IT TAKES CONSIDERABLE resilience to do what David Flynn does.

A marathon runner who began life primarily as a steeplechaser, at 29, he has already experienced plenty of sporting highs and lows.

As a junior, the Blanchardstown native impressed at the World and European Cross Country events. He was also a keen GAA player growing up.

“I’ve had a group of friends since we were 13 or 14 — we’re still very good friends now. We were all excelling in whatever we did as a sport,” he tells The42. “Around six or seven of friends were playing for Dublin in Gaelic football or hurling. We were a very competitive group. I was playing hurling with them, but I wasn’t on a county team. Every day we’d have a hurl or football in our hand.

“I was getting pretty good at running. I came third at the All-Ireland Schools — John Coghlan won that day. I came second to John in the World Cross Country trials in Sligo racecourse. I had a hurling game two weeks after. People were starting to realise that running was going to be my thing, but I was trying to juggle them all, because I enjoy hurling immensely. We were in a match against St Mark’s in Tallaght. One guy broke his hurl over my leg. The whole team was very protective of me, so they all ran over to him. The guy got a red card and started crying — the whole team were about to beat the shit out of him.

After that, my coach said: ‘I don’t think you should be playing this anymore.’ I think it was the fright he got because of the potential I had as a runner, so that was the last GAA game I played.”

As far back as 2010, Flynn was an alternate on the Irish team that were European U23 cross-country champions in Albufeira, Portugal, whose members included Brendan O’Neill, David Rooney, Ciarán Ó Lionáird and John Coghlan.

Flynn, who did not travel to the event, recalls his disappointment at missing out, which was starkly highlighted by an awkward encounter: “I was coming back from America and it just so happened that they were coming back from the cross-country at the exact same time with all their gold medals on their neck.”

While some of those athletes in question went on to produce more impressive feats, as Flynn notes, most have now retired — an issue that highlights how difficult it can be to sustain a lengthy career in top-level athletics.

Flynn himself is enjoying a second life as a marathon runner, after injury problems cut short those steeplechase ambitions.

“The thing with me and the steeple, I didn’t have someone helping me perform when I was younger, so I kind of did damage to my hip,” he says. “Although I was in shape to run close to the Olympic standard, when I got to around 2k, my hip would just seize up and it would be kind of the end of it, so I had to come to the realisation that it couldn’t be fixed, even if I had someone helping me with the form.”

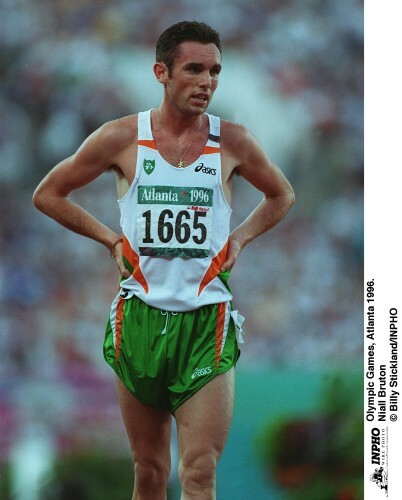

Flynn’s impressive cross-country achievements as a youngster led to him going across to train and study in the University of Arkansas, following in the footsteps of other Irish athletes who attended the college, including Alistair Cragg, Niall Bruton and Frank O’Mara.

“They were all [previously running with Dublin-based athletics club] Clonliffe Harriers. It’s kind of tradition. When you’re good, they put in a good word for you. When they say, there’s a good talent coming up, [the people in the US] take it to heart.”

Flynn received a scholarship and was originally meant to train in Arkansas under John McDonnell, the highly acclaimed athletics coach. The Mayo native’s retirement put paid to that plan, but fortunately, it worked out for the Dubliner regardless. Eventually, he linked up with another coach, Andrew Kastor, whose wife Deena earned a bronze medal in marathon running in the 2004 Olympics in Athens, and who has trained athletes of the calibre of Ryan Hall — the current holder of the US record in the half marathon

It was under Kastor’s guidance that Flynn decided to change from the steeplechase to marathon running. It was a gradual switch. In January 2016, he ran his first half-marathon in Arizona and his first full marathon in Dublin came last October.

I ran the Marrakesh half-marathon in January with a time of 64.32 [finishing 11th overall], which will qualify me for the Europeans next year and the world half-marathon,” he adds. “It’s the fastest half marathon out of all the [Irish] marathoners except for Stephen Scullion and Paul Pollock.”

In addition, on 7 April, Flynn will be running in the Rotterdam Marathon, where he is hoping to achieve Olympic qualification.

“I’m very confident,” he says. “My coach knows what shape I’m in. It’s not like I’m with a coach who’s like: ‘Well, you’re training well, but I can’t really tell you what you’re going to run. He told me what time I was going to run and I ran it. We do specific work that can tell you where you are so we know what to go through in.

“And I’ve been practising drinks for three years. Running with the drinks. What drinks go with my stomach. It’s just as important as running a marathon. Running comfortably with your drinks. Knowing when to take it, or what powdered drink to take to suit your stomach.

“This has been a plan since I started getting coached by him, Tokyo was always going to be the main goal.”

Competing in Flynn’s chosen discipline can often be painstaking both on and off the course. Funding remains an issue, as is his relatively low profile in Ireland at present.

