LET’S BEGIN IN November 2018.

UK Prime Minister Theresa May has published a draft Brexit agreement with Brussels, and the news pages are filled with Irish people across all walks of life re-assessing their relationship with Britain.

It’s happening on the sports pages too.

Martin O’Neill has been sacked as manager of the Irish senior men’s team, and Emmet Malone of the Irish Times dials up the people’s favourite for the job.

Mick McCarthy is the FAI’s frontrunner but public sentiment lies elsewhere, beside the tastemakers’ doubt.

Can you really command the respect of a dressing room of Irish players based in Britain?

- For more great storytelling and analysis from our award-winning journalists, join the club at The42 Membership today. Click here to find out more >

“I absolutely have no doubt about that”, replies Stephen Kenny. “I actually find the question quite insulting. It could be argued that I haven’t played in England but it could be argued that the majority of the players haven’t played in the group stages of a European competition. Which is more relevant for international football? It could be argued either way, it’s subjective.

“I think it’s a non-argument.”

Kenny ultimately got the job, only the second man to get it having coached in the League of Ireland since 1985. His role is the figurehead job in Irish football, and though he saw direct comparison to British football as a non-argument, that dynamic has been the propulsive force through Irish football for decades: Irish football has been dwarfed by Britain to the point of being defined by it. His appointment signalled something different, but has he ultimately been at the vanguard of a great change?

On the eve of his first game, Kenny boldly declared to the media his primary ambition as Ireland manager: to break from a “British style.”

**********

The National League

It’s not just a case that English football has overshadowed Ireland’s domestic league: it even paid for the lights that cast the shadows.

Sunday afternoons were the preserve of League of Ireland games until Sky Sports muscled Premier League’s Super Sundays onto that terrain, and now-archaic Uefa rules meant they had to compensate the overseas territories within its purview. Hence £1.5 million was secured to install floodlights across Irish grounds so games could be moved to Friday nights.

In truth, the horse had long-since bolted.

As Daire Whelan writes in Who Stole Our Game? The Fall and Fall of Irish Soccer, crowds fell precipitously from the 1960s onwards, when Match of the Day came on air and ITV began beaming Sunday afternoon games on The Big Match.

“It was these broadcasts that many in the League of Ireland point to as the beginning of the real decline”, writes Whelan, and John Giles captures the former age in his autobiography, contrasting his heroes in English football with the Drumcondra players he watched in the flesh.

“They lived in my imagination, in another country, but I could actually see my Irish heroes for real.”

Television ultimately took these heroes out of the imagination.

Even paying appropriate reference to Irish football’s dysfunctional masters, renowned football writer David Goldblatt is fatalistic about any substantial growth of the League of Ireland.

“Allowing for the incompetence of the FAI and the Irish government and their inability to reform its youth development systems”, writes Goldblatt in The Age of Football, “Irish football never really had a chance. The explosive global growth and magnetic appeal of its giant and very accessible English neighbour was unstoppable.”

The crowds are not just watching on television. Research showed that of the 800,000 visits from overseas to Britain that included a football match in 2015, 121,000 were made by Irish people.

“Ireland’s intimate engagement with English football began the moment the British state left the country”, writes Goldblatt, “for one of the main consequences of Irish independence was a large wave of migration to Britain but especially England in the inter-war and post-war eras. This established huge Irish communities in London, Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool. Many of them gravitated to Arsenal (known as the London Irish), Aston Villa (who now sell more shirts in Dublin than in any other city), and Manchester United and Everton.”

Professor Mike Cronin has written widely on the history of Ireland and Irish sport, and his books include The GAA: A People’s History and Ireland: A History, while he co-edited a collection of academic essays titled Sport and Postcolonialism.

“On the idea of some kind of breaking off, or decolonising moment, and to reduce it to slightly simplistic terms as to what is happening across the African continent and Indian subcontinent in the 1940s and 1950s, you have moments of British withdrawal and nations like India, Bangladesh and Pakistan have to define and build themselves when Britain is gone”, he tells The42.

