Updated at 16.58

WARNING: THE FOLLOWING article contains violent imagery.

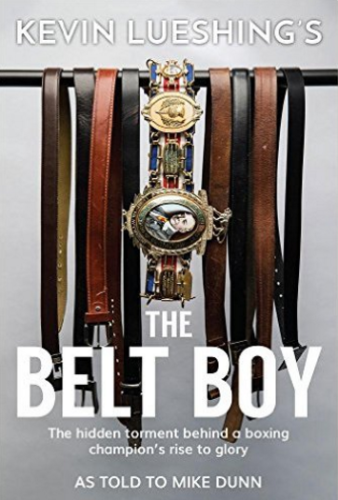

Below is an extract from The Belt Boy, which looks at the life of former World welterweight champion boxer Kevin Lueshing.

My father was a man I could never lovingly call ‘Dad’, no matter how much I wanted to.

And I really wanted to, in the natural, happy way any son should call his father. I could only call him by his Christian name, George, because — by the time I was five years old — he had already beaten emotion and love out of my tiny body and soul. I would only call him Dad if I was begging for mercy.

Beatings were a cruel, callous and regular way of life in my childhood. I genuinely can’t recall happiness, laughter, Christmas, birthdays, a harmonious family growing together in a loving environment. We were the opposite: totally dysfunctional. I had three brothers and two sisters; we grew up in wretched poverty.

Christmas presents would be necessities – socks, pants, jumpers. Where most children enjoyed laughter and love in equal measure I endured pain, hatred, fear, racism and physical abuse. In equal measures.

Beatings were the only constant but the crimes never justified the punishments. Ever. I took many but the one I have just referred to was by far the worst. In fact it became legendary among my brothers and sisters. Nothing that ever happened to me as I went on to become a champion boxer, and fight for a world title, compared to that beating.

I have to admit the beatings were never gratuitous — they were always for a reason, even if that reason was spurious. On this occasion, I had been bad at school, fighting, and the school suspended me – two days before term was due to end for the Christmas holidays.

One of my teachers said: “Don’t bother coming in for the last couple of days, Lueshing. We don’t want to see your face again until next term.” I said: “Fine.”

I thought I was being smart and had got off lightly. Until I remembered George was at home. My father worked on oil rigs and would get called all across the world to do jobs as and when they came up.

The trouble was, he hadn’t received any calls for some time, so he was spending his time at home, getting edgy, drinking too much, smoking dope. It was coming up to Christmas, he’d got six kids and he had no work.

I could see all this, I could sense the tension around him, so, instead of explaining what had happened at school, I got up the next morning, shouted “See ya!” – and went off on my own like I was going to school in the normal way.

Instead, I headed to the park, where I stayed until 4 o’clock, on my own, killing time. And it was no barrel of laughs there — thick snow had been falling, it was freezing cold, real icy cold, and all I wanted to do was get back home into some warmth. I did the same on the second day, counting down the minutes, shivering endlessly, trying to take shelter in an old bandstand but at the same time trying not to get noticed.

It really was no fun but 4 o’clock slowly approached so I set off for a nearby BP petrol station, where my brother Edwin was working. I wanted to get some sweets off him. But as soon as I walked in, he screamed: “Oh man… you’re going to get a lickin’ tonight.” I remember the fear of that moment and stammered: “Why, why, what do you mean?”

And Edwin explained that a social worker had phoned the house and told my mother about the school suspension. Edwin was the executioner and his words were my death sentence. I asked Edwin what mood my father was in and he replied: “Kevin, he’s been smoking.”

That gave me some hope. I actually thought: “Touch, I might be alright, that might calm him down a bit.”

So, I headed home. Over the years, I’ve thought long and hard about that walk home and the feeling that consumed me as I walked the half mile. It was a feeling I experienced again many years later when I walked towards a boxing ring to face world champion Felix Trinidad in Tennessee. It was stomach-churning fear, anxiety, a dread of what lay ahead – an anticipation of impending hell. I was ten years old and I was terrified of going home: I knew deep, deep down what was about to happen.

The feeling was so over-powering: raw, naked dread. But I couldn’t stop myself, I couldn’t not go home; just like I couldn’t turn round in front of thousands of fight fans and millions of TV watchers and not face Felix Trinidad.

So I went through the door and instantly the house felt like a morgue, like a graveyard. My brothers and sisters were all there, and they were looking at me like I was a lamb to the slaughter. He’s going to beat you, man. Their eyes were telling me to run but I was thinking: “Just stay calm.” I remember my mum saying: “Kevin, yer dad wants to talk to you,” and then I heard his voice. “Kevin, where were you today, boy?”

And in the next breath he was yelling: “Don’t bother lying to me, son. This is your last chance.”

So I came clean and explained I was in the park. George demanded to know why I was there and not at school.

“Because they suspended me, but I was too scared to tell you. And I’m scared now, I’m scared of you, Dad.”

And I said ‘Dad’ – not out of love or affection. Out of panic, out of fear and out for desperation. I was crying now because I knew I was done for.

