CON POWER EYES the morning’s visitor with a doubtful face.

He moves forward, stepping out from the rear view mirror into the fullness of his marked angular frame. Close up, his physical presence is striking. But Power’s expression quickly softens, conveying a warm character beneath the hard exterior.

“You can sit there all day but that gate won’t open,” he proclaims, suspicion displaced by kindness as he proffers the security code.

I offer him a lift, still unsure of myself. He considers it, responds after a beat: “No, I have my own transport.”

Already there is humour in the air. He moves to the main entrance and keys in the numbers that release the lock. A clink and I am out of limbo. The road is quiet between Moynalvey and Kiltale at this hour on a Monday. Derrypatrick is home to the Powers and Robert lives two back. Con follows me down.

Their family name is pedigree: Wexford originally and hothoused in Meath.

The bloodline can be traced to 1926. Patsy Power, Robert’s great grandfather, was photographed that year at the County Show in Enniscorthy. His credits as a breeder include Caughoo, Grand National winner in 1947. Con, Patsy’s son, competed locally in Point to Points and bred Barnes Park, who went on to win the Lincoln in 1951.

The 1970s brought international acclaim. Captain Con Power starred on the Ireland showjumping team that won the Nations Cup (and the Aga Khan Trophy) at the Dublin Horse Show three years running, 1977 to 1979.

Robert continues the tradition. On his watch, the Powers have reached the zenith of the National Hunt game.

Con is succinct: “As the fella says, he’s bred to do it.”

Three years ago, RM Power steered Sizing John to the Cheltenham Gold Cup. This week, the jockey known to punters as Robbie (and to colleagues as Puppy) returns to the blue riband race aboard another strong contender: Lostintranslation.

He might leave his sire in paroxysms of joy. Again.

***

Father is delightfully frank: “It’s about 10 times better watching Robert do it.”

Video captured raw instinct as Sizing John scaled the final hill at Cheltenham in 2017. Con bucked on the couch, flapping and yahooing, roaring on his boy.

“People spend millions and millions every year trying to buy a Gold Cup horse,” he details. “To see your own son winning… If you don’t get a kick out of that, then you’re in the wrong sport.”

Con’s dream of becoming a race rider floundered during teenage years. His nature, nurtured among horses and horsemen, turned against him.

“The only reason I went showjumping was because I was too big to be a jockey,” he recounts. “The year I did my Junior Cert, I shot up from being a handy size to being 6’2”.”

Ambitious from the start, Power sought a position where success mattered more than selling nice young horses. For that reason, he was unwilling to work in a dealing yard.

His search ended at a military parade: “The only man left was the Minister for Defence. 1972, I applied for the army and got picked. Then you’re 12 months as a cadet, training on The Curragh.”

Power inevitably gravitated to the equitation school: “First horse to ride every morning was at nine o’clock. He was tacked up in the indoor school and waiting for you.”

A good number, I suggest.

“Oh fuck, yeah,” he raves. “There was no mention of hardship. Before I was married and living in the Officers Mess, your bed was always made for you. And your boots were polished. Then I married Mag and that fucked all that up.”

At home, the Captain cannot pull rank. Mag is just as dutiful as her husband but never subordinate. She had no choice, not when Con suffered a freak accident that threatened his life. 1988 upended his family’s world.

“I got my fair share of falls and always came home hale and hearty,” he relays. “I went to a horse trials, on fucken foot, and didn’t come home for six weeks.”

Power curses his luck with typical mirth. But the consequences of that blow, inflicted by a horse running loose, are felt to this day.

“Since I had the accident, I can’t sit on a horse,” he says. “I had to give the brain surgeon a guarantee that I wouldn’t get another fall. And I had no interest in riding a horse for the pleasure of riding.”

A competitive instinct remains the core: “I never drove out my gate to go to a show just for the fresh air. I went to win the main class. I’m a competitor. Now, you win some, you lose some. That’s the great thing about sport. You have to be able to take the losses. We can all be great winners.”

Recent years have revealed a great winner in the shape of his son. But both men knew what quality was there all along.

“You have to have confidence in your own ability,” Robbie stresses. “You mightn’t be riding winners but you have to be confident that you’re doing the right thing. It’s not easy sometimes.”

Con emphasises a racing maxim: “Good horses make good jockeys. When he started off, he had a top-class 12.2 pony. He had the best 13.2 pony in Britain and Ireland. It was the best pony we ever had. He trusts the pony, the pony trusts him and I trust the whole operation. I’m a great believer in giving a kid confidence to make them believe that what they’re doing is right and go from there. You develop bad habits when you’re riding bad horses and then you’re killing the good horse’s instinct.”

All the senses are strained trying to succeed in this sport. And all authority belongs in the hands of the rein holder.

“I’m sitting in the stand and seeing strides down to the fence,” Con explains. “If he’s not seeing the same stride, I’m thinking: ‘Oh, Jesus.’ But that’s nature. I’ve no control. By nature, I’ve a good eye for a stride. That’s God given. You don’t learn that.”

His son takes up the topic: “Basically, you can spot where you want the horse to take off. Sometimes, it can work against you. If I’m rolling down to the fence and see a stride six or seven strides away, and I know I’m meeting it wrong and I go to change, I could lose momentum. If you see it early and you keep going, a stride might come up. Sometimes you might see too much. But, nine times out of ten, it is definitely an advantage.”

Beyond talent, mindset. What turns over inside the minds of these men?

“Several times you’d walk a course and it wouldn’t ride like it would walk. So you have to be able to alter right away,” Con relates. “The man who learned out of a book, if it’s not working out for him on horseback, is fucked.”

Robbie adds his perspective: “When you walk into a parade ring, the owner and trainer you’re riding for expect you to have an idea of what’s going to happen in the race. Now that can all change. But you have to have a fair idea, one, of how you’re going to ride your own horse, and, two, what’s going to happen in the race pace wise. Now it doesn’t always work out like that but you can’t just go and wing it. You have to do your homework.”

He sketches the typical routine: “It’ll take me half an hour, an hour max, to go through the races. When you’ve ridden a horse before, you definitely wouldn’t watch footage of it. I would just do homework on the race. It’s all in my head.”

Technology allows for easy revision.

“You can analyse it so much more than you could 20 years ago,” Con states. “There was no replay in my time. Nowadays there’s cameras everywhere. Generally, video wouldn’t have made any great difference for us. It’s more of a trainer’s weapon. If you’re truthful to yourself, you’ll know in your heart and soul what you did wrong.”

About the rider’s responsibility, Robbie is clearcut: “The trainer knows what’s going on at home and what his horse has done and how his preparation has gone. But he’s handing the reins over to you for the five minutes of the race and it’s your job to know what’s going on, on the racetrack.”

But every advance entails a new risk.

“Sometimes you can be too self critical and that’s a disaster,” Con asserts. “You have no chance because you’re afraid of everything.”

“That is a disaster,” Robbie quickly reiterates. “There has to be a stage where you take things into your own hands: ‘Right, Plan A is not working out. I can’t go the gallop that these are going. I’ll have to take my time a little bit and change.’ That’s where all the homework you’ve done goes out the window because the feel the horse is giving you is not what you were expecting.”

No jockey makes that journey unaided. Early in his career, Robbie Power learned a vital lesson from one of racing’s wise men.

“I remember going out to ride for Paddy Mullins,” he recalls. “I rode a horse called Bob What, my first winner as a professional, a big handicap hurdle in Leopardstown on Hennessy Day. Paddy never gave any jockey any instructions. He just told me: ‘Take your time.’ So, I took my time and the horse won. The next day, I’m riding him in Fairyhouse. We’re standing in the middle of the parade ring. The bell was rung. I says: ‘Well, Boss, what do you want me to do?’ There was no mention of any instructions: ‘Jaysus, if you’re looking for instructions I must have the wrong man riding him.’ He was right. I rode the horse and won on the horse, why did I need instructions? I should know what to do.”

Only experience could leaven what time had not then afforded. Success on the sport’s biggest days has earned him the right to rely on his own convictions: “I think when a jockey gets a reputation, trainers generally trust you more and leave you to it. It’s very rare now when I’m riding for Jessie [Harrington] or Colin Tizzard that they’d give you instructions.”

Conversation inexorably leads, with Cheltenham approaching, in that direction. Robbie Power surveys this year’s festival with a hopeful face: “Potentially, I’ve as good a book of rides as I’ve ever had. Fingers crossed, it’s going to be a busy few days.”

Tolerance for pain, if anything defines a jockey, might measure him best. When the topic arises, the Powers adopt the same stance.

Robbie sets the scene: “Last year, the Sunday before Cheltenham, I got a fall at Naas and landed straight down on my back. Doctor comes over: ‘Are you okay?’ I had a small bit of pain in my back: ‘I’m fine, Doc. Not a bother.’ I was going to let on there was nothing wrong with me. I was in awful pain then at Cheltenham. Came back on the Friday night. Went for an MRI scan on Saturday: two fractured vertebrae in my back, L4 and L5. If I had gone for the MRI scan on Sunday evening, I wouldn’t have been going to Cheltenham.”

Con is unflinching: “If you’ve no pain, you will ride. End. Of. Story. I got a fall in Hickstead one time and I actually dislocated my shoulder. I rode the next class with my shoulder dislocated. Then went to the doctor: ‘There’s something wrong here.’ He put me face down on the ground, and, CLICK. He gave me a few painkillers and I was fine. I rode the next day.”

This recollection resonates with his son: “I don’t ever remember riding feeling pain in a race. I’ll feel it after, when I pull up. All through Cheltenham last year I struggled getting out of bed in the mornings. Go to the physio. She had to help me off the physio bed.”

How are they done, these sheer feats?

“I don’t know if I can explain,” Robbie reflects.

Horses of great distinction sprinkle lustre on all connected. For the jockey, making the grade requires Grade 1 wins. But there are hidden levels of achievement.

“If you get a horse that’s not a good jumper to jump well and win, that gives you the most satisfaction,” Robbie divulges. “I’d rather go out on a horse that is not the best jumper in the world but is a 6/4 shot than go out on a horse that is a brilliant jumper but is a 66/1 shot.”

He runs through the calculations: “Even cantering to the start, you’d have a fair idea of the horse’s limitations. Maybe he’s not that scopey. So you have to get in short at every fence. Maybe, when he gets in short, he’s not able to use himself. So you have to keep him off his fences. After jumping one or two fences, you’d quickly get to know what his capabilities are and then it’s having the nerve not to ask him outside his capabilities.”

Con uncovers the kernel: “That’s horsemanship.”

***

Prized photographs adorn the walls of Robbie Power’s home. Cheltenham or Aintree, Punchestown or Fairyhouse, each track a mount for this winning rider. The big days of his career are captured in colour: Our Duke and 2017’s Irish Grand National, Jury Duty and last year’s American National, Sizing John and that Gold Cup. Silver Birch meets you coming in the front door, leaping above the piano, the Grand National in sight.

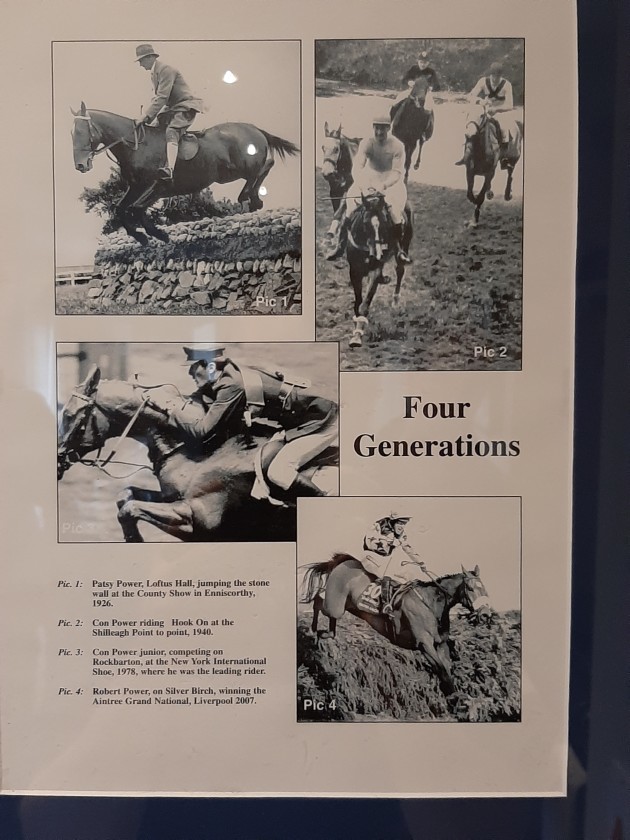

One fitting looms in black and white, hanging just inside the kitchen, demanding closer inspection. This frame holds four images and Con takes evident pride in the role of curator. His grandfather Patsy appears at the top. His father, also Con, sits underneath, riding at a Point to Point in Shillelagh. Then himself, the dashing Captain, competing at the New York International Show. Robbie, clearing the last at Aintree, completes a collection entitled ‘Four Generations’.

“I’m very proud of that,” Con remarks. “There’s not that many houses you walk into where you see them in competition.”

Then the clock turns back as he contemplates that part of his life captured on the wall: “I was leading rider that year. My picture appeared in The New York Times. I won a whole pile of classes. They made a big thing of the presentation at the show. 27,000 people packed into Madison Square Garden. The whole job.”

Suddenly a pause. He walks across the kitchen and says nothing until he finds an appropriate prop for the punchline. From the kitchen sink, he plucks a baby’s beaker.

His recollection resumes with an affronted look: “The trophy? That size, with ‘Leading Rider’ engraved on it. End. Of. Story. When they came out with that, I thought: ‘For the love of Jaysus.’ I thought I was going to get some gold watch.”

I have nothing more valuable to offer when I ask him to stand in for a picture.

“I charge for photographs,” he ribs.

“Send me on an invoice,” I counter.

My riposte meets with his approval: “Well answered, well answered. Good man, good man.”

With that, he stands in for the shot.

“Am I tidy?” he asks his son.

“No,” comes the firm response.

“Will I take the jacket off?”

“That’s not going to make you tidier. Zip it up. Zip up the jacket.”

Job done, he faces forward, smiling now appearance has improved.

Before we finish, the Captain delivers another declaration of the family creed: “We leave Derrypatrick to go to win. I know what winning means to myself and to them.”

Robbie remembers the summer past: “My sister [Elizabeth] won an international class at Dublin this year and he said it was the best day of his life.”

“It was a bit special,” Con allows. “For my daughter to win an international class at the Dublin Horse Show, with the best riders in the world competing against her, that’s a bit special. That will live with me forever.”

Watching that sequence unfold revived his sharpest memory: “Once that gate closes in Dublin, that’s it. I can still hear the click. Gate number 64. You’d trot through the gate and you’d hear the gate clicking behind you: ‘This is fucken it now.’ You’re on your own then.”

Robbie signs off: “You’re on your own then.”