“FUCK YESTERDAY.

“I can’t stand old guys reminiscing about yesterday, and how great it fucking was.

“I can’t stand that shit.”

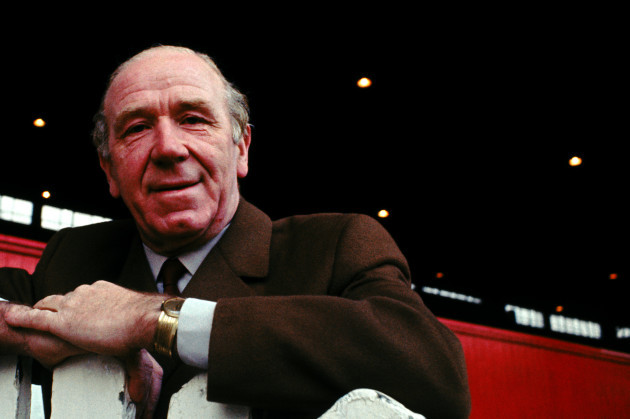

By that stage, The42 had already spent the morning muddying Eamon Dunphy’s front room with an excavation of one of the most famous careers in modern Irish public life.

******

The42 arrived around ninety minutes earlier.

Dunphy is sitting at a desk behind a laptop with phone in hand, contemplating Ireland’s prospects under Mick McCarthy with the other person down the line. He gestures The42 toward the couch, and apologises for the delay.

The television in front of him – pulled closer into focus – is showing (a happily muted) Leader’s Questions. The day’s papers are strewn about Dunphy’s feet, with a wall of shelves behind him heaving with hundreds of books.

Behind the television showing politics and toward the bottom of a small stack of DVDs is a boxset of the BBC’s classic political satire The Thick of It. Beside this stack is a small pile of books pulled separate from the shelving. Two of Dunphy’s books – his memoirs and his biography of Matt Busby – are among them.

Once off the phone he apologises again, stressing how busy he is.

Dunphy’s latest guise is the man behind a successful media start-up: his podcast The Stand attracts a six-figure listenership every week and has Tesco Finest on board as a sponsor.

There are at least five new episodes a week: football discussions with John Giles, Liam Brady, and Didi Hamann go alongside analyses of front-page issues.

The scattered newspapers testify to his doing all of the podcast’s research himself, and he rifles through his considerable contacts book to arrange guests. He then presents the show and sits in on the edit.

While the workload is heavy, you might not be surprised to hear that Dunphy is enjoying being his own boss.

“I am fascinated, and I want to work. It is better to work for yourself in journalism these days, because you have control over the product.”

Control…and space.

“Journalism is not in its golden age in Ireland. The podcast allows you to be independent, it allows you to get away from soundbites, it is long-form journalism.

“You take a topic and you can do 30 minutes on it. Take Mick Clifford, who was across the Maurice McCabe stuff for ten years; a great investigative reporter.

“Instead of having him on for eight minutes, you have him on for 38 minutes. So the listener gets it, rather than a soundbite version of it which is never accurate and always distorts it.”

The podcast is the closest thing he has had to The Last Word on Today FM, the radio show he namechecks along with his biography of Matt Busby as his best work.

In spite of a hectic schedule, Dunphy is generous in making time for The42.

Particularly as we’ve come armed with a series of ‘Remember Whens’.

******

Two years ago, I decided not to renew my contract with RTÉ Sport. At the time, they prevailed upon me to stay and, in fact, offered me a rise, a small one, to do so. However, before the World Cup I told them this time, I would be leaving.

-Eamon Dunphy, July 2018

Seven months on, does he miss RTÉ?

“No. Not at all.”

Did he watch their coverage of Liverpool against Bayern Munich on Tuesday night?

“I watched the match itself on BT. But I watched the panel, such as it is now, on RTÉ.”

Does he have an opinion on it?

“Well, they’re fine, Liam was working. But they’ve changed it. It’s, kind of…we’ll have to see if people like it.”

How have they changed it?

“Well if you don’t have Liam and Didi and John and Bill and myself, you’ve changed it. They have no time at all after the match, they have to be off-air, and they have no highlights of other games or any of that.

“It’s a new…paradigm I think they call it, and there are loads of ads. Jesus, look at half-time.”

Why didn’t he want to have any part of this new paradigm?

“It was dumbing down. And they have been dumbing down for years, in a big way.”

How was it being dumbed down? The42 noted the introduction of an interactive tactics screen in the middle of the studio in recent years.

“It was second-hand and didn’t always work. It was a terrifying experience for most of the panel to go and stand behind this thing that only worked some of the time.

“They could have got Souness back, but they didn’t. They passed. They could have got Neil Lennon, but they didn’t.