“My mam runs a big business in Dublin, so she comes from a totally different background. Her role revolves more around money. The last thing you’re getting [in athletics] is money. So there were a lot of times where I’ve had a bad race or got injured, and she says: ‘Would you not just go get a full-time or part-time job?’ With the training I’m doing, I can’t. I’m just pushing away and pushing away, and the results are starting to come now.

A lot of people who believed I could do it are not Irish people. My coach is American. I base myself out in Morocco at 6,000 feet altitude most of the year. The guys that I train with are Moroccan. All these guys believe in me, but not many Irish people understand I’ve been full-time since I got with my coach, scraping by on as much sponsorship as I can get and it’s all going towards trips. It’d be great to make the Olympics and make everyone in this country aware of the hard work I’ve put in to get there.

“I pursue a lot of people. I have a few sponsors. But I’m chasing them and it’s really explaining to them [what I do]. I ask them: ‘What can I do for you?’

“I’ve only started working with [a new agent Derry McVeigh] now, so hopefully with a good marathon, he can help me and we can start to get the word out. This isn’t some kind of part-time thing — I’ve put my whole life into it.”

Having originally trained in Monte Gordo, Portugal — a common location for Irish athletes — it was fellow runner and friend, Belgium’s Soufiane Bouchikhi, who recommended Morocco to Flynn, after the Irishman had suffered an injury setback.

The Dubliner initially travelled over a year and a half ago, and has grown more accustomed to these unfamiliar surroundings ever since.

“It’s a Ryanair flight, you get a taxi up, very convenient and cheap enough flights,” he explains. “Moroccan people don’t speak English. It’s a small enough town [where I'm staying] and they’d be very religious. It’s a different world.

“Rob Heffernan spent most of his career going to this place and some famous runners too. [Legendary Moroccan middle-distance runner] Hicham El Guerrouj did most of his training in this place, Ifrane in Morocco.

“It was an eye opener. The heating would go off in the middle of the night. You’re place is run by gas and it’s quite expensive. The landlord’s always looking for money and I didn’t know the difference with this money at all. I didn’t know what one or 100 Dirham was. But I started to learn about the culture and started to get to know people there.

The athletes don’t really accept Europeans — I guess they think we’re lazy and stuff. But I went there and worked very hard. Now everybody knows and respects me over there, but when I first came, they’d barely even shake your hand. I just embraced it. I went over as an Irish athlete, but I wanted to learn everything about their culture, what they did and what they ate.

“You only eat with your right hand there. The other one — they call it a dead hand, so you’re kind of holding it down when you’re eating food.

“Their hands are so used to grabbing hot food, whereas my hand wouldn’t be. I’d be getting burnt all the time, so half the food would be gone before I even started grabbing it.

“I love Morocco now. I’ve a good few friends there. It’s a beautiful place, there are trails and hills and loops and really nice tracks. The most important thing is you go there to train, eat and sleep — there are zero distractions. I don’t think I’ve seen one person drink a beer in my entire time there ever.”

Spending most of his time away from Ireland, however, is not always easy for Flynn, with homesickness, among other issues, inevitable.

“My mam has cancer at the moment, so it was hard for me to leave this time. It was the second New Years and Christmas I’ve had in Morocco, so I’ve spent the last year there with my friend. This time I had another friend there, but they don’t celebrate Christmas and New Years. On Christmas Day, we meet up, and there’s no ‘merry Christmas’ or anything. You just go for your run. It’s a normal day and then you get back and send your family a few messages and you ring them, but there’s no Christmas tree.”

David Flynn smashes the @sseairtricity #DublinHalfMarathon course today to claim the 2018 title in an incredible time of 1:06:20 (TBC) #ICANIWILL 🏃🏼♂️🏆 pic.twitter.com/1ND301O7O1

— KBC Dublin Marathon (@dublinmarathon) September 22, 2018

All these sacrifices will be worth it, however, if Flynn can achieve his longstanding dream of competing in the Olympics — though that feat in itself will not be enough, as far as he is concerned.

“My way of relaxing is still training,” he says. “The way I do it is I act the job. That is my breakaway from running. I’m really obsessed with everything. Sometimes I’ll run three times a day — most days I’ll train twice and then I’m in the gym. I fill the whole day with either recovering or training or strengthening, so I don’t get injured.

I haven’t been injured in I can’t tell you how long, except for a twisted pelvis, which was a freak accident. But I’ve [almost] never been injured, because I just stay on top of everything.

“I don’t think people understand what full-time is. People say ‘he’s full-time,’ but the way I see full-time is that your life totally revolves around what you’re doing. I don’t think someone’s full-time if they have a kid. I would go as far as to say if you’re married, I don’t think you’re full-time. That’s how serious I take it.

“When I wake up in the morning and I go to sleep, there’s only one thing in my mind — that’s going to show in the results soon.”

He adds: “I think people in Ireland don’t understand. It’s not just making the Olympics. Once I make the Olympics, my coach will ring me and say: that’s done. There’ll be no party or anything like that. It’ll tick a box, but then you move on to the next thing. He’s American, he [normally] only coaches American athletes. I’m the only foreign one he coaches. He took a chance on me. He obviously saw something. He wouldn’t be putting the time and effort in if he didn’t think I could perform.

“When I run a fast time, I’ll have a meeting with him. I’ll probably go over for a training camp and then we’ll decide if we should move over full-time until the Olympics, over to prepare in California.”

Subscribe to our new podcast, The42 Rugby Weekly, here: