IN THE DAYS after Joe McDonagh’s funeral, his family received countless letters from all over the globe. Commiserations and recollections. All were gratefully received yet one, in particular, stood out.

The pillars of Joe’s life were GAA, the Irish language and education. Two of the boxes were ticked during his time with the Vocational Education Committee. He worked in various regions across Connacht, but his time with the Galway County Board was cherished because it allowed him to engage with the Gaeltacht.

“We got this one letter from the janitor in Rosmuc community school,” recalls Eoin McDonagh, Joe’s son.

“A wonderful letter talking about Dad. Every time he came to visit the school, he made a point of going down and finding him. Asking how he was fixed and if needed any strimmers, equipment, stock. Are you being looked after? ‘He treated me like he did the principal.’

“He said he always appreciated that.”

- For more great storytelling and analysis from our award-winning journalists, join the club at The42 Membership today. Click here to find out more >

It is five years since former GAA president Joe McDonagh died. Today, the competition named in his honour gets under way. It is a fitting tribute to a man who made an indelible mark on the association and wider nation. A career so broad that after all this time, his friends and family are still trying to chart it.

As a player he won an All-Ireland with his county and delivered one of the most iconic moments in the GAA’s history, singing joyously from the steps of the Hogan Stand.

His presidency paved the way for the removal of Rule 21, transformed coverage of the sport, established games development plans, formalised coaching education and endorsed GAA units abroad. McDonagh’s figure features on every tile in the national mosaic that is the modern organisation.

Noel Lane was there at the start and the end. A club and county team-mate. From day one, Joe McDonagh demonstrated the leadership necessary to eventually lead the GAA.

“I’m from the far end of the parish in Ballinderreen. I went to national school and mass in Ardrahan. All my friends were there,” Lane explains.

“When I was 10 or 11, I hurled with the national school. I suppose I was showing signs of being a reasonably good hurler.

“A farmer from Ballinderreen who had land beside us called to the house and said they were playing a game against Kinvara that evening, an U12 game. He asked me to go back. I landed back to Ballinderreen that evening having never really been.

“My brothers played with them, and I wanted to play for Ballinderreen as well.

“Anyway, I cycled over and a group of lads were already there. A 10-year-old Joe McDonagh came over to me and asked, ‘are you Noel Lane?’ I said I am. He looked at me and said ‘you are welcome to Ballinderreen, we’ve heard a lot about you. We are delighted you are playing with us.’ He brought me over to the rest of boys and introduced me. I was really shy and nervous, overawed I suppose at meeting this new crowd of young fellas.

“Joe put the hand on my shoulder and welcomed me. From that day on we had a special relationship.”

This is a trait referenced by all who knew him. McDonagh loved people. If you have five minutes to spare for Joe, he had 10 minutes for you.

Encounters and conversations proved the fuel that helped him sustain a hectic lifestyle. Work until late, four hours rest, up and out early. Chalking up thousands of miles on the country’s roads. Every highway and laneway, visiting schools, clubhouses and communities.

For Noel Lane, he was always a friend and often a mentor. The duo formed part of Galway’s breakthrough generation; a rising wave produced by the Coiste Iomna initiative of the 1960s aimed at reviving the game. Joe’s father, Matt, was actively involved in enacting that around Galway.

Lane and McDonagh both won a South Board U21 Hurling Championship in 1972 with Ballinderreen. The same year they won an U21 All-Ireland title with their county.

“There was something special about Joe, the way he would talk in dressing rooms. He could call a spade a spade when he had to.

“He challenged people, wouldn’t be afraid to be constructively critical when it was for the benefit of the team. He had certain standards when it came to discipline and preparation. Stuff around attitude and behaviour. He was someone to look up to, I always did.”

A few years separated Joe Connolly and Joe McDonagh. Today they are two county icons. Connolly entered University College Galway in 1974 and knew of the Ballinderreen clubman. That year, he captained their freshers’ team and won the first-year championship.

“Joe was very aware a good bunch of hurlers were coming through,” says Connolly with a smile.

“The holy grail was the Fitzgibbon. It finished up we won it in ‘77, I think that was Joe’s sixth Fitzgibbon campaign. He had savage ambition to win one, time was running out. He did a Masters in Celtic Studies and that time, believe me, Masters were rare enough. You needed tremendous brains altogether to do one.

“You’d nearly be in awe of that academic achievement.

“No more than a few of us, he took his time to go through college. We won the Fitzgibbon eventually and it is a competition that was seriously important to us. Even now it is a great linkup. We are still a close enough bunch as it happens.”

Joe’s uncle, Sean Mac Dhonncha, was a well-known traditional singer. While in UCG he was involved in the Patrician Musical Society and Taibhdhearc na Gaillimhe. It was during these trips that Connolly saw his vocal talent in full display.

“That carried over to the county. One thing was ability. But the other thing, UCG was phenomenal craic. Sing songs and everything. I was thinking about this last week. Joe would start to say, ‘party, party, party.’ Out to Corrib Park. Long before texting, you’d have to smell out a party.

“It came into the county set-up. Older fellas like John – my brother- were mad out for craic but never had an outlet, an easy way to do it. Then the UCG crowd came in. Joe, myself, Conor Hayes and Niall McInerney. It became the norm. When the 1980 team get together, it is the nights we remember as much as the days.

“We had 10 of the team able to belt out a song. It was flipping brilliant. Great fun. People often say, ‘would ye have won more if ye weren’t like that?’ We wouldn’t have won what we did without it.”

Galway took on Limerick in the 1980 All-Ireland final. It was the first championship encounter between the sides in 17 years but a familiar frontier for the Tribesmen. Not since 1923 had they handled the Liam MacCarthy Cup.

In the build-up to that tie, McDonagh’s made his hunger to end the famine clear.

“He was an All-Star. A lovely wing back, two sided and strong out. There might have been better hurlers, but not many had an influence on a team like him,” explains Connolly.

“He was a phenomenal orator. On the Wednesday before the final we used to eat in the mart in Athenry. Delighted to have it at the time. What started out as sorting arrangements became a few people talking.

“Next thing Joe took off on about the All-Ireland. He culminated with ‘I am not coming back on Monday beaten this time.’ He had the loss in ’75 and ’79 as captain. After he said that PJ Molloy belted the table. Literally lifted it. Cups and saucers started to fly. It was a moment that always stayed with me.”

What more can be said about what came after? Victory, a heart-filled speech, one powerful ballad, the perfect moment. Providing an antitode to the variety of losses the region suffered over the previous decades.

To truly understand what that meant for Connolly and Galway, you need to know the backdrop. Connolly’s brother, John, hails Joe McDonagh as the smartest man he has ever met. His father had similar affection for him.

“I remember one of my earliest memories of Joe. When Galway won the league in 1975, I joined the panel the following October. There was a few great days and nights. Myself and Joe were going out to Seapoint one night for a dance. My father drove the car and he loved Joe McDonagh. All my life he spoke Irish, a Leitir Móir man through and through. He had a huge affinity for Joe.

“On the way out in the car Joe started a sean-nós song. The kind of thing that goes on forever. By the time we got to Salthill, he was only halfway through. The two of them got out of the car, stood on the street and Joe kept singing the song until he had finished it. The crowd walking around on a balmy summer’s evening. Life will never get better as it is now sort of stuff.”

With that, Connolly begins to strike up the note. The sound of simultaneous melancholy and joy, reminiscing on an idyllic warm weather evening with friend and family by his side, singing as they looked out over Galway Bay.

Noel Lane regularly comes across that 1980 clip on Facebook. Without fail, it brings a tear to his eye. What’s more, the episode was utterly natural. Connolly went back to his roots to make the speech. Cyril Farrell, a mature student in UCG, knew of McDonagh’s voice and encouraged him to take the mic.

“The great ballad of the West of Ireland by a voice like that on an occasion like that,” Connolly recalls.

“It was all spontaneous. My speech was spontaneous as well. Joe’s hopping up and singing was completely spontaneous. Nothing had been pre planned. It just culminated in a moment the occasion deserved.

“The hunger of the West of Ireland. I knew myself I’d mention the immigrants. That is the world we lived in out here. Decades and decades of population decimation.”

The force of character was paired with a clever mind. In 1987, his club wanted to develop their grounds. The decision was taken to combine it with a mayor selection for Ballinderreen. Four candidates, whoever raised the most money won.

The goal was a lofty £100,000. They smashed it. Joe led the way, touring London and New York with his songs and tapes; charming Gaels and shaking the bucket.

A lifelong love affair that never left him. Even after he was elected Uachataran, McDonagh continued to hurl with his club. In 1996, he was captain and full-back of their Junior B outfit. Lane led the forward line while Joe’s son, Eoin, brought the legs around the middle.

“We were in our mid-40s,” says Lane. “Joe got as much enjoyment out of that year and the craic we had. Junior B being Junior B, a couple of pints were never lost along the way. We were both finishing up. Ah, it was marvellous.

“There is a lovely photo of himself, Eoin and his father with the cup. He loved playing, loved the green of Ballinderreen. To win a county medal with his club was a dream.”

Administration was a natural progression. He was a founder of the Galway City Post-Primary Schools Hurling Committee and member for a decade. He chaired development boards, working groups and youth committees. It was a climb so spectacular that it was no surprise when he contested the 1993 presidency, still in his mid-30s. Jack Boothman won out. Nevertheless, everyone knew Joe’s day would come.

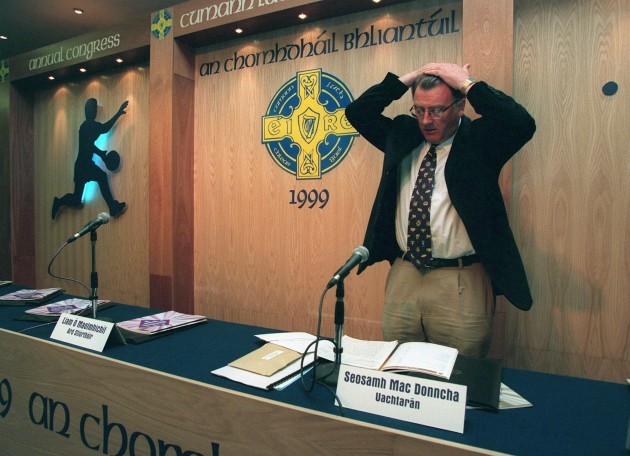

Sure enough, in 1997 he assumed the mantle. In doing so he was charged with modernising the GAA as it lumbered into the new millennium. This was not to be a smooth transition.

Watching the Galway native in action was to have a profound effect on Sean Kelly, who would go to become president from 2003 to 2006. It provided valuable lessons that would be required when it came to rule 42.

“Joe was intelligent, but he was also independent. I saw that when I was chairman of Munster council and he was president.

“In many respects, subconsciously I learned you cannot take everything that comes from headquarters as gospel. Joe challenged that. Particularly in terms of specifics that were never published and shouldn’t be. Pensions and so forth. He brought a transparency that ensured support from grassroots.”

Studying at Aberystwyth, Wales and working in the bars of New York in the early 1970s forged a deep appreciation for clubs abroad and their vital role. It was always about more than the games and how they were played. The security of a social network all over the globe was cause for celebration and needed consolidation.

That is why he linked up with the Paris Gaels and guided the formation of the European County board. “He wanted to bring the GAA abroad into the fold. To give them equal recognition and support. He did more than any before him,” says Kelly.

A foreign endearment stoked by experience, ingrained by blood. Joe Connolly is keen to stress that McDonagh was a Galway man, out and out. That meant something.

“There is also the west of Ireland thing. This great like with immigrants. I think that was in the DNA of Joe McDonagh. More than presidents from elsewhere. If you are from where we are, immigration has been part of our lives always. For Carna where his family came from. Ballinderreen and Galway where he did his hurling. It is no wonder he had such an affinity for abroad. It was a centre point of his presidency.”

Conscious of the past while enthusiastic for the future. Under McDonagh, the amount of live TV games multiplied. The value of overseas rights quadrupled. He also insisted that both the ladies’ football and camogie finals be screened live on separate Sundays. It was a line in the sand, the contract would not be signed otherwise.

In 2000, he declared it his “dearest and fondest ambitions” that the three governing bodies come under one umbrella.

His recall and ability to recognise a face was legendary. He carried a sincere interest in people and their stories into every encounter. It is a contributing factor in McDonagh’s rare ability to be liked and respected.

When the time came, challenges were met headfirst. In the face of controversy, the schoolteacher was always guided by his convictions and ability to determine right from wrong. That was sorely tested in 1999.

Prior to the first test in the international rules, it emerged Graham Geraghty said a racist remark towards Damian Cupido during a practise match in Melbourne.

There was no doubting it was rooted in immaturity and a prompt apology was offered after the game. Yet, despite management’s insistence that the matter was settled, Joe knew better.

While he had a long-lasting bugbear with the noncompliance of the GAA rulebook, there was a bigger picture for the association. This was not about the international rules or one exchange between two players. It was about the role the GAA wanted to play in an Ireland preparing to move into a new century. If the organisation wanted to play a part in a fast-evolving homogenous society, it had to show it.

McDonagh intervened and Geraghty was suspended for the first test.

Encouraged by the Good Friday Agreement, a desire manifested to abolish the rule which prohibits British army and police forces from becoming members of the GAA. Once again, resistance reared.

When they played together, Connolly never would have guessed McDonagh would go to become president. Be that as it may, when it came to pass he saw a familiar steely resolve.

“The climb from being a player to president of the GAA, feckin hell. Committees after committees. People going on and acting the shite. How you would put up with that, I do not know. I couldn’t do it for five minutes. I didn’t think Joe had the patience for that.

“The power of his personality. Now they call it networking, with Joe it was just friendliness. He was a young fresh voice in a conservative GAA but they started to respect him. He had a stubbornness in him. You would have known that. He was no shrinking violet. Ever.”

In the face of personal abuse and sinister phone calls, McDonagh did not back down. This was a vital chance to inject some momentum into the peace process. He attempted to abolish the rule at the 1998 congress. It wasn’t successful though it did set the process in motion. A special congress was arranged, and his desire was subsequently enacted during Seán McCague’s reign.

The criticism that came over battles with the GPA was minor in comparison. McDonagh’s preference was for the Players’ Advisory Group and saw the players association as an unauthorised body. At the core of the debate, both sides had the same motivation: player welfare. The disagreement orientated around the best way to climb the tree.

Sean Kelly saw these battles and challenges unfold all around him. It left a lasting impact.

“I sat at a table and saw Joe challenge things. He was straight up, did not hold back. That was new to me. It was wonderful. It got me thinking this isn’t as straightforward as we were led to believe. It isn’t about yes men. You need to put your cards on the table and facts and figures.

“Another part of his contribution is that he did so much for coaching with Pat Daly. Pat is an independent mind as well. He mightn’t have always been appreciated as he deserved at HQ but without the support of the president, he wouldn’t be able to drive the modern coaching methods we now thankfully have.”

Pat Daly first encountered Joe on the field when he hurled with Waterford. He is now the GAA’s director of games development and research. From 1991 to 1994, Joe was chair of the coaching and games development committee. Himself and Daly formed a powerful duo.

“He never saw the games as an end in themselves,” says Daly.

“They were a means to an end. Human growth and social development. That was the bigger vision. Some people don’t get that. They get preoccupied with skills, drills and winning. That is important in its own right but the organisation is about cultivating better humans. That is why we exist.”

Daly routinely references three things: mission, vision, ambition. Usually, people’s eyes glaze over in response. But for him these are core issues. Why do we exist? How do we achieve it? What do we measure? Once those fundamentals were met, the task was equipping coaches to enact it.

“When we started out on this expectation with Joe in the 1990s, coach education was effectively skills and drills. We put a number of coaching manuals together that were reflective of the national organisation that was well able to stand on its own two feet. That put the person at the centre of the process. The child, the youth and the adult.”

It put the GAA down a noble path. They set up the Go games in 2004. At first, they were under 8, 10 and 12. Now it’s 7, 9, 11. The principle is pure. Every gets to play, no substitutions.

Daly remembers the contribution a Belgian expert made at one of their coaching conferences in recent years. The speaker pointed towards the elder statesman sat at the top bench and said “that is what benches are for. Old people to sit on. Not kids to look in at games.”

Not enough people realise that now, never mind in the 1990s. The Waterford native met resistance when he presented on the need for humanistic and holistic measures. Yet no matter where he went, Joe backed him.

“He could see the merit in it, he could see the vision and passion for it. It was wonderful to work for him. People like Joe and Peter Quinn, I put that down as the highlight of my time in Croke Park working with people like them. Quinn was a financial genius. Joe was the human genius.”

That mentality led to the wonders of the modern underage network. In 2006 they introduced the Cúl Camps. Local communities engrossing children in the games during the height of summer. A million kids have gone through since and they generate more revenue than the All-Ireland final.

Daly was a big campaigner for the Joe McDonagh Cup to be called what it is. For Joe’s family, it is a source of pride, especially because of the competition itself.

“We were delighted as a family,” says his son, Eoin.

“Anything that has been done to recognise him, you’d be humbled and honoured that people would do it. Particularly when it is things that are closely aligned to his passions.

“I mean he was a GAA man and played Gaelic football, U21 with Galway and the Sigerson campaigns. He played with Cortoon in the Galway championship, but hurling was his first love. He was also desperate to grow it. For his name to be linked to that second-tier competition, that has become a great platform for competitive hurling for those teams.”

Kelly hails it as one of the great GAA traditions. Joe was just 62 when he passed away after a short illness. It was only right that his contribution be honoured.

“That is probably the greatest honour posthumously. A national cup, Joe was a national figure. When we introduced those second and third tier competitions, just look who they are named after. The greatest hurling names in the GAA. Christy Ring, Nicky Rackard, Lory Meagher and Joe McDonagh. That will live forever more.

“It helps keeps his legacy and memory alive. Joe was not just a great hurler; he was also one of the best administrators the GAA every had.”

Joe Connolly still finds it hard to rationalise his absence. The sadness creeps up on him in softer times.

“I know life goes on and you can’t live in the past but, you look back in your idle moments something does come… 20 May 2016, Joe died. The previous September my younger brother Gerry died. He was only 27 and he got a very bad cancer diagnosis. They were the two wildest characters of my hurling career.

“Brilliant memories of battles on the field and craic off it. Being in the dressing room with them. Dressing rooms are special places. If you have the right person in a dressing room with you, you’ll never forget them. Two of ye wearing the same jersey and determined to give everything for it.

“This is not bullshit talk. There is something about the sense of place that goes with the jersey and love of team-mates.

“The ability to look across a dressing room, nod and say to yourself ‘with that lad in the team we can’t be beaten.’ That is a leader. A great team-mate and the life that went with it. You just find yourself saying, ‘fuck it. Joe isn’t gone, is he? Joe can’t be gone…’ As I would with Gerry. It is so tangible and overt. If they aren’t there, things have really… it is a manifestation of how time has moved on.

“The only thing is the fact that our high opinion of him is validated by the high opinion the GAA has of him now and the wider community. Not just as a player but as a progressive president.”

That is the solace. There are legendary memories, lives enriched and a healthier GAA. It is all thanks to Joe McDonagh.

- For more great storytelling and analysis from our award-winning journalists, join the club at The42 Membership today. Click here to find out more >