1. Watching Galway win All-Irelands as a Mayo man is like watching the girl you love marry someone else. Watching Galway win All-Irelands as a Mayo man living in Galway is like watching the girl you love marry someone else, the someone else is your best friend, with you as the best man.

Being from Mayo, you think you know pain – the sporting kind – the pain of being good, but not quite good enough to win it all. The pain of being bad, but not quite bad enough to make you quit caring. The pain of hope and the pain of inevitable disappointment. The pain of the perpetual pity.

There’s all that pain, and then there’s the pain of your glamorous, indifferent neighbour coveting the one thing you so desire. It’s a whole other level of pain. You tell yourself it’s better to have loved and lost, but, on those days, when Galway wander up to Dublin and perform the most brutal of eye wipes, you wished you’d never loved at all.

Writing for the Irish Examiner, Colin Sheridan describes the pain as a Mayo man living in Galway this week

2. Already one of the sport’s most popular figures, the rapport between McIlroy and fans this week has somehow been strengthened. His practice rounds were greeted with spirited cheer, his tournament rounds were de facto pep rallies. He not just entertained but galvanized those that followed and they in turn returned the favor. From his Saturday bunker theatrics onward, McIlroy had turned the Home of Golf into a home game, and his opponents had to deal with trying to win the claret jug in front of a gallery that didn’t want to see them do it. When asked if it was clear who the rooting interest was, Scheffler politely pointed out the obvious. “They’re chanting his name out there,” Scheffler said on Saturday. “How can you not root for Rory?”

What Rory was doing was the talk of every conversation in town, and it wasn’t so much a discussion as an acknowledgement of what was destined. It was said in awe and said in reverence. It was said in self-congratulations, observers unable to process the luck of being here to witness something special. On one weekend night a group of well-watered fans walked down a side street, arms over the others’ shoulders, crooning, “Rorrrrr-y, Rory, Rory … RORRRR-Y!” The improvised tune made up for its lack of harmony with joyful inflection. Heading into Sunday, the Open didn’t feel like a competition as much as a coronation, and the people were ready to greet their king.

One problem: No one told Cameron Smith.

Joey Beall explains on Golf Digest that while Rory McIlroy didn’t win the claret jug, he won this Open

3. As soon as Brazilian umpire Carlos Bernardes stepped on to the court on 29 March, he knew it was going to be a difficult morning in the chair. It was the Miami Open 2022 and he’d been assigned the last-16 clash between the young Italian player Jannik Sinner and the Australian Nick Kyrgios. From the start, Kyrgios was on edge, muttering about the slow conditions on court. At 4-4 in the first set, Kyrgios made a good return on Sinner’s serve, only for noise from Bernardes’s walkie-talkie to loudly interrupt play. Bernardes called for the point to be replayed. “You should be fired on the spot,” Kyrgios yelled at him. “How is that possible? How is that possible! The fourth round of Miami, one of the biggest tournaments, and you guys just can’t do your job.”

Unfortunately for Bernardes, that was only the beginning.

For the Guardian, William Ralston goes inside inside the secret world of tennis umpires

4. If big-city columnists or Sports Illustrated feature writers used to be the most prominent jobs in sports media, now it is the insider. Like Adrian Wojnarowski, whose NBA news breaks for ESPN have their own hashtag, or Shams Charania of Stadium and the Athletic, Schefter has ascended to the heights of the job.

But he also has repeatedly demonstrated its pitfalls. In October, emails surfaced that showed he sent the full text of a story to a team executive, a journalism faux pas, asking for feedback and obsequiously calling him “Mr. Editor.” A month later, he reported that Minnesota Vikings running back Dalvin Cook was accusing a woman of domestic violence without relaying the full context of a complicated situation, including that the woman was actually suing Cook, alleging he was abusive. Then, after a Texas grand jury declined to charge star quarterback Deshaun Watson amid sexual assault allegations, Schefter tweeted that Watson had welcomed the case all along because the truth would vindicate him — implying, wrongly, that a grand jury “no-bill” decision meant Watson had been found innocent.

Each incident prompted a public response from Schefter and raised eyebrows at ESPN, where text messages flew between reporters and on-air personalities, wondering how the network’s marquee reporter could be either so careless or so clueless.

Ben Strauss profiles NFL insider Adam Shefter for the Washington Post

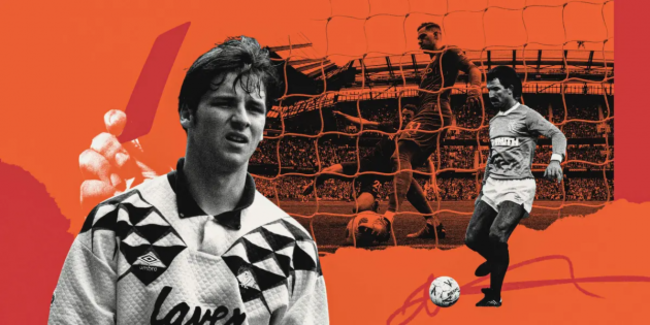

5. “It was the opening game and the first time this rule was ever in effect in an official competition,” Kyle Campbell says, smiling. “I joke with people all the time that, ‘Yeah, I was called for the first backpass violation in history’.”

Campbell is a real estate lawyer in California these days. But back in 1991, he was playing in goal for the United States at the Under-17 World Championship in Italy, where he performed brilliantly and was named in FIFA’s team of the tournament.

Campbell saved a penalty from Alessandro Del Piero in that opening game against the hosts, and Pele presented him with his man of the match award afterwards — a state-of-the-art twin-cassette JVC stereo. Yet the story that he dines out on is handling that first ever backpass.

The Athletic’s Stuart James looks at the success of the backpass ban, 30 years after modern football’s best rule change