DAMIEN RICHARDSON CAN pinpoint the exact moment that he fell in love with football.

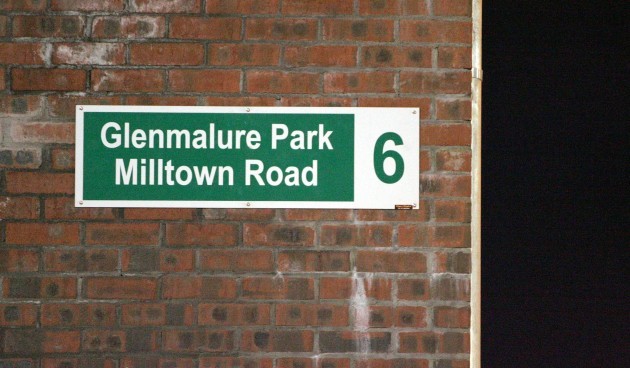

“I remember going to Milltown when I was seven years of age,” he recalls. “It was my first time and we went one Sunday afternoon for a Shield game in early September.

“Shamrock Rovers were playing Drumcondra. There were huge crowds and you could feel this sense of excitement queuing outside Glenmalure Park. I was lifted over the turnstiles, the place was packed. We were down at the front of the terracing where the goal was and you had to stand on your tippy-toes to look over the wall.

“All of a sudden, I was exposed to a scene that still lives with me to this day. We had arrived in late and the game was already started but the colour was just amazing — the green and white hoops of Rovers and the yellow and blue of Drumcondra. The pitch was in pristine condition too.”

Brought up in Maryland, just off Cork Street in Dublin’s south inner city, the Richardsons moved to Lombard St at the back of the Meath Hospital, which he says was either Rovers or St Patrick’s Athletic territory.

Damien’s father George had played League of Ireland with Brideville and Bray Unknowns before managing Pat’s, but didn’t support any one club. That afternoon, the youngster decided he would become a Hoops fan, while his brother chose Drumcondra.

“I think he did that more to annoy me than anything else!” he laughs. “From then on, my love for Shamrock Rovers was encased in stone. That Rovers team were enshrined in the history of the League of Ireland. I can even tell you the team now.” He begins listing off the line-up: “It was O’Callaghan, Burke, Keogh, Mackey, Nolan, Hennessy, McCann, Tuohy… That side really brought the game to the fore for me.”

Long before that eye-opening experience, Richardson had already been developing his own talents in various locations around the capital.

“Essentially, I learned football on the streets of Maryland and Oriel St in the North Wall, where my grandmother lived. I used to be down there every weekend. It was street football and very rarely did we go to the park, although we would the odd time.

“Football was a passport for me and my brother. We’d go to Finglas, Cabra, Kimmage or wherever our relations lived and because you were quite decent you would mix with anybody. People had respect for you if you could play a little bit.

It began on the streets and still to this day they are part of what I am.”

From the age of 12, he joined one of the top clubs in the country — Home Farm. At schoolboy level, he played a year older than his age group and found it hugely beneficial in improving his skills. Small in height initially, Damien took a stretch at 16 and soon realised that he was now better than most of the other boys.

In 1965, an unprecedented situation saw Home Farm’s A team meet Richardson’s B team in the FAI Youth Cup final at Tolka Park — the only time two sides from one club faced off in that round of the competition. It took two replays to separate them, but the A’s eventually edged it.

A week before that, Richardson was invited up to Richmond Park. Rovers were playing in a testimonial match and player/manager Liam Tuohy, a man he had idolised for many years, asked him to play.

“I didn’t have boots or anything with me so I had to borrow a pair,” he explains. “You wouldn’t be allowed do it today because I was still with Home Farm and you’d have to get clearance. I was put in centre forward that night, a position I had never played before because I had always been a midfielder. I scored a goal quite early in the game and played well.

“Tuohy saw something in me that I didn’t know I had. A couple of weeks later we played in the Youth Cup final but by that time I had made my mind up that I was joining Rovers.”

