ANDY TURNER STILL loves watching the goal back.

“People forget I got four or five others that season”, he says, mischievously.

“I say to them, ‘What about the Man City one? Or Oldham? Or Brentford?’ And they’re like, ‘Nah, I don’t remember those’. But the Everton goal will always stick out.”

It was Tottenham’s seventh game of an inaugural Premier League season that had begun poorly for them. They’d sacked manager Peter Shreeves, lost Paul Gascoigne, Gary Lineker, Paul Stewart and Paul Walsh and spent heavily on reinforcements. Darren Anderton arrived from Portsmouth and combative centre-half Neil Ruddock was signed from Southampton. Teddy Sheringham was a long-time attacking target but he remained a Nottingham Forest player for the first few weeks of the season, the deal only completed after Spurs’ humiliating 5-0 defeat at reigning champions Leeds.

With the club in the midst of a transitional period, the management team of head coach Doug Livermore and his assistant Ray Clemence did have a steady array of underage talent chomping at the bit for an opportunity to impress.

Turner had come through the youth side and already survived a broken leg when he signed professional terms with the club on his 17th birthday back in March, 1992. He wasn’t expecting any involvement with the first-team but owing to the FA Youth Cup success in 1990 and the likes of Ian Walker, Ian Hendon, David Tuttle and Stuart Nethercott now on the fringes, Turner’s left-wing wizardry and Nicky Barmby’s overall package ensured they were quickly promoted too.

“I remember I was playing with the youth team against Aldershot on a cold January day and broke the leg in a challenge”, Turner says.

“It was the same time as Gazza did his cruciate in the FA Cup final against Nottingham Forest so I spent a lot of time with him in the treatment room, which is a memory in itself. What a great man he is and a great player he was. But once I got fit, I was just relieved to be back because I’d been out for such a long time. I got my head down and I was invited to play in a testimonial against Hull City and I thought I was just along for the trip. There were another few youngsters involved but I was handed a start and I think we won 6-2 that evening. I made an impression along with the likes of Nicky [Barmby] and Stuart [Nethercott] and during pre-season, I was brought into first-team training and played some practice games. I didn’t expect anything because I was a kid and just in awe of being around fellas like Gary Mabbutt, Neil Ruddock and Darren Anderton, who we’d just paid £1.7m for. But then we went across to Glenavon for a friendly that was arranged as part of Gerry McMahon’s transfer and I just sat there and took it all in. I was only seventeen but with the senior group. It was mental. The place was packed, it was really enjoyable and I wanted more.”

On the Thursday before the season started, we were playing a game in training and Nayim – who was a fabulous player, a fantastic person and who played in my position – got injured. I got thrown a bib and it just didn’t really sink in. I played the game and then my name was on the list to go to Southampton away. I travelled down with the team and an hour before, I was named in the starting XI. I don’t remember much because it went so quickly but there are a few things: being up against Jason Dodd, who was an excellent full-back and that the debut lasted about 65 minutes. But there was one thing that happened when I was walking out. I was number seven that day and the announcer was doing the lineups over the tannoy. And he said, ‘Number six, Gary Mabbutt’. And there was a huge roar from the Spurs fans. And then it was, ‘Number seven, Andrew Turner’ and it went deathly silent. There was a just a murmur from the crowd of ‘Who’s that?’ Then the announcer said, ‘Number eight, Gordon Durie’ and they started shouting and screaming again. So that was a bizarre moment, hearing your name read out in a Premier League game when you’re so young. So, like so many players, my chance came along because another somebody got injured. The right place, the right time and doing the right things. It finished 0-0 and it flashed before me. It was an experience you just wanted to get through.”

