THE FOOTBALL WORLD was still reeling from The Impossible Job, the stunning documentary about Graham Taylor and what turned out to be England’s failure to qualify for the 1994 World Cup, but various teams remained fascinated by the very nature of fly-on-the-wall content.

Leyton Orient allowed a camera crew embed themselves in the club during the 1994/95 season for the purposes of a Channel 4 documentary. But, similarly to Taylor, manager John Sitton subsequently became a pariah owing to his portrayal.

When Sunderland granted access to a production team for a BBC One series called Premier Passions, which followed the side’s return to the Premier League for the 1996/97 campaign, it was boss Peter Reid who became an unwitting star.

As Rob Smyth superbly put it in The Guardian many years later:

“The variety in his management generally extended to whether he should use the word ‘fuck’, ‘shit’ or ‘bollocks’ in his half-time team talks.”

Again, the manager became the punchline and, most importantly, helped shape perceptions that became impossible to shift.

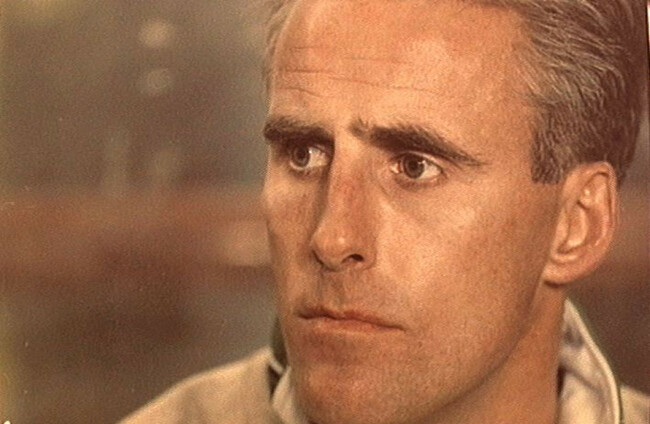

So, when newly-appointed Mick McCarthy and the FAI agreed to a proposal from fledgling company Setanta Sports to produce a documentary for RTE focusing on the Republic of Ireland’s attempts to reach the 1998 World Cup in France, it was a brave move.

The Irish team was in transition. It was the embers of the Charlton era. Veteran players were still crucial but everything needed refreshing. By the time the side were preparing for the first qualifier against Liechtenstein, the Euro ’96 play-off defeat to the Netherlands remained an unshakeable reference. That night at Anfield, the old brigade were taught a footballing lesson by the young, exuberant Dutch.

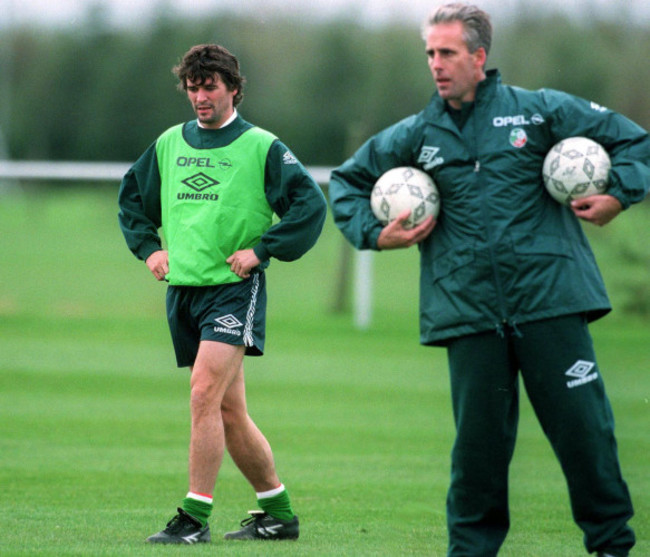

McCarthy was well aware. In came the likes of Gary Breen, Ian Harte, Keith O’Neill and Alan Moore in an effort to rejuvenate the squad. As a result, there was pressure. And with Charlton’s side having endured a humiliating time in Eschen last time they visited, there was plenty of scar tissue to deal with too.

Paul McGrath had featured in two friendlies under McCarthy but was left out of the travelling squad for the trip to the principality. For Jim Duggan, who was brought on board to direct the documentary (subsequently titled McCarthy’s Park), it was an early dramatic plot-line.

And, as it turned out, there were plenty of them along the way.

“In terms of access, we were blessed to get what we did,” he says.

“The big challenge was striking up a rapport and making sure everything was easy and comfortable for everybody. The Graham Taylor doc was still a hot topic at the time and everyone was conscious that – depending on how you used the material – how would you make somebody look? It was a challenge getting everyone to understand that it was about telling the story as we saw it and not necessarily creating anything else.”

In the aftermath of the 5-0 win and a solid competitive managerial debut for McCarthy, storylines continued to follow him around. After a comfortable home victory over Macedonia, there was Roy Keane’s return to the fold the following month for a clash with Iceland at Lansdowne Road.

