ELITE TENNIS PLAYERS and swimmers have been getting bigger for years, but arguably no sport has witnessed an evolution quite like rugby.

The arrival of the professional era, combined with advances in sports science, means the sport is almost unrecognisable to the game in the mid-1990s.

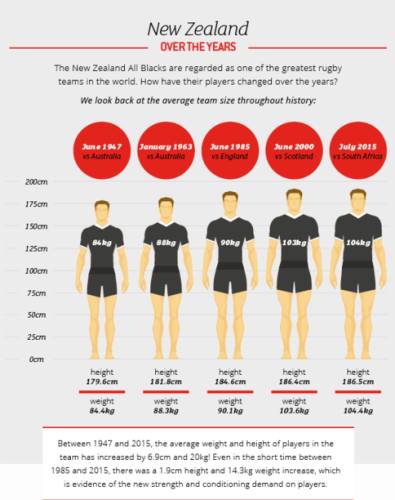

Rugby players are training smarter than ever before and as a result, they’re faster and stronger. The average All-Black in 2015 weighed 15 per cent more than his 1985 counterpart, and stood almost 2 centimetres taller.

“You have to admire the physique, the power, stamina and strength of the modern day player,” Ed Morrison, 1995 Rugby World Cup final referee, said before the 2015 World Cup.

“They work incredibly hard to achieve that – and as a result it’s a completely different sport. The level of training at the top end has turned these men into complete athletes, and they’re so much bigger than the former players.”

The modern rugby player is a different animal to the amateur athlete of the past. Irish youngsters move from schools rugby into provincial academies, where they are groomed for the elite level.

Along with an increase in size, they’re becoming more intelligent. Of course, not every prospect makes it to the top, but those that do manage to break through are finely-tuned athletes with a deep understanding of their mind and body.

The Irish provinces are doing everything in their power to ensure players maximise their talents, stay injury-free and, most importantly, produce results on the field.

Rugby coaches instill layers of sophisticated tactics that are not immediately apparent. Players must master the skills while also surviving in a contact-heavy sport that regularly features high-speed collisions.

Strength and conditioning, diet and psychology are three of the key elements that help mould the professional rugby player. Lifting weights is still a core pillar, but it’s a little more scientific these days.

“It used to be just based on strength, then it progressed to strength and power, and now it’s strength, power and movement efficiency,” Leinster’s Head of Athletic Performance, Charlie Higgins tells The42.

“If we’re playing on a Sunday, on Monday they come in and do lower-body weights. Tuesday they’ll do upper-body weights. Thursday they’ll do either a power session or upper body weights. Then anyone not playing on the weekend would have an extra session on the Friday.”

The Australian continued: “From a speed point of view, we have speed and mechanics on a Monday, conditioning on Tuesday and more speed is done on a Thursday. Anyone not playing will do extra conditioning on the Friday.”

During the summer, the gym programme for the Leinster senior squad remains largely similar, although some players do focus more on bulking up in the off-season.

“The pre-season window is 12 weeks in Australia, whereas here it’s pretty much six to eight weeks so you’ve got a limited amount of time. It actually doesn’t differentiate that much.

“We focus in the initial part of the off-season on getting guys a bit bigger and then pretty much it’s a strength focus with power. Based on the needs, some blokes are looking to put more size.

“You’ve got your squat, your bench, your deadlift, your chin-up and then any Olympic-type lifting. They’re pretty much the staple exercises of any strength and conditioning program. They’re the exercises that have stood the test of time so I don’t know why we need to deviate away from them.”

An advancement in technology means teams like Leinster can monitor the workload on the players to help predict when someone is in danger of picking up an injury or illness. Furthermore, flexibility and proper recovery are key components of injury prevention and ensuring players are at their best for the next game or training session.

“We have a thing prior to training called ‘movement prep,’” says Higgins. “That’s a preparation session where we self-release and foam-roll, and prescribe flexibility and movement.

“It’s one thing to come in and say you’re alright, but quite often guys don’t know they’re sore or tight until they start moving. So we do that before every field session so we have 30 minutes dedicated to movement and prepping for training.

“That’s before they get on field. Then they have another 20 minutes of warm-up before they can start training. The whole process before they start the rugby is about 50 minutes of prep.

“For recovery, number one is sleep and nutrition. We have a nutritionist who prescribes meals for players when they’re away. We’ve also got food catered for at the facility. We use icings, flexibility, movement. There’s no one answer to optimum recovery so we jump between all the different variables.”

Naturally, strength and conditioning ties in quite closely with nutrition. Catherine Norton, who was Head of Performance Nutrition at Munster from 2013 to 2016, typically sat down with the strength and conditioning staff, the Head of Athletic Performance and coaches before deciding on diet plans for individual players.

“It’s a multi-disciplinary decision. They’d ask, ‘what weight do we want a player to be, what’s the justification for it and how are we going to go about getting him there.’

“Then, the strength and conditioning team and the athletic performance teams would devise their programmes and I would devise individually-tailored nutrition plans to support each player’s target.

“The easiest thing to do is split nutrition into the couple of different components. The first component is nutrition for wellness, the second layer is their readiness to train and how they prepare in terms of fuelling before and recovering afterwards.

“The final layer is the preparation for competition. There would be quite specific nutrition recommendations that go into place and strategies we’d use on game day to support the physical demands of the match. And also to ensure they recover well because more often than not it’s a short turnaround to the next game.”

The Munster players use an app on their phones which gives them instant access to information on meal planning, food shopping and how to put quick meals together.

“The players were coming back to me saying, ‘I was in the supermarket and I was looking for what I’d cook and I’d open the app.’ It was something they were using all the time.

“They definitely do find it beneficial to have that kind of information at their fingertips. I suppose it’s just the way the world is changing – that people are a lot more reliant and much more likely to look to their phone for inspiration for what or how they should cook or buy, rather than sitting down to open a cookbook.

“There was an injured player who recovered quicker and attributed a lot of that success to nutrition. Once it comes from the players that there’s benefit to be derived from this kind of education, then they buy into it.

“Tommy O’Donnell is a great role model to hold up. He has a sports science background so he has some of the underpinning knowledge. Among the younger guys the likes of Dave Johnson or Steve McMahon were always great for coming up with new ideas and trying new recipes.”

The Munster players are being constantly screened and, Norton says, the management put a great deal of importance on those results.

“Every morning as soon as they step into the gym in the High Performance Centre in UL they’d be checking their weight. Every fortnight we’d be checking hydration status. Every six weeks we’d do assessments of body composition, or Dexascans, to check how much of them is fat mass and lean tissue mass.

“There’s a lot of value placed on those measurements by the coaches and management. They’re seen as indicators of how serious a player is taking the targets that are set, as well as how they’re performing on the pitch obviously. They’re good metrics to use as to how well that player is progressing.”

In addition to the raw speed and strength the game requires, mental preparation is another string to the bow of the modern player. Cormac Venney is the owner of HIPerformance Consultancy and has worked closely with the Ulster Academy since the summer of 2015.

“We very much multi-disciplinary, so we’d be working alongside the S&C, the coaches, physios, nutritionists,” he says. “We do one-to-ones with certain players, we do group-based stuff, and we go to games, observing a matches and integrating our service during training.

Venney uses sports psychology to help the Ulster prospects achieve optimal performance on the field.

“We look at the ability to recover from mistakes, self-management, self-awareness, communication, leadership, ways of enhancing confidence, ability to perform under pressure and also making sure there’s fulfillment and enjoyment there.

“We’d also be big into creating certain values, standards and an identity. The players understand what they stand for and who they are. This would be player led.

“For example, the Ulster Academy players suggested one of the things they wanted to stand for was humility. So over Christmas we took them out and did some charity work with the homeless of Belfast so they were able to live that value.”

Body language, particularly after a mistake, is another factor players are learning can have negative impact on performance on the rugby field.

“One of the things we’re big into is recovery from mistakes. Often what happens is a guy makes a mistake and a knock-on affect could be another mistake, because they’re hanging on to a previous mistake and not playing in the present.

“We try to get them to have the ability to get back into the moment. It could be identifying triggers that work for them, that’s what we work at in one-to-one sessions.

“We’ve done it in group sessions as well, where we’ve used video to highlight to the players – ‘Look at our recovery here, look at our body language. The knock on effect is another mistake. Is there a better way of recovering from that?’

“Also if you’re playing a game and you see the negative body language from the opposition, that can give you a boost as well. So it’s being mindful of that.”

Venney is teaching the young players to assess their performances with a more positive outlook.

“The big thing I’d find with players is their perception of things and how they choose to think about things.

“If you ask them how did they perform here, they could list you a load of negatives, but where’s your positives? It’s trying to rationalise that, the three or four things they’ve done well, then looking at an area to improve upon and ask, ‘how do we do it?’

“So we’ve have group-led things where they put in place group triggers to bring into training. Then we bring that into matches. We take it from video, to group discussion, to training, to a match. The idea is, under pressure we’ll resort back to habit. You create your habits in training. We want this to be their automated processes.”

“How they’re choosing to perceive things, how they’re choosing to talk to themselves. That internal dialogue and self-talk is very, very important.

“Inner drive to succeed is important. We expect high levels of commitment to engaging in what it takes to bring the best you can be.

“People say players either have it or they don’t; I don’t buy into that. I think it’s much more than that.”

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!