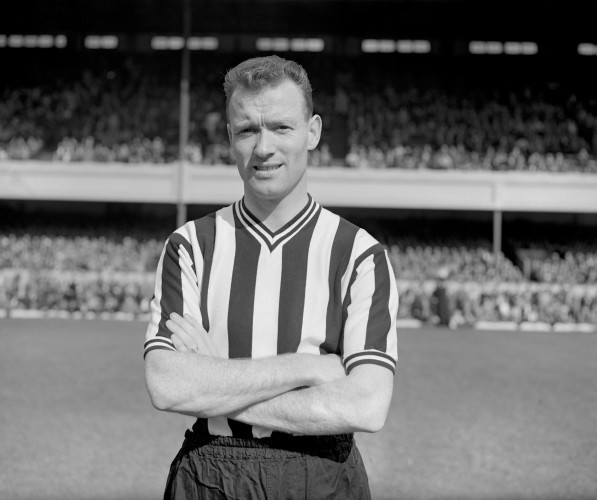

Having watched the great Rovers side of the 1950s, the teenager was about to share a dressing room with several of those same players he looked up to as a boy.

“It was quite daunting but also exciting,” he tells.” Tuohy had been a hero of mine and having him call around to the house caused consternation in the street. There were kids lined up outside in the front garden as me, my dad, Liam and the scout Gerry Moran discussed my move.”

Joining his boyhood club was a no-brainer and Richardson was a Hoops player a couple of months shy of his 18th birthday. By the age of 21, he had already won two FAI Cups as the club made it six in-a-row.

Understandably, he admits having to pinch himself: “I had been to all the cup finals and watched them play. Now I was involved in the last two.

“It was a stunning achievement in such a short period of time. That Rovers team were used to success. In those days, the cup was the preferred competition because there was more money involved in winning it.”

That was undoubtedly a golden era for domestic football in this country, but when the Cunninghams sold the club on after four decades in charge, it spelled the end of that remarkable success for Rovers.

“We used to get 20,000 watching games but there was never any investment put back in,” Richardson says. “When Joe and Mary Jane Cunningham moved on, there wasn’t the same love for the game from the young people and gradually the club started to go down hill.

We went from 20,000 to 12,000 and all the way to 3,000 and it wasn’t the same place. The spark had gone. An attendance of 3,000 sounds great now but in those days it wouldn’t have been anywhere near what we expected. That was the beginning of the end of the great times in League of Ireland football.

“It was happening all around the country too and the sad part of it is that it wasn’t a gradual demise. It was too quick for my liking but that was the way the country was moving. Sunday afternoon was no longer just about football.

“Football suffered the effects of society changing its habits and it had a knock-on effect with Shamrock Rovers and the League of Ireland as a whole.”

When he was 21, Preston North End had attempted to bring him to England after a recommendation from former Rovers captain Johnny Fulham. An offer came in, a fee was agreed and he made his mind up to go but then the transfer fell through.

Richardson was later led to believe that the secretary had naively chanced his arm and pushed for more money.

“When that happened, I wasn’t shattered by it,” he says. “I was playing for Rovers and making good money. They got me work in Volkswagen on the Naas Road. It was a terrific job with very little work to do but the money was fabulous.”

A few years later, Gillingham expressed an interest after ex-Manchester United goalkeeper Pat Dunne tipped off their manager Andy Nelson about a decent target man playing in Ireland. By then, the atmosphere at Rovers had taken a turn for the worse and Richardson was keen to test himself in the professional game.

“I was just gone 24 at that time, which in those days was too late to go over. It’s a different game now. You go over and people respect you have a whole career ahead of you at 21. If you go at 24 in those days, half your playing career is effectively gone.

“I joined Gillingham and took a drop in money but going full-time was what I wanted to do. Any player worth their salt would like to give it a go.

“It was a dream come true that I was now a professional footballer and it gave me an added confidence. Andy Nelson was a top quality manager and I was hugely impressed with him. He made me an even better player than I was a Shamrock Rovers.”

He would go on to spend nine years at the club — scoring 102 goals in all competitions as they won promotion to the old Division 3.

“The first two or three years there were the happiest period of my football career,” he reveals. “We had a first class manager and won promotion the following season. We were getting crowds of 12,000 to 15,000 that year and it was a great atmosphere.

“The camaraderie that Andy created by signing good players was wonderful to be involved with. There was varying degrees of ability but one thing they had in common was a bond to be a good team.

“You trained every morning and went to bed in the afternoon. That suited me down to the ground, and then I would get up and pick the kids from school.

Kent is the garden of England and it was a wonderful part of my life. It was a great place to bring kids up and I stayed at Gillingham longer than I should have.”

At international level, Richardson earned a total of three senior Ireland caps. Called up first by Mick Meagan for a European championship qualifier away to Sweden, he didn’t get on the pitch as the Boys in Green performed well but lost out 1-0.

He had to wait a little longer than expected to be included again and blames the workings of the FAI at that time.

“The manager put his squad into the FAI, but somebody in there deleted my name from it,” he claims. “Before the managers demanded control, the squad could be changed by people within the association after it had been submitted by the manager. That’s how amateurish it was.

“If you had a connection with the FAI as a club manager, you could promise players an international cap if they signed for you and then get them into the squad. It was frustrating for people like Mick, who was ultra professional about everything in the game.”

As fate would have it, old mentor Tuohy handed Richardson his debut against Austria in 1971.

“It was essentially a League of Ireland team because the game clashed with English fixtures. Paddy Mulligan, who was with Chelsea, was the only one who played from over there. We got beaten 6-o but were unlucky that day and it wasn’t as bad as it sounded.”

He later donned the green under Sean Thomas and, subsequently, during John Giles’ time and remarks on the noticeable difference in standards as the years went on.

“It had become very professional and Giles created a good team spirit. It was almost like a club team, with sing-songs and all that. Playing for Ireland added a huge amount of experience to me. Working with big players and watching top managers in action was great preparation for my own managerial career.”

Let go by Gillingham in 1981, Richardson admits finding it extremely difficult to re-adjust to life and accept his time as a full-time player were over.

“In those days, 32 was a cut off point. There weren’t the levels of fitness and the sports science there. That was a very dark period in my career and my life. You walk in on a Monday morning and you’re a professional footballer, then you leave that day and you’re no longer one.

“It’s a bad blow in many senses — psychologically as much as anything else. It’s a part of football that I just don’t think has been addressed properly. In those days in particular, there was no preparation at all.”

He decided to keep up playing with various non-league clubs while take a job selling double-glazed windows. Then when John Gorman, who later worked under Glenn Hoddle with England, was promoted to Gills assistant manager, Richardson was offered the role of youth team boss at his old club. Management and coaching hadn’t necessarily been on the cards, but he decided to accept the position.

I was making very good money and went back to be youth team manager for little or nothing, but it was something I wanted to do. I had a BMW Seven Series that I had to sell and take a Vauxhall Cavalier, which is what you were given on the youth team. I went back and did really well. We were competing with all the London teams in the South East County League.

“It was a terrific two-year period for me. Spurs and Arsenal were the top two teams and we finished third a couple of times, which we had never done.”

With money tight and results not going well, Keith Burkinshaw resigned as Gillingham manager in April 1989. Several candidates, including ex-Ireland boss Eoin Hand, applied to replace him but they instead turned to Richardson — even though he had shown no interest.

Despite being warned not to take it by Burkinshaw, who felt they needed a more experienced man, he said yes.

“Everything Keith had told me was true,” he accepts. “He said there was no money, and there was none. I had to sell all my best players.

“Gavin Peacock was sold to Harry Redknapp at Bournemouth and he ended up at Newcastle. And there were loads of others. I had to replace them with youngsters.

“The directors weren’t honest and they only appointed me because I knew the youth team players. I was a stop-gap manager. I had to promote the kids and get the best out of them.

“The mistake I made was that I didn’t bring in someone experienced with me. My naivety cost me but I learned valuable lessons and never let that happen again. It’s part of the cynical aspect of football but I never lost my love for it.”

That spelled the end of his football career in England and Richardson was appointed Cork City boss for the first of two spells in 1993.

“I came over and joined Cork but I learned a lesson and didn’t let directors or chairmen boss me about. I knew what I wanted to do and I came to Cork a different manager. I wasn’t going to make the same mistakes again.

“I took over Cork after they had won the league and they were a very good team. Declan Daly was the captain, then there was Dave Barry and Pat Morley.”

Rico’s first game in charge was a European Cup tie against Welsh outfit Cwmbran Town. Despite going 3-0 down inside the first half, they pulled back it back to 3-2 before progressing on away goals after a narrow win in the return leg.

“That really made me aware of what Cork City was all about. Turner’s Cross was packed, you had people standing on walls, and when we won the next day, the sponsors Guinness plastered the city with advertisements featuring pictures of the game.”

That set up a tie with Turkish giants Galatasaray, and the winner would go on to face Manchester United in the next round.