“I was there 40 years and I used to be friendly with the Head of Sport. There used to be mutual respect: you’d suggest something, they would suggest something, and then something would be agreed.

“But when it came to Souness I tried and when it came to Lennon I tried, but they didn’t…I didn’t have a voice anymore.

“Slowly it just….yeah.”

Did he feel disrespected at feeling he didn’t have a voice anymore?

“I wasn’t disrespected. I was ignored. I told them if you go there you’ll get what you need, and if you don’t you won’t. So they didn’t go there…and I went home”.

He breaks into laughter.

Is The42’s inkling that he didn’t enjoy punditry as much after John Giles finished up after Euro 2016 a fair one?

“No, no. We obviously missed John as he is the best, but Liam and Didi, fine. Really top class players and top class analysts. No-one better, nowhere better.

“That’s what you want.

“Souness, I wish we got back, as he was very, very good. That’s what you want to work on: programmes that are as good as they can be, rather than chucking any old body in there. And that was evident if you were to go forensically through the last few major championships.

“There were all sorts.

“Kenny Cunningham [he puts his head in hands]…for fuck’s sake.”

When John Giles was surprisingly uninvolved with the RTÉ panel for the Euro 2016 qualifier between Ireland and Scotland, RTÉs then Head of Sport Ryle Nugent said that he was preparing the public for a life beyond the panel, believing the “audience, subconsciously, doesn’t like change… all the research would show it’s [best to have] gradual rather than absolute change.”

Did Eamon agree?

“I totally agreed with that project. But there were people they could have got that they didn’t.

Lee Carsley is a former Irish international and he is doing brilliant coaching work with the FA. We could have got him. We didn’t even fucking ring him.”

Has RTÉ been left behind?

“Yes.”

By the football coverage on Virgin Media?

“Souness is outstanding, Neil Lennon is very good and Brian Kerr is good. The rest of them are no good.”

What about Niall Quinn?

“No. For fuck sake.”

******

Where was the outrage when the impact of Aviva debt forced the FAI to make staff redundant? The outrage when regional development officers were told their jobs no longer existed, or would face pay cuts they are still trying to restore?

What about Delaney’s salary? The governance of the League of Ireland? The curious stewarding of sections in the Aviva Stadium that are critical of the FAI? The survival of the same faces in the boardroom, with age and term limits, pushed out to prolong their stay?

The old Dunphy would have been all over that. But when a strong voice was required, he was pitifully weak.

A man that used to generate serious debate on the direction of Irish football had become an obstacle to it.

- Daniel McDonnell, Irish Independent, July 2018

Amid the profusion of tributes, the ‘Best Moment’ listicles and the Rod Liddle memes upon Dunphy’s RTÉ departure, an Irish Independent article headlined “Eamon Dunphy had become an obstacle for serious debate on Irish football and he will not be missed” stood out.

Dunphy hadn’t read it – or at least hadn’t read the above excerpt.

Is it fair?

I think he is quite right to point out that these things happened and there was nothing as a TV analyst you could do about it. We weren’t working journalists, we weren’t reporters. When I was working for the Sunday Independent back in the day, I would have addressed those things.”

Why was there nothing he could do as a TV analyst about it?

“Post an international game it would be off-subject.”

Would it really have been off-subject?

“If I had been the editor we would have done it. But I wasn’t. That’s the problem.”

So is it fair to say that RTÉ prevented him from talking about these bigger issues regarding the FAI?

“No, that wouldn’t be fair to RTÉ. These are issues that need to be done ideally by a newspaper, or in a special programme focusing on the FAI. So you need to commission that programme for TV.

“But in a post-match analysis situation, it wouldn’t be much good talking about the politicking of the FAI, if you follow me.”

Nope, not really.

“We were employed to do analysis of an international match. You could argue that these things might have fed into the performance of the international team, which I don’t think is right.

“I have no problem with being criticised by a young gun for not raising those things. My defence would be that first of all, when I was working as the Sunday Independent, I did a lot of stuff critical of the FAI and I was critical of a lot of other stuff.

“But I wasn’t doing that. I wasn’t a reporter, if you follow me.

“I would say it is fair to say I didn’t do those things, because I didn’t, and it is fair to say that the old Dunphy would have addressed those things. That’s fair.

Where it breaks down is that I was a barrier to them being said on RTÉ. I don’t get that. I didn’t have the power to edit the programme. I couldn’t go into RTÉ on a Monday and say, ‘Right, there’s a match on Wednesday and we are going to deal with all of these things.

“Someone else was doing that in there.

“There is a power thing there. For example, he could say that Dunphy didn’t address these things on his podcast. But I couldn’t on RTÉ because I had no power.”

“I couldn’t even get Souness back!

“Since leaving the Sunday Indo, and doing The Last Word, I’ve primarily been a broadcaster. Most of the time, apart from The Last Word and before the podcast, I was a broadcaster working on someone else’s programme.

“They called the editorial line. It wasn’t that I willfully ignored that, it’s that I felt the torch may have been passed to the other guys. The younger guys.”

Is the assertion that there is an ‘Old Dunphy’, and by logic a ‘New Dunphy’, fair?

“Yeah, that’s fair. I don’t mind that.”

Is the difference that one held the pen, while the other was on TV and no longer throwing it?

“Yes.

“What you can do with the pen, first of all, you can research that and you can go the press conferences and challenge and ask questions, and then you can say ‘this isn’t happening’ and you can write that piece week after week.

“You have to persist.

“I had been out of the persisting game for 20 years.”

Does he miss being the firebrand with the “crazy pen”, to quote a phrase he used in his memoirs?

“The fiery guy hasn’t gone: the platforms have altered. You could get on the podcast and talk fire and fury for 40 minutes but the listeners will be gone. You are facilitating people to tell their stories, it is a different thing.

“Everyone who is looked at closely enough over the space of 40 years, you will spot inconsistencies. That’s something that is thrown at me and it is fair enough.

“People are entitled to their point of view.

And inconsistencies aren’t necessarily a bad thing, generally speaking?

“Consistencies are the hobgoblin of the mediocre mind.”

******

Notoriety itself didn’t really bother me. But I felt remorse for the collateral damage inflicted on my family. On the night of the Homecoming, with the country in carnival mode, my seventeen-year-old son Tim was roughed up at a disco. He was a lovely, popular boy.

Now Tim was the son of ‘that bastard’ Dunphy. My daughter Colette had been getting serious grief at school and round the neighbourhood. I had become an embarrassment to my family. I was running away to France while they dealt with the consequences of having a dad who seemed to many of their friends and neighbours to be an attention-seeking freak.

- Eamon Dunphy, The Rocky Road, 2013

“It was fucking desperate”, remembers Dunphy of the reaction to his criticism of Jack Charlton during Italia ‘90. While he was corralled by fans in Italy and subjected to chants of ‘If you hate fucking Dunphy clap your hands’ the flak was dished out with profligacy, and some of it hit his children.

How does he reflect on it now?

“When you see your own children suffering…a good question would be if I’d do it again.”

Would he do it again?

“I was so fucking insensitive and so wrapped up in this journalism that I put my own kids at risk. That’s a wake-up call. When I realised that, I thought ‘Jesus…I shouldn’t be doing that’. No job is worth that.

“But I was so…engaged by the work I was doing and that may be the nature of doing it properly, or to the level I did it.

“You kind of…lose the plot. If it’s more important for you to get your story in the paper and say what you want to say, and then have your kids bullied on the street, then there’s something wrong with you.

“That’s on me.”

*****

The ideal Ireland that we would have, the Ireland that we dreamed of, would be the home of a people who valued material wealth only as a basis for right living, of a people who, satisfied with frugal comfort, devoted their leisure to the things of the spirit – a land whose countryside would be bright with cosy homesteads, whose fields and villages would be joyous with the sounds of industry, with the romping of sturdy children, the contest of athletic youths and the laughter of happy maidens, whose firesides would be forums for the wisdom of serene old age.

- Eamon de Valera, ‘The Ireland That We Dreamed Of’, March 1943

A country that trains nurses and can’t keep them. A country that has, tonight, in emergency accommodation, children who have to get up at six o’clock tomorrow morning, get a bus for an hour, go to school, walk the streets, come back to the bed and breakfast. The trolleys: 590,000 on a hospital waiting list. What on earth did we fight for our freedom for? To live in a kip like this?

- Eamon Dunphy, The Tonight Show, September 2017

Eamon Dunphy is named after de Valera, owing to his mother’s political affiliations.

The comparisons end there: The42 doubt that De Valera’s utopian “sounds of industry” had room for the trappings of showbiz, baby.

If he were alive today, what would Dev think of Dunphy?

“I don’t think he would have thought of an Eamon Dunphy, who was a football commentator and a fairly mediocre Millwall footballer! I’m sure he would have disapproved. All of those disapprove. All of the suits.”

Whereas the suits knew only corridors, Dunphy knew the streets.

He grew up in a working-class family in Drumcondra, and when he was nine, he and his family came close to losing their home. In December 1954, the banks of the Tolka burst and flooded the lower half of Dunphy’s one-up-one-down home.

Living upstairs, the Dunphys weren’t affected, but when the lower half was destroyed the landlord tried to move them out.

Dunphy’s mother fought into the Four Courts and won a battle that resonates with him 65 years on.

Given all that has changed in his life, does Dunphy still identify as working class?

Yes. Very much so. I have an empathy and an experience that is working class and I identify with those people, whether it is through sports commentary or social affairs politics. I understand what it is to be poor, to be homeless, to worry about where the next meal is or whether you’ll have a job next week.

“All of these things are pressing concerns for a majority of people in Ireland. And if you don’t understand these things, and don’t have an empathy for people, you aren’t likely to be very good at your job, be it in politics or journalism.”

******

He’s a terrible player. He can’t run, he can’t pass, he can’t tackle, he doesn’t see anything. He drives two Ferraris; I think he’s a very lucky lad to have 50 caps for Ireland.

- Eamon Dunphy, September 2013

I’m a footballer but I’m a normal person away from the pitch. But like I said, certain stuff did get a little bit personal. I think my background was brought up and there was a thing written about a car I was driving, which was mentioned.

And I definitely didn’t drive that car.

- Glenn Whelan, November 2018

Where was Dunphy’s empathy for Glenn Whelan, the quintessential “good pro” to whom he dedicated Only A Game?

“I accept the point you’re making and you’d have to be arrogant or hard to say, ‘Fuck Glenn Whelan and his family, I don’t care’.

“I do care, of course I care. I would go so far as saying that maybe I went on about it too much, but every game I saw I thought, ‘What’s he doing?’

That’s hard to square when you talk about empathy. He is a working class boy, he has done really well, someone I’m sure I’d like, but if you are working for the fans, which I was, for the people who love the game, I think you have to be honest with them.

“‘This is what I think about this guy.’

“‘The team isn’t functioning and this is the reason why.’

“And that can be hard.

“If you said to me, would you have liked to have earned the caps that Glenn Whelan earned, have had the number of Premier League appearances he had and the opportunities that go with that, would you take it and let him sit there and slag you?

“I’d take it.”

Is it a money thing? Is he jealous of how well-paid the “good pro” is today?

“No. I want them to get more. No! I wish they were getting more! I fucking love seeing players on private jets. No! After all the things we see: Gordon Banks had to sell his memorabilia; Nobby Stiles is sick and penniless.

“No! Not at all.”

******

‘Remember when’ is the lowest form of conversation.

- Tony Soprano

Dunphy says he hasn’t seen The Sopranos but agrees with the sentiment.

However, he does recount a couple of meetings from the past.

He recalls having dinner with Don King in Las Vegas – “He was a really bad man. It was amazing” – and meeting Stanley Matthews – “ a very dignified, intelligent, cultured man. And he was from Stoke, which is the arsehole of England.”

He remembers meeting Muhammad Ali at an Amnesty International event with U2, whom he describes as “the most extraordinary man in every respect.”

“A great hero. If you ever tried to measure yourself against him you quickly realise, ‘I’m a long way from here’.

“That is the thing you have to remember. There have been great, great people who have left great legacies. And gifted. Ali was the first person in the public eye in the US to take against the Vietnam War, and refuse the draft.

“He got suspended and threatened with prison. He was the first prominent American to publicly reject the Vietnam War. These are heroes.”

We now live in an age, says Dunphy, in which “the clothes of a lot of the great campaigners for social justice have been stolen by a whole army of chancers.”

“If you’re talking about Ali, Martin Luther King, Bobby Kennedy, all of a sudden you then realise, ‘Fuck me, Donald Trump is sitting where JFK sat’.

“Fuck. Me.

“That is a mind-fucking-blower. That’s where we have come to.”

In a recent interview with Dion Fanning of JOE, Dunphy revealed that his feted biography of Matt Busby – “the best thing I did by a million miles” – is out of print.

Talk turns to the idea of his own legacy. If the work of which he is most proud of proves transient and ephemeral, does he give much thought of what he will leave behind?

“Only in terms of my family. I am very much not impressed by the idea that what I do is important. What doctors and nurses do is important; what mothers do is important, what a father does is important.

“I really don’t think that being a football analyst or a journalist contributes very much, except that you might add slightly to the…gaiety of the nation.

“I don’t have any notions about myself and my place in the world, which is why I have an outrageous sense of humour and I can take the piss out of myself. I think if you think about that sort of thing, you’re off the wall.

“Be normal, be human, and enjoy the day you are there.

“And although it gets me into trouble – say what you think, don’t be ducking and diving.”

Dunphy is too busy to indulge any more of The42’s sepia.

Along with the podcast, he is continuing to work on the second volume of his memoirs, and is remaining loyal to the title Wrong About Everything.

“You have to keep perspective. The most important thing in life is to keep perspective.

“‘Who am I, and where am I in the greater scheme of things?’

“The answer is I’m a small guy in a small town, working away.

“That’s it.”

******

There may be an old Dunphy, a new Dunphy, and a newer Dunphy still… but there is always a Dunphy.

Hence the governing principle of staying alive for more than 73-and-a-half years, baby.

Fuck yesterday.