BORN IN 1990, Hannah Tyrrell missed the magic and hype of the Republic of Ireland’s Italia ’90 odyssey to the World Cup quarter-finals, but some of her earliest memories are from Jackie’s Army’s assault on USA ’94, and like many of her generation she was raised on and inspired by this legacy.

As a result, she spent much of her childhood chasing a soccer ball close to her home in Clondalkin. Growing up as the only girl on her football team, she dreamt of emulating Manchester United stars such as David Beckham, Paul Scholes, Ryan Giggs and, of course, our very own Roy Keane.

Most kids realise at some point that they will never grace Old Trafford’s Theatre of Dreams; for Tyrrell this moment came at the age of 12 when she had to leave her soccer team, regardless of talent or ability, as boys and girls were segregated.

Of course she was initially disappointed: “It was very hard as I had always played with the boys’ team. It was hard not to play anymore with your friends who you had grown up with.

“Obviously, playing with your best friends is great, but of course there is a reason for it as boys get stronger and faster than the girls.”

Unfortunately for young Tyrrell, there wasn’t a Bend It Like Beckham style all-girls team in her corner of Dublin at that time; thus began her journey as something of a code-hopper. She continued to kick round balls, but now they were Gaelic footballs with her local club, Round Towers.

Soon after this conversion she was included in Dublin’s under-14s panel, beginning over a decade’s involvement at inter-country level, through under-16s and minors to seniors, winning a number of All-Ireland titles with the Dubs along the way.

One compelling aspect of the 24-year-old’s story is that just over two years ago, as her current Ireland colleagues such as Niamh Briggs and Nora Stapleton were on the cusp of winning Ireland’s historic Six Nations Women’s grand slam, she was yet to pick up a rugby ball. She describes rugby as being ‘all the rage’ at that time; former Ireland international Sharon ‘Chopper’ Lynch encouraged her to try it at Old Belvedere.

Lynch could see Tyrrell’s potential for sevens rugby: the IRFU were on the hunt for fresh talent in Ireland’s bid to qualify for the 2016 Rio Olympics. For Tyrrell, one could say, the rest is history.

In May 2014 she had to stop playing for the Dubs mid-league season when rugby gave her the opportunity to become a full-time athlete: she was asked to join the IRFU’s centralised sevens programme, which, unlike women’s fifteens, has a structure where the women train as professionals. She quickly established herself as a force to be reckoned with in the short form of the game, and leapt at an opportunity for sevens players to also become involved in fifteens, impressing the coaches in a trial. She would make her debut on the right wing in Ireland’s Six Nations opener against Italy in Florence.

It may be heading towards hyperbole to describe Tyrrell as Irish women’s sport’s equivalent of Australian code-hopping superstar du jour Israel Folau, who segued from rugby league to Aussie rules to rugby union, where he has dazzled for the Wallabies since making his debut against the British and Irish Lions in 2013. A comparison that may make the down-to-earth Tyrrell blush, but her story so far certainly casts her as something of a sporting Superwoman.

Yet her athletic CV only scratches the surface of what a remarkable character she is.

During the Six Nations, I interviewed Tyrrell over the phone for a magazine feature. She discussed her varied sporting career, her ambition and drive, and how she was balancing studying history and geography in UCD with being a professional athlete. She even gave me a bit of a history lesson on the causes of the First World War, while humbly batting off praise concerning her recent form.

She came across as the sort of girl who just seemed to have life sussed. The girl with whom you would share a college tutorial group and envy her ability to make multi-tasking seem so easy: ‘Look at Hannah playing two types of rugby for Ireland and she really knows her stuff for this course, while I can barely make the deadlines for assignments and get to my 9 a.m. lectures on time!’

Appearances, however, can be deceptive.

In researching this book, I had arranged to meet Tyrrell in a café in Donnybrook. Despite still being in recovery from a dislocated shoulder picked up in the final match of the tournament against Scotland, she looked the very picture of health: tall, slim and confident. There was a glow to her skin that seems reserved for elite-level athletes.

After discussing her Gaelic football career in detail, I decided to ask her to fill me in a little on her academic and work background. She began by telling me that before she embarked on her current course of studies, she had spent two years studying psychiatric nursing in Trinity College Dublin, and, without any hesitation or any prompting on my part, began a searingly honest account of her own battles:

“I actually suffered with my own mental health problems. I struggled with an eating disorder and self-harm, all throughout my teenage years.

I had to take a step back from psychiatric nursing and look after myself, rather than others. I just wasn’t in the right frame of mind at the time. I took time away from my studies to let myself get better.

“I always wanted a career where I could help other people; I loved the nursing while I was there but I found it very difficult to balance it with all the sport I was playing.”

She then detailed how the particular eating disorder she struggled with affected her:

“It was bulimia nervosa but I also had anorexic tendencies. I went through periods when I would I have been skinny enough but then periods of binge eating and purging.

“It probably would have started at age 12 or 13 when I started secondary school, but it probably didn’t become a big problem until I was 16 or 17, my late teens basically. It took a while for me to talk about it.

I had a couple of very rough years. I was stuck in a cycle of self-harm: I didn’t want to get out of it but I couldn’t get out of it either.

Throughout this period she was playing under-age inter-county football for Dublin, and although the bulimia affected her football ‘in terms of moods and energy levels’, sport for Tyrrell was her only escape:

“It was the only thing that gave me a bit of relief from the constant battle that was going on in my head. It was nice to be able to get away from my thoughts for a couple of hours and be with friends and to enjoy something I loved.

“Because of my eating disorder and the self-harm, I didn’t want to communicate with anybody. It has a tendency to make you withdraw from people, but the sport didn’t allow me to. That social bond with the girls was something that kept me coming back to training and kept me sane at the time.

Even though I didn’t realise what a big impact they were having on keeping me going, it was fantastic to have the girls there. None of them really knew the struggles I was going through, but when it all started to come out that I was struggling with these problems, they were so supportive.

Tyrrell gives a fascinating insight into starting to look at how her illness was affecting the one thing that was keeping her going:

“At those times when I would have struggled with my performance … I often thought, ‘Imagine how good I could be if I didn’t have an eating disorder, imagine how if I really put 100% into it!’”

It seems that some of the perfectionistic tendencies that she admits ‘leave you vulnerable’ were also helping her back towards good health. It is with a wisdom beyond her years that she explains: “Sometimes people say that must have been tough growing up for you, but I don’t think I would change it because it has made me the person I am today.

“I have a different outlook on life now; I know what I have been through and what I have come through. It has made me the person I am and for that reason I wouldn’t change anything.”

It is somewhat ironic that rugby became the sport of choice for someone who has struggled with issues around food, eating, body image and weight, when one considers that both male and female players are required to bulk up, and this is certainly not lost on Tyrrell:

“At the beginning of the sevens programme, when nutrition became a huge thing, I was thinking, ‘Oh, it is very easy to slip back into the patterns of an eating disorder’, but I just have to keep focused on how I have to be healthy to keep performing to my best, to be putting in that fuel for the body.

It is all about positivity and talking about those negative thoughts. I am very open about what I have gone through and I am not afraid to tell somebody that ‘Look, I have been having these thoughts. I just have to stay positive.’

What makes the irony even more poignant is that she has been marked out as a player who is required to gain weight in muscle: “Actually, in the sevens programme, I am what is known as a ‘maximiser’, so I have been given a target weight and I have to try to reach that.

“It is quite hard because people think you can eat what you like, but you have to be putting on the right kind of weight. You can’t be eating takeaways every night! You have to be doing it the healthy way because they want you to gain muscle.

“When I first came into the programme and I was told there would be daily weigh-ins, I thought, ‘Oh, this is very daunting and how will I cope with this?’

I had my reservations and now I have embraced it as a challenge and I am now thinking, ‘Okay, I am going to put on weight because it will make me a better player, and if this is something that will make me a better rugby player, it is something I want to do.’

Tyrrell seems to find the environment of the Ireland sevens programme refreshing and supportive because, as part of their daily routine, the players openly discuss issues relating to their weight due to the part nutrition plays in their training.

With genuine enthusiasm she expounds on how, “With the issue of weight, when someone reaches their target weight, there is applause all around. People would be very open talking about their weight, their target weight or their body fat percentage, where we have targets around that as well.

“As we have to eat very healthily we sometimes get bored of eating the same foods all the time, so we have a nutrition group and we are constantly talking about what snacks taste good but are still healthy. People are open about it because it is another part of performance and improving our performance.”

Tyrrell believes that the mental toughness she has developed as a result of all she has been through now helps her on the rugby pitch:

“I actually think I thrive on the bigger games. Other people would be getting very nervous – granted I was very nervous for my first cap against Italy.

“But I think I do like the pressure sometimes. I think I do make good decisions under pressure. Maybe it did help.”

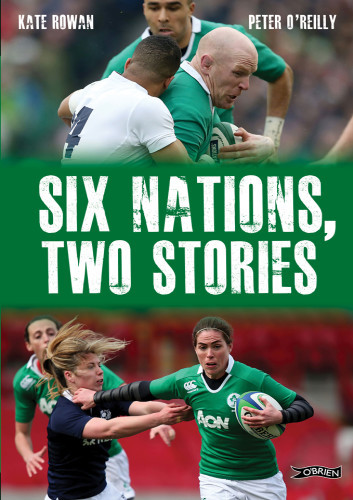

The above text is an extract from Six Nations, Two Stories by Kate Rowan and Peter O’Reilly (O’Brien Press). For more info, click here.

– First published 11.50, 25 Sept