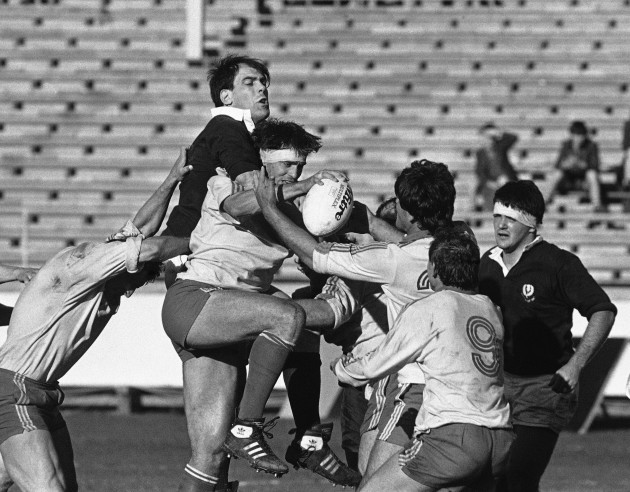

DECEMBER 9, 1989: Cristian Raducanu, who at 16 had become Romania’s youngest-ever international, has just won his 11th cap. Now 22, Raducanu starts in the second row as Romania fall to a 32-0 defeat to Scotland in Edinburgh. His teammates don’t yet know it, but Raducanu will never play for Romania again.

Following the post-match banquet, Raducanu slips away from the team hotel and watching Securitate to a nearby pub, owned by recently retired Scotland prop Norrie Rowan. Rowan, who had faced Raducanu at the 1987 World Cup, shows his Romanian friend the hidden tunnel near the back. When Raducanu makes it out on to the Edinburgh streets, he finds a policeman and asks for political asylum. A new life begins.

“I felt overwhelmed… Scared,” Raducanu recalls. “But it was very quick. Then the press were over trying to find information. It was a strange feeling. But I felt excited.”

The country Raducanu left behind was a dark, dangerous place under the communist rule of Nicolae Ceaușescu, who had been in power for more than 20 years.

“I was fortunate enough to have a privileged background in Romania,” Raducanu says. “My Dad was a highly-ranked colonel in the army, and my Mom was the Romanian Royal Mail Syndicate President.

“But look, communism or socialism is great in the books, but it’s never great in actual day-to-day living because whoever is in power, they’ve got ultimate power. They’re in charge of everything, so most of the time it becomes their own little playground. They were implementing rules and regulations and actually starving people for their own benefits.

“In the late 80s, Ceaușescu woke up one day and decided to pay all the Romanian national debt within a few years. And he actually achieved that, but the way he did it was by completely exporting everything that was being produced in Romania: food, petrol, cars, everything. Nobody had fuel to drive around, nobody had enough quality food within the shops.

“Also, everybody had to be employed. If you didn’t go to university you couldn’t be an 18 year old and be unemployed. If you were wandering the streets at night, a police patrol would stop you, ‘What the hell are you doing? Do you work? Show us your work papers?’

“And with the salaries, yes, you could afford a couple of holidays a year, you could afford to live, but it was basic living. You had two hours of television a day, mainly communist propaganda. You are not allowed to have opinions. You are not allowed to share your opinions, and if you shocked your friends or neighbors, you would probably end up in trouble and get arrested and interrogated.

It was what it was. Very, very basic, very simple. No Western programmes, no Western life.”

Rugby shielded talented young athletes from some of those issues. A promising basketball player, at the age of 14 Raducanu’s height saw him hand-picked for rugby trials. He quickly fell in love with a sport which received significant funding from Ceaușescu, who saw rugby as a way to present Romania as a powerful and a successful nation to the wider word.

A gifted Romanian international team was supported by the country’s two most prominent teams, CSA Steaua Bucuresti, founded by the army, and Dinamo Bucuresti, who represented the police force. Essentially, the players were semi-professionals in the days when rugby was still an amateur sport.

After Raducanu was scouted, he quickly rose to prominence as he grew into his 6’6″ frame.

“What happened was a scout came to our sports camp, and he said you’re actually bigger than the guy we’re looking for!

They give me rugby boots, socks, you name it. I was so proud. I loved it. And then at 16, I became the youngest-ever player to play for Romania. Two years before I had never seen a rugby ball!

“And the systems were very, very well organised, right throughout the team sports. In college, we were Romanian champions from age 14-18, so every year we had a programme where we were coming to England and playing various posh and private schools.

“During the communist era, the government took pride on sports to represent how well the communist countries were doing. Hence Romania, Russia and East Germany were doing well in the 70s and 80s, dominating Olympic Games, you name it. But they were all pretty much state sponsored.

“I finished college at 18 and was employed as a sergeant major by the Dinamo club. I was earning, let’s say a doctor’s salary at that time, as an 18-year-old, but I was playing rugby.”

