LIFE AFTER FOOTBALL is seldom straightforward.

Speaking to The42 a few years ago, the Secret Footballer noted: “Remember the stats for former footballers — one in three will get divorced, one in three will suffer a mental illness and one in three will be declared bankrupt.

“Doesn’t bode well for me, does it?”

While the top players these days earn the type of salaries that set them up for life, and which their counterparts 30 or 40 years ago could only dream of, there are different pressures for the modern footballer.

Michael Owen had a better career than most, winning the Ballon d’Or, lining out for Liverpool, Man United and Real Madrid among others, securing the Premier League title, the FA Cup and countless other accolades.

And yet, after retiring in 2013, he noticed a void that would eventually prompt him to seek help.

As a player, the Chester native never considered psychology particularly beneficial to him. During Glenn Hoddle’s tenure as England manager, the young striker reluctantly agreed to visit a team psychologist, though the ensuing conversation had no impact.

Having spent a year out of the game, in the summer of 2014, Owen started to realise that the obsessive, single-minded drive that benefited him as a player was having an impact on his family life.

“When you’ve lived as a footballer and you get all the adulation, and you get a release when you score a goal, everything comes out,” he tells The42. “Then, when you’re not anymore, you’re just a normal member of the public. You can almost feel a little bit worthless at times. I probably struggled. I knew it was happening and I suppose it came over time as well.

At the end of my career, I was semi-retired so to speak anyway. To have that mental attitude I had that was so positive in thinking you were very good at something, and then all of a sudden, that something you’re very good at doesn’t matter anymore. It’s just a memory.”

Owen is careful not to exaggerate this difficult period. There have been footballers far worse off and in darker places, he believes, though he still emerged from the predicament a changed man.

“I just needed to clarify a few things — why, how and what. Certainly, I had no demons or mental issues or anything like that. I just wanted to understand a little bit more why you feel like that, why there’s a resentment, jealousy or whatever. I’m finding out what was I feeling.

“I did that through my football channels. I only had one meeting. That was absolutely great. It pointed me in the right direction in terms of what I was thinking. It was good for me.”

It was the star’s behaviour around his family that ultimately convinced him to get counselling. Owen had been together with his wife Louise since the pair were teenagers, though at one point, their marriage appeared to be under serious threat. Urgent action was consequently required to prevent the family from splitting apart.

“I’d take everything out on Louise,” he recalls in the book. “I’d accuse her of spending all her time with her eldest and ignoring the other kids. It wasn’t even true.

“On one hand, I’d criticise her lifelong passion for dressage and then turn it against her — even though, on the other, I’d do everything humanly possible to support her in her pursuit of it. It made no sense.

“We’d continually get into arguments about petty things and I’d always resort to the same, predictable tactics whereby I turned everything back on her. I was like a broken record always repeating the same song.

“Inside I knew that I adored Louise and would never, ever want to split up. Yet, I could feel everything slipping away.”

One of Owen’s biggest strengths as a footballer was his capacity to avoid reflection or self criticism. If he missed an easy chance, for instance, he was never one to dwell on his mistake. Yet what was a strength on the field became a hindrance away from it.

“I ended up blaming my wife or eldest daughter… Well, not blaming, but having a pop at them for different things,” he recalls. “I suppose I was always like that as a player. I was always right on the edge. Before a game, my mum or wife would dare not speak to me because I was quite edgy. My mind was obviously focusing in on the game and little things would just set me off.

“I’d like to think I’m very normal. I’d like to think everybody else would be the same. When something important is about to happen, you start focusing and getting a little bit short with people. I think that’s just what I was like. But of course, you’ve got to conform to normality again at some point, and that was a little bit of a change for me.”

Owen rejects any suggestions that the counselling sessions he attended after his career ended would have helped him become a better footballer had he sought help when he was younger. On the contrary, the former player believes his single-minded, self-obsessed approach ensured he maximise his talent.

My sheer obsession with trying to be the best was the biggest help in the world. Mentally, you look around. What did I have? What did a lot of other players have? What makes you one of the best, as opposed to just a standard player? It’s pure obsession, pure mental drive.

“So I think it certainly helped me throughout my career having this one-track mind. But of course, it hinders you in other parts of your life as well. That sort of obsession — it’s almost a sort of delusional attitude.

“My mate always says when I go on the golf course, he can beat me 100 times out of 100. He’s a far better player than me. But I go on to the first tee the 101st time, and I’m not just kidding, I genuinely think I can win. It’s impossible, but that’s the mindset.

“So obviously, in the jokey way I’ve mentioned, that hinders you. Because you’re convinced of your own ability, when half the time, you’re crap at something. So it can hinder you and from a family point of view, it hindered me in the odd little way.

“But to understand yourself, which is what I needed to do, understand all my strengths… They ended up overlapping and sometimes becoming my weaknesses.”

He continues: “I didn’t even view it as counselling in a way. I just wanted to have a chat with somebody that was in that field. I just wanted to try to understand myself a little bit better and understand why I was getting this feeling every so often.”

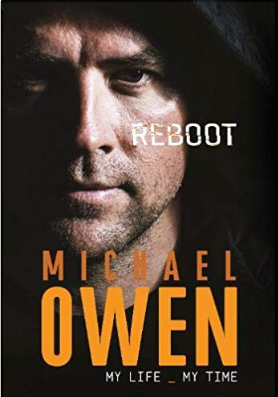

‘Reboot’ is an apt title for Owen’s book. At his best, the talented striker performed with a machine-like efficiency and irrepressible self-confidence that few opponents could handle. Yet he felt like a completely different person after attending the counselling. Having been primed for life as a footballer since the age of six, suddenly the anger and focus that had characterised his time as a top-class athlete dissipated.

“The staff at Manor House Stables used to think I was a right weirdo,” he writes. “I’d go to races, sit in the box at Chester on my own, reading the paper, not wanting to talk to anyone. That’s just how it was.

“Nowadays, I’ll talk to pretty much anyone. I’ll be the first to want to go to the pub with my mates and I’ll be the last to want to go home at the end of the night. At 3am, they’ll all be saying: ‘Let’s go home, we’re almost forty!’ But for me, it feels like I’m living life in reverse on some level.

“Because my early life was just so utterly bizarre and brilliant at the same time, I never had the opportunity to do lots of things — like going to the pub with a bunch of mates without having to worry about training the next day. Now I can. I’m making up for lost time.”

Owen admits that the image of him, from early on his career, that his agent and others cultivated for commercial purposes, was somewhat false. He was portrayed as a flawless, clean-cut, boy-next-door type, when in reality, he considers himself in a far different light.

In the first part of my career, I kept myself to myself. No one really knew me. Everyone painted me as this whiter-than-white person and whatever way they painted me, I wasn’t really that bothered about changing anyone else’s opinion. I just wanted to be the best footballer I could be.

“But of course, you grow up and times change. I suppose people now see the more real me. Whether that’s a more opinionated or outgoing person, more social, all these things. So I think that’s just come with age and experience and just being what you are.”

On the subject of football and fame, and its addictive nature, he adds: “In the summer, if we didn’t have a World Cup or European Championships, I used to go on holiday. I’d enjoy the first week, or maybe the first two weeks, but if we were off for three or four weeks, I’d be going stir crazy. The third and fourth week I’d be almost again feeling like [I was detoxing from] a drug — I hadn’t scored a goal or been sung to or been asked for my autograph. It was almost like you crave what you’re not getting, or what you’re used to.

“I’d feel exactly the same in the latter stages of a holiday for the summer, and it was the same feeling as well when I retired. It was sort of an emptiness. ‘No one’s interested anymore’ type of thing.”

Nowadays, Owen says he is in a much better place and enjoys a far healthier relationship with his family in addition to leading a more balanced, less football-obsessed lifestyle, where he will happily go to school meetings or attend hockey matches of family members — all the activities normal dads do, essentially.

The 39-year-old, who scored 40 goals in 89 appearances for England, has also learned to take social media less seriously. The in-built mental ‘shit filter,’ which he says he has always possessed, is as strong as ever.

“Of course, with social media, there’s a lot of abuse and things like that and I can filter it out,” he explains.

I suppose it gives me a worse outlook on the world and life. If I read my Twitter feed, 90% of it is abuse, so I [used to] go out into the world and meet people and think 90% of people are abusive and looking to be nasty. But the reality is totally the opposite. I’ve never ever had people just come up to me to my face and say anything like what I would read on Twitter. So it is a totally false world, and as soon as you can get used to that, then fine.

“But at the start of social media, I did just start thinking: ‘Jeez, if this is how people feel towards you, you’d be almost scared to walk the streets.’ But you quickly find out that it’s just a front by a lot of people and the majority are nice, basically.”

Reboot: My Life, My Time by Michael Owen is published by Reach Sport. More info here.

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!