“The radical difference here is that the decolonising moment in Ireland is incomplete. This is a larger argument but Ireland, in many ways, never had a pure postcolonial moment because it couldn’t ignore Britain. Because it traded with it and people emigrated to it; the flow of information and people means it’s wedded to it. And huge swathes of the population were aware of it, by virtue of the newspapers they read and the radio they listened to. After independence, the Irish papers didn’t say, ‘Right, we’re done with English coverage.’

“So I don’t think it’s a colonial legacy, it’s more of a media legacy. What is a person’s reference point here as they journey through football? It’s English football. It’s Sky and Match of the Day.

“There’s a lot of TV football but the most-watched here is English, so when kids are running around in the playgrounds, who are they in their heads? A Premier League player. It might be a global figure, but their sense of how football is played is in reference to the English league.”

That proximity and the ubiquity of media coverage, according to Cronin, has meant comparisons to League of Ireland were inevitable and then inevitably unflattering.

“The difficult thing is a perception issue: because of this huge thing next door, everybody in Ireland is constantly growing up with this idea that if they go to a League of Ireland game, they are watching something a bit second-rate.”

Is anything changing now?

With the Premier League growing to the point it’s now the proxy battleground of corporations and nation states, with media coverage as pervasive as ever, the shadow is still being cast. In fact, it’s broadened to swallow most of the world.

What is changing is how some Irish clubs are now engaging with it: by making a virtue of the differences.

Daniel Lambert is Chief Operating Officer of Bohemians, a fully fan-owned club that has emerged from the brink of bankruptcy a decade ago to a membership base now almost four times its historic average.

“The Premier League has totally ruled in Ireland and there’s a consistent media spotlight on it, and there’s been a temptation there for clubs and club owners to be a mini-Championship or Premier League club”, he tells The42.

“But these are not successful models, they don’t work. And the ones that do work do so solely because of TV money and massive transfer fees, neither of which exist in our market. Trying to emulate these clubs because that’s what members of the public are used to isn’t sustainable.”

In 2018, Bohs commissioned and produced “Terraces, not TV”, a short video still among the most-watched pieces of League of Ireland media. It’s 75 seconds long and features all of three seconds’ worth of football.

The lesson: stress the club part of ‘football club.’

Copy

“The quality [in the League of Ireland] is pretty good but it’s never going to compete with the Premier League. Once you accept that and ask how you can engage people, you can engage them on a number of levels where football’s a hook.

There are no goals in that video, it’s just about a parent and a kid spending time together. It focuses on those social, deeper messages. People are now in more transient situations: things are changing a lot, you might not get to know your neighbours or colleagues as well as you would have years ago. But a football club can provide that. That’s more of an emotional connection, and if you can engage people on an emotional level rather than on an entertainment level you have a much better chance of keeping people for longer and keeping them engaged.

“Clubs are doing more to engage people on issues. You’ve seen clubs recently engage on gambling sponsorship, for instance, and that’s important. Every club does work in the community, but I suppose it’s about trying to engage people on issues that are important to them. Say the work we do with Focus Ireland. Homelessness is such a massive issue in Dublin and in Ireland. By doing more work in people’s areas on issues that affect their area is reflecting back to people the things that are challenging in their lives and with which they can assist.”

An inspiration in making Bohemians a “focal point” of their community, says Lambert, is closer to home. “You can learn so much from the GAA. It’s such a successful organisation, and what GAA clubs are, for the most part, are the hubs of communities. I grew up playing for Na Fianna and you felt it was one of the glues growing up. League of Ireland clubs can learn from that. A League of Ireland club shouldn’t be a group of people going to a match away every fortnight, it should be something that’s part of you, that you identify with.

But as Damien Duff bluntly put it last year, there are ugly comparisons to be made here too. “League of Ireland facilities across the board, Premier and First Division, are horrific when you compare them to Gaelic”, said Duff on his unveiling as Shelbourne manager.