Raducanu was coming through during a golden decade for Romanian rugby. In 1980, Romania drew with Ireland at Lansdowne Road during a trip which saw them beat Munster, Ulster and Connacht. Later that year, a statement 15-0 win against France led to the Home Nations awarding Test caps for games against Romania. They beat Wales in 1983 and Scotland’s grand-slam champions in 1984, while in 1981 two disallowed tries saw the All Blacks avoid a shock defeat.

At the 1987 World Cup, Raducanu was the youngest forward at the tournament, starting at number eight in all three of Romania’s pool games against Zimbabwe, France and Scotland.

Yet Romania became an increasingly unstable country towards the late 80s.

“I didn’t have any bad experiences really because from the age of 14, I was in rugby programmes and even at that age, you’d be in training camps for three months – hotels up the mountains in winter, out at the seaside in summer,” Raducanu continues.

“If you played sport, you were privileged in a sense. Nice gear, equipment, meals and everything else. Hence the performances in those days, we didn’t do anything else apart from training.

“But it became harder and harder as they started cutting off people’s foods and basic ways of living. Everybody had cars but you had no bloody fuel because it was going abroad to pay the national debts. You were waiting two or three days to get five or 10 gallons, or whatever you were allocated.

“Then, all the orphanages and everything, I only found out on television when I came to England. Because I played rugby and we were from Bucharest and were privileged, you didn’t see that dark side of disabled kids being totally ignored. But I believed it, and that was the way, nobody questioned it. They wanted strong, healthy people, and if you were disabled or weak, you were pushed away to show the strengths of the bloody communists.”

Raducanu had discussed the idea of defecting with his wife, but his actions in December 1989 had not been pre-planned, leading to fear and confusion in the days following his decision to stay in Scotland.

There was a radio station in Romania called Radio Free Europe which was broadcasting from Germany. They were illegal, but they always told the truth so everybody was listening. I was all over that station.

“Then Nadia Comaneci (Olympic gymnast), she ran off two weeks before. I remember the Edinburgh Evening News having my picture and her picture on the front page – but I thought who was I compared to what she achieved?

“But it was a strange feeling. My daughter was two months old. My wife was getting phone calls and got interviewed by the police about if she knew my plans. My Dad got retired straight away – straight away! It just shows you (the control the government had).”

One week after Raducanu’s defection, the revolution began. Later that month, Ceaușescu was arrested and on Christmas Day, he was tried in court for charges including genocide and illegal gathering of wealth. Later that evening Ceaușescu and his wife, Elena, were shot dead. Just 24 hours beforehand, Raducanu’s former teammate and captain, Florica Murariu, had been shot and killed at a checkpoint. Raducanu wouldn’t return to Romania for over six years, having been advised against it to protect his safety.

“If the revolution didn’t come so quickly there could have been issues. In the past, they had sent people to bring defectors back.

“But when the revolution came, by January they wanted my Dad to be re-employed! And fortunately, my wife joined me six months later with my youngest daughter, and the rest is history really.”

Thirty-four years on from his life-changing decision to leave Romania, Cristian Raducanu is full of energy on the end of a lengthy, colourful phonecall with The 42, detailing his remarkable life story while being kept busy by his young grandson.

The UK has been home ever since that fateful night in Edinburgh. Raducanu made a new life in the furniture business while he also continued to enjoy a successful rugby career, playing for Leeds, Sale, Bradford & Bingley and Sedgley Park, with Stuart Lancaster and Guy and Simon Easterby all teammates along the way.

He continued to follow Romanian rugby but has been dismayed by their decline as the funding fell away and the Union became “politically run.” Having once been touted as a potential addition to the Five Nations, Romania now sit 19th in the World Rankings, just above Spain, Namibia and Chile, ahead of today’s World Cup meeting with Ireland.

“They started cutting off the sports sponsorships, and that was that really as the other nations were embracing the professional era by finding more money and paying players, better facilities, the medical side of things, that’s why Romania declined tremendously from where we were into where it is now.

“I went to Bucharest to watch Romania play Italy in a friendly (last year),” Raducanu adds.

“Italy, most of their players were 21, 22, 23, some fringe players in the team. Romania had a guy making his debut at 36. How is that right? The game has changed, it’s all about fitness and strength now but they don’t seem to embrace that. When the likes of Spain and Portugal beat you… I mean, we don’t even talk about Georgia anymore because they’re on a completely different level.

“It’s hard to see (how that changes). Against Ireland, I think anything under 100 points will be a bonus. As an ex-international, to see your team concede maybe 80 or 90 points is not nice.

“But I like Ireland. You play the most invigorating sort of rugby, it show you it can be done, but you’ll definitely need a bit of luck in the quarter-finals and semi-finals and what not.”

Our conversation ends with an apology. Raducanu hadn’t been available to talk earlier in the week as he was back in Romania for a friend’s wedding in Transylvania.

“It’s fantastic now. Beautiful country, beautiful people.”

The 42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!