Keane had been immense for Manchester United and was crucial to the side claiming a Premier League and FA Cup double for the second time in three seasons. It had been a gruelling club campaign but McCarthy had some friendlies scheduled and had also pencilled the Irish side in for the US Cup that summer. He named Keane captain for the tour but the midfielder had little desire to make the trip and, instead of speaking to McCarthy in person, left it to United to inform the FAI that he was unavailable and badly needed time off. When he didn’t show up for a clash with Portugal in Dublin and was instead spotted at the Old Trafford Cricket Ground, McCarthy went in hard when discussing everything with the press.

“I need him to show the desire to play for his country,” he said, foreshadowing the future.

“I want players with me who are as committed to playing for Ireland as those out there in training today. I have no intention of chasing people to come and play for Ireland. Either they turn up and play or I get on without them. It is as simple as that.”

Of course, there was history.

In McCarthy’s first game in charge – a home friendly with Russia – Ireland were picked apart as Alexandr Mostovoi gave a midfield masterclass. A frustrated Keane, who had taken the armband when Andy Townsend was substituted, was sent-off for a wild lunge late on. It was an unnecessary talking point for McCarthy to deal with and he was irked. And it fed into a wider tension between the pair that had its seeds sewn in 1992, when Keane – worse for wear after a solid drinking session – was late arriving for the team bus as it prepared to take the squad to the airport after a tournament in the US. Charlton called him out. Keane – on his first senior tour with the team and who’d only made his debut the previous year, fired back. When McCarthy stepped in, Keane didn’t shirk that challenge either and certainly left his mark.

Keane’s behaviour in the summer of ’96 hadn’t just irritated McCarthy but quite a few journalists too. One in particular, Cathal Dervan, encouraged Irish fans to boo Keane during his comeback game against Iceland. The narrative was simple: Keane clearly didn’t care about his country.

Over two decades later, it remains a remarkable moment to look back on. Keane, selected as a sweeper that afternoon, was roundly abused by his own supporters when he got some early touches. Eventually, the hostilities abated but the tension lingered. Ireland were limp and lifeless. After the game, John Aldridge, annoyed by a lack of action, informed McCarthy that he was retiring with immediate effect. The 0-0 result led to a stand-off between a prickly McCarthy and the media afterwards. But what’s most striking is that McCarthy never criticised those Irish fans who booed Keane that day. He commented about the poor atmosphere in the stadium but fell way short of backing his player and diffusing the questions about Keane’s commitment.

“There was a lot of stuff happening around Mick so it wasn’t hard to find the drama,” Duggan says.

I think the documentary was always going to be through his eyes. I don’t think there was ever a desire to sit down with Roy or any of the players. I’m not sure if there were any requests to speak with any of the squad. It was about Mick and his journey, him starting out on that campaign. There were some players who had some moments during the qualifiers but it was never about their individual moments because it was always seen through Mick. They were little bricks in the bigger story.”

“We wanted to make something a bit more different from ‘Ole, Ole, Ole – let’s follow the fans’. I think we were all looking for something more than that, including Mick. Which was great news because that’s why we did get a bit more access than just fleeting glimpses of him getting off the team bus. Everybody was up for getting behind the curtain a little bit and letting people see what it was like.”

“With Mick, what you see is what you get. There’s no pretence about him. In as much as I have to say about anyone’s character, he always struck me as a really straightforward, honest guy who loved his football, clearly loved Ireland, loved playing for and managing the Irish team and somebody who was a really good family guy. Family was very important to him and he understood the rigours of football and what it meant for his wife and kids.”

Midway through the campaign, everything crashed through the floor. There was an embarrassing defeat in Skopje, McGrath’s brief return to the squad was quickly over when he was left out of that trip, the atmosphere in the camp was strained and on the eve of a hugely-important clash with Romania in Bucharest, a report was leaked claiming McCarthy would resign if the team suffered another loss.

1-0 down, Ireland were awarded a penalty in the second-half but Keane’s effort was saved by Bogdan Stelea. Perched next to the bench, Duggan was perfectly placed to catch McCarthy furiously volleying the dugout in disgust.

There are other moments speckled throughout the documentary that capture the pressure-cooker environment and the impact football management has, not only on the main protagonists, but their families too.

One scene features McCarthy and his wife Fiona discussing the wider stresses of the job.

“It’s what I do, it’s not who I am,” he says.

Was it a worry for Duggan when rumours began to circulate about McCarthy possibly walking away? What would that have meant for the documentary? Was there a contingency plan?

“Television is full of programmes that start out thinking they’re going to tell one story but end up telling another,” he says.

“There’s always a roll of the dice when you set out on something that doesn’t finish for eighteen months in terms of what sort of story you’re going to be telling at the end of it. If you qualify, it’s one story. If you don’t, it’s another.”

As it turned out, Duggan did get his longed-for crescendo.

After another dispiriting draw at home to Lithuania, McCarthy’s side needed six points from back-to-back away trips to Reykjavik and Vilnius. Somehow, they got them. And everything led to a play-off against Belgium.

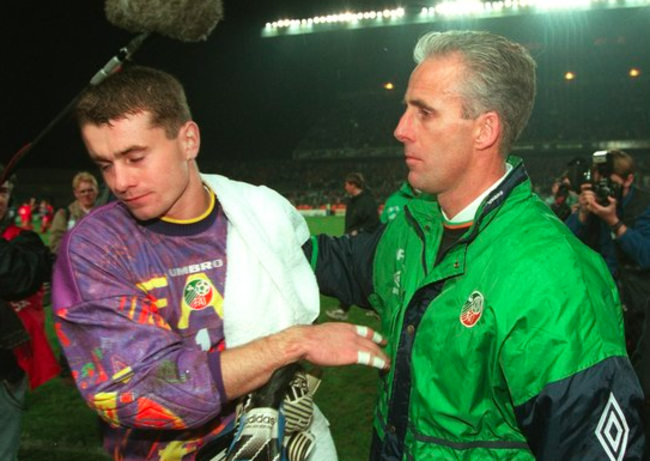

After a 1-1 draw in Dublin, it all came down to one final battle in Brussels. When Ray Houghton cancelled out Luis Oliveira’s opener just shy of the hour mark, there seemed to be a chance. But Luc Nilis later netted a controversial second for the hosts and Ireland were out.

“Anyone that was in the stadium will never forget that night,” Duggan says.

“It was just an epic. An away game, thousands and thousands of fans. I’m not sure I’ve ever heard the national anthem sung that loudly in the Aviva, not to mind in an away stadium. It was bucketing down rain. It was just one of those stories. It would have been brilliant if that night ended in qualification but, even though it didn’t, I still think it’s one of those epic nights for Irish football.”

One of the standout scenes in the documentary is when McCarthy is waiting to conduct an interview with RTE’s Peter Collins moments after the full-time whistle. McCarthy’s wife, Fiona, unexpectedly rushes through the lineup of cameras and reporters and the pair embrace. For McCarthy, a man who doesn’t show much in the way of emotion, it’s a rare moment of vulnerability.

And, shortly after – despite the circumstances – he stayed true to a commitment he’d made to the documentary crew.

“Mick was good enough to agree to an interview very soon afterwards,” Duggan says.

In those days, that whole thing you have now of doorstepping a manager on the sideline and saying, ‘You’ve just lost 4-0, what’s the story?’ – you just didn’t get that at the time. But, come hell or high water, he said he was going to give us an interview and we got it and it was raw. Back then, you didn’t always get to see a manager after a two-year campaign saying, ‘What a pain in the arse that was’. But that was part of the story and it’s a mark of the man that he was willing to come out and show us how he felt.”

“In as little as I got to know him – pointing a camera at him for a few days every couple of months – I admired him as a character and a guy. He understood he needed to give us access so that we’d get something but at the same time he’s a cautious enough guy and was cautious enough about opening up too much.”

A few months later, McCarthy dropped by to watch a cut of the documentary and was impressed. He had no issue with any of the content and he was particularly pleased with the way Duggan handled two sequences.

“I don’t think he gave us anything that he didn’t want to give us.” Duggan says.

“He was ahead of the game there in the sense that there wasn’t anything he said to us that he’d have been unhappy for us to use. And I don’t think there was anyone in the production team or in RTE interested in saying, ‘Let’s take this out of context and see if we can pull the pin in this grenade’, Everyone was honourable in what they were doing.”

One of the bits he liked was a training sequence that we got a lot of great stuff at. Everyone was up, Mick was good, the players were good, there was good banter. He thought that was a really good representation of what the day was like. But there was another moment when Princess Diana died. And I found that really interesting – the shots of the players and the coaching staff all watching her funeral on the TV when the team were in Iceland. I remember Mick saying he was worried about how that would be used and if we’d be honourable with the footage. But when he watched it back, he felt it was well represented.”

Over 20 years on, McCarthy’s Park remains a fond memory for Duggan, a prolific editor of various dramas and documentaries and who went on to serve as Managing Director of Screen Scene, the Irish post-production heavyweight. He retains a soft spot for McCarthy and is buoyed by his return to the Irish fold.

“I’ve only ever directed two things and don’t ask me what the other one was,” he says.

I’ve done a lot of editing and have a lot of fond memories of that. But McCarthy’s Park was the only thing where I was out and about doing it. There was a tight team working hard and I’m a football fan so I was getting that look behind the curtain. There was a moment when you could enjoy being at that second leg in Brussels but, at the same time, you had to make sure you were capturing it and that you didn’t just put your head in your hands and start crying when Belgium scored that second goal.”

“I thought it was interesting when Mick took the role again and he said how he understood now that the media had a job and that he had a job. Maybe the last time he wasn’t as sure. Way back when, I’d say he was a bit more cautious regarding how he interacted with the media. But that’s like everything. He has loads of experience now in terms of dealing with he press so I’d say he’s a bit more chill.”

“I think the FAI probably thought, ‘Jesus, we can’t believe our luck here – a really experienced guy who’s available at this moment in time, he has the background, a good fella, we all know him’. And for him to go, ‘Yeah, I’ll walk away in two years’. Somebody in the FAI must have been saying their prayers that night.”

Subscribe to our new podcast, Heineken Rugby Weekly on The42, here: