THERE WAS A photograph, printed across four columns in The Irish Press on Monday, July 30th, 1956, the morning after the Ulster final, that brilliantly illustrates the changing of the guard.

It shows the Cavan goalmouth, at the town end of St Tiernach’s Park in Clones, with an umpire reaching for a green flag and Tyrone goalscorer Donal Donnelly, wearing number 12, swaggering back to his position, his head cocked to the side as he surveys the crowd, who have encroached on the sideline.

On the left is Cavan goalkeeper Seamus Morris, helplessly panned out on the turf. To the right is full-forward Frank Higgins, airborne, as he follows up Donnelly’s shot, lashing the ball into the roof of the net again in celebration.

And in the middle is a Tyrone supporter, who has broken clear of the rest and raced on to the pitch with an arm and all five fingers out-stretched seeking the hand of Donnelly, who is impervious.

That championship had started well for Cavan. At half-time in Casement Park in the quarter-final, they had been level with Antrim but moments after the restart, Charlie Gallagher hit the net from 30 yards and Cavan went on to coast home, 3-15 to 2-4.

With his brother Brian standing out in a new role at left half-back, Cavan had good reason to be confident about retaining the Ulster title and more – for one thing, in Charlie, they seemed to have found that new, young forward they had been seeking the year before.

“Star of the attack,” said the Anglo-Celt, “undoubtedly was Charlie Gallagher, who played a brilliant game throughout; indeed his conduct on the field and whole approach to the game could profitably be copied by both friend and foe alike.”

Remarkably, later that evening, the Gallaghers played a second match. A large crowd from Cootehill had journeyed north to take in the Cavan game and then a challenge match against Antrim champions O’Donovan Rossa, who included in their ranks Down star Kevin Mussen. The Celtics won it, 1-11 to 3-2.

The semi-final was against Armagh, Cavan winning by 1-9 to 1-5 in Castleblayney, during which Brian Gallagher’s goal from a 45-metre free-kick – clipping the underside of the crossbar on its way – set Cavan on their way in a match that “had practically everything except good, clean football.”

“Any boxing coach looking for potential championship material would have found this game rewarding,” wrote Tom Cryan – who later found fame covering the fight game, particularly Barry McGuigan – in the Press.

And then came the final and Cavan’s world came crashing down.

****

“Under the high hill that makes a natural banking for the football field in Clones, thousands of Tyrone people went wild with joy yesterday – and with good reason,” began a colour piece in the Press.

“For the great barrier had been leaped. The 15 blue-jerseyed men who stand between any Ulster team and Croke Park had been beaten….

“Every Tyrone man secretly but fearfully hoped for victory. The man who sat beside me said he hadn’t slept a wink in a week.”

Cavan had been destroyed, the Red Hands swatting them like flies. Tyrone were ahead by a point at half-time and as torrential rain fell in the second half, they dominated, eventually winning by 3-5 to 0-4.

“At one stage,” read the report in The Ulster Herald, “I saw Phil ‘The Gunner’ Brady and Seamus Morris exchange glances and Morris shrugged his shoulders in a questioning attitude, as much as to say ‘What is really wrong?’”

In the Press, Cryan was scathing.

“Brian Gallagher, one of Cavan’s leading lights against Armagh, was probably the biggest disappointment of the day. Neither he nor his brother, Charlie, at half-forward, were anything like the force they were in Castleblayney.”

It was an earth-shattering result. Tyrone had never won an Ulster senior or junior title before; not even a McKenna Cup. That they managed it in such style and against Cavan – “Cavan routed as never before,” screamed one headline – made it almost unthinkable.

The Tyroneman’s Association in New York later brought the team across the water for two weeks, feting them at banquets and dinners and organising matches in Gaelic Park and the Polo Grounds. Another box ticked, another infringement on to a domain that had been Cavan’s and Cavan’s alone.

“We thought we were gods,” Tyrone’s 19-year-old captain, Jody O’Neill, would recall.

“I’d been to Dublin, I’d been to Belfast [but] I didn’t know what the world was like.”

O’Neill had a vivid memory of a Monday morning in 1946, the day after Cavan had hockeyed his home county in a championship match by 8-13 to 2-3. Jim Devlin, the legendary Tyrone full-back who was later murdered during the Troubles in 1974, was at the counter in his grocery shop and asked O’Neill and two friends what they had thought of the previous afternoon’s match.

“He reached over the counter and grabbed me by the pullover until we were nearly nose to nose and he said ‘O’Neill, as long as you play football or watch football, remember this: forwards win matches’.”

Nine years on and O’Neill, still a schoolboy, was playing alongside his hero. Tyrone ventured south for the All-Ireland semi-final against Galway with a spring in their steps with the rousing words of ‘The Gunner’, who had spoken to them in the dressing-room after the game about doing the province proud, still ringing in their airs.

Devlin was to mark the iconic Frank Stockwell and, the night before, in Barry’s Hotel, told anyone who would listen that he would hold the Tuam man scoreless. Within earshot was Galway’s Sean Purcell, a future Team of the Century full-forward, who asked Devlin if he would care to put a wager on it.

A fiver was produced and Purcell matched it. The next day, Stockwell failed to score but in the raucous aftermath of Galway’s 0-8 to 0-6 win, the bet was forgotten. Decades later, at an event in Dungannon, Purcell would chuckle that he still had Devlin’s five-pound note at home, framed.

For the Gallaghers, it marked the end of a horrible few months. In May, their brother, Fr Frank, had taken ill in England.

Frank and Charlie, despite the age difference, were close. Frank had been ordained a priest a couple of years earlier and was posted to a parish in the town of Longton, near Stoke-On-Trent. He became sick, a kidney complaint, and came home to recuperate but he would never return.

On 5 May, the family borrowed a television set and Frank was well enough to watch the FA Cup final – Manchester City beat Birmingham City, the game in which the winners’ German goalkeeper Bert Trautmann broke his neck and played on.

But his condition drastically worsened. Two days later, at just 30, Rev Francis De Sales Gallagher – named after the patron saint of writers and the deaf – breathed his last.

His youngest brother took the death badly. The funeral was one of the largest ever seen in the area, attended by 56 priests and members of the Cavan team, including Mick Higgins and other All-Ireland winners.

Gallagher would never forget his brother. “Dad wasn’t religious but he would always say to me ‘Frank will be looking out for you’,” remembers Charlie’s daughter, Louise.

***

Few then knew but 1947 – the year of Cavan’s greatest triumph – would mark the beginning of the end of their stranglehold in Ulster. All-Ireland titles in 1937 and ’38 and an All-Ireland final appearance by a team featuring Tom Maguire and a 16-year-old Jim McDonnell in ’52 aside, Cavan had flopped in the minor grade as the northern teams grew in strength.

On September 14, 1947, as Cavan were preparing for their senior final in the Polo Grounds, Tyrone defeated Mayo by a point to bring the All-Ireland minor title to the Six Counties for the first time. The following year, they retained it against Dublin and the year after that, Armagh won it for the first time, beating another aristocrat in Kerry.

The northern teams were on the rise.

“Cavan were getting it tight enough in Ulster from ’46,” recalled Johnny Cusack, corner-forward on the 1952 All-Ireland winning team.

“Antrim and Armagh and Tyrone and those teams were coming up. From 1927 on till the mid-forties, it was only a matter of walking out for the Ulster final but that was starting to change.”

That year – 1946 – was a particularly successful one for the ‘other’ Ulster counties, with Down, from nowhere, winning an All-Ireland junior title, St Pat’s College from Armagh claiming the Hogan Cup and Antrim stunning Cavan in the Ulster senior final.

But the biggest change of all came a year later, by way of a decision which had nothing to do with football. Winston Churchill had been shunted out of power and the Labour government brought forward a radical wave of progressive, liberal reforms. For the first time, there would be a welfare state.

The Butler Act in England and Wales in 1944 and the Education (Scotland) Act of 1945 were followed by the 1947 Education Act in Northern Ireland, introduced by the Stormont Government amid fierce Orange Order and populist Protestant opposition. In increasing funding to the Catholic school sector, the legislation, according to Professor Graham Walker of Queens University, “was of a piece with the social reform ethos of the times, and the determination to build a more just society out of the trauma of war”.

“The Act,” it has been documented, “required the building of secondary schools, including top quality sports facilities, for pupils up to the age of 15 and the employment of specialised PE teachers to instruct them. For the first time Gaelic games were included on the course syllabus for students and the game enjoyed equal status with other activities.”

Suddenly, Catholic children had access not only to free secondary education but to expert coaching in Gaelic football when they were at school. By the mid-to-late 1950s, a generation of educated Northern nationalists were reaching adulthood and beginning to enrol in third level education in large numbers for the first time. While they had not been completely liberated, the nationalist population of the North had been given the means to further themselves.

Gaelic football was the sporting pursuit overwhelmingly favoured by this section of society and as the game quickly began to boom, so did the interest levels; in 1961, a year before RTÉ made the leap in the south, the BBC would become the first station to televise a Gaelic football match.

So, when 1957 dawned, Cavan had been deposed and were now faced with a challenge, within Ulster, the likes of which they had never met before and for which they were totally unprepared. The storm was coming and unsurprisingly for Cavan, things would get much worse before they got better.

***

In 1957, Tyrone retained their Ulster title. Cavan had a patchy National League campaign, with Brian Gallagher their best player and Charlie, despite some injury problems – a rare occurrence in his career – nailing down a place at wing-half-forward.

In April, they lost the league semi-final to Kerry by a point at Croke Park but had a good warm-up for the championship a fortnight later when beating Tyrone; Charlie enjoyed his “best game to date for Cavan” in a one-point win to mark the opening of new pitch in Tempo, Co Fermanagh.

Monaghan were comfortably beaten, 1-12 to 1-5, in the Ulster quarter-final but Cavan were stunned by another of the nouveau riche northern teams, Derry, in the semi-final at Dungannon

The Celt bemoaned the extra time added on by the referee, with the only possible explanation, they reckoned, having been a delay while the ball was retrieved after Gallagher “kicked it into the next field while attempting a score”.

It mattered little. Sean O’Connell, Gallagher’s future team-mate with Ulster and Ballerin, kicked the winner and Derry held on, 1-9 to 1-8. For only the second time in 35 years and the first since 1938, Cavan would not take their place in the Ulster final.

Derry, who had only had an organised county board since 1933 – by which time Cavan held the province in a vice-like grip and had already put in place a county grounds – reached their first Ulster final in 1955, losing to Cavan. Now they were back and would face Tyrone in an all-Six Counties clash.

The times they were a-changing.

***

In ’58, it took Cavan three games to get over Monaghan in the first round. Making hard work of Monaghan was notable in that, while the Farneymen had won the previous year’s All-Ireland Junior Championship, they hadn’t beaten Cavan in the Senior Championship in 28 years.

They drew first day out in Clones in a match the Celt reckoned “must rank high on the list of the worst games of football played under a championship tag”, where “dog rough, useless, mulish play was the order of the day”.

In the Independent, legendary writer John D Hickey commented that “for the most part, the ball was merely of secondary importance. The players had worn themselves out in the orgy of ankle-tapping, elbow-slinging and jersey pulling and the hundred and one tricks which all the too-old, the unfit and the sub-standard footballers know and use when the opponent is getting the better of things”.

Poet and playwright Tom MacIntyre saved two Monaghan penalties to force a replay, which wasn’t much better; the sides drawing 1-5 apiece at Breffni Park on a day when the Tavey brothers, John and Paddy, from Donaghmoyne lined out for opposing sides. Extra time, as was the norm, was not played because the referee had retreated to the dressing room to get away from “a mob, hundreds-strong”.

The third game was fixed for Casement Park on a Sunday evening and this time Cavan clicked, building up a 0-8 to 0-1 half-time lead and eventually winning 0-14 to 1-6, with Charlie “re-establishing himself in no uncertain manner, scoring four great points from play”.

On the same afternoon, Down came out of the ether to topple Tyrone by 1-9 to 0-2. With the champions gone, Cavan could have fancied their chances but Derry lay in wait again the following Sunday.

Charlie landed the first two scores of the Derry game – he would finish with 2-3 – but what was described as “a tragedy of errors” befell Cavan, with Brian Gallagher hitting the post with a penalty; Seamus Conaty striking the crossbar and, in the end, Derry – inspired by Player of the Year in waiting Jim McKeever – running out 4-7 to 3-6 winners.

“I came on to the team in ’45 and didn’t win an Ulster title for 14 seasons, until 1958,” remembered Roddy Gribbin, Derry’s player-manager that year.

“That’s why I appreciated it so much. I played for that long and Cavan would usually pip us to the post, every year.”

The Derrymen would go on to beat Down in the Ulster senior final. History was made. In the curtain-raiser, however, Down gained some consolation, as their “crafty forwards”, ominously made hay in hammering Cavan by 3-9 to 3-1. It was Down’s maiden Ulster minor title.

The underdogs were biting back, hard. And for Cavan, there was more where that came from.

Another Derryman, Paddy MacFlynn, had been part of the GAA’s official delegation that had gone to the Polo Grounds. He knew the power and the majesty of Cavan and he knew things were changing, too.

“The blue jerseys of Cavan… There was nothing in Ulster to even compete with them,” he said.

“Antrim were the first team to really put it up to them in the mid-’40s. Then Down came…”

***

Ulster final day was and is a pilgrimage, the masses of Ulster Gaels descending on Mecca, usually Clones.

The Ulster final was generally played on the third Sunday in July. The sun shone. Supporters left home early to get a run at the day.

“It’s a fair, a festival, a Fleadh,” MacIntyre would write a few decades later, after attending the latest instalment as a supporter.

“In the crush and scramble I saw people I hadn’t seen for decades. The fair resembles a big wedding, a grand funeral… There should be a painter present, I muttered.”

When MacIntyre was playing in those matches, the event was much the same. Every nook and cranny of the town was crammed. The colour remains the same; only the colours change.

In Clones, the locals showed an entrepreneurial spirit. There were what was called a ‘meat tea’ to be bought, from makeshift stalls in alleyways and entries – sustenance for the journey home.

On such occasions, fleeting moments can change the course of a sporting lifetime. A goal here, a tackle there. A split second decision.

When Tyrone lifted The Anglo-Celt Cup for the first time in ’57, after dismantling Cavan and dashing the hopes of 19-year-old Gallagher, their captain Jody O’Neill, the same age, had brought the old trophy down the town, through the throng, to the Creighton Hotel on the bottom of Fermanagh Street. There he met his father and the old man’s friends.

“There was an archway underneath the hotel and there were hay bales. My father was there with a group of Coalisland people and I brought the cup down and of course they wanted to take a drink out of it.

“And one of the boys said to me ‘come on, Jody, you have to take a drink’. I looked over at my father and he said ‘whatever you like son’. I didn’t take it…”

Until the late 1950s, many travelled by train. Clones was a vital railway hub and that helped build the tradition whereby St Tiernach’s Park would host the biggest games. By the end of the decade, though, roads had improved and cars were becoming more commonplace. Railways, north and south, were closing dow, the sleepers destined to rot in the ground and be overgrown by weeds.

With personal ownership of cars increasing, inter-county teams could streamline their preparations, meeting at central locations to train during the week. On and off the field, the late 1950s was a time of radical change.

Footballers of Cavan had come to see the Ulster final, and lifting the cup at the end of it, as their birthright. But by the dawn of 1959, Charlie had been a first-choice senior footballer for three championships and had yet to pick up an Ulster medal; his only final appearance ended in a chastening 10-point defeat.

Charlie was the anointed one, the forward who was destined to keep the colours of the tribe flying for another generation. It wasn’t supposed to be like this.

Gallagher was making his name with UCD and had been carving up defences in the green and white hoops of Cootehill since he was a boy but in the royal blue and white of Cavan, progress had stalled.

By the dawn of 1959, alterations had been made to the landscape.

Cavan, though, eased to a handy 2-9 to 0-4 win over Donegal in their championship opener in Ballybofey. A last-minute Brian Gallagher point earned a draw against Armagh next time out in a match the referee accidentally blew up three minutes early.

Cavan won the replay, 1-9 to 1-7, with the Gallaghers scoring 0-3 each and James Brady the remainder.

“To Charlie Gallagher,” wrote Hickey, “goes a special word of praise for what he accomplished, though pitted against a man of the calibre of John McKnight.”

On the other side of the draw, Down had confirmed their dominance over Tyrone by trouncing them in a replay. The Mourne men’s rise had been well-flagged and Cavan were wary.

The Celt sports editor, PJ O’Neill, however, could only see a win for the traditional heavyweights. O’Neill, a Wexford native and brother of Polo Grounds referee Martin, had revolutionised the sports pages of the newspaper, in common with what was going on around the country. Interest in Gaelic games was at an unprecedented level – a record 90,000 would attend the following year’s All-Ireland football final – and colour GAA magazines were flying off shelves.

Newspapers were responding; even the staunchly unionist Belfast papers were beginning to carry limited GAA coverage.

O’Neill, who would introduce the Sports Page Arena section to the Celt – effectively an opinion column and soapbox for fans with something to get off their chest – was not one to shy away from calling it as he saw it.

He commented that “if tradition counted for everything, then the match is as good as over” but noted the “deadly lethargy” that had plagued Cavan teams in the previous handful of championships.

“Cavan have had a lean time in the football world,” he wrote, “and the up and coming northern teams have gained in confidence with Cavan’s downfall.”

One had to go back to 1915, when Cavan won the title after a seven-year gap, for the last comparable famine, he noted. But he expected Cavan to win and restore some pride.

The enthusiasm still comes through in chairman TP O’Reilly’s quote in the same article:

“The spirit is excellent and we are definitely out to take the title back to Cavan.”

O’Reilly’s old All-Ireland winning team-mates Hughie O’Reilly and Joe Stafford, along with Higgins, were part of the backroom team and Cavan moved their training base from Virginia to Bailieborough, where they prepared rigorously.

The Evening Herald, which carried a photo of Gallagher, expected Down to mount a strong challenge but, in common with the other papers, did not foresee them claiming a first provincial senior title.

In the end, the Celt’s headline the following week — “Too bad to be true” — told its own tale as Down won their first Ulster title by an astonishing 2-16 to 0-7.

Peadar O’Brien in the Press described Down’s victory as “thoroughly deserved, utterly convincing and wonderfully popular”. It was Down’s first Ulster title and some of their supporters among the 30,000-strong crowd climbed the goalposts, O’Brien recorded, in celebration, placing a Down flag at the peak.

As a metaphor, it could not have been more fitting. In sweltering heat, Cavan’s status as a footballing power seemed to have evaporated while Down, tracksuited and in black shorts (both firsts for a GAA team) tore them to shreds.

At half-time, Down led by 1-10 to 0-2. By the end, the Gallaghers had scored all of Cavan’s total but it mattered little. “Ninety per cent of the Cavan players,” the Celt added, comically, “were literally stuck to the ground.”

For Down, even though they would lose the subsequent All-Ireland semi-final to Galway, things were just starting. The magnificent Sean O’Neill, at 19, had won an Ulster medal at the first time of trying. The 1960s beckoned and promised to be glorious.

On the undercard, the Cavan minors defeated Antrim in the Ulster final. A glimmer of hope, maybe, but the golden age now seemed further away than ever.

Winter was coming and on Christmas Day, Charlie would turn 22. For the first 17 summers of his life, Cavan had won 16 Ulster titles. Since he had come on to the team, they had won none.

He and Brian, Tom Maguire, James Brady and Noel O’Reilly, as usual, shared a car for the trip back to Dublin. On this occasion, it was a sombre journey while, up the road, the party was only starting, in every sense.

“I was fortunate in 1959,” O’Neill would recall, “because I got on the end of a rocket that just took off.”

For Cavan, things would never be the same again.

“Down gave us a hiding in the Ulster final and went on to play Galway in Croke Park in the All-Ireland semi-final,” recalls future star Gabriel Kelly, who attended that match.

“I remember coming out of Croke Park and a fella said: ‘Oh, that Down team is a flash in the pan, you’ll never hear of them again.’ How wrong he was.”

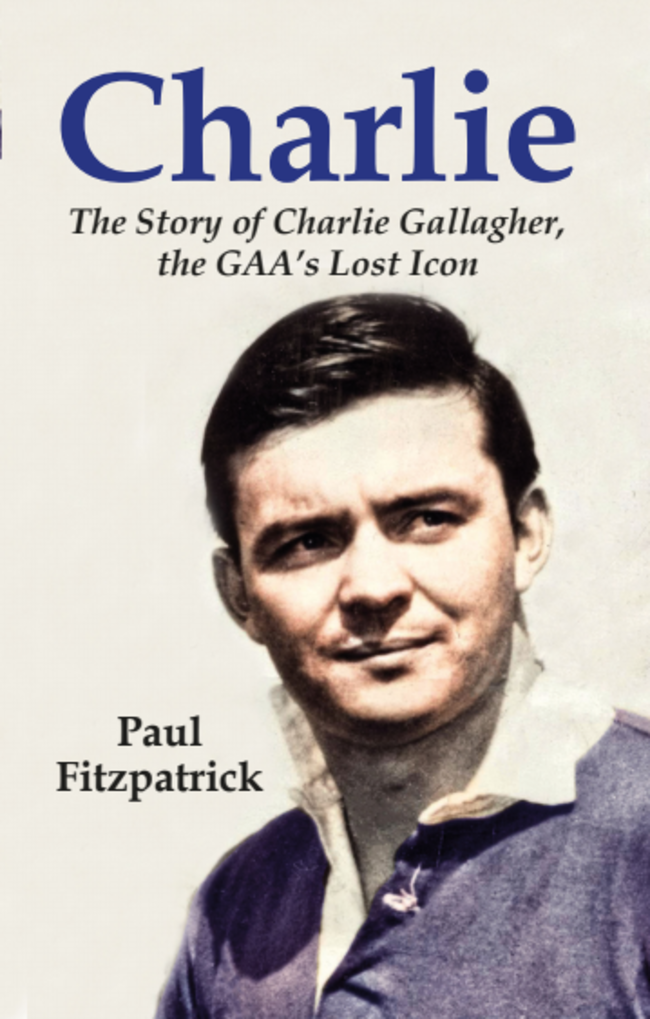

Charlie by Paul Fitzpatrick is published by Ballpoint Press and available in bookstores and online now.