“Don’t bother cry, don’t bother,” he said, “because that is only going to make it worse.”

The word ‘worse’ was said with such ferocity it felt like a blow in itself. “Get upstairs and get into your pyjamas.”

I trudged up and as I was climbing I could hear my mum pleading: “George, pleeeezze, George. Then screaming: “GEORGE, GEORGE. You can’t beat him with that, don’t beat him with that,” at the top of her voice, pleading, hysterical.

Upstairs, my brothers were begging me to jump out of the window and run to my granma’s house. So, I took Errol’s shoes, which were two sizes too big for me, jumped out of the window – in my pyjamas – and I started running, fast as I could.

I was panicking now and headed for the BP garage again, knowing Edwin would still be there. I told him what had happened, he gave me 10 pence out of the cash till for a bus fare, and urged me to go to Granny’s.

And he gave me one of those black, fluffy jackets they used to sell at petrol stations in those days: he saw how I was shivering with the cold. I jumped on a 54 bus, arrived at Granny’s house, knocked on the door and yelled: “He’s going to kill me.”

I didn’t have to tell her who, she would instinctively know. Bless her, I’m about four stone, very frail, very small, I didn’t start growing until I was about 16, and she said: “Don’t worry son, you’ll be alright here.”

The main reason I went to Granny’s was because the tactic had worked before, for my brother Andrew.

My dad was going to beat him, he ran to my granny’s, my dad calmed down and he didn’t get a beating. I sat down with her; she gave me some food and some Horlicks and I slowly started to feel calmer when suddenly there was a crashing bang at the door I shivered, colder than the cold outside and thought

“Christ, help me now, he’s here. George is here.” My gran opened the door and said: “You ain’t taking him, George, I’ll call the police.”

And I remember him saying: “Call the fuckin’ police’ and he brushed right past her. Suddenly gran yelled: “Quick, Kevin, run upstairs, run upstairs to my bedroom and jump in the wardrobe.”

I pelted upstairs, straight into her bedroom where there was one of those big old-fashioned wardrobes, like in the film The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Only I wasn’t about to be jumping into some magic land full of bloody fairies and rosy gardens. I climbed in and tried to hide behind some tatty old clothes hanging inside.

All of a sudden I saw a light come on through the crack in the door. Panic consumed me: I was mortified, real, deep terror, so suffocating I could barely breathe with it. I knew what was coming, the expectation of pain, the knowing there was nowhere left to run to. It would be him and me; he’s bigger, angrier, he has the weapons and I’m just a child.

Knowing all this, seeing what was about to happen in my mind, picturing it, picturing the hell, the pain: how could a child rationalise or escape that?

A child in a wardrobe, shivering now with gut-wrenching dread, nowhere else to go other than hell. And that moment would return to haunt me when I turned to boxing, when I walked towards the ring, knowing pain and hurt was waiting for me.

But at least I was taking that walk because I wanted to, because maybe I could stop the pain and make my opponent suffer it instead. But it was no boxing match against George; it was no level playing field. He’s coming, he’s coming.

The terror pumped through me, the door flung open and he screeched Jamaican slang at me: “Where you there, where you there?”

The clothes I was desperately trying to hide behind were now being violently yanked apart as George moved in to grab my cowering body. I was hunched up, praying that somehow he would fail to see me.

But his hands appeared through the swirling clothes, grasped my hair and dragged me out – not gently but violently and urgently.

George was tugging at me like you might tug at an old suitcase jammed inside. Silly, irrelevant details I remember so clearly. Maybe an analyst would say they’re all significant, maybe it was just the sight of George’s big status symbols that made him feel big and important in his own mind.

It’s just I remember he had his white sheepskin coat on, his cowboy boots on, his gold rings on, his Rolex watch – and I was still in my pyjamas.

He carried on dragging me down the stairs – bump, bump, bumping – and my gran was yelling: “George, George, don’t take him.”

Oh Christ, I’m scared. It was the fear that was so suffocating. I’d never known fear like that. Was it the fear a condemned man feels as he walks towards the gallows? For a child, and I was a child, it felt even worse.

George pulled me to the car, barking “You come with me,” and I was crying, I had no defiance or resilience left in me. I was like a floppy rag doll, nothing left inside, drained of everything.

I know now that I was in deep trauma but I couldn’t rationalise such things then. I was just sated by the fear. There was no need to fight, no logic to it: the lion had his prey. All that’s left is death.

I remember my gran shouting somewhere in the distance, “I’m calling the police George,” and then she’d gone and I was in the car alone with me captor. A big black shiney BMW – it was spotless. We used to clean his wheels every Sunday; we had a toothbrush each and some stuff that kept the wheels silver. George kept the car immaculate. Spotless, clean, and I was in the front seat alongside him.

The silence between us was overwhelming and was only broken when he switched on the radio. It was Bob Marley, it was bloody ‘No woman, no cry’. I remember this because I liked Bob Marley then, I still do now.

George stayed silent. There was only the music between us until he suddenly turned the volume down, leant slightly towards me – his evil eyes piercing into mine – and spoke in a menacing, poisonous whisper: “This is going to make it WORSE.”

And the word ‘worse’ echoed in my head and still echoes in it today. Worse, worse, worse. I was a child. And he banged his hand down ferociously on the arm rest, repeating the same seven words until they sounded like an hysterical chant: “This is going to make it worse. This is going to make it worse.”

He didn’t explain what was going to make it worse: I was too terrified to ask but I assumed he meant the fact he’d had to come to get me from Granma’s. Suddenly he pulled over and stopped the car. I shivered. This is it.

But I looked outside and saw we were alongside Unwins, the bloody off licence. I knew what that meant: he was going to get some liquid, some fuel. He wanted to get tanked up before he started on me. That’s what ‘getting it worse’ really meant.

He stepped out, in his fancy fuckin’ coat and boots, said nothing and walked straight into the store as calm as could be. He was in there for what felt like an eternity. As the seconds turned into minutes and the dread inside me boiled and boiled, I thought about making another run for it. It was though my whole being was saying: “Get out Kevin, get out, run, run for your life.”

It was clear thinking: I was alone, waiting for my executioner to return and there was clear daylight in front of me and the chance to run straight into it. Then, just as quickly, I thought to myself: “Kevin… what are your options?”

And I weighed it up very quickly: where would I run to? I couldn’t go back to Granma’s, he’d just come tearing back in a worse state. My mind carried on dissecting my choices: Is there anyone else? Who’d be willing to save your skin, Kev? Who, who? The police? No. They’re white, you can’t trust white men. I’m just a little Paki. So I stayed.

The light went off as quickly as it had switched on: there was going to be no escape. George got back in the car, he had his cans, and we drove home. I walked into the house and he instantly barked: “Take your clothes off and get outside into the back garden.”

I was crying now: the moment had come and stripping me naked was the first part of the torture. Taking my clothes off, exposing me so I’d be open, vulnerable, defenceless, a pathetic, weedy and insignificant body with no resistance and no strength.

I stood outside in the freezing, biting cold in a shabby pair of Y-fronts, eleven years old, shivering violently and waiting for the horror to begin while George stood in front of me, still in his coat and boots. I could hear my mum, stood by the back door, wailing and shouting “No George!” in between hysterical convulsions.

Her sobbing clearly rattled George; he turned from me and roughly pushed her back into the house – locking the door, so she couldn’t get out. And I could see my brothers with their faces pressed against the window, squinting into the darkness to see what was going on. Waiting for my screaming to begin.

Then George suddenly had something in his hands, dangling down – jump leads. But not like the ordinary jump leads you get from a petrol station: these were for juggernauts and lorries, these were big, heavy duty, coated in thick rubber with copper inside.

I remember staring at them as George started to wind one of the connector ends round his hand so he could get a solid grip. The cables were dangling by his side: one black, one red – those colours screaming out at me against the white snow.

And the open jaws of the other connector ends were swinging around his ankles, mouths open, ready to take bites out of me, laughing at me, mocking me.

I am a child and I am to be torn apart, cut to shreds, lacerated, split open. George was close now and whispered menacingly: “Hold out your left hand.”

Seized with terror, I slowly pushed my trembling open palm towards him. As soon as it was close enough for his liking, he lashed the jump leads down on my feeble flesh, already blue from the freezing air.

And before the pain and the shock even started its journey through my body, he ordered me to hold out the other hand, and he struck me again. I can still see the look in his eyes. As he hit me, my eyes locked on to his, looking for tiny clues that might tell me where the next blow would be coming from. George had already taught me that survival tactic. And he wasn’t finished: “If you move your hand, I’m going to give you more,” he snarled.

My eyes stayed locked on his as more blows rained in. One, two – the pain was unbearable and I instinctively put my hands between my legs in the hope it would give them some temporary comfort. But George wasn’t having that: “Hold your hand out again, boy, and don’t move it.”

I offered him my left and right in quick succession, hoping to spread the pain evenly, but always keeping my open palm upwards, so George would be happy that I wasn’t trying to stop him having easy targets.

But the pain was rapidly becoming unbearable: like a sharp chill blain, the sort you feel when it’s freezing cold outside, you have no gloves and you suddenly trip unexpectedly and throw out your palms to try to break the fall. A bit like that but way more severe, way deeper.

I cried with the intensity but after a while I simply rolled with the pain, becoming increasingly braced for it as every blow rained in. Even George tired from the exertion and needed an interval: so, he took some swigs of beer before coming back for more.

“Open your fuckin’ hand”– bang – “open” – bang – “again” – bang. Then back for another little break until it was time to start up again. And while he was hitting me, I became consumed with hatred.

I wanted to fight back but more than anything I wanted to say: “You’re bullying me, Dad, don’t beat me like this, talk to me. Please don’t hurt me any more – please, Dad. Dad, I love you; don’t do this to me, Dad.”

I wanted to call him Dad, only because I reasoned that word might connect with him and soften him. But I couldn’t say it, I was too scared, he was hurting me and I just wanted it over and done with.

The Belt Boy by Kevin Lueshing is published by Austin Macauley. More info here and here.

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!