DARK, DEPRESSING AND DESTITUTE, the country was on its knees at the start of the 1980s and Dublin felt it most keenly.

With the economic slide, a heroin epidemic and an inevitable surge in crime, an editorial carried in The Irish Post in April, 1983 described the city as “the most blighted and most dangerous of Europe’s small capitals”.

In inner-city spaces – like Dolphin’s Barn – the issues were magnified.

And yet, within a Dublin 8 community that was frequently dealing with a toxic cocktail of social ills and bad press, there existed something particularly magical. A temporary getaway. A place that provides the backbone to one of the most remarkable Irish sports stories.

“My father was in the army and a colleague of his, Ulick McEvaddy, had a share in the Dolphin’s Barn ice rink”, says Keith Daly.

Ulick and his brother, Des, were the two main drivers behind it but they had this notorious problem with people stealing customer cars from outside the rink. At the time, it was the height of the joyriding fiasco in Dublin and you couldn’t keep a car on the street without it being interfered with or robbed. So, Ulick asked my Dad to get a few of his buddies together and they did a bit of a stakeout. The word was basically put out – ‘Don’t touch any cars in this fucking area or there’ll be trouble’. So, my Dad got this little nixer just minding the cars every night and I’d go along with him.”

“The rink opened in 1981 so I started going around 1982/83. I was about eleven or twelve and I became your typical rink rat. I was there five or six nights a week and most of the weekend. I moved from just skating to actually working in the skate hire and picking up a few quid. That meant I was there all weekend and eventually I started to pick up a stick and a puck and I’d have a great time.”

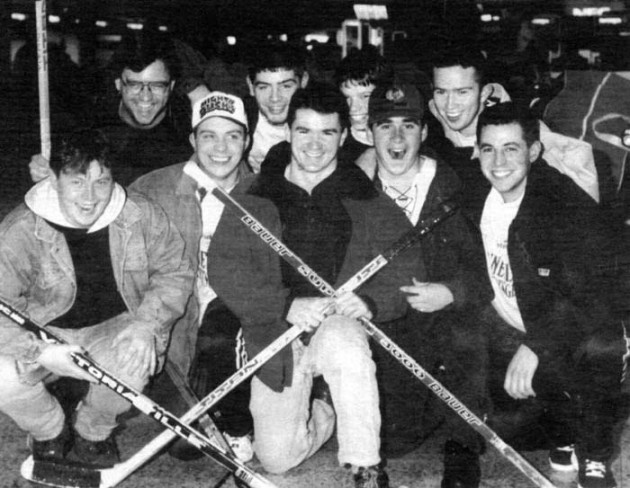

There was a group of locals who were cut from the same cloth. Like Daly, they’d already accumulated hours and hours of ice time and were ready for a new challenge: hockey. It was a small but passionate motley crew. They managed to procure sticks and pucks from somewhere, though other equipment proved more elusive. Not that they cared. They were ignorant and fearless. And what about learning the rules, regulations and intricacies of a game completely alien to even the most die-hard of Irish sports fans? Well, that’s another story.

At the Royal College of Surgeons on St Stephen’s Green, word had quickly filtered out amongst American and Canadian medical students that a rink was up and running and only a thirty minute walk away. They turned up, laced up and quickly became the shiny new objects in Dolphin’s Barn. Eventually, the locals and the outsiders conversed and bonded and a weekly Sunday night hockey ritual soon began. Soon, there was even enough interest to set up an underage team called the Dublin Dolphins. So, by 1983, the band of brothers felt strong enough to organise their very first game.

“In those early days, the management brought in some ice-hockey teams from the UK – like the Liverpool Leopards or the Streatham Red Skins – and they’d come over, go on the piss and play a game in Dublin, basically”, Daly says.

“For some matches, I’d even operate the scoreboard. There’d be a couple of hundred people watching and baying for blood. The Dublin team would’ve been made up mostly of imports and maybe some slightly older Irish lads who’d been skating a bit longer than us. Most of the Americans and Canadians weren’t interested in doing coaching or anything like that because they just wanted to turn up and play. In fairness, we didn’t have the right equipment or the right skates or the right coaching so it was hard to mix in with fellas who’d been playing all of their lives. But still, Irish guys who are keen on hockey tend to pick everything up pretty fast. I don’t know if that’s the hurling thing or not.”

And it marked us out as different. For young people, especially in south Dublin, it was an ideal place to go. Dolphin’s Barn was on the bus route into town. And you’d go for a couple of hours – boys and girls. It was a lot to do with the opposite sex, really. If you were a good skater, doing something unusual on the ice was even better in that regard.”

By the middle of the decade, there was some wider traction. The Ice Bowl, an Olympic-sized rink, opened in Belfast and attentions quickly turned to the possibility of arranging games and cultivating a rivalry. Given the political climate, everyone got a little more than they bargained for.

“Bass Lager sponsored a team in Belfast called the Red Wings and they had some fancy gear and a few Canadian imports and all of that”, Daly says.

“It was the embryo of the [current UK Elite Ice Hockey League team] Belfast Giants, in many ways. There was a double-header organised where we put a team together to play them in Belfast and again in Dublin, which was a lot of fun.”

“In those days, you had the British Army checkpoint at the border so the vehicle would stop, the soldier would get on, walk through the bus holding the weapon – all of that. It happened all the time. I remember in the late eighties, The Troubles were at a particularly difficult point and the RUC would actually meet us on the outskirts of Belfast and drive us in. On one occasion, they actually stayed with our bus as we went inside to play the game. So that was pretty intimidating.”

There was another time when we went up to play a team called the Orange Rockets and even on the ice you’d get stuff like, ‘You’re nothing but a Fenian prick’. Or, ‘You’re a Catholic bastard’. So it was a scary place to bring a team. I was seventeen or eighteen and you’re facing grown men who don’t care about the game. They were just trying to hurt you. For a while it was really intense. But it settled down once the federation was organised in the late nineties and there was a lot more cooperation. People became aware that if they wanted to attract kids to play the game, you couldn’t have that kind of treatment and it got a lot better. I was coaching teams when I was eighteen – probably even driving the bus heading up there – and you couldn’t be bringing thirteen or fourteen year-olds into that environment”.

Still, despite the glitz of the Belfast trips, it was a slog trying to find the resources necessary to improve things. It was always a struggle to access even the most basic of equipment.

“We had one goalie stick”, Daly says.

“It broke at some stage so one of the guys repaired it by putting metal plates into it, which basically held the bottom of it together. We had one set of goalie pads and the straw would fall out of the bloody things when you’d be skating across the ice. You just couldn’t get your hands on equipment. It was so hard to come by and very expensive. I was looking at a picture earlier and there’s fellas just in skates and jerseys. Some of them aren’t even wearing helmets. You didn’t have access to it so you didn’t get it.”

We just didn’t have the coaching. At one stage, myself and Cliff Saunders would have been a bit more experienced and took on the mantle of ‘coaches’ but outside of picking up a book in a library, we didn’t have any knowledge. We’d look at diagrams and pictures in books. Like, try and explain the offside rule to a twelve-year-old from Tallaght or Crumlin without any video to show them where they’re going wrong…But we were learning all the time. It kept us off the streets and my entire teenage years were taken up by skating and arranging trips here, there and everywhere.”

“I took a team to Glasgow in 1987 or 1988 and there was about twenty in the group for an Under-16 tournament. And we arrived at the rink, got all our gear on and hopped on the ice. And the referee comes over and says, ‘Where’s your face masks?’ And I told him, ‘Erm, we don’t have any face masks’. And he says, ‘You can’t play the game. You have to wear face masks’. And we were all saying, ‘What? Is this for real?’ So we had to borrow the other team’s equipment to play the game. But all the guys had never worn face masks before so it was a comedy of errors. But it was all self-organised. There was no federation at that time. It was a club. A group of guys who just wanted to play the sport. You didn’t care for the regulations. We learned by doing, basically.”

By that stage, it wasn’t just North American imports involved in the Dublin setup. Somehow, other memorable characters heard about the ice-hockey team percolating in a tiny rink in a gritty, grimy corner of the south inner-city and wanted a piece of it.

“One of my favourite guys was a German fella called Rudi Freiburg and he’d started an import business in Dublin”, Daly remembers.