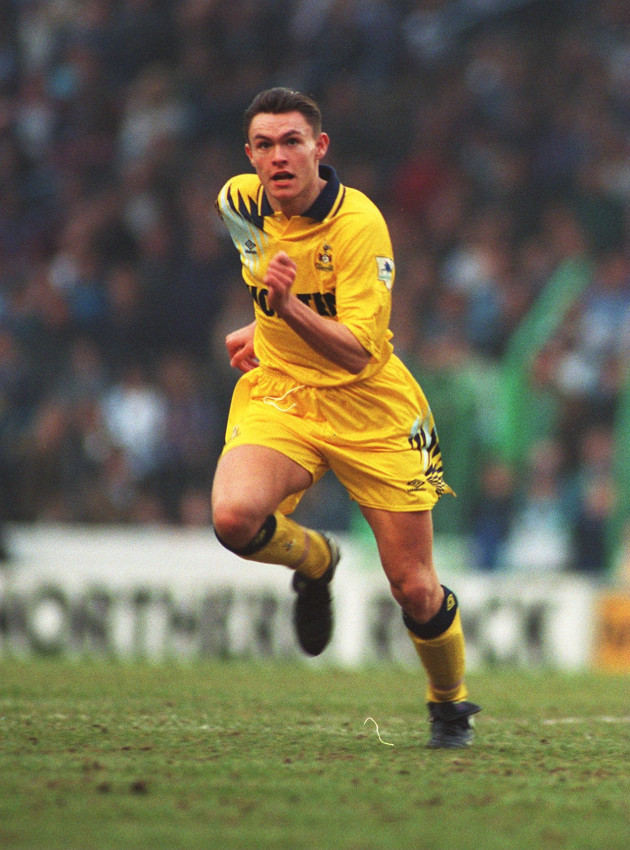

The debut was historic. At the age of 17 years and 145 days, Turner became the youngest Premier League player, though better things were on their way.

Tottenham were trailing to Peter Beardsley’s opener when Turner was sent from the bench to replace an under-performing Anderton at White Hart Lane three weeks later. The hosts had equalised through captain Paul Allen when, in stoppage time, a long throw saw Neville Southall only punch into the path of Turner who rifled a controlled, low strike to the net.

Stunned, he raced along the touchline, unsure of what to do before Ruddock jumped on him and pulled him into a headlock.

‘I didn’t know where to run’, he told reporters afterwards.

Unbeknownst to him at the time, the moment ensured a record that would stand for four-and-a-half years: youngest Premier League goalscorer.

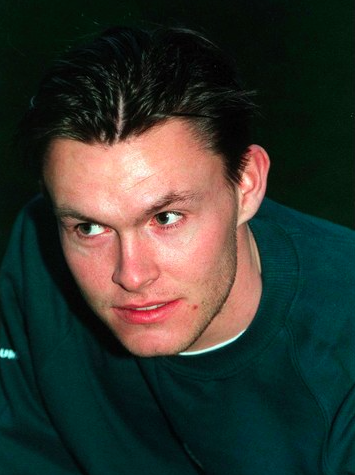

“It seems like a lifetime ago now”, Turner says.

“Youngest goalscorer before Michael Owen took it from me. I’m at number six now. But, to be there alongside names like Wayne Rooney, Cesc Fabregas and James Milner and stuck somewhere between Owen and Raheem Sterling…Everyone remembers those types of players and then there’s me at number six. And everyone is saying, ‘Who’s that?’ You have to smile about that. It’s gone. You have to live your life accordingly, move on and make the best of things. For the cards I was dealt, my career is something to cherish. I could’ve fulfilled a lot more but the Gods were against me. You’ve got to be grateful.”

That season particularly, Turner was the next big thing. It wasn’t customary for teenagers to be playing regularly for high-profile sides in England. Only in exceptional cases, like Ryan Giggs. He was highly-regarded and when it came to the international scene, there was a battle for his involvement.

“I had an approach from the Republic of Ireland and it was a big choice for me”, he says.

“I’d played for England schoolboys, Under-16s and all of that. It was a hard decision and it wasn’t, because the majority of my family were Irish. My Dad’s side is all Irish and there’s loads of us. Also, I had been extremely close to my Granddad and I lost him when I was quite young. He’d always supported me and I’d do everything with him. So there was always that strong Irish connection. As much as I was born in England and I’m proud to be English, there was always the feeling that my Granddad and my family would have liked me to represent that Republic. And because my Granddad never really saw me play football at any level, I wanted to make him proud of me. And I know he would’ve been.”

