As we close the book on the sporting year and get ready for another massive one, we’re looking back on some of our favourite pieces of sportswriting published on The 42 in 2023.

Today: Ciarán Kennedy travels to Wigan to meet the coaches and players that shaped Ireland’s head coach Andy Farrell.

If you enjoy this piece, and would like unlimited access to all of our news, analysis, podcasts and sportswriting in 2024, you can sign up today at the42.ie/subscribe.

***

THERE WAS A time during his underage career where the ruthless killer instinct which would later define Andy Farrell deserted him.

His Orrell St James’ team had made a habit of clocking up big wins. So to keep things competitive his coach, Haydn Walker, introduced a rule: if a player scored more than three tries, they’d have to come off. So for a while, this prodigiously talented kid’s greatest challenge was staying on the pitch.

“There was plenty of times where Andrew had already scored three,” Walker says, “and he’d break through and be holding the ball for somebody because he didn’t want to come off!

“He was just an ordinary kid, but there were times where we’d do things together, like go 10-pin bowling, and he had to win. Everybody else was mucking about, having a laugh, and he just wanted a strike every time. And if he didn’t get it, he wasn’t happy.”

Over the course of an early morning coffee in the leafy Wigan suburb of Orrell, Walker will repeatedly describe Farrell as an “ordinary kid”, while also making it clear that Farrell was never really like most young rugby players.

There’s not many tourists on the morning service from Manchester to Wigan, so on a sunny Tuesday in mid-April, The 42 has the luxury of an entire carriage to ourselves.

From Wigan North Western station, it’s about a 15-minute walk to our first stop – 25 if you take the wrong turn at the bottom of the hill.

After a couple of false starts we finally reach our destination, which lies just on the edge of the town centre. It’s easy to see how match days here would consume the town. The pubs which previously burst with supporters still stand, but with shutters drawn and peeling paint. Andy Farrell’s father used to point to the floodlights which towered over Central Park on the drive to Sunday dinner and remind his young family: “Heaven’s there.”

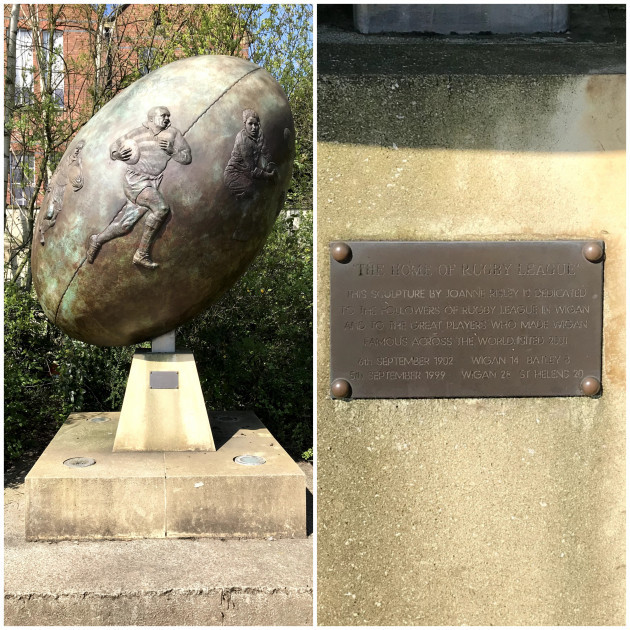

Has Joni Mitchell ever been to Wigan? A couple of years ago locals complained to Tesco about the condition of the statue at the entrance to their car park – a large bronze rugby ball, bearing the inscription: The Home of Rugby League.

Central Park was more than just a rugby stadium to the people of Wigan. Before the rattle of trolleys replaced the clink of the turnstiles, some even had their ashes scattered here. Its demolition marked the end of an era for Wigan Warriors. The club won eight league titles across the 1990s before the ground closed in 1999. It would be 2010 before they were crowned champions again.

Mick Cassidy remembers the days when he would make the short trip to the ground to meet up with Andy Farrell and a couple of other young Wigan hopefuls. From there, they’d jog the two-mile track along the River Douglas until they reached Haigh Hall, a large country house surrounded by woodland.

“There’s a big dirt track called Sennicar Lane, and we used to do hill sprints up there,” Cassidy says. “If you went and beat Andy once, you’d have to go and beat him 10 times after that as well because he would be just chasing you down all the time.”

Cassidy and Farrell both started out at Wigan as teenagers in the early 1990s, and both exited as club legends over a decade later in 2004. Cassidy, two years Farrell’s senior, recalls a young player with the world at his feet.

Even though he was two years younger than me, we kind of came through the ranks at the same time. He was massively talented. I think he could have done anything. He was massively skillful but he was also intense. Always intense.”

Walker remembers a different Andy Farrell. He remembers Andrew. In a hotel just up the road from Farrell’s first junior club, Orrell St James’, Walker sets down an iPad and scrolls through photographs from Farrell’s first years playing a sport that would become his life.

Walker has told this origin story countless times over the years but still delivers it with warmth. It starts in the summer of ’85. Sensing there was something special about the boy in a baggy Blackpool football shirt at a rugby summer camp for U11s, Walker made the trip out to speak to Farrell’s parents in an attempt to coax the youngster into joining his new team.

“He had never played before, and it was like ‘Wow!’” Walker smiles.

He was doing things as an 11-year-old that 15 and 16-year-olds couldn’t. He was just unbelievably gifted.

“But he was very shy, so it took a little bit of persuading, and he came and played for us. He played a pre-season friendly against a local team and we ended up putting 50 or 60 points on them, and he was kicking goals off the touchline at 11.

“But he was gifted at all sports. If he had decided to be a golfer, he’d be number one in the world. If he’d decided to play basketball, he’d be in the NBA. He was just fantastic at whatever sport he turned his hand to.”

********

It doesn’t take long to realise Wigan is a rugby league town.

Walking through Market Place, a couple of locals stroll past in Warriors teamwear. The autobiography of Kevin Sinfield, a legend of Leeds Rhinos, is prominently displayed at the entrance to a large bookstore. Pubs advertise upcoming Super League games live on TV. The colours of cherry and white are second only to those of red, white and blue as the town prepares for the coronation of Charles III, an event marked with entire stalls in the old market and special offers in the crisp aisles at Tesco.

Cassidy points out that Wigan are top of the Super League table and have recently recorded big wins against St Helens and Warrington.

“You’ve come at the right time. You’ll see people wearing Wigan shirts for the next week or so around town now. You do find that if Wigan beat the local rivals, people want to talk about it around town.”

Farrell grew up in the Goose Green area, a 15-minute drive from the town centre. Mid-afternoon it’s peaceful, and very green – Wigan is one of the greenest boroughs in Britain. In the Freemasons Arms, just around the corner from the house Farrell was raised in, locals remember him flying around the roads on his bike as a kid.

A mention of Ireland’s Grand Slam win doesn’t stir up much excitement, but a question about Farrell’s time playing league results in a history lesson on some of the great Warriors days. The big wins at Wembley. Farrell’s bandaged broken nose against Leeds. The last game at Central Park. Hearing The 42 visited the site earlier in the day, they ask if some of the old pubs are still open. Since the club moved out to what was previously the JJB Stadium (now DW Stadium), on the far side of town, they haven’t had much reason to visit.

In any sport, in any context, Farrell’s story is a remarkable one. Signed (unofficially) by Wigan at 14. Turning pro at 16. Becoming a regular in a hard Wigan team at 17. Captaining club and country in his early 20s. Winning seven Super League titles, five Premierships and five Challenge Cups. Doing it all with one club. Doing it all with a ferocious competitiveness that first came to surface in his early teens.

“It wasn’t one of these pushy parents situations,” explains Walker. “His parents were just really, really supportive. But he was the driven one.

“Uniquely, from an early age he’d want to know why. And not specifically why with the rugby team, but why with him – what could I have done better? Which was good, because we used to have all our matches recorded, so you could give him the video and say, well, you tell me what you could do better.”

Word gets around quick in Wigan and the Warriors moved to sign Farrell on an unofficial contract when he was just 14. Reports at the time put the fee involved at around £70,000. While the deal was supposed to be kept under wraps, Farrell’s contract with Warriors was soon an open secret.

The expectation and pressure was rising. Before long, the noises that were previously just whispers on the sidelines grew louder and were being directed at the player.

“Everybody knew he’d signed for Wigan,” Walker continues. “I’m not saying he became a target on the field, because he could look after himself, but there were jealous parents and stuff like that on the touchline.

He took it all in his stride to be honest, but I think there were a couple of occasions where parental abuse got to him.

“Once was at Leigh at around U12s, against our biggest rivals, where a parent, not went for him, but came over and was… less than nice. Unfortunately for this parent, Andrew’s dad was there. It was just jealousy.”

Farrell learned to live with it, and as his development continued at pace, it looked as though nothing would stop his path to a senior career with Wigan.

At this stage the gifted teenager was juggling his club rugby with schools rugby (U15 and U16) and town team (U15) commitments. The demands placed on Farrell were so high that injuries became a concern and at one point his various coaches were all summoned by Warriors to try to cut the young player’s workload. Not everyone in the room was keen to own less of the best young player in Wigan; he’d soon be out of their hands for good.

At 16 he’d turn pro, but in the months before the long-touted dream became real, life changed forever. At 15, Farrell and his girlfriend – now wife – Colleen found out they were to become parents.

“He was under a lot of pressure at that point,” Walker remembers. “But I’ve got to say both Andy’s mum and dad, and Coleen’s mum and dad were just awesome really.

“I will absolutely say that the two families rallied around both of them and put support in place to look after Owen and make sure everything else was ok.

“I think the responsibility, probably as Owen got to be a little bit older, was a good thing for him. He had other things to consider in his life other than rugby, which was all he had ever considered. But I don’t think they would have got through that without the support of the two families. It would have been really difficult for the pair of them.”

If anything, the extra responsibility off the pitch only sharpened Farrell’s focus on it.

“I think that definitely helped him,” Walker adds, “because now he was playing for his family.”