“So we went to Istanbul and lost 2-1 out there, which was without a shadow of a doubt the greatest experience I’ve ever had in football. We got to the ground about two hours before the game and the stadium was absolutely rammed.

“Walking out onto the pitch, the reception we got was staggering. There was a ferociousness from their supporters and they made it known that we weren’t welcome.

“They thought they were going to beat us well as we were part-time. I played up to that and said we should be pinching ourselves that we were in the same stadium as this big club. They didn’t score for the first 25 minutes but it was almost worth it to see the reaction. The place looked as though it had gone on fire — there were flares everywhere and the colour was quite astonishing.

“Never have I seen anything like it. When Steve Bruce went out there in the next round he said the very same thing. It was amazing.

“They scored two goals and they thought the job was done. Then we hit them through Dave Barry and all of a sudden they woke up and belted us but couldn’t get that third goal.”

Ahead of the second leg in Bishopstown and trailing 2-1, Richardson used some underhand tactics in an attempt to upset the opposition’s preparations.

“The night before the game, Galatasaray trained at the ground and I spotted one of their officials pacing out the pitch. Then he went to the manager and gave the dimensions. I thought ‘That’s interesting’.

I called my assistant and told him what happened so we decided to come in the following morning and narrow the pitch.

“When they arrived for the game, it caused consternation. They informed Uefa delegates, and I was called into a meeting. I said ‘Listen, it’s our pitch. We can do what we want’.

“The Uefa delegate agreed and it worked a treat. On the back of things like that, they’ve changed it so you have to put in the dimensions beforehand.

“We only lost 1-0. Kubilay was superb and he got the goal that killed it. Then they went to Old Trafford and threw 3-3 before holding them to 0-0 at home to knock Man United out. It was a great occasion.”

Richardson also credits another European opponent, Slavia Prague, with forcing him to rethink his training methods and put more of an emphasis on the technical side of the game.

After 18 months in the job, Richardson departed Cork — citing a breakdown in relationship with chairman Pat O’Donovan over players’ wages.

“I fell out with Pat because wages were late. He was trying to build a stadium, which I understood, and things were very tight financially.

“As manager, the players were coming to me and Pat and I had several, big fall-outs. In the end, I had no option but to leave because he wasn’t allowing me to protect the players. It caused shock waves in Cork and there was trouble over it but I’ve always been proud of the fact that I made my stand.

“I know that it was well-received in Cork because at that time the chairman had a bad name for not paying people so everyone understood.”

After a brief stint with Cobh Ramblers, he was handed the reins at Shelbourne as a replacement for Colin Murphy.

“Colin is an articulate man and someone I got on with, but he was a bit of a bluffer,” Richardson says. “He knew he was and he wanted a way out. I met with [chief executive] Ollie Byrne and [chairman] Finbarr Flood and took the job. There were some good players there but I said to them ‘If you employ me, you employ my ways. My philosophy’.

All down through the years of me following the League of Ireland, Shelbourne was the one club that always insisted the team play football. They had a superb ethos and you had to play football — even more than Shamrock Rovers.”

Under him, Shels won an FAI Cup and League Cup double in ’96 before retaining the country’s top cup competition the following year.

“Ollie was delighted and I remember him saying ‘We can become the cup team of the 90s’. It was a particularly good team and we played a great brand of football. Ollie brought Tony Sheridan back from England. He had more connections than all the electricians in the country. We had Pat Scully, Tony McCarthy and also Stephen Geoghegan up front. Then I signed Pat Morley and Pascal Vaudequin.

“At the time, I took great delight in saying Tolka Park was the entertainment capital of Ireland. We got good crowds and there was some super football.”

But it was to end on bad terms between the late Byrne and Richardson, as he explains.

“The first two years were brilliant, but then something happened between me and Ollie that I’ve never quite been able to put my finger on.

“I was very popular with the Shels fans because of the style of football. I used to come out on a Friday night and I’d get a tremendous round of applause walking up to the dug-out.

“Ollie was Mr Shelbourne and he was a bit like Donald Trump in that he had to have that ego massaged. We all have it in football and that’s nothing derogatory towards Ollie but that’s just the way he was.

“There little bit of friction started between us. It might have been a little bit of jealousy that I was too well-received.”