But if the colonial legacy is not evident in Irish football (bar, obviously, the fact the game has been played here in the first place) it’s seen in the competition.

“The real colonial legacy is the GAA”, says Cronin. “In a way the FAI and the clubs have always had that problem. I am not saying there are not good clubs and youth academies here, there are. But the weight of what they are fighting is enormous.

“The GAA doesn’t pay players, it recycles 80% of its profits, and down the country some of the facilities are crazy, in a good way. If we were to pause the GAA where they are at the start of 2022, and if the FAI wanted to build an infrastructure across the country to compete with the GAA’s across 2,000 parishes, in terms of facilities, the sum of money required would be eye-watering.”

If every domestic league in the world is now reckoning with the gargantuan English game, the Irish game has always done so. It has been doing it in an utterly unique set of circumstances, but at least now there are some unique responses.

*********

Youth Development

Four years ago, a group of Irish academy coaches visited Juventus and were told that Ireland was one of just four countries in Europe in which the Italian club did not have a scout. When asked why that was the case they were told that, in Juventus’ eyes, the world stopped at England.

It’s a remarkable assertion for a club with whom Liam Brady is synonymous, but then consider the fact that, when working as the head of the Arsenal academy, Brady said on RTÉ that Irish football should be grateful to English clubs for developing their players.

So Juventus are not entirely wrong: the world usually did stop at England.

The well-tread path for players was to leave Ireland by the age of 16 and join a top-division academy in Britain, and, in terms of yielding international-standard players for Ireland, it worked quite well for a time. But then the time changed and the money grew and the world shrank.

“In footballing terms Ireland has historically functioned as a Home Nation”, says Cronin. “Therefore the idea of Irish kids going off to live in Manchester in digs at a young age was very much normal.

“Ireland did produce talent, and when that talent was measured against that home-nation mentality, then the Irish players were highly-ranked.English clubs weren’t sitting there thinking, ‘Oh, this mercurial Frenchman is interesting.’ Because that wasn’t happening. The key question to my mind: have Irish players now got worse, or are they just being pushed down? I think they are just being pushed down.”

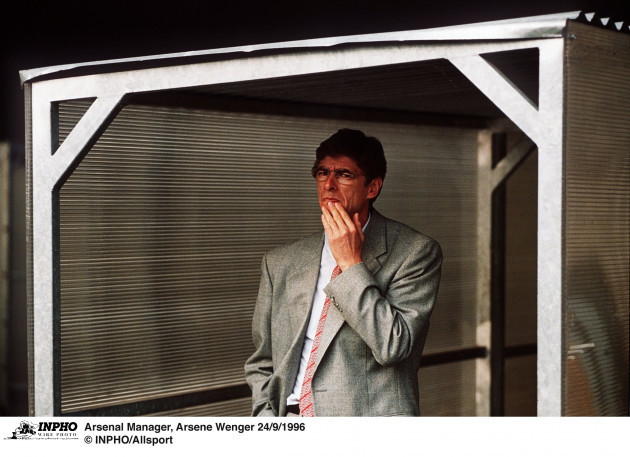

Arsene Wenger was not quite the Premier League’s first manager from outside Britain and Ireland but he was the first truly influential one, building his initial success on European concepts of diet and preparation along with a far wider scouting network across Europe.

Wenger joined Arsenal in the 96/97 season, a season in which 34 Irish players appeared in the Premier League. On a table of represented nations that season, that was second only to England with Scotland third and Wales fourth. Ireland didn’t fall out of the top four of this table until the 2016/17 season and are now seventh, with 20 Irish players appearing at least once in this season’s Premier League.

The number of Irish players represented has fallen and their importance in the league has collapsed: in that 96/97 season, Irish players accumulated 44,338 minutes of action, and last season that figure was almost exactly halved.

To give a further indication of how things have changed: France, Spain, Brazil, and Portugal are all ahead of Ireland in terms of representation in the Premier League this season, along with England and Scotland.

But the flow of players continued despite the diminishing representation. A Fifa report last year revealed a startling statistic: between 2011 and 2020, the country responsible for the highest number of U18 footballers transferred abroad – in absolute terms – was the Republic of Ireland. The vast majority of these transfers were to Britain.

But then along came Brexit.

In the context of how Irish football’s relationship with Britain is changing, there is nowhere more obvious than the realm of youth development because that’s where the rules have changed.

As per EU rules, players can transfer to clubs in other countries from the age of 16, but as soon as Britain left the Union, the rules changed to forbid players from Ireland or elsewhere in Europe from moving to the UK until their 18th birthday.

Irish players can still move to other EU countries from the age of 16, so there are now two options for the teenagers no longer able to go to Britain: stay in Ireland for longer, or move to mainland Europe.

Many have stayed for longer and as a result, the League of Ireland is getting younger. The average age of a player in the Premier Division has dropped by three years in the space of three seasons. Last year it was 25.4, down from from 28.4 in 2018. (When compared to the most recent top division season across other European nations, only the leagues of Croatia, Austria, Latvia, Montenegro, Netherlands, North Macedonia, Slovakia, and Denmark had a lower average age.)

And while Juventus have not been scouting Ireland, the rest of Europe are beginning to catch on. As St Patrick’s Athletic’s Academy Director Ger O’Brien recently told The Athletic, “European clubs are saying; ‘Hang on, the Aaron Connollys and Adam Idahs can’t go to the UK at 16 anymore. The talent must still be there. Let’s go and find it’.

“I’m now dealing with fellas from France, Italy, trying to get people on the ground here to give them information. For clubs in Belgium or Germany, Ireland is an untapped market. If you’re a German club on the border with Austria you’re probably fishing in Austria or Hungary; but now they’re also thinking of Ireland.”

These moves are happening. Cathal Heffernan of Cork City has been on trial at Bayer Leverkusen and AC Milan of late, Roma have expressed an interest in Justin Ferizaj of Shamrock Rovers, while Pat’s this week sold James Abankwah to Udinese, who will join their first team next summer and likely become the first Irish player to appear in Serie A since Robbie Keane did so for Inter Milan. Irish clubs are also hoping a broader market may also lead to an increase in transfer fees, which have historically been pitiful. To pluck one example, the $700,000 paid to League of Ireland clubs in 2020 was a third of what the Georgian league brought in.

Here’s an example of how things are changing.

Inter Milan did not have to pay a transfer fee to Shamrock Rovers when signing Irish U17 international Kevin Zefi as he had not signed a professional contract, so were only liable for the quite minimal, Fifa-mandated compensation to Rovers and his earlier club, St Kevin’s Boys.

Inter, however, volunteered to include several performance-based add-ons payable to Rovers if Zefi progresses through the ranks, at least partly to keep Rovers sweet in the knowledge this may not be the last time they work together.

Some Academy sources in Ireland believe some UK clubs – though not all, it has to be stressed – often recruited Irish players simply for the sake of it, to pad out their youth teams to serve their biggest talents and to maintain grants and funding which demanded clubs run a youth training scheme.

(That’s not to suggest that this is the single factor in earning higher fees in Ireland: signing players to better-remunerated, longer-term contracts without a low release clause is the key move in that respect. Players moving to Europe at 16 also risks the continuation of the painful age-old trend in Irish football of young players not signing a professional contract and thus leaving for no transfer fee. Some Irish academies have suggested introducing here a law change enacted in Belgium, whereby players can be signed to pro contracts at the earlier age of 15.)

Paradoxically, Brexit has made it easier for Irish players aged 18 or over to move to Britain, as the Common Travel Area makes Irish players exempt from the UK’s point-based work permit system, so their opportunities in the UK have actually increased. Premier League clubs can no longer scour the four corners of the world for young talent yet to make a breakthrough at international level, so for Irish players, suddenly the market has shrunk a little.