“Also, I had to be realistic. At the time, I thought, ‘What are the chances of getting a full England cap versus an Ireland cap?’ I was involved with a few senior Irish squads but I never got on the pitch so that’s a bit of a disappointment but to be around with the likes of Roy Keane, Ray Houghton, Paul McGrath and me as a seventeen/eighteen year-old…it was a bit of a dream-come-true scenario. I loved playing for them and it was a very proud moment to represent the Republic of Ireland and all of my family would come to watch. The support I got over there was always immense.”

Although Turner had yet to be capped at underage level, he was selected in an extended senior squad by Jack Charlton for a friendly against Wales in February, 1993. But, a cap never transpired. Turner did appear for the Under-21s and with a World Cup on the horizon, there were whispers that he could be included.

“There is still a chance for some of our youngsters to break through into the senior squad – and Andy could be one of them”, Maurice Setters said at the time.

But, it didn’t happened. And given his age, he was never likely to have been fully trusted by Charlton anyway, though the Ireland boss had suggested Turner as a possible long-term replacement for Tony Galvin

“We’ve never really replaced him”, Charlton lamented in the spring of 1992.

Turner was still living at home with his parents when he announced himself to the Premier League. After the goal against Everton, various news reports outlined how his father, Pat, had also been a promising player at Charlton before injury ended his career.

”I hope that’s not an omen”, Turner said.

It proved a prescient remark.

When Ossie Ardiles arrived as Tottenham boss, Turner’s contributions were severely limited. He went on loan to Wycombe, Doncaster and Huddersfield just to get some minutes. He finally left north London in 1996 and signed for First Division Portsmouth. He enjoyed himself at Fratton Park and it was good to be playing regularly again. The team narrowly missed out on the play-offs and reached the FA Cup quarter-finals. And then, midway through his second campaign, everything changed.

“It was the FA Cup third round. Aston Villa. Fratton Park. We drew 2-2. And I lasted twenty minutes”, Turner begins.

“I never had any trouble with my ankles until about three months beforehand. We were playing Ipswich at Portman Road. I’d received the ball and I’d come inside and ran into the area. I think it was Mauricio Tarrico who went for the tackle and got the ball. But my ankle was planted. And he’s taken that too. After that challenge, I felt it wasn’t right. You just think it was a heavy tackle and you move on. But I think I even missed a few Irish games because of it. It used to flare up and then settle down. And if I could play, I’d just strap it up and get on with it. With hindsight, it was probably more damaged than I thought. But a lot of players are 80% fit and just want to play. So I just carried on.”

Against Villa, Pompey took the lead through Craig Foster after just six minutes. The crowd were energised. They smelt blood. Energy was high.

“Steve Staunton had the ball and passed to Fernando Nelson and I went from one to the other to try and close Nelson down”, Turners remembers.

“And as Nelson passed it back to Staunton, I just heard a gunshot. I thought someone had two-footed me. Honestly, it was just a big bang. I went to run, just instinctively. And it just went from underneath me. The whole ankle. It went floppy. I was walking on the side of my foot because the ankle kept buckling. I didn’t have surgery straightaway because of the swelling and stupidly enough, it would go stable and I’d think, ‘Maybe, I can keep going’. But eventually, a couple of weeks later, I went in for the operation. I remember waking up in the hospital bed and the surgeon came in. ‘Five or six of us had a look, Mr. Turner. It was an accident waiting to happen.’ There’s a groove for the tendons that go underneath the ankle bone. But with me, there was no groove. So the tendons were just sitting there, unprotected. But they told me they’d put everything back together and then the surgeon says, ‘You’ll be able to play again, but I don’t think it will be at the level you’ve been at’”.

I knew at that moment that I wouldn’t be playing top-level football again. All my hopes and aspirations – for club and international football – were over. I was 22. It’s hard to get your head around. It’s the most frustrating thing. You have your entire life ahead of you, you can still play but not at the level where you are. But at that time, you just want to make sure you can walk properly, run properly and can still play the game. So it gave me hope. I wanted to get back to the level I’d been at, but I couldn’t.”

Turner did get back but he was a pale version of himself. Once a flying winger, a rampaging figure who’d hug the touchline and torment various full-backs, he’d lost so much of what had made him stand out. The turn of pace was gone. The movement was restricted. And it was a heavy psychological burden. In his mind, he was still the same player. In his body, he was radically different. It took its toll.

“I was like a broken soul”, he admits.

“Injuries hampered me. When you’re playing and know you’re not right…But, as a professional footballer, you do carry on. Everyone gets injured and it’s not a case of wanting anyone to feel sorry for me. But the ankle was so debilitating in terms of the way I played. The movement and flexion in my left ankle compared to my right is about fifty percent. So, if you want to play football on it, you’re going to have a problem. When you get older, you still know the game perfectly in your mind. But your body can’t do it. That was me at 26 or 27.”

“In your mind, you’re fine. And you’re at a young age. I was 22 in January, ’98. I was getting good treatment, good advice, nurtured well. But when you know in yourself that your mechanics are off…I was very quick. I was always renowned for that. I was explosive, direct, would get the odd goal, set up the odd goal. And I could feel myself lose some of that. I could still play but I wasn’t where I wanted to be. And that’s the frustration. Psychologically, that hurt me. But I wanted to keep going.”

When I came back from the ankle injury, I played a friendly with Bournemouth – just a simple Under-18 or Under-21 practice game. I was warming up and I felt my right knee go. It just clicked and I thought, ‘Oh, shit’. And I never said anything. Because I was that frustrated. I’d spent a year out with the ankle and the first game back in this little friendly, I’d felt the knee pop. So for the next three months, I was treating my knee because I didn’t want anyone to know. To this day, the right knee has always given me problems. Professional footballers get injuries. But I was hampered with them. I’d go and see a psychologist to get me through because of the severity of things and how I felt at the time. I wanted to make sure I was in a good place. Because there were some dark times.”

“I started to go down the ladder. League One, League Two. I wouldn’t say I was disintegrating but my body was just out of balance all the time because I was compensating for the lack of mobility in my ankle.”

Turner went to Crystal Palace and barely featured. But Wolves came calling and, still optimistic, he headed for Molineux.

“The first week at Wolves, I got injured”, he says.

“It was just because of the way my body was. At the end of the season, I said to (manager) Colin Lee, ‘Let me go and play’. I knew I was never going to feature for a Championship side who were going for the Premier League. I was selfish and just wanted to play and I went to Rotherham and did have some fantastic years, including two promotions. But I was always nursing aches and pains all the time. And people don’t know that. It was a real frustration for me, living with that. Psychologically, I was down. I wasn’t beaten. I was just forever challenging myself to physically get through a game. I was meant to be at the optimum performance level but I was always susceptible to a hamstring strain or a calf pull. In the end, something had to give.”

Turner eventually stopped playing at 29 and has been immersed in a coaching career for the last fifteen years, with a particular focus on youth and academy sides. He’s accumulated every type of coaching badge, enjoyed stints at Wolves, Nottingham Forest and Port Vale while he also took charge of non-league sides like Alsager Town and Romulus FC. Earlier this year, he was presented with the opportunity of a lifetime and headed for Dhaka to take charge of the Bangladesh national academy.

“When you step into a different culture, you don’t half look at life in a different way”, he says.

“People live their lives in such different ways and there’s so many emotions attached to that. It’s very humbling. It’s a fantastic place to be. The players here are so honest and football is their life and I’m helping them try and be successful. I was given an opportunity but it was never going to be an easy ride with an injury such as mine. It was frustrating at the time but I always think that everything happens for a reason. I’m immensely grateful for my coaching career and what that has given me.”

People say, ‘Why don’t you speak about your playing days?’ But I’m a humble guy. I don’t talk a lot about it because I was a long time injured and as much as I’m proud and grateful for the opportunity, I feel it wasn’t fulfilled because of circumstance. At 29, when I stopped playing, I was just tired of the niggling injuries. There were times – between injuries – when I felt good but there weren’t enough of them because you were always thinking… But I did have some memorable moments and they can never be taken away from me, can they?”

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!