IN 1997, doctor Larry Nassar was first accused of sexual assault by Larissa Boyce.

At the time, the charges were not taken seriously or picked up for prosecution.

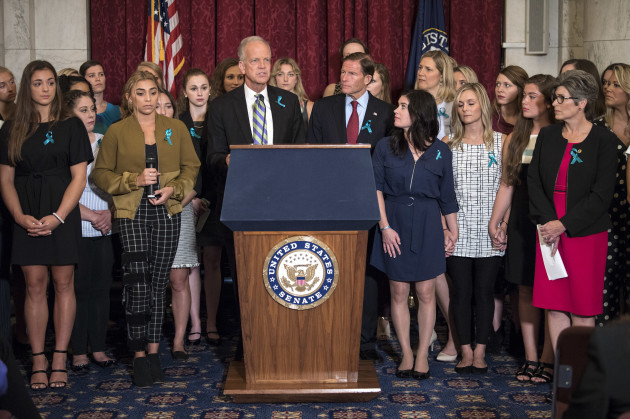

It was not until 24 January 2018 that Nassar was sentenced to 175 years in a Michigan state prison after pleading guilty to seven counts of sexual assault of minors.

Boyce was ultimately one of the many women who made a victim impact statement at the trial.

Nassar had been working as both the USA Gymnastics national team doctor and an osteopathic physician at Michigan State University.

The statistics of his abuse are staggering. As a new Netflix documentary ‘Athlete A’ recounts, over 500 survivors of Nassar have now come forward, including nine Olympians.

‘Athlete A’ is directed by Bonni Cohen and Jon Shenk, who also oversaw Audrie & Daisy, an acclaimed 2016 documentary about three cases of rape of teenage American girls.

The new film, however, is not merely a profile of Nassar. Instead, it focuses on the deeply flawed system in US gymnastics that contributed to the scandal.

The problematic saga is traced back to the early 1980s. Husband-and-wife coaching duo Béla and Márta Károlyi had enjoyed great success with Romania in gymnastics.

They trained Nadia Comăneci, a five-time Olympic gold medallist and the first gymnast to be awarded a perfect score.

The Karolyis lived amid the dictatorship of Nicolae Ceausescu and regularly clashed with Romanian Federation officials.

This tension ultimately resulted in the pair defecting to America, where they helped transform US gymnastics into a powerhouse of the sport.

The plethora of successes they oversaw included nine Olympic champions, 15 world champions, 16 European medallists and six US national champions, leading them to be inducted into the US Gymnastics Hall of Fame in 2000, while Béla made the sport’s international hall of fame three years earlier.

Not long after their arrival in the US, they set up the Karolyi Ranch, a training centre in Sam Houston National Forest, Walker County, Texas.

After Mary Lou Retton — coached by Karolyi — won a gold medal at the 1984 Olympics, interest in the sport increased significantly Stateside.

The success as well as the perceived wholesome image of gymnastics proved attractive to sponsors in America. Karolyi was even paid by McDonald’s to have their logo as part of his sleeve design.

On the back of Retton’s success, the number of students enrolling at the ranch grew significantly to 1,400.

Yet the abundance of glory and sponsorship money came at a cost. Parents were not allowed to attend the ranch. Some gymnasts later accused Béla of emotional and psychological abuse, suggesting they developed eating disorders and low self-esteem as a result.

Emilia Eberle, a Romanian Olympic gymnast, even claimed in a 2008 interview that she was frequently beaten by Bela Karolyi while training at his gymnastic centre in Transylvania.

Although conceding that the environment at the ranch was intense, the Karolyis, who are now retired, have denied all forms of abuse.

Yet it’s been argued by a number of former competitors that a culture of fear and intimidation existed at the Karolyi Ranch that left many athletes afraid to speak out. Only athletes and those close with the coaching team were permitted entry and at one point during ‘Athlete A,’ ex-gymnast Jamie Dantzscher remarks that Nassar was “the only nice adult I could remember being a part of USA Gymnastics staff”.

Of course, many of Nassar’s abuses took place on the ranch, and a baffling attitude towards sex abuse accusations from the USA Gymnastics hierarchy facilitated his crimes and meant he continued working as team doctor with the organisation from 1996 until 2015.

Allegations would be dismissed as ‘hearsay’ unless signed by a victim, a victim’s parent or an eyewitness to the abuse.

Moreover, the documentary also tells the story of Maggie Nichols — considered by many people in the sport to have been behind only Simone Biles in terms of excellence during her peak. She privately reported Nassar in 2015 to US Gymnastics and later, to the surprise of many fans and critics, failed to make the US team for the 2016 Olympics.