The ultimate ramifications of Brexit on Irish football will take years to crystallise, but there’s already been significant change, best encapsulated by the team-sheet for last November’s U17 international against Andorra. For the first time in living memory, not one of those Irish players was signed to an English club.

There’s some way left to travel, mind.

Juventus still haven’t employed an Irish scout.

*********

The National Team

And so back to Stephen Kenny and the national team.

Styles of play are difficult to quantify without getting utterly lost in statistics, but any fair-minded observer would have to acknowledge the team are playing more progressively and they are now scoring goals at a rate they haven’t in years. (The 20 goals scored last year was more than the previous three years combined.)

The extent to which concepts of Britishness have cropped up over Kenny’s reign have been almost comical. The managers of Portugal and Luxembourg both referred to Ireland as a “British team” last year, one fecklessly and the latter entirely deliberately, earning a post-game rebuke from Kenny for insinuating past generations of Irish players were playing “caveman football.”

Then there was the motivational video shown ahead of a friendly defeat to England, which led to Kenny answering questions from his employer after a vastly overheated public controversy.

(An exaggerated example, but the extent of Irish football’s entanglement with Britain might be evident in the fact that Kenny was somehow the lightning rod for fulminations on Anglo-Irish relations on the same week that Irish rugby team were captained by a descendant of an Easter 1916 rebel at Twickenham and Croke Park commemorated the centenary of Bloody Sunday.)

The composition of Kenny’s squad has changed, reflecting changes in the country. Now the descendants of emigrants play with the sons of immigrants: London-born Josh Cullen is the fulcrum of the midfield; Chiedozie Ogbene has become the first African-born player to play and score at senior level for Ireland.

Kenny has tightened ties with the League of Ireland as well. When Jack Byrne was introduced to a Nations League game away to Wales in 2020, he became the first domestic player to play competitively at senior international level for Ireland since his namesake Pat did so back in 1985. That game was the last of Eoin Hand’s reign, before Jack Charlton took charge and took the country to states of bliss never before imagined.

The senior men’s team spent decades maintaining the lineage to Charlton, but Kenny – who infamously once said he didn’t go to see Jack’s Ireland as he didn’t like the style of play – now has a management team that doesn’t feature someone capped by Charlton, which hasn’t been the case since Mick McCarthy was first appointed manager in 1996.

That’s not to say the British influence has been completely excised. Anthony Barry’s addition to the coaching staff has been a revelation, and he is a man who spent his entire playing career in Britain, was educated on the FA’s Pro Licence and is now at Chelsea, working with Thomas Tuchel.

That imperceptible flow of influence from Britain will always remain, and Irish football would be poorer without it. (The two winning managers in last year’s League of Ireland season for instance, Stephens Bradley and O’Donnell, were both educated among Arsenal’s youth ranks.)

More obviously, the FAI is now led by an English CEO, Jonathan Hill, who has been appointed in the wake of the chaos of Delaney’s Fall and has made a virtue of the fact he arrived in the job with “no baggage.”

There is also very obvious collaboration with Britain ongoing, as the FAI and the UK’s associations size up whether to bid to host the 2030 World Cup or the 2028 Euros.

“I think it’s a moment of reality that has come in on us in the last few years”, says Mike Cronin.

“Stephen Kenny isn’t saying everything is bad. He is just accepting that this thing next door is so big and so different, and that our space in it is different, that we have to recalibrate that relationship.”

The world has loosened the old bonds and Irish football is shuffling cumbrously to look in another direction. As to where the final destination is and how far that is from Britain is not known now and won’t be known for years.

The FAI will publish a strategic plan stretching up to 2025 on Monday week, and it is imperative they provide a medium-term vision for the domestic league and youth development that is buttressed by concrete, actionable proposals.

One thing is not in doubt, however: great winds of change are blowing across Irish football. Much has changed, and there is much more change yet to come.

Let’s see where it all ends.

For more great storytelling and analysis from our award-winning journalists, join the club at The42 Membership today. Click here to find out more >