“He was solid as a rock. A big guy, with the cliched ’80s moustache, an excellent player and way above anything we’d experienced. He was tough as nails and somebody that really stood out. Another guy was Greg Fitzgerald, a Canadian, who just had great, silky hands and it was so hard to get the puck off him. Off the ice, he was larger than life and was always great craic to be around. We also had a Russian guy, Dimitri, and what a fucking player he was. He was unbelievable. He could do things with a puck I’ve seen very few people make happen. He was a bit of a piss-head and there was a bit of unpredictability about him. But if you got in a fight, he was the guy you’d want having your back because he could handle himself. There wasn’t too many Russians around Dublin at that time, especially not in Dolphin’s Barn. And he looked like one too, sometimes he’d even have the big hat on. He was doing some electrician work, I think, but it could’ve been anything. And there was a US marine who was working at the Embassy on his two-year tour and heard there was a rink. He just said, ‘Yeah, gimme some of that’. And he’d come down and was your typical marine. You’d wind him up, let him go and he’d fucking crush anything. He had so much energy. He wasn’t the best player ever but made up for it in determination and enthusiasm. Just a crazy guy.”

Another development in the mid-1980s was the addition of a second Dublin rink in Phibsboro, on the northside of the city. And it was here that Pete Lalor, an American kid from Massachusetts, showed up one evening.

“I played hockey at Amherst College and then played a year in Holland in a place called Dordrecht”, Lalor says.

“But I’d also applied to med-school and was accepted to the Royal College of Surgeons. So after the twelve months in Holland, it was a six-year stint in Dublin. And it was word of mouth that connected me with the guys. Somebody found out I played hockey and said, ‘Hey, you know there’s a rink over in Phibsboro’ and that was it. But I’m not sure I’d even call it a rink, to be honest. It was a dark and dingy building and didn’t look like a rink at all. It was a converted movie theatre. It was fairly barren, not very clean and the ice surface was maybe about a third of a proper rink. The ice was poor quality, almost like pond ice. And they had a tractor-style Zamboni (an ice resurfacing machine) and a rolled-up rug and they’d drag it along. It catered to public skating, really – something just for kids to do. There were some really thick boards around the surface but they weren’t complete and didn’t have doors. So there were two openings where you just got in and got off. So it wasn’t even an enclosed ice surface. But I was just glad to be skating. Hockey is one of those sports that you just obsess over. I loved the people involved. And the Irish guys were the same.”

Did it raise eyebrows? Absolutely. It was hard to legitimise it to people, especially because the rink was so poor. If we had a full-size rink and a resourced team, maybe that would’ve been different. But there’s such an unfamiliarity with the sport in Ireland. I remember talking to my family about it but I don’t think they understood the simplicity of what I was doing. I don’t think they realised how crazy it was to play pick-up hockey on a tiny piece of ice in the middle of Dublin.”

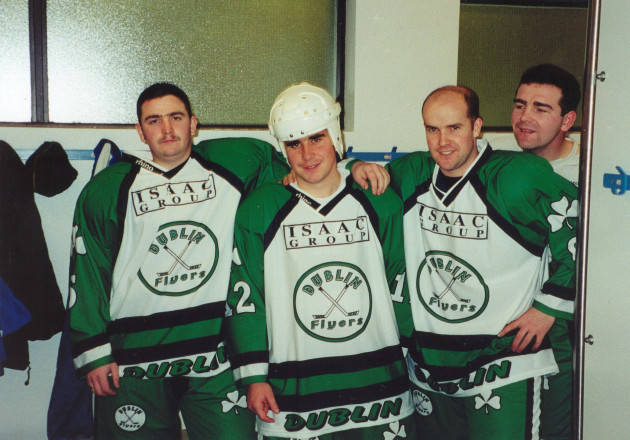

By the time Lalor arrived on the scene in the mid-1990s, there had already been regular games between the Phibsboro and Dolphin’s Barn groups. It was a tight family of likeminded lads who all adored this physical, draining, thrilling battle. And, much to Lalor’s surprise, the standard had come a long way in a short space of time.

“The skill level of some of these Irish guys was pretty good”, he says.

They could compete and make it fun. It wasn’t like I was showing up as a college player and was bored out of my mind because I was killing everyone. The standard was surprisingly fun and effective and worth it. And I’d emphasise that by that stage more than half of the guys were always Irish. I have nothing but fond memories and I was received so well. Everyone got on really well and we put together a team, the Dublin Flyers – essentially a men’s recreation side – and went to Scotland to play in tournaments and we’d do really well. We’d win it most of the time against these Scottish teams. I can not remember a time when we weren’t competitive. It was not often that we lost. Some of the Irish players – somehow – had developed their skills to a decent level. They were just athletes and they loved the game. At every opportunity they would skate and knock the puck around. The trips to Scotland were just great weekend piss-ups. Like, drinking and hockey go together like peanut butter and jelly.”

During a six-year spell in Dublin, Lalor became involved in coaching some underage hockey sides and witnessed an inexplicable surge in youngsters getting involved. With available rinks, they could hone their skating. And everything else followed.

“Eventually – thanks to Cliff Saunders and Mark Bowes – connections started to be made within the International Ice Hockey Federation, we started to attend various conferences and then we ended up submitting a national junior team in 1999″, Lalor says.

“We did some off-ice training and were at the Phibsboro rink at least twice a week and the kids put their heart and souls into it. They see the gear and the goalie stuff and they say, ‘Woah, I want that’. They want the uniform, the armour – to be that hockey warrior almost. But hockey is expensive and it’s a commitment and you can’t just step on the ice and play right away. But those kids had been skating at the place for a few years and were just messing around before we organised them a little. But there was a buzz. And everyone loves the Irish, so anyone that heard about us at the international federation level was extremely supportive and Mark and Cliff made some very influential friends within international hockey. It’s the best things in life – beer, hockey and Ireland – it’s like a magic mix.”

For a while, everything was on the rise. After becoming a member of the world governing body in 1997, a senior Irish men’s team played at their very first internationally-recognised competition in Iceland seven years later. And even when the Phibsboro and Dolphin’s Barn rinks shut their doors for the final time, the Dundalk Ice Dome opened in 2006. But it was gone by 2010, as was a short-lived hockey league.

And though there’s been regular murmurings that it will reopen imminently, the country is still without an ice skating facility. As a result, hockey has fallen by the wayside.

“I was the vice-president of the federation for a while”, Daly says.

“But when the Ice Dome closed, I took a step back. I still love the sport and the family has been to New York, Tampa, Toronto, Boston last year. Every time we go somewhere we’ll catch an NHL game and the kids love it. If there was a full-size rink here tomorrow I’d immediately sign up for the Over-50s team. It’s a fantastic sport and very unfortunate we don’t have the resources to see the full potential of the game here. Undoubtedly, if we had a rink or two, it would be a massive sport in Ireland.”

Daly and Lalor know better than most. For quite a while, they were part of something special, something that will stay with them forever. The common bond was hockey. Nothing else mattered. And that never changed.

“One of the guys was an electrician”, Lalor says.

Another was a manager in a department store. Another guy ran a bar. One of them was a carpenter. One of them was in the army. But across the street from the Phibsboro rink was a pub and we’d grab a few pints after our sessions on Sunday nights. It was one of those things. Coming to Dublin, I found something in common with a bunch of guys who liked to play hockey and loved the game and enjoyed a beer and were funny as shit. And it was kind of like a dream come true for me because, as a Lalor and given my family background, I really wanted that Irish identity. And I never had to force it. I would say that most of the North American guys involved with the hockey programme had Irish roots. So most of us fit right in regarding the ‘Irish pride’ element. We were well aware of the history. And we just wanted to support our team-mates, our brothers, basically. To this day, if those guys called me at any point, I’d do anything for them.”

Daly echoes the sentiment.

“Hockey was the unique identifier between a group of guys”, he says.

“It didn’t matter where you were from. You just got the skates on, grabbed your stick and off you went. It was hockey first and everything else came second. We’d socialise a lot. One of the things the sport has given me is lifelong friendships. Some of the people I still know today, I met them playing hockey. It’s a unique sport in Ireland and it is like a family. I was looking at something recently and there were guys like Robbie Byrne, Mark Bowes, Cliff Saunders, Kevin Kelly, Willie Fay – all guys I could meet for a pint tomorrow.”

It was tough on Lalor returning to the States after six years. After all, he’d found a second family. But he’s grateful for the moments and the memories.

“Ireland is very different from North America”, he says.

“It’s a different way of life and I really took to that when I was there. The social aspect, particularly. So many fond memories. If I walked into a pub in Dublin right now with all of those guys there, we’d just pick up right where we left off. It would be so much fun, to be honest.

So much fun.”

Photographs courtesy of Pete Lalor.

Special thanks to William Fay for his assistance with this article.

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!