pivotal roles in the county’s historic All-Ireland success in 1996.

Another of Walsh’s teammates on that U-14 team which won a Leinster title was Andy Ronan, who ran for Ireland in the Olympic marathon in Barcelona in 1992.

In the 1981 Leinster Minor Hurling Final, Wexford, the defending title holders, looked set to capture back-to-back titles for the first time since 1967–1968 when they led by five points with six minutes left. Walsh vividly remembers what happened next.

“I was playing wing back, and being marked by John McDonald from Mullinavat. I was clearing a ball, but he got a touch to it and it went out over the side line. But the linesman gave them the decision. I remember glass milk bottles were still in use at the time and a few of them were thrown at the linesman.

“From the side-line cut somebody doubled on the ball in the square and it finished up in the back of the net. Kilkenny won the match by a point. There and then I said f*** this! I threw my hurley down and vowed that I was going to box in the Olympic Games.

“I didn’t want to be relying on fourteen other fellas. I gave up hurling and football and set my sights on celebrating my twenty-first birthday in three years’ time at the Los Angeles Games.”

The eldest in a family of three, Zaur Antia was born and raised in Poti, a port city in Georgia, located on the eastern Black Sea coast.

On 14 March 1921, the city was occupied by the invading Russian army who installed a Soviet government in Georgia, which remained in place until the dissolution of the USSR in the early 1990s.

Antia’s father worked as a labourer in the thriving port. In common with the rest of the population Antia’s family spoke Georgian, one of the oldest languages in the world. There have been suggestions that Jesus prayed in the Georgian language.

“When I was growing up we were under Russian occupation but it wasn’t a big deal, though we all learned to speak their language.”

The local boxing club was housed inside the port area, a five-minute walk from his parents’ apartment. Antia went along with his friends, but he also sampled soccer and wrestling.

“I was good at wrestling, which is a very traditional Georgian sport, but my boxing coach “poisoned” me. He made me love boxing by making a motivational speech before every training session.

“He was like a father to me; he was a very special coach. He was always reading the newspapers. Once he said to me, “Zaur, listen to me – this newspaper only cost two cent. Take it and read it.”

“I did what he asked and as a result I started to read books, many books. When somebody speaks to you at a particular time in your life it can make a big difference.”

Unlike his two colleagues, Gary Keegan did not make his name inside the ring. Instead, he left home at the age of sixteen to join the merchant navy. By the time he returned three years later there was an embryonic drug problem in parts of Dublin, including Coolock.

“Drugs had just arrived in the area and concerned parents approached me to give them a hand at setting up a boxing club in order to get the kids off the streets. I set up Glin Boxing Club in the local community centre which was just across the road from where I lived.

“However, I quickly realised that I was neither qualified nor experienced enough at the age of nineteen to run a boxing club or coach the kids. I plugged into Tommy and Shay Thompson [who was Irish featherweight champion in 1982] as they had both just retired from boxing. I asked them to help out. They both came down; Shay didn’t spend too long, but Tommy became the head coach of Glin Boxing Club.’

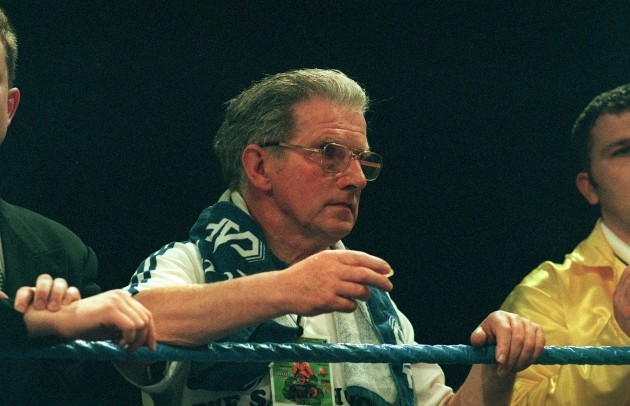

After he got married, Keegan moved to Blanchardstown. There he got involved in Corduff Boxing Club and set about acquiring his coaching badges under the tutelage of four of the legendary figures in Irish amateur boxing: Austin Carruth, Breandán Ó Conaire, Michael Hawkins and Mick Dowling.

Later, he set up a new club called St Mochta’s on the Clonsilla Road in Blanchardstown. Initially, it was based in an old national school, and when that closed they moved to the St Brigid’s Community Centre in the village and renamed the club St Brigid’s Boxing Club.

Keegan ran this club for seventeen years. Hundreds of kids passed through it, including an Irish-Jamaican youngster called Darren Sutherland. During this period Keegan also became increasingly immersed in the affairs of the Dublin County Boxing Board and the IABA.

Despite the heartbreak he endured when Wexford failed to win the Leinster minor title in 1981, Billy Walsh didn’t give up entirely on the GAA. Indeed, at times, it proved an important outlet for his talents when issues inside the ring soured his love affair with boxing.

He was a substitute on the Faythe Harriers team that won the Wexford senior hurling championship in 1981. Three years later, when he was controversially left off the Irish boxing team for the Los Angeles Olympics, he found refuge in the GAA.

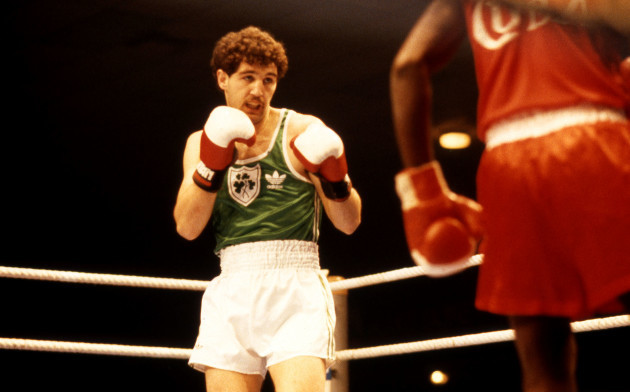

Following his defeat by Michael Carruth in a box-off for a place on the team for the Barcelona Olympics in 1992, Walsh switched to coaching. Together with Tom Hayes, he ran St Joseph’s/St Ibar’s Boxing Club, turning it into one of the top clubs in the country.

Once they had five national title holders on their books. A three-year drop in the upper-age limit meant that Walsh was ineligible to bid for a place on the Irish team to compete at the Atlanta Olympics in 1996. But a year out from the Games the age limit was restored to thirty-five. Walsh couldn’t resist the urge for one last hurrah.

“I was working for a company called Snowcream, who were part of the Glanbia group. I went to them and they agreed to sponsor me.”

Two weeks before the Elite championships, Walsh busted his hand in a club bout against his namesake Billy Walsh, who was a native of Cork and had won an Elite title at welterweight in 1994.

Then he got the worst possible draw – he was pitted against another Cork native, Michael Roche, who four years later was the only Irish boxer to qualify for the Sydney Olympics.

“There weren’t too many punches thrown, but he ended up beating me. That put it to bed once and for all. Actually, RTÉ retired me!

The late Noel Andrews, who was commentating on the fight, and Mick Dowling, his co-commentator, came into the ring afterwards and asked me such pertinent questions that I had no option but to announce my retirement on the spot. I knew I hadn’t got it any more. I cried all the way home to Wexford.

“After I retired originally in 1992, I remember my dad saying to me, “Son, you don’t come back.” And when it was all over he said, “I told you so”, and he was right. But I just felt that [Olympic] medal was in me somewhere but I never got to it. So I just went back coaching with my club.”

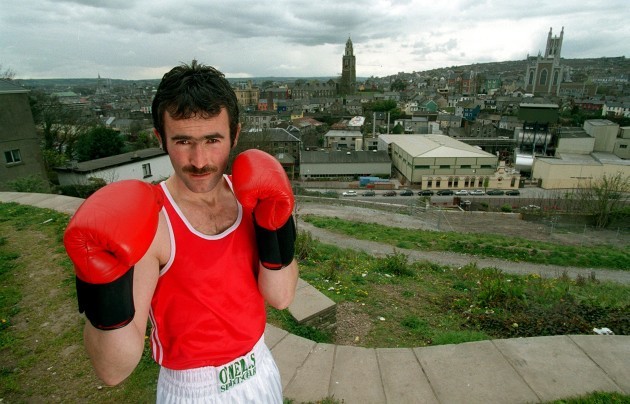

Now regarded as one of the best technical boxing coaches in the world, Zaur Antia was anything but a stylist when he donned a pair of boxing gloves.

“At the beginning I was only a bronze medallist. I was a tough fighter but had no skill. I was not thinking. I was just physically trying to win. When I was sixteen or seventeen I learned more about boxing and came to understand that it is like chess; you need to think.”

Antia won five Georgian senior titles. He represented his native city, Poti, in the Spartakiad, a mass participation sports festival held every four years in Eastern bloc countries prior to the break-up of the Soviet Union.

He qualified to compete in the Soviet Union championships – a rare achievement for any sportsperson who came from Poti – and won a bronze medal. In addition, he was awarded the title Master of Boxing by the USSR.

However, his career within the ring left him unfulfilled. “I felt I didn’t achieve enough. Of course, my dream was to get to a major championship. But I always remember what my coach, who as a boxer didn’t make it to the Olympics either, said, “Sometimes there are people whose possibility is bigger than their achievement.”

“When I boxed, Georgia was part of the Soviet Union and it was very difficult to win a Soviet title.”

The Soviet boycott of the 1984 Olympics meant that Antia would have missed out even if he qualified. But then his life took a different route. He got married when he was twenty-one; he became a father shortly afterwards when his wife, Nona, gave birth to their daughter, Natia.

Then, having completed two years’ compulsory army service, he enrolled as a student at the Institute of Sport in the Georgian capital, Tbilisi, a five-hour, 344-kilometre drive across the Likhi mountain range from his home in Poti.

He was a part-time student; he travelled to Tbilisi twice a year for five years, staying for a month attending lectures and sitting examinations. For the rest of the year he worked in Poti as an organiser of sports events and as a boxing coach. It quickly dawned on him that he had found his real vocation in life.

Back in Ireland, Gary Keegan was making progress through the labyrinthine governing structures of Irish amateur boxing. He served as vice-president of the Dublin Boxing County Board, but his abiding passion was coaching.

He got his opportunity when he became involved in the coaching committee of the Dublin Board who ran squad sessions in Dublin clubs in the aftermath of Michael Carruth’s historic gold medal win in Barcelona.

Carruth’s uncle, the late Noel Humpston – who was Kenny Egan’s first coach – and the late Paddy Hyland from Tallaght worked alongside Keegan. They crossed paths with the late Austin Carruth, then arguably the most influential coach in Irish boxing in the wake of his success in Barcelona.

“I think Austin took a bit of a shine to me and took me under his wing. I always found him a great sounding board for my coaching ideas. Our relationship grew over time, and Austin co-opted me on to the IABA’s National Coaching Committee. I was only thirty-three, which in terms of the age profile of the other members was very young.

“Dominic O’Rourke, who was the youngest coach on the committee until I arrived, was probably ten years older than me.

“I got involved in managing the structures around international squad sessions at youth, junior and senior levels. I set up the squad training programmes and put coaches in charge of them.

“This was my introduction to seeing how things were done and why Irish teams were not doing as well as expected. This got me thinking a lot about how we prepared our boxers for international tournaments.”

Keegan had first-hand experience of the preparations ahead of the Atlanta Olympics in 1996 when Ireland’s ambitions were seriously undermined by an exodus of boxers to the professional ranks.

In the wake of the Barcelona Olympics, Michael Carruth and Wayne McCullough turned pro, as did Paul Douglas and Kevin McBride. [McBride was to enjoy fifteen minutes of fame in 2005 when he beat former world heavyweight champion Mike Tyson, who quit on his stool before the start of the seventh round of an untitled fight in Washington DC.]

Worse still, seven of Ireland’s leading Atlanta hopefuls, including former European gold medallist Paul Griffin as well as Danny Ryan, Jim Webb, Darren Corbett, Mark Winters, Martin Reneghan, and Neil Sinclair also joined the pay ranks in 1996.

Sinclair had won a gold medal at the Commonwealth Games in Victoria, Canada, the previous year, as had Webb, while Winters and Reneghan both won silver.

The loss of Sinclair, who had also won medals at European and world level while a junior, cut deep within the IABA. It underlined the difficulties which the organisation faced, as its president Breandán Ó Conaire acknowledged at the time.

