IT’S NOT OFTEN you hear about a GAA player being forced to retire due to concussion.

What about a GAA player being forced to retire at the tender age of 20 after six concussions?

Four of those by 18, and two in the space of just over three months as an up-and-coming, prodigiously talented Roscommon U20 footballer.

That’s surely been unheard of.

Until now.

***

Conor Shanagher is more than happy to open up and share his story. To take a look back through the years and track exactly how it all came to this point, to relive the exhilarating highs and the gut-wrenching lows and to, of course, raise awareness of an injury that’s often swept under the carpet in the GAA.

This week, three short posts appeared on the internet under the collective title of ‘Mn329 Conor’s Blogs’ — and within, a story no one would have expected. In his own words, Shanagher penned his heartbreaking, and truly terrifying, story for a college assignment.

He detailed how he “froze” just two weeks ago when he was given “the worst news imaginable” and a top neurologist strongly advised him to hang up his boots and step away from contact sport.

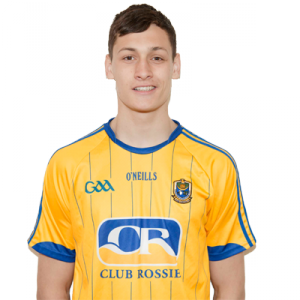

20-year-old Shanagher, a student of Maynooth University and of the Kilbride club in Roscommon, is wise beyond his years though. He radiates this impression of profound maturity and sensibility, this sense of appreciation for what he has — rather than what he has lost — and is confident that his decision is the right one.

“Your health is more important than a game of football at the end of the day,” he tells The42, more than happy to pick up the phone for a lengthy chat on a Friday afternoon.

“It could be a lot worse. It’s obviously not ideal but it’s a lot better than it could be.”

One can’t help but hang on to his every word as he candidly shares his personal experience. Evidently, it’s still raw but he wants to do this for others. To raise awareness of the injury and its severity, and to help anyone in a similar position.

“Concussion isn’t talked about in GAA circles at all,” he points out. “It’s just like you get on with it.

“People still aren’t really believing that it’s actually an injury. It’s like it’s a setback for three weeks and then you’re back again. No one really looks at how damaging it can be, especially after a few of them.

“The GAA just haven’t caught up in terms of dealing with concussion. Because it’s an amateur sport, concussion isn’t dealt with the way it should be.

“I don’t know, by writing the piece it might show how serious concussions can be overall. It mightn’t damage you now but it’s down the line….”

One thing’s for sure: this man knows exactly how damaging concussion can be, and that it’s far from just a bad headache, as many often think.

***

Shanagher recalls his first concussion as well as his last. It came in a rugby game, aged just 15 in his Junior Cert Year at school. Growing up, he played plenty of rugby and hurling but later in life, decided to focus on his beloved Gaelic football.

He doesn’t remember the specific moment or incident in the schools’ match now, but what he does remember is the headache after: it wasn’t a normal one.

“I have to go home, there’s no way I’m staying in for evening study,” he thought to himself as he tried to comprehend what exactly was going on. After resting for the evening and sleeping through the night, it had cleared up by the following morning.

But a quick visit to the doctors was still on the cards. Precautionary more than anything, it was all very relaxed, he assures. The usual tests were done, Shanagher was told to take three weeks off from sport and he was sent on his way.

He followed those orders and carried on, just delighted not to have to endure the pain in his head he had had any further.

But that didn’t exactly last long.

The next two came in Transition Year and Fifth Year, and the horrific headaches returned to haunt him. He was hit with a fourth in Leaving Cert Year in a schools’ Gaelic football match.

Four concussions by 18, shocking really. And they were worsening each time: “My first concussion, I just had it for the evening. My fourth one, I had it for a full 24 hours.”

Each time though, he became more and more accustomed with what he had to do afterwards. He learned how to deal with the symptoms as best as he could, took the three weeks off and returned gradually.

But then came a hiatus; a period of remission, if you like. He completed his Leaving Cert, and secured a place in Maynooth University, where he’s now in Final Year studying Arts, majoring in Business Management.

He was back playing football, and at the highest possible level. He continued to represent his club Kilbride and Roscommon teams all the way up to U20, with whom he lined out with this summer. Things were well and truly going to plan.

Until Saturday 9 June, anyway.

The venue was Tuam Stadium, the opposition Galway and a spot in the Connacht final at stake. This was massive. But then, it happened. Again.

“Ten minutes into the game, I went in for a tackle and actually ended up running into my own player,” the midfielder laughs, “funnily enough!

“We both kind of went for one Galway lad to tackle him. He just ducked out of the way. The lad came in — he’s a bit smaller than me — under my chin. That’s all I remember, just going for the tackle.

“I was unconscious for three minutes and then when I came around, I was fairly confused. I still knew where I was, what year it was; all the main questions.”

He felt relatively okay, despite being stretchered off, and that was the number one priority. Thankfully, there was no headache and this made the fact that the Rossies — real underdogs for this one — were winning well, all the sweeter for Shanagher as he watched on.

Because he had been knocked out and unresponsive though, he was soon bundled into an ambulance and brought to University Hospital Galway.

“I was listening to the game all the way in the ambulance. We ended up winning, which was huge,” he grins down the phone, meaning a provincial final the following Sunday.

“All I was thinking was, ‘Am I going to make it?’ In the back of my head, I knew I probably wasn’t going to but at the same time, because I was knocked out, I hadn’t the headache straight away.”

The hospital visit threw up the standard procedure; the usual questioning of, ‘Do you have a headache?’ ‘Have you gotten sick?’ and other precautionary measures taken.

After waiting six long hours to see a doctor, he was sent home and told to monitor it: if it gets worse, come back in. The next day, he felt fine. A glimmer of hope that he might make it.

“I was fine then until the Tuesday,” he explains. “I did a light session with just the physio to see if I would pass it, but the exercise just brought on the headache.”

And as the team gathered for training and their final preparations on Thursday, Shanagher was ruled out. He wasn’t named in the programme, couldn’t tog.

That was the story then which was really annoying because I was joint-captain or whatever. It was at home in the Hyde and to miss it was obviously the last thing that I wanted,” he continues, his maturity shining through.

“But I knew I was concussed and there was not point in playing six days after it happened. You have to listen to the doctors. Up until the Tuesday I was fully convinced that I had no symptoms of concussion, even though it was in the back of my head that I was out cold.

“Because it was such a big collision, concussion can take a few days to actually hit you. They told me that — ‘You might feel fine now but we have to monitor you all throughout the week because it might just hit you.’

“I was thinking that it never happened before, surely it won’t. But obviously it did.”

A 16-point defeat to Mayo followed, ending the Roscommon young guns’ year but giving Shanagher all the recovery time he needed before club championship kicked off. As he says himself, he was in no panic to get back. He knew how serious things were.

Seven weeks or so after, his baseline score was down to where it should be and he went back playing with the club. Back to business as usual, he got through a few games unscathed and continued to ride the crest of the wave through the group stages of championship.

Pulling the strings from centre-half forward, Shanagher was pivotal as Kilbride topped their group and sealed a quarter-final date with Oran. And then disaster struck once again.

On Sunday, 23 September.

“I remember going for a kick-out, there were a load of people around. Then I just remember the physio saying, ‘Can you count to ten?’

“I got up, I felt fine and wanted to play on. You’re kind of just focused on the match even though you were knocked out. I played on for I’d say a minute. We were getting well-bet at the time anyway so the manager was like, ‘Right, come on off.’”

Similarly to the last time, he felt fine as he watched the rest of the match. He stayed on to watch some of the senior quarter-final but then, it came.

“Into the first half of the match, the headaches really started to kick in. Straight away. Nothing too bad but at the same time, just an annoying headache.

It’s just like a constant tightness. Like an elastic band around your head, pulling up over your eyes. You just feel like your face is being hit.”

That night, he was due back up in Maynooth as his Final Year lectures started the following morning. Up he went, regardless, hoping the pain in his head would pass.

“I got up there and that was it then, I just knew it was bad. I had zero energy, I couldn’t do anything. I could only lie down in bed. Light and all that would annoy my eyes and make the headaches worse.

“It was crazy. I went to bed at like nine o’clock and I woke up at 10 o’clock the next day, I went in to one lecture at 11 o’clock. It’s a 10-15 minute walk to college, so I walked for say half-an-hour, and I came home and slept for three hours.

Well done to the @RoscommonGAA U20's who have defeated Galway by 1-11 to 0-11. They play Mayo before the senior Final at 1pm on the 17th in Dr Hyde Park. Best wishes to Conor Shanagher who suffered a first half head injury. Hopefully he'll be back for the final. #RosGAA pic.twitter.com/hDv9UkuzqK

— Kilbride GAA (@gaakilbride) June 9, 2018

“I was just sleeping and sleeping and I didn’t want to move off the couch all day. The lads in the house were like, ‘What is going on? He wouldn’t wake up, he was so tired and how would you not hear us coming in and out of the house?’”

His mother was obviously worried, texting him through Sunday evening and Monday to see if there was any improvement. But no, things were only getting worse.

“Tuesday, I was like, ‘No this is bad. I have to go home and see the doctor,’” he says, explaining the other symptoms on top of the extreme fatigue, lack of energy and headaches. He couldn’t concentrate, and God forbid he looked at a screen.

“If you were looking at anything, the headache would just get worse. Your eyes would be watery from focusing.

“Your memory is really slow, even responding to people asking questions. It just takes it out of you. You’ve no urgency, everything’s just so relaxed. Everything is such an effort.”

And of course, the bad form and terrible mood. With everyone having just returned to college for the year ahead, the house was busy with visitors in and out and what not.

“I was just in no form for anything. I obviously had to go home to see the doctor, but just being in that environment and me getting annoyed with the lads for doing nothing, I knew something was up and I had to get out of there.”

His Mam came up to collect him on the Tuesday night, and the hazy blur of life as he knew it now, continued on the drive home.

“I just remember I slept the whole way home in the car even though I hadn’t done anything that day. That’s when I knew it was going to be really, really bad. I had never been that bad with any concussion.”

The next morning, he went to the physio and the tests confirmed how bad this concussion — the sixth — was. He knew himself. “Oh Jesus, this is not good,” he thought as he stood on the pressure pad and his balance and co-ordination was examined.

From there, he was sent to Dr Daly, the Roscommon team doctor who had treated all of his sporting injuries through the years. But this Friday morning felt a little different.

“He did the usual and was like, ‘Yeah, you’ve had how many concussions in the last while… two within the last three months? I need to get a second opinion on this.’

“He didn’t really say much, but he was kind of hinting at me that football could be over. He kind of said, ‘It’s not my place to tell you that you need to stop playing.’

“It meant nothing at the time but when I started overthinking it, I was like, ‘Well, he wouldn’t have said that if he wasn’t meaning it.’”

Denial was in full flow, Shanagher admits, as he was referred to Dr Colin Doherty, a neurologist in St James’ Private Clinic in Dublin. As he waited for that appointment, he relocated back to Maynooth but didn’t actually attend any lectures.

“I was still suffering with the headaches but it was better to keep myself busy than to stay at home [in Roscommon]. If you were staying at home, you’d just watch Netflix and I couldn’t even do that without getting headaches.

“It was grand because it stopped me overthinking the whole situation at the same time, and I was distracting myself.”

In the meantime, he had an MRI scan done so when he got to James’, those results were the first thing on the agenda. Given the all-clear with no immediate brain trauma and the most complex organ in the body appearing fine, he could breathe a sigh of relief on that front anyway.

Then came the questioning, the cognitive tests and the memory tests; the theory and the practice, which he failed miserably. For example, he was asked to name as many random items in a picture as he could in 60 seconds. Or as many words beginning with the letter C.

“I would have struggled to remember the names or to get the word out of my head,” he concedes. “It kind of brought me back a few steps.

I knew how slow I was then… at thinking… which is scary. Put me under pressure, my reaction times were shocking. It was kind of scary. I felt dumb in there, I literally couldn’t think of anything.”

His awareness was just as bad, and Dr Doherty soon concluded how shockingly bad this concussion really was. He was nowhere near his baseline — “it’s six weeks on, we need to see you again in a couple of weeks.” Enough said.

But Shanagher wanted more answers there and then.

“I was asking him, ‘Well what’s the story? Is it three weeks after the concussion, like the normal protocol?’ Then he started saying, ‘If I were you, I probably wouldn’t go back.’

“At the same time, because I had another meeting in four weeks, I was kind of thinking, ‘Ah he’s only saying that now to cover himself.’

It hadn’t sunk in. I was just denying it, thinking, ‘This isn’t really happening, it’s all going to work itself out over time.’ It had like; everything went back to normal with all the other concussions. Why would this one be any different?”

Over the next four weeks, he got back to lectures and started catching up on all the college work he had missed. He was pretty much back to feeling somewhat normal.

“The headaches had gone, I’d say around week six after the concussion. It took me that long to get back to normal, not sleeping all the time and actually having energy to get up, go to college and do college work.”

And then it was back into the capital. D-Day, if you like.

They ran through the exact same tests, and there was a vast improvement all round. Clearly symptom-free, his responses and reactions were much, much quicker and his memory had improved ten-fold.

“You’re back to baseline, this is where your three-week return-to-play protocol starts….” he was told. But Shanagher knew that there was a catch. He was waiting for bad news.

“I have to tell you now though, if I were you at the minute, I’d stop.”

And then it was all a bit of a blur.

I froze. It was kind of just like, ‘What do I do?’”

Dr Doherty continued: “It’s only going to get worse. It’s clear to say that with every concussion, the smaller collision led to a longer recovery period. The brain doesn’t recover like a muscle or like a leg-break. You have to mind it.

“He talked about how, down the line at like 30, 35, all the mental health issues that arise from repeated concussion and head traumas. He gave examples of depression and dementia.

I was kind of just shocked listening to him but at the same time I was like, ‘Does this actually really happen?’

“Mam was obviously asking questions like, ‘Ah, if he takes the year off will that make any difference?’ He was like, ‘No. This is the damage you’ve done, nothing’s going to stop or make it any better.’

“He literally said change the way you play, or change the sport you play.”

Shanagher knew that there was no way around changing things in GAA. You simply can’t avoid the tackle, and especially not at the level he was playing at.

But as he thought more and more and came to terms with the news he had just heard, he accepted the recommendation.

“To be honest, the six weeks were definitely torture. He was like, ‘Do you want to go through that again? Is it worth training all winter now to get in one tiny collision and have to go through that for the next six to eight weeks again?’

“That put another dimension to it. Like what would happen if it was next spring and I missed eight weeks of college before my final exams?

That kind of made my decision for me. Football’s great or whatever but at the same time, is it really worth going through all of that for the sake of it?”

His mature and positive outlook on the entire situation must be commended time and time again. But Shanagher is reluctant to bask in praise, or similarly, to accept sympathy or pity of any sort.

He’d rather get up and get on with it than lick his wounds. As he mentioned in his blog, he’ll continue as an active member in his GAA community, stay involved in any capacity possible, and has aspirations to coach in the future.

“I suppose I have no option really,” he smiles. “I don’t know anything else except sport.

“It’s not as if I’m going to completely walk away from it. I’ll still be able to train after a while, just not the contact side of it. It’s not like I’m going to just throw in the towel and say, ‘Right that’s it, I’m never going down to the GAA pitch again.’”

He’s been keeping himself ticking over in the gym and hoping that down the line, he might get into another sport or something that will fill the void that’s there at present.

“That makes it not bad at all really, when you know you can still do a lot of things,” he adds. “There’s no real pain.

Jesus God forbid you got paralysed or something… It’s not like my life is any different now. It’s obviously not ideal but it’s a lot better than it could be.”

The endless support from his family and friends — from the lads in the house in Maynooth to his club and county team-mates, his Mother who’s been there every step of the way to his father, who’s delighted to see his son write and speak openly on the issue as is done in the AFL and NFL — has been huge, and really helped him.

“It’s weird,” he grins, when his family is mentioned. “Obviously, they’ve put so much time into me bringing me to training and whatever over the years.

“They don’t want to see me throw in the towel either but then they’re like, ‘Here we’re not going to another game to see you lying face down in the ground, not knowing what’s going on — then coming home and [Conor] being in the worst mood ever for a couple of weeks.

“It’s completely up to me at the end of the day. Nobody can actually stop me, the doctor can’t actually stop me from playing football. It’s my decision and they’re just fully behind me, whatever I do. That made it easier.

Anyone I talk to, they all say the same thing: your health is more important than a game of football at the end of the day.”

In retrospect, Shanagher agrees that concussion has pretty much stopped his life in the past. Those periods are a complete blur, and as he says himself, he ‘didn’t even know what was going on for three or four weeks.’

He’s well aware now of what’s going on now, and is content with his decision and the fact that he’s accepted it.

“Anyway, the worst part of it’s over so. It could be a lot worse,” he concludes. That said, he knows that there are tougher times around the corner.

“It’s fine this time of year, but say next February, March when the long evenings kick in and everyone’s out playing football, that’s when it’s really going to hit hard.

I’m going to have to just deal with it. Kicking a ball, I’ll be fine. I’ll keep myself busy and then after that, it’ll all be fine.”

It will all be fine. He’ll take it all in his stride, just like he has done all along.

Subscribe to our new podcast, Heineken Rugby Weekly on The42, here: