WHEN I BECAME a parent for the first time in 2013, a lot of questions went through my mind.

Will I be a good dad? What am I supposed to do with this tiny human that is now completely dependent on me? Will I ever get any sleep ever again?

One question I never thought of was how having a son born in October would affect his chances of playing schoolboy football. But it does, and massively so.

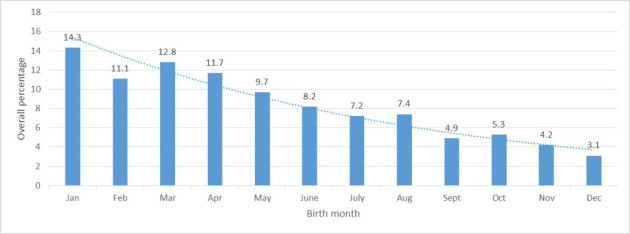

Indeed, in the Dublin District Schoolboy League (DDSL), 43.8% of all players over a six-year period were born in January, February or March.

By stark contrast, less than 10% were born in the final three months of the year.

Those are just some of Waterford IT lecturer Laura Finnegan’s findings regarding a phenomenon called the ‘Relative Age Effect’ (RAE) which she has recently published in a paper called “The influence of date and place of birth on youth player selection to a National Football Association elite development programme”in the Science and Medicine in Football journal.

[You can read an overview of the study here]

The paper is part of Finnegan’s Phd studies and was prompted by Ireland’s dire performances at Euro 2012.

“My day job is as a lecturer in Waterford IT and I work on the recreation and sport management and sports performance programs down there,” Finnegan told The42 recently.

“The idea of doing a PHD was always on the radar but I was just waiting for something to really catch my attention, particularly doing it part-time with a full-time job.

“For myself, it had to be something I was going to be really passionate about.

So where it came from was sitting over in Poznan five years ago and, like an awful lot of people, I could continue to be a passive fan or I could come home and try to make a difference in some small little way.

“I sought a research team. I was keen to go outside of Ireland, you know yourself, schoolboy football can be tied up in all sorts of politics and emotion. Therefore, ideas that are really progressive and forward-thinking sometimes fall at the first hurdle because of the underlying bias people have.

“So I went outside the country and I came across David Richardson and Martin Littlewood in Liverpool’s John Moore’s University. They’d been involved in shaping the processes for a number of FAs around Europe and I was keen to tie-in with them.

“The two lads, myself and Jean McArdle from WIT sat down and made a plan for where the study was going to go. I think it just gives it a fresh look, bringing two international experts on board who had no biases or insight into anything that’s happened here before.

“I think that makes you assess everything with a bit more of a critical eye when you have to explain everything from scratch.”

Perhaps one of the most surprising findings of Finnegan’s study was that the actual birth rate of boys (blue below) is almost evenly spread over the entire year:

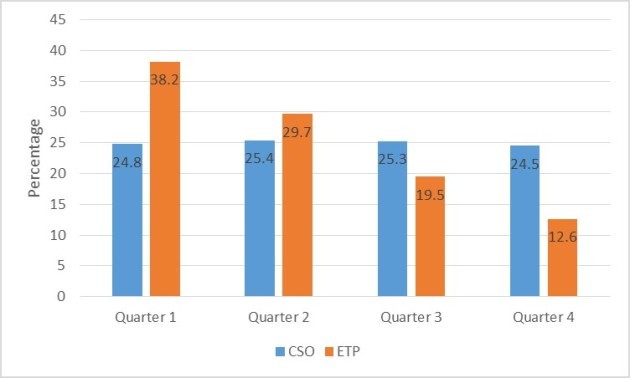

The orange bar in the graph represents players taking part in the FAI’s national Emerging Talent Programme (ETP).

And even though it’s not as stark as the DDSL age range, it’s still quite skewed towards players born early in the year.

“Ideally you’d compare those in the ETP to the overall playing population but those stats don’t actually exist for a variety of reasons.

“Plan B was to compare it to the overall population of boys and I did a bit of work with the CSO on that and what we found was that, of all the boys, through all the years, the birth rate was roughly 25% per quarter which is fascinating in its own right.

“But there’s no doubt, if you look at the really sensitive years, like the early teen years, the date of birth has a massive impact on team selection.

You literally have the potential for a boy to be a full year older than another kid he is playing with or against and, depending on which side of midnight he was born on 1 January, he could be the biggest kid on his team or the smallest.

“It’s probably important to note that it’s not just the physical advantages some kids have. It’s also to do with cognitive and emotional development. Even just social skills. That side of things is fascinating as well and has a lot of grounding in educational literature.

“It does level out a later ages but, if you look at different structures – the ages leading up to the Kennedy Cup for example — all through that early adolescent age, size and maturity play such a key role.”

Finnegan admits there’s a danger that, seeing graphs above which shows that boys born in January are four times as likely to earn a spot on the ETP than those born in December, parents won’t send their kids to training because they don’t think they stand a chance of getting a game.

This is short-sighted as players born later in the year are actually over-represented at the professional level.

“I suppose it is a fascinating study but the danger is that it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Sometimes the danger of getting these things out there is that people kind of think that ‘oh no, my child was born in October and now there’s nothing I can do’.

“But, it’s all about awareness and this was the first study of its kind to look at the schoolboy age. Others have looked at U21 and senior international set-ups but there were over 2000 boys in this study and it was completed over six years.

“For parents, they often become coaches so they’re linked to the situation sometimes and there’s a really interesting flip in football later on because, if you can keep them in the sport and keep them enjoying it, the ones born later in the year are over-represented at professional level but that’s a whole other conversation.”

Even with a bias towards bigger kids, the fact enough of those born later in the year stick with the sport means Finnegan believes it’s unlikely an Irish Messi will ever slip through the cracks based on his size.

But what can be done to keep undersized kids who aren’t destined to be superstars playing football? The answer, as it usually does, comes down to resources.

We need to educate coaches on their bias, even when it’s subconscious, and encouraging even more parents to get involved in coaching would help with keeping their kids playing.

“The FAI, to be fair to them, are well aware of the issue and Niall Harrison has done great work in that regard, educating coaches on spotting players who may be ‘late bloomers’ and the like.

“The simplest solution may be to change to rotating cut off dates for younger age groups, or even move to an a/b calendar year — with January and July as the starting points — giving more scope for players of all sizes to stay involved in schoolboy football.”

For more information on Finnegan’s study, click here.

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!