“It was known for some time that he [Sinclair] was unemployed, and professional managers were trying to sign him up. A bursary should have been put in place to make it financially viable for him to remain an amateur until after the Olympics at least. Now we have lost a great talent, which has weakened our Olympic hand considerably.”

Four boxers, flyweight Damaen Kelly (who had won a bronze medal at the European Championships in Denmark four months earlier, to add to the World bronze he captured in 1993), Francis ‘Francie’ Barrett, Brian Magee and Cathal O’Grady, qualified.

Most of the attention was focused on Barrett, the first member of the Travelling community to represent Ireland in the Olympic Games.

Living on a halting site at Hillside, on the eastern edge of Galway city, Barrett’s career was nurtured by barber Michael ‘Chuck’ Gillen in the Olympic Boxing Club, whose training base was a locked-up metal shipping container which had no electricity or running water.

From these humble origins Barrett made it to Atlanta. He was given the honour of carrying the tricolour and leading the Irish contingent into Centennial Olympic Park for the opening ceremony.

Inside the ring, Barrett made a winning debut in the light welterweight division, hammering Brazilian Zely Fereira dos Santos 32-7, before losing 18-6 in the second round to eventual bronze medallist Fethi Missaoui from Tunisia.

Heavyweight Cathal O’Grady was stopped in the first round by a New Zealander Garth de Silva, who exited the tournament in the next round.

Belfast natives Damaen Kelly and Brian Magee made it through to the last eight. Kelly lost 13-6 to the eventual silver medallist in the flyweight category, Bulat Jumadilov from Kazakhstan, while Magee lost 12-9 to Algerian Mohamed Bahari who won a bronze medal in the middleweight division.

Occasionally an individual Irish boxer broke the mould, as evidenced by the performance of light heavyweight Stephen Kirk at the 1997 World Championships in Budapest. He captured a bronze medal, though was stopped by the eventual champion, Russia’s Alexandr Lebziak in the semi-final. Unfortunately, on the eve of the 1998 Commonwealth Games in Kuala Lumpur, Kirk was forced to retire after failing a brain scan.

By then the world of amateur boxing had changed utterly. The former Soviet republics were now established boxing powers, and Ireland had slipped further down the ranking list. This was illustrated by the fact that for the first time ever, only one Irish boxer, Michael Roche, qualified for the Sydney Games in 2000.

Meanwhile, Gary Keegan had risen through the ranks of the IABA. He was chair of coach education and secretary of the National Coaching Committee. He had qualified as a coach tutor and was involved in developing a new coaching education programme for boxing. And he was also running his own business.

“I was doing all the boxing work on a voluntary basis. I was running a transport company, which I sold and moved into retail. Later, I went back into transport, but like all passionate sports people, whenever I was negotiating a work contract I checked out how it would impact on my involvement in sport.”

At the beginning of the new millennium, Walsh was working as a milkman in his native Wexford while continuing to coach at club level.

Twelve days into the new century, Nicolás Cruz was named as the IABA’s first ever full-time National Coaching Administrator. He was to have the support of two part-time staff – one of whom was Walsh.

Walsh was an obvious choice for the position, according to Cruz, “I used to get on very well with him and his late father Liam. He was always interested in coaching. While Billy was still boxing I remember telling him, ‘You are going to be one of the best coaches in Ireland.’”

For Walsh it was a chance in a lifetime, though taking up the job involved significant sacrifices. He was self-employed and the position of assistant coach was voluntary.

“I thought it was a great opportunity for a young coach, even though there was no pay.”

Initially, the squad prepared in Athy for the qualifiers ahead of the Sydney Olympics. Walsh remembers, “The set-up there wasn’t good enough really, so we ended up going to the University of Limerick. There were three pre-qualifying tournaments for the Sydney Olympics in March/April 2000. Nicolás [Cruz] would have gone to the tournaments while I stayed behind with the boxers who weren’t involved.”

Walsh had to turn down another opportunity to work with Cruz ahead of the European Championships in Tampere, Finland, in May 2000.

“I simply couldn’t afford it. I had to pay somebody to look after the milk round when I was involved earlier in the year.”

Nonetheless, a flame had been ignited in Walsh’s soul which ultimately yielded spectacular results.

From the moment he started coaching school children in Poti, Zaur Antia used a different approach than his contemporaries.

“There were ten of us coaching in the schools, all of whom were trained by my first boxing coach, whom I loved very much and who was very famous. But I was completely different to the others.

“When I spoke about boxing, up to fifty children came to listen and they all came back to train. None of the others, including my original coach, had fifty coming to training. During my own career I had learned that boxing is better than fighting in the ring, so I coached boxers differently.”

Eventually, there was a stand-off between Antia and his former mentor. “He called me something which wasn’t nice. I was different. I loved the way I was teaching them how to box, and I told him I would prove that I had the best approach.”

Traditionally, Georgian boxers gathered in clubs at noon every Sunday for a sparring session.

“They came to Poti because they knew that’s where they would find the best sparring. When the young boxers I trained matured and started sparring, they did well. Coaches found out that I didn’t copy; I did my own thing. I have something that I never learned from anybody.”

His protégés began to make an impact, not just in Georgia but in the Soviet Union itself. In the latter half of the 1980s Georgian boxers coached by Antia garnered medals at the Soviet Union championships.

“This is how I became involved in the Soviet Union boxing squad. Now I was working alongside their head coach Nikolay Khromov. I was spending most of my time away from home, not just in Moscow, but at different training camps.”

However, everything changed with the collapse of the old Soviet state in 1991. Antia was offered a sweetheart deal by the Russians.

“They asked me and the two Georgian boxers, Koba Gogoladze and Zurab Sarsania – who were members of the Soviet Union squad at the time – to stay in Moscow. They said, ‘If you sign a contract, we will give you a club here. You will have good money. Your boys [boxers] will stay here and we will continue to work together.’

“The boxers came to me looking for advice. But I was thinking, if I stay, my country will call me a traitor.”

Antia left Moscow and returned home to Poti with his two boxers, whom he now felt morally obliged to support.

Having declared independence on 9 April 1991, Georgia rapidly descended into chaos. Just eight months later, a bloody coup d’état sparked a civil war which lasted four years.

“It was a terrible time; there was no electricity, water or fuel. The Russians cut off everything. People weren’t being paid. There were mile-long queues for food.

“The boxers were from poor families and had nothing. I was trying to feed them in my own home, and I wasn’t thinking about my own family. All I knew was I had food in my house and I had to feed the boxers.’

Eventually, his tearful wife Nona called a halt. “She said, ‘I love when people eat with us, but we don’t have enough food – the children have nothing to eat.’ I was so fanatical about boxing that I sacrificed everything. I wasn’t sleeping. I was just thinking about the boxers.”

Antia deployed his ingenuity and friendships to see his boxers through the civil war. He persuaded the mayor of Poti to provide him with a letter urging restaurant owners to provide free meals for the boxers.

Armed with the letter, he approached restaurateurs and appealed to their patriotism. The boxers got fed. “My boxers had better food than my children. And I was happy. I swear to God this is true.”

Business acquaintances of Antia’s provided them with pocket money; a physiotherapist friend looked after their injuries, and others provided them with vitamins.

In time, normality returned to Georgia which enabled Antia to secure sponsorship for his boxing club from the company that ran Poti port. Under his guidance the club mushroomed into the biggest and most successful in the country, and Antia became head coach of the Georgian junior team.

The new independent state of Georgia made a sensational debut at the 1993 European Championships in Turkey, winning four medals. Antia coached super heavyweight Zurab Sarsania to a silver medal.

Tragically, the boxer was later murdered at the age of twenty-one. Antia’s other protégé, lightweight Koba Gogoladze, won a bronze medal at the 1997 World Championships in Budapest and a silver at the Europeans a year later, before leaving Georgia to pursue a professional career in the UK and the US.

Antia’s dream was to coach a Georgian boxer to win an Olympic title. But a disagreement with the president of the Georgian Boxing Federation and a chance encounter with an Irish boxing referee changed the course of his life and that of Irish boxing.

* Chapter 7, extract from Punching Above Their Weight: The Irish Olympic Boxing Story by Sean McGoldrick.

On sale in all good bookshops and at www.obrien.ie

http://www.obrien.ie/punching-above-their-weight