One of the chilling end notes to the documentary explains that after Nichols reported Nassar in June 2015: “In the 15 months that elapsed before the Indianapolis Star’s first article on Nassar, he continued to see patients and abused dozens of girls.”

US Gymnastics say they contacted the FBI over the matter, yet it was not until the story became public through the media that significant action was taken.

*****

One of the starting points for the creation of ‘Athlete A’ was ‘Chalked Up: Inside Elite Gymnastics’ Merciless Coaching, Overzealous Parents, Eating Disorders, and Elusive Olympic Dreams,’ a 2008 book by former US champion gymnast Jennifer Sey.

Sey, who also serves as a producer and interviewee in the film, had first-hand experience of the toll that the physically abusive world of US gymnastics takes, with a succession of ankle injuries and struggles with bulimia prompting her premature retirement from the sport in the late ’80s.

The former star saw parallels between her own story and the latter-day controversies, prompting Sey to approach Cohen and Shenk about making a documentary on the broader culture of systemic abuse in the sport.

“From the beginning, we had an ambitious plan for the film, which was to tell the story of how Larry Nassar was exposed, which ends up being quite a long chain of events that involved the Indianapolis Star reporters who had been reporting on USA Gymnastics policy, where they would not necessarily go to the police authorities when they heard about sexual assault,” Shenk tells The42.

“Of course, the survivors who responded to that [first Indianapolis Star] article to inform the reporters Larry Nassar had abused them when they were gymnasts led to the police getting involved and led to prosecution in the state of Michigan and ultimately federal prosecution. We wanted to tell that story with the key players who stepped up in that timeline.

We also wanted to go backwards in time and to explain to the audience how this system evolved to allow a predator like Nassar to thrive and of course show that there were other instances where coaches were abusive.

“That was the notion — we wanted to do several things at once. Really, the final piece we discovered was Maggie Nichols, an Olympic hopeful in 2016. She had this parallel story going on, where she reported Larry Nassar internally to USA Gymnastics, but the information was kind of squelched for mysterious reasons, delayed in the legal process and then she was also left off the Olympic team.

“We wanted to create a film that [explained] all that at once, which at first, was quite overwhelming.”

One of the inspirational elements of the story is the bravery of the survivors willing to confront their troubled past and help ensure justice prevails.

In one moving scene towards the end of the film, the victims are shown in court reading statements to Nassar about the impact his actions had on them.

Many of the survivors also were interviewed for the documentary, as they seek to tell their story in the hope that it will help others.

“We had learned from our previous film ‘Audrie & Daisy’ that survivors of sexual assault often suffer deeply and it takes many years to get a sense that they have the power to tell their own story and push back on either their abuser or the system that allowed for it to happen,” Shenk says.

“And we really communicated to them that we wanted them to feel like they could choose to participate and even when they participated, choose what details they wanted to reveal and what they wanted to keep private.

In general, the people that we profiled in the film really had a great deal of passion for the project. They wanted to tell the story and they wanted the world to know what they had been through.

“Hopefully [it can help] expose a system in a way that could keep this from happening in the future. There was a lot of activist passion on behalf of the survivors in the film and of course the journalists, lawyers, police and legal teams also wanted the public to understand how difficult it was to expose this one man and the system that he operated in.”

As to why it took Nassar more than 20 years to be punished for his crimes, Shenk adds: “What we lay out in the film is the truth behind a system, where unfortunately, the US Gymnastics team or the people who control it anyway are more interested in the sponsorship dollars and the glory of winning than they are necessarily of the health and safety of the athletes that are actually doing the hard work.

“Another reason was that, as is common with many child predators, he had an ability to groom his victims and make them feel comfortable. He figured a way over time that many of these gymnasts were so turned upside down by a system where they were working very hard, they were concerned about the judgement of their coaches and the higher-ups who would ultimately choose them or not choose them for the Olympic team. They felt powerless in many cases to speak up about what was going on.

“So in that context, Nassar was this jolly nice-guy personality who at the time felt like a safe place for the gymnasts. Ironically, he was using this technique of being a goofy nice guy to get closer access to the girls and ultimately abuse them.

But Nassar, of course, wasn’t the only criminal. There have been dozens of coaches in the gymnastics community for decades that have mistreated, and even molested and raped children. The system itself has generally tolerated that unfortunately.

“One of the points we tried to get across in the film is that people like Nassar may be inevitable. Somebody like that arises in society from time to time.

“We need safeguards and policies, so when that does happen, they immediately get rooted out and punished.”

An additional strand of the film highlights the physical abuse athletes often withstand to attain success. Sey cites Kerri Strug’s gold medal at the 1996 Olympics as a classic example.

During the event, Strug landed awkwardly and suffered an injury that turned out to be two badly torn ligaments in her ankle. Yet the 18-year-old American continued competing and ultimately triumphed, leading to the indelible image of Karolyi carrying Strug, who was incapable of standing, off the mat following her victory. The moment was generally perceived as heroic, but Sey considers it problematic and indicative of the immense pain athletes are invariably expected to endure in pursuit of glory.

“When you have an organisation that has thousands of underage children in its membership and you have adults who are overseeing those children, it takes on an extra responsibility — a child doesn’t necessarily have the tools or the perspective to know how to take care of themself,” Shenk adds.

If they have a sprained ankle, a fractured back or whatever injury, they really need experts to tell them when to stop and when to go.

“Bonni and I didn’t have first-hand accounts of this, but if you believe what many of these gymnasts say, they’re told oftentimes to push it, to go further, to perform on the broken back and the sprained ankle.

“Unfortunately, that can lead to lasting physical disabilities throughout the rest of their lives. But they didn’t necessarily have the perspective to know that at the time.”

And on a related note, with many elite gymnasts training at an intense level from as young as 10 years old, Shenk agrees when it’s put to him that the way children are integrated into elite sport needs to be reconsidered.

“One of the things that really attracted me to this film is I’m a big believer in physical activity and I think physical education is as important as any kind of education.

“For people to learn their relationship with their body, how to build strength and stamina, is such an important thing in the development of a young person.

“Oftentimes in the United States and I’m sure it’s true in other countries, the well-being of a child takes second place to a coach or organisation trying to win a game.

In the case of elite sports, of course there are children who are going to excel above the rest, but my opinion is that we should take extra responsibility to oversee that process and make sure that we’re not hurting those children.

“I think many gymnasts would agree that we need to re-think how we guide these children and what we teach them about priorities in their lives.”

Although Nassar is facing life imprisonment, one of the frustrating aspects of the story is that others connected to the crime have yet to be put behind bars.

The Karolyi Ranch was closed in 2018, while USA Gymnastics’ entire board quit in the wake of the scandal, yet there is still a sense that justice has not been fully served.

In the film, ex-USA Gymnastics president Steve Penny is shown invoking the fifth amendment and refusing to answer questions relating to Nassar.

The Karolyis, meanwhile, have denied knowing about Nassar’s abuse, though civil suits filed against them have claimed otherwise.

“Many people who knew about his crimes are still not in prison and have not been tried,” Shenk explains.

“In the United States, we’re waiting on the Justice Department to release a report that they’ve been working on for years now, concerning the FBI’s role in this case, why it took them a year to take any action against Nassar.

“Of course, Steve Penny, who was CEO of USA Gymnastics at the time Nassar was doing his criminal activity, was arrested for tampering with evidence, but the case has kind of languished, we haven’t seen any action on it in the last year or so.

I think Americans have been waiting for justice. There has been some and the survivors have had a great deal of success, but we’re waiting for the other shoe to drop.”

And of course, gymnastics is not the only sport in which allegations of abuse have surfaced, and there will likely be more to come down the line.

“I would hope that the US Olympic Committee and the US government would step up, and for policies that would obligate the federations in charge of elite sports in this country to provide bullet-proof protection for the athletes that it works with,” Shenk concludes.

I don’t think we’ve seen that kind of systemic change yet. There’s certainly a good start with gymnastics and there are a number of survivors in other sports that are now speaking out, which is a good thing, but I also think we have a way to go.

“It’s clear predators seek out situations in which there is minimal oversight.

“So for example, sports in schools, in the United States anyway, are generally team sports and it’s very difficult for a teacher or a coach to be alone with an athlete.

“But in USA Gymnastics, for decades, there were ample opportunities for coaches to be alone with athletes. When they travelled, oftentimes parents were discouraged or even disallowed from travelling with their children. So there are hotel rooms, there are locker rooms in gyms, where parents are discouraged from coming. Many gyms in the past had no policy that disallowed a coach from being alone in a room with an underage athlete.

“And that’s started to change. We’re starting to see new rules where coaches and athletes cannot be alone in a room.

“But in individual sports, there are generally fewer people, fewer adults and other athletes around to provide basic oversight.

“So there was a perfect storm in a way with USA Gymnastics, because their athletes are so young and there was so much opportunity for predators to find vulnerable situations in which they could prey upon the young girls.”

Athlete A is now available to stream on Netflix.