IT WAS THE morning of New Year’s Day in 2008. Former Ireland rugby international Peter Clohessy was engaged in one of his favourite activities — fox hunting.

He loves the thrill of hunting, even if he never wishes to see a fox caught or injured.

And while ‘The Claw’ was out hunting in the middle of the fields of Tipperary that day, he spotted a rider laying prone on the ground. The rider in question was a 13-year-old girl named Aoife, who had fallen off her pony and been rendered unconscious as a result.

Another female rider arrived on the scene and urged Peter not to move her neck. “F**ck her neck… she’s not breathing!” he responded tensely.

Peter sensed that the injury could be life-threatening, fearing the girl may have swallowed her tongue. He’d heard about these situations before, but never experienced them first hand. He knew Aoife’s mouth needed to be opened, and eventually succeeded in doing this, after it had initially been firmly closed shut. Suddenly, following this action, she started breathing again.

The emergency services later arrived in this secluded area and took Aoife to Cork University Hospital, where she was diagnosed with a severely fractured skull. Nonetheless, she survived ultimately and experienced a full recovery.

Had it not been for Peter’s intervention, or had he gone with his initial instinct and stayed at home that morning, the doctors confirmed that Aoife almost certainly would not have survived. But Peter has barely mentioned this heroic act since.

“It was that evening before he told me,” says Anna Gibson-Steel, Peter’s wife and author of a recent biography on the former Ireland international, A Life with Claw: The Peter Clohessy Story. “The girl’s family rang and it was reported. But he’s actually incredibly humble about these things despite his abilities.”

(Peter Clohessy pictured in the Ireland team photo in 2002)

In many ways, the passage feels key, as the book is as much an insight into Clohessy’s character as it is a celebration of his achievements on the rugby field — a point Gibson-Steel reiterates.

“For me, it was always about the stories and the characters,” she tells The42. “That was the uniqueness of it. It gave an insight into him that certainly couldn’t be achieved by a ghostwriter. Really, the book is about his personality and the phenomenal character he is — to demonstrate how he behaves in certain instances. I don’t think a ghostwriter could have fully captured that.

“It’s because I knew the subject intimately [that I captured it]. But I would not be capable of making up a fairytale for the children at bed time. I’m not a writer at all — all I was doing was having a conversation about life experiences.”

Clohessy, Gibson-Steel admits, was of little help during the research process, owing to his hazy recollection of most events. Fortunately though, she had always been in the habit of keeping newspaper clippings, from Clohessy’s early days playing club rugby to his retirement, not long after the onset of the professional era, meaning she had an entire scrapbook full of memories at her disposal by the time she came to write the biography.

And while many sports stars and their collaborators write books for cynical reasons such as money or score-settling, for Gibson-Steel, the decision to tell their life story was conceivably borne out of altruism.

“I did it,” she says, “for the children.”

The project was prompted, in particular, by their eight-year-old son. His school friends had shown him a video of his Dad scoring a try — it was the first time young Harry had ever seen Peter playing rugby for Ireland.

“He was very animated and I said: ‘But you’ve seen Daddy play before,’ and he said ‘I’ve never seen Daddy play,’” she recalls. “At that moment, it dawned on me that there was a whole part of Peter’s life that was over before he was born. It’s not like you sit around talking about it.

“So I sat him down to watch a video and he actually got quite upset. He said: ‘I never got to see Daddy play.’ I could show Harry 40 videos of his Dad playing matches, but that was never going to [satisfactorily] examine his rugby career.

“They’re incredibly connected, but the book gives him an insight into what would have gone on before. I wanted our son to see Peter as a man rather than as a Dad, which are different things.”

Yet while the book may have been written for deeply personal reasons, it is far from inaccessible to the average reader. In fact, the feedback Gibson-Steel’s received has been unanimously positive — an impressive feat for someone who had never written a book previously, and whose English teacher, she admits, would balk at the notion.

“People from all over the country have been sending me emails,” she says. “There was one guy who was initially irate that a female would write a rugby book. I understand all of that. I knew that would be one response going into writing it.

“But he then said the book was fantastic — one of the best sports biographies he’s ever read. So it was doubly rewarding for me, to receive praise and to break through those kind of belief systems that people might have.”

As well as encompassing countless amusing anecdotes, A Life with Claw also provides a fascinating take on the major changes rugby has experienced since the dawn of the professional era — a time period that coincided with Clohessy’s career at the top level. Yet for all the positive developments this change instigated — more money, better quality of rugby etc — from the Munster legend’s perspective, the transition was bittersweet.

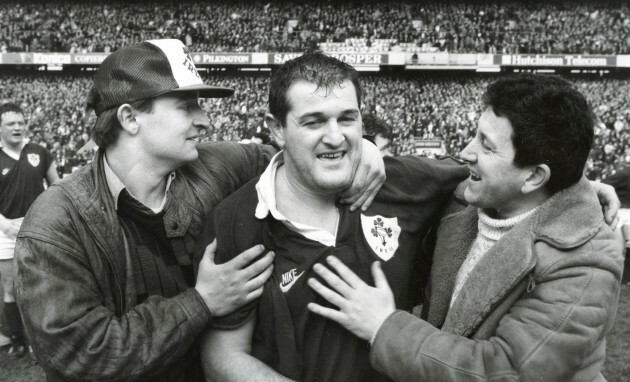

(Peter Clohessy, during the early days of his rugby career, is congratulated after a victory against England)

“Did he have much fun in the professional era? No,” Gibson-Steel acknowledges. “He enjoyed the fact that the game got more skilful. He enjoyed playing a higher level of rugby. But off the pitch, and I’m sure all the players would say this, it was nothing like the fun they had in the amateur era.

“He wouldn’t swap the fun he had to be fully professional [now]. But it’s changed — it’s like anything. Rugby was a fun thing to do — kids would have [originally] gone into it for the social aspect.

“The connection between supporters and players has been lost [in the professional era]. Not that the players should drink, but the socialising and connectivity [is gone]. In becoming professional, there has been a disconnect with the public. I’d lament that, for sure.

“I think it’s what made mediocre teams phenomenal. Munster were a mediocre team in terms of talent compared to what the others were doing in the Heineken Cup in the early days. But their success was based on passion and that passion was an energy based on connectivity with those that were supporting it.

“The players were just the players — you went into the pub and they were standing at the bar. They weren’t harassed — they were having a drink and people would say ‘hello’ and things like that. But the other generation doesn’t know any different [to what they're experiencing now].”

Another way in which the game has changed immensely is evidenced by modern rugby players’ handling of the media. The education in the art of answering questions, which contemporary stars have become accustomed to, is a far cry from the much less savvy and far more casual attitude adopted by players of Clohessy’s generation.

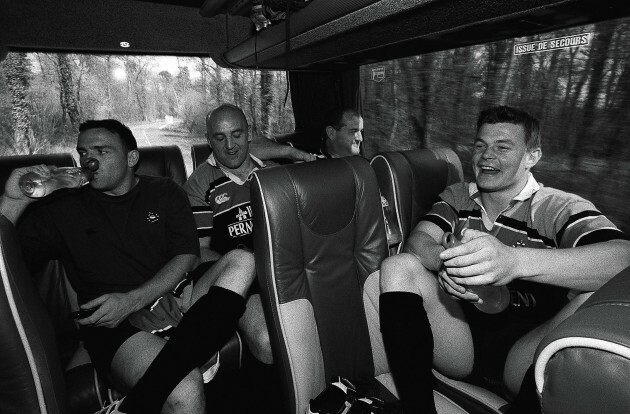

(Peter Clohessy having a laugh on the team bus with fellow Ireland internationals Rob Henderson, Keith Wood and Brian O’Driscoll)

“Since it went professional, players are protected from the media. But they’re also more exposed because of social media. Is it better or worse now? Probably worse overall, because they can’t budge.

“The media made Peter out to be a villain. He did what he did, he doesn’t deny that. But it was interesting how it was reported and interpreted. But they were different times — the media was run in Dublin and there was very much a divide in terms of rugby there and the rest of the country. You had all of that stuff going on, so politically, it was different. It’s not the same now, so it’s hard to say.

“I often now hear the media saying that they can’t access the players. In Peter’s day, there’d be no such thing as being coached how to do an interview. You pretty much talked to the journalists that you trusted. It’s very different now. Is that part of it better? I think so.

“Just because someone’s good at rugby doesn’t mean they’re good at giving an interview. They’re different skills that different personalities might not have. And to be judged on that is always quite harsh.”

Gibson-Steel also feels the style of reporting has changed, partially owing to Munster’s success, with less media bias evident as a consequence.

“The filter has levelled in terms of rugby reporting, but that’s probably down to Munster’s success. The fact that they’ve become so successful meant that a light had to shine on them. The media had to pay attention to Munster, so that’s probably part of [the reason for] the balancing act.”

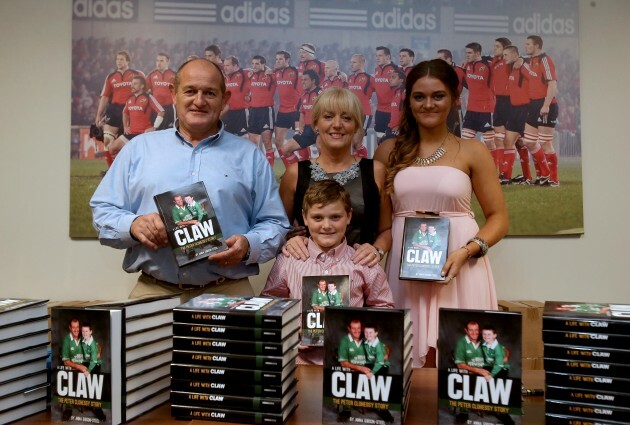

(Peter Clohessy, Anna Gibson-Steel and their son Harry and daughter Jane pictured at the recent launch of A Life with Claw)

Yet for all its interesting stories and insightful points on topics such as rugby’s switch from amateur to professional, what really distinguishes A Life with Claw is not the story itself, but the perspective from which it is told.

Few, if any, sports biographies are written from the point of view of an athlete’s other half, but with her mix of perceptiveness and comprehensive rugby knowledge, Gibson-Steel does a fine job telling the story of Clohessy’s remarkable career, and her own important place within this extraordinary life.

Moreover, in writing the book, Gibson-Steel deconstructs some of the stereotypes frequently associated with athletes’ other halves, or WAGs as they’re commonly referred to.

And contrary to popular belief, supporting a famous sports star through this often turbulent journey is far from an easy ride at the best of times.

“The book gives a window into a world from a different point of view. We’re well aware of the public perception — [they think] a WAG’s life is a great life. In terms of the practicalities of it, it’s actually a really tough supporting role, particularly when kids come along. If you’re trying to maintain a marriage, raise children, get the children to games or minders… It’s not glamorous — not by a long shot.

“It certainly has its advantages — there are no two ways about that. But do they outweigh everything else? I just wanted to level people’s perception of it, or give them the reality, rather than this concept of what it might be.”

And watching games is presumably a drastically different experience to that of the average spectator. Did she, for example, constantly worry about her husband suffering a serious injury?

(Anthony Foley gets congratulated by Peter Clohessy following Munster’s Heineken Cup win in 2006)

“For me personally, I never worried about him getting injured in a match. My only concern was that he’d go over that try line. My professional opinion is that if you worry about things, you’ll attract them to you. But I’d know within five minutes of the match about the humour Peter was in and the attitude he’d have towards it. Then I’d either relax or hold my breath.

“I can’t speak for all partners — maybe some are nervous about injuries, I don’t know. Perhaps, it’s because I went to a rugby school and I’m used to it [so I'm relaxed]. Maybe if I came to the game later in life, then I might see it differently, but when you’re 14 and you’re watching the game, you don’t think about that.”

Over a decade on from his retirement, Clohessy now runs a bar and restaurant in Limerick, in addition to serving as a rugby reporter, while Gibson-Steel works at the Holistic Centre of Excellence — the only training college of its type for therapists in Ireland — which she established in 2011.

Furthermore, Clohessy has received just one offer to end his retirement, from Toulouse, just after he had hung up his boots in 2002, while on holiday in Kilkee. Initially rejecting their approach, he then reconsidered, but by the time he contacted them, the French club had already signed a new prop. Is this missed opportunity ‘The Claw’s’ one regret, particularly as Toulouse went on to win a Heineken Cup later in the season — a feat that narrowly eluded Clohessy over the course of his storied career with Munster?

“He doesn’t do regret in any shape or form — never did,” says Gibson-Steel. “He had retired [when Toulouse called]. It was a beautiful summer’s day, there were no commitments, no having to be anywhere…

“When the call came, he said ‘I wonder would I?’ I just said ‘why did you give it up in the first place?’ You could have kept playing with Munster. Then when we got home and everyday life sunk in, he said ‘it might be a nice thing to do’. But he wasn’t bothered [when it didn't happen]. Peter doesn’t look back.”

More info on A Life with Claw: The Peter Clohessy Story can be found here. Hardback copies of the book can be bought in Small Claws and Crokers — Clohessy’s restaurant — in Limerick.