We were fighting Pat’s for the league but in the end we lost to Dundalk. We didn’t perform to the level that day. We were beaten in the cup final by Cork City and it had gone beyond repair between me and Ollie by then.

“He used the defeat in Dundalk to further widen the void between us. We negotiated a settlement but in the last minute Ollie wanted me to stay. I had made my mind up by then and left.

“I was delighted with the foundations we put in at Shelbourne at that time. It was a joy to work with Ollie and Finbarr — two very different characters. I could tell you hundreds of stories.”

Over the years, Rico has become well-known for the eloquent language he used during interviews and in his famous programme notes — the joke being that you’d be advised to carry a dictionary if you were reporting on one of his teams.

He wears the reputation as a badge of honour and believes its originality has helped promote the league at times.

“I do take great pride in that,” he says. “When I joined Shamrock Rovers, I used to read all the papers and listen to Philip Greene on RTÉ Radio. He was a great LOI man but even more than that he was a great Shamrock Rovers man.

“Tuohy always had a great way about him when he was interviewed. He wasn’t the most articulate but he was full of fun. He was my hero and I admired everything about him.

One of the first interviews I did was when Jimmy Magee asked me to go into RTÉ Radio studios, which at that time was in Henry St in Dublin.

“I was quite eloquent in what I said and when we were walking out Jimmy said to me ‘See the way you spoke there, most journalists wouldn’t be able to do that. Think about that’.

“Jimmy said similar things over my career and it just got me talking. I learned from him to slow your words down and pronounce them properly. I learned the art of the interview and the value of it.

“When I was young, everyone had elocution lessons. I think it’s part of the Dublin I grew up in.”

He adds: “I did my programme notes over in England and realised they were all the same. I even stopped reading them. So I decided to change mine and make them more informative. I started to tell people what was going on behind the scenes and doing it in a way that is as attractive as possible.

“When I came home, there were far more allowances and we didn’t take ourselves as seriously as the English. I took it a step further with my notes. I could go to a different galaxy, and it was almost done in tongue-in-cheek. It took on a life of its own, which was great.

“We needed to make the game as attractive as we could for people outside. The LOI was often seen as a poor relation to the GAA, played in bad conditions. Pat Dolan used to do the same at the time. He was a good interviewee.”

His next managerial job saw him return to the club he supported– Shamrock Rovers. But sadly, a lot had changed since he had been away, and not for the better either.

“The only connection with the team I left all those years back and the one I joined were the green and white hoops,” he says. “We had 18 different training venues the first year and the one we used most was the public park out in Clondalkin.

“We played out in Santry, which was too small for a pitch. The running track meant the crowd was too far away. Not only was it a venue that I didn’t enjoy, I found it very difficult to motivate myself to go there.

“To be fair, it was the way things were. If you can’t change the conditions, then you make the best of them and I thought we did really well.

“When I joined Rovers, they weren’t in a good state and when I left they had just qualified for Europe. When Liam Buckley took over, his first game was a European tie.

I was proud of what I did at Rovers during that difficult time. The real frustration for me was that we couldn’t train on the pitch in Tallaght while they were building the stadium.

“We trained on the it without people knowing about three or four times, but then we were stopped from doing so.

“Usually for training, players would come, change in the car, train, and go home to have a shower. That was a professional outfit at the time. It was a very tough spell and the fact that I left the club before they got into Tallaght was an element of frustration.”

Between 2002 and 2005, he took a break from the LOI and did some work in the media as well as bits of coaching here and there. That was until the Cork job came up for a second time.

“There was unfinished business at Cork City. Pat Dolan, Liam Murphy and Dave Barry had been there before me and they all left their imprint on the club.

“The chairman Brian Lennox brought me in simply to win the title but I said to him ‘I’m going to come in and it has to be done according to me principles’. He said ‘If you take the job, you can do it the way you want but you have to win the league’.

“So I went in and changed things, changed attitudes. Shelbourne had won the league the previous year and they were the team to beat. We played them in the Blacksmith the week before the season started.

“Cork hadn’t beaten them at all the previous season but won that day with Denis Behan scoring the winning goal, and that really got our season going.

That year, we won the league title in the most dramatic fashion — the last game of the season at Turner’s Cross. It was the perfect finale.

“Although I’d signed a two-year contract, had I not won the league then that would have been the end of it. That was the conditions I had accepted.

“One of the most satisfying moments of my career was that we stayed true to our values on the most demanding night. That will always be a great source of pride for me personally.”

Trailing leaders Derry City by a point heading into a title-decider at Turner’s Cross, the Leesiders claimed a 2-0 win to become top flight champions for only the second time in their history.

The achievement is even more impressive when you consider that Richardson spent a week in hospital during the season after blood clots were found on his lungs.

“First of all, that team had unique Cork character,” Richardson says of the side. “They would never give up and their attitude was first class. We had some good players. Neale Fenn was the catalyst, although he got injured in the last game and Behan came on to help transform it in his own unique fashion.

“There was John O’Flynn, George O’Callaghan and Michael Devine. There was good quality throughout the team and they bought into the philosophy.

“When Kevin Doyle and Shane Long left, people thought it would hurt us badly but Fenn came into his own on their departures and he was very influential that season — albeit in a fashion that is often overlooked by people.”

In stark contrast to those highs, Cork City was cast into turmoil in the years that followed.

“I made the mistake, despite the huge experience I had, by not letting the players aware of the situation. I couldn’t sign players and we dropped a little bit.

“Brian guaranteed he would always pay the wages but he added that he couldn’t invest in the team. I said the players getting paid was my priority.

“We got through that period and won the FAI Cup in 2007, maybe on the back of a clear-the-air meeting.

Brian sold the club, unwisely as it turns out, and to the wrong people — Arkaga. That was no fault of his because they were very plausible when I met them, but the one thing that struck me was that every time you met them it was different people.

“Brian had to do it after putting a huge amount into the club but that was the beginning of the end because they were strange, strange people. They appointed a man called Aidan Tynan, who had no idea what professional football was about. Not the faintest idea.

“He listened to advice from a certain quarter, which I’m not willing to mention at this time, that sent him in a direction that was totally at odds with what the club stood for at that particular time.

“Everything fell apart on the back of his appointment. It went from bad to worse and Tom Coughlan came in, who took a lot of stick and to a great extent rightly so. But it wasn’t all his doing as the deep-rooted rot had set in before he arrived.”

Departing Cork after their FAI Cup triumph in 2007, Richardson stepped away from top level management for a period. During the summers of 2010 and 2011, he was invited to take charge of a League of Ireland XI for pre-season friendly matches at the Aviva Stadium.

He chose not to make it public back then, but he was also diagnosed with prostate cancer around that time.

“That took a bit of getting used to,” he admits. “While I was working in the media and doing other bits, I went through the treatment. It wasn’t successful though. I left it for awhile and I was seeing a specialist in Dublin and Galway.”

When Richardson took the Drogheda job in 2014, there was still a tumour in the back of his prostate.

I had the others cleaned out but I still had one spot,” he adds. “So I had to have an operation last year in Surrey. That was my prostate removed and the tumour came out with it. Thankfully, there was nothing around it so everything is good.”

One why he decided to only share the information with immediate family, he explains: “Ireland is such a great place in that no matter where you go people will know you and want to talk about football. I used to loved that, even going into town — no matter if you were in Cork or Dublin — and people coming up to talk to you.

“I didn’t want the first question to be ‘How are you feeling?’. I wanted people to chat about football or politics or whatever else. So I didn’t make it public, but now that it’s all behind me and everything is good I have no problem talking about it.”

His stay at Drogheda was short-lived and these days Richardson is based in their house in Kent — where he is enjoying being able to spend time with his wife, children and grandchildren.

That said, at 70, he remains actively involved in football and just last week announced that he is the new director of coaching at Carrigaline United in Cork. That will involve coming over four or five days each month to pass on his knowledge and experience to the 60-plus coaches working at the current FAI Club of the Year.

In schoolboy clubs, it’s more important to coach the coaches than the players. You’d want to be superman to be able to coach all the young footballers.

“So the best way is to influence the coaches and improve their education. I always had a plan to do that in the back of my head. Denis Behan, who used to play for me at Cork, is now their senior team manager and he approached me.

“Coaches don’t get enough backing. The FAI do what they can but coaching badges are a little bit artificial. It teaches them organisation and an awareness to certain situations, but they won’t get to the nitty gritty of what schoolboy football is all about. Coaching and management are things you only learn through experience so I hopefully I can pass on mine.

“Carrigaline United is the perfect example of inclusion of all age groups and levels of ability. It’s everything I feel a football club should be.”

Subscribe to The42 podcasts here: