JACK GREALISH IS not the only footballer who has had to make a difficult decision relating to international football and Ireland in recent times.

Lukas Browning Lagerfeldt was born in Drogheda to an Irish father and a Swedish mother. At the age of two, he moved to Sweden along with his family and has been living there ever since.

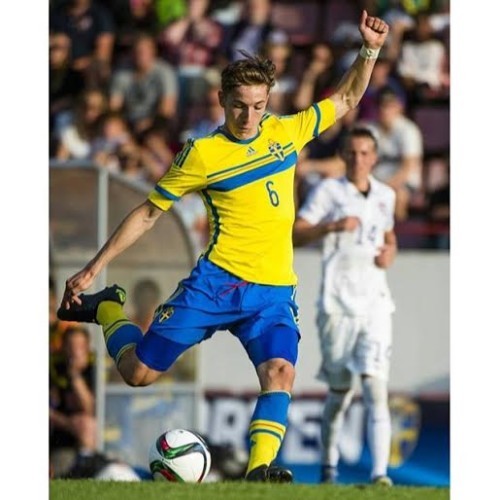

Now aged 16, Browning is considered a highly promising footballer. Having played the game avidly since the age of six, it wasn’t long before the youngster caught the eye of the Swedish underage set-up and naturally, he proceeded to play for his adopted country.

Nevertheless, shortly thereafter, Irish footballing officials became aware of the starlet’s Drogheda background, and consequently, Browning had a big decision to make: would he play for Ireland or Sweden?

“Most of my family is Irish. I wanted to make my family proud and obviously, I feel that I’m Irish,” he tells The42. “It was a tough decision but in the end, it feels like the right decision (to choose Ireland).

“The family have different opinions. It’s difficult to decide what way you want to go. You can obviously change again, but that’s not in my thoughts — I want to play for Ireland in future.”

A defensive midfielder with considerable technical ability, Browning admits he needs to work on the physical side of his game. He is currently a member of IF Brommapojkarna’s U17 team and has even played a couple of games for the U19 side.

Based in Stockholm, Brommapojkarna are not considered a top club in Sweden, though their youth academy is famous, having produced several well-known Swedish footballers, including current international John Guidetti, while they also have an affiliation with Manchester City at present, having previously had close links to Manchester United’s youth set-up.

“It’s a huge academy, one of the biggest in Sweden,” Browning explains. “But I’m doing well and I’ll hopefully get a few chances to go abroad now.”

Browning also has gained experience with renowned Dublin club St Kevin’s Boys (whose past players include Robbie Brady and Jeff Hendrick), having moved to Ireland to live with his father for six months back in 2013. This change in his footballing environment, he admits, was somewhat of a culture shock.

“It’s a lot more physical in Ireland, whereas it’s more about technique here in Sweden. We play on Astro all the time here in Sweden, and it’s obviously easier to play technical football on Astro.

“In Ireland, you play on grass, and you need to fight a bit more against the bounce of the ball. I’m used to the Swedish system, so when I went to Ireland, it was a bit difficult to adapt. I tried to pick up something from that, and I think they wanted someone physical [in Sweden] and Ireland needs some of that technique. It’s a good mix if you can combine the two of them.”

In a recent interview with The42, Bray U19s coach Maciej Tarnogrodzki suggested Irish schoolboy clubs could benefit from playing on Astro, particularly in the harsh winter months when normal pitches are often unplayable. Having gained first-hand experience of playing in such awkward circumstances in Ireland, would Browning also like to see Astro pitches become more prevalent on these shores?

“I think so,” he says. “During the winter, it’s great. Here in Sweden, we’ve loads of snow, so in the winter, we train on the Astro and it’s heated, so the snow and ice doesn’t stick — it’s nice to have that possibility.

“But you need to play on grass as well to be able to adapt to that,” he adds.

Irish youngsters’ inferior technical ability to many of their foreign counterparts was evident in Browning’s first game at U15s level for the Boys in Green. They were beaten 1-0 by Holland in February of last year and the teenager admits “we didn’t have much of the ball”.

He has since played in European Championship qualifiers against Finland and, as luck would have it, Sweden.

But while Irish starlets are still playing catch-up with countries such as the Swedes when it comes to technical ability, Browning senses the situation is changing for the better.

“I think they’re going in the right direction. Irish young players are being encouraged to play and I think (the standard) is getting better. I like the way they want us to play football and to try to develop us, instead of just trying to get results.”

Asked which footballer he considers to be his role model, Browning does not instantaneously list several current superstars. Instead, he points to a senior player at Brommapojkarna, Serge-Junior Martinsson Ngouali.

“He’s more of a role model as a person,” Browning explains. “He helps me with plenty of things. We do lots of individual training (together).

“But as a footballer, the likes of Roy Keane, Paul Scholes, these types of players are a massive influence.”

Browning dreams of one day playing senior football for “a big European club,” but he is under no illusions about the challenges he faces.

A small minority of young players ultimately sustain a professional career in the game, and Browning is well aware that the next five years will be crucial in terms of his development.

“I train a lot,” he says. “All my spare time goes into training. It’s organised training with my team, and I do individual training as well. So I train up to eight times a week and then I have a game at the weekend.

“School is difficult,” he continues. “But it needs to be done.

“People go to parties, get interested in other stuff, but I’m trying to stay focused. I know that if I get through this period and work hard, I’ll get a reward at the end of it.

“You can get caught up in that kind of stuff and your head is everywhere else but football. You need the right people around you to guide you and to have the right level of mental strength to be able to get through it.”

Often, former players and current professionals old enough to remember a different era will tell you that underage footballers have it too easy these days. There have been instances, particularly at cash-rich Premier League clubs, where youngsters are earning fortunes without even having played a single first team game. These players are treated as if they have made it and consequently, they grow lax and complacent having not even kicked a ball at senior level.

Browning agrees that many young players are overpaid, but believes there are pros and cons to the current situation.

“My opinion is that having comfort (is more important than money),” he explains.

“Getting playing time and feeling good going to training every day, and liking where you live (is important). I wouldn’t be all about the money, I’m all about the comfort.”

And while Browning may be aware of the significant challenges that lie ahead and the intensive work he must put in over these next few crucial years of his development, the youngster still allows himself to dream. Watching Ireland’s recent 1-0 triumph over world champions Germany, he couldn’t help but feel inspired.

“It made me want to play for Ireland even more in front of that crowd at the Aviva,” he recalls. “It was amazing!”