ON THE NIGHT of 11 February, 1990, Seamus McDonagh was with his girlfriend and her family at their apartment in Staten Island.

They had gathered to watch what was supposed to be another routine title defence for Mike Tyson, the undefeated heavyweight champion of the world, who was expected to encounter little difficulty in clocking up his 38th professional victory.

The 10th-round KO win for Buster Douglas in Tokyo shook up the world of boxing, but McDonagh hadn’t considered that there might be consequences for his own career. The subsequent offer of a fight against Evander Holyfield therefore took him by surprise.

Tyson’s bout against Douglas had been viewed as no more than a tune-up fight for ‘Iron Mike’ ahead of an eagerly-anticipated clash with Holyfield, who was waiting patiently for a heavyweight title shot having moved up after conquering at cruiserweight.

But Douglas wasn’t ready to defend his newly-acquired title until the following October, at which point Holyfield would have spent 11 months out of the ring. Holyfield’s desire to stay active in the meantime led him to Seamus McDonagh.

“Initially I didn’t want the fight at all,” McDonagh admits. “Holyfield was the best heavyweight in the world. Why the hell would I want to fight him?”

McDonagh had fought most of his professional career at cruiserweight and was once ranked third in the world in that division. A few wins in the higher weight-class in 1989 pushed him into the heavyweight rankings – and into the path of the next world champion.

“We declined the fight at first,” he continues. “Then they told me I’d get $25 million and a shot at the heavyweight title for my next fight if I won. That suddenly made it sound a lot more attractive.”

McDonagh’s boxing education began in the gym behind Gorry’s petrol station in Enfield, Co Meath, when he was a kid. His father, Jim, had fought as a professional before coaching Seamus to win Irish junior titles.

The sporting lineage runs deep in the McDonagh clan. Seamus says his brother John, who won the Golden Gloves in Chicago, was the better boxer of the two. Dalton — John’s son and Seamus’ nephew and godson – is a current member of the Meath senior football panel. Their cousin, also Seamus McDonagh, is the goalkeeping coach on Martin O’Neill’s Republic of Ireland backroom staff.

Seamus relocated to Brooklyn in 1982 as he was entering his 20s. He had often been a reluctant boxer but the sport travelled with him across the Atlantic nevertheless. At the third time of asking, he won the Golden Gloves in New York in ’85 – “five fights, five knockouts and Muhammad Ali presented me with the Golden Gloves afterwards” — and it proved to be a significant turning point.

“I basically went from obscurity to being this white heavyweight boxing star around New York,” McDonagh explains. “That ultimately changed my whole life.”

McDonagh had just completed his first semester as an English literature student at St John’s University but was struggling to find the money for the next phase of the course. After his Golden Gloves success, boxing provided the solution.

“When I won the Golden Gloves, all these offers to turn pro started coming in. I didn’t have any money to pay for my second semester at St John’s. I decided to turn pro purely so I could pay for college.”

The $2,500 signing fee enabled McDonagh to continue learning about Kipling, Faulkner and Hemingway while he embarked on a career in professional boxing. The early years were promising too.

By the end of 1989, McDonagh had lost just once in 21 bouts. Along the way he fought at Madison Square Garden and on the undercard of Barry McGuigan’s successful WBA featherweight title defence against Danilo Cabrera at the RDS. But the biggest occasion came in June 1990.

At a press conference ahead of his meeting with Holyfield in Atlantic City, McDonagh acknowledged his status as a sizeable underdog – Las Vegas oddsmakers declined to offer a betting line on the fight – but he used Tyson’s defeat to Douglas as evidence that anything can happen between the ropes on fight night.

“The situation is perfect for me,” McDonagh told reporters. “I may not be up to it, but look at my opportunity. As a people, the Irish are considered good battlers. We’re right there to the very end. My father was a fighter. He’s here and he’s loving this.

“I have never been down on the canvas as a pro. I have more power than Holyfield’s last two opponents [Alex Stewart and Adilson Rodrigues] and I have speed. What Buster Douglas did to Mike Tyson excites me and gives me confidence. I think I can do it here.”

McDonagh had emigrated eight years before he took on Holyfield so the fight didn’t cause much of a stir back home, where the country was in the midst of Italia ’90 fever with just over a week to go until Ireland’s debut at the World Cup. But there was plenty of interest from the media in the US.

“Generally speaking, Irishmen love to tell stories,” wrote Phil Jackman in the Baltimore Sun. “And given a few more years, Seamus McDonagh might be a match for any of the fabled raconteurs of the Emerald Isle.

“Few are giving the willing but untested McDonagh much chance against unbeaten Evander Holyfield, who is marking time while waiting for an expected heavyweight title shot against Buster Douglas this fall.

“Mr McDonagh is hardly your run-of-the-mill challenger, a breed that always seems to disintegrate when thrust into the limelight. Form says there’s no way it can happen, but Seamus McDonagh is a long shot it’s fun believing in.”

When Holyfield was asked at the pre-fight press conference about a recent cameo role in a film, McDonagh interjected with his own tale of a dalliance with the movie industry.

“I was in a picture too — although inadvertently,” he said. “They were filming one day on Fifth Avenue in New York and I nearly ran over Paul Newman.”

McDonagh was referring to his job driving a horse and carriage around Central Park and Manhattan, which funded his early years in New York. He’d eventually have a more substantial CV when it came to acting.

The limelight that accompanied the build-up to the fight was something McDonagh enjoyed, but he admits that sharing the ring with Holyfield was a “terrifying” experience at first. An impressive physical specimen who possessed a significant size advantage, Holyfield was undefeated at 23-0 having turned professional after winning an Olympic bronze medal in 1984 at the age of 21.

“Initially it was daunting,” McDonagh says. “Very daunting. As soon as the bell went in the first round, the fear hit me. One of the regrets I have about the whole thing is that I remember seeing my dad trying to get past my management before the fight so he could come and have a word with me. He used to do that before every fight and it always made me feel more relaxed.

“But for some reason I kind of feel like I abandoned him because I didn’t insist that he get to talk to me. I don’t know if it would have made a difference to the fight but it definitely would have had me calmer in the first round.

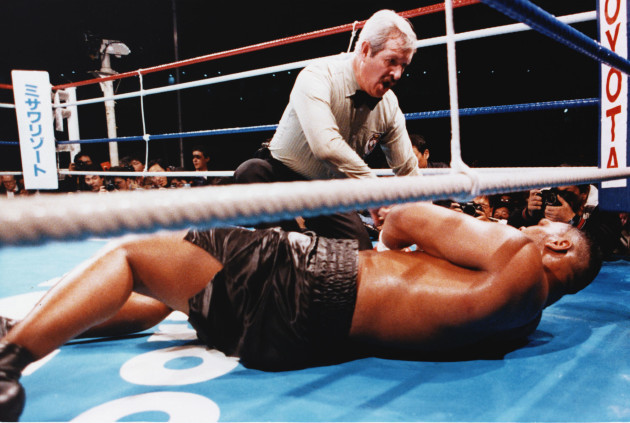

“Overall I’d say that the fight was a traumatic event. The fear was there at the start and Holyfield got a couple of flash knockdowns in the first round, but I was fine. I was up straight away each time. I got over the fear gradually. In the second round I did a lot better and I did great actually in the third round.”

Inside the first minute of the fourth, however, the fight was over. Holyfield planted a powerful left hook on McDonagh’s chin and the English literature major from Meath went down. He wasn’t counted out and insisted he was capable of continuing, but referee Joe Cortez saw things differently.

“Holyfield methodically took apart the challenger,” was Phil Berger’s assessment for the New York Times. “But McDonagh tried. Only a few of his shots landed, but he was clearly determined to make a fight out of it against Holyfield.

“McDonagh came charging forward, throwing left hooks just seconds into the fight — wide-arcing, wind-making blows launched with an underdog’s earnest hope of getting lucky early.

“But luck, it turned out, was no substitute for a world-class punch. Holyfield had that punch: a fourth-round left hook that thudded against McDonagh’s chin, sending the 27-year-old onto the canvas and preserving Holyfield’s anticipated shot at the world heavyweight champion, James ‘Buster’ Douglas.”

In his changing room after the fight at the Trump Plaza, McDonagh received a visit from the proprietor. Businessman in 1990, US president-elect in 2016.

“Donald Trump came in and said, ‘You put up a great fight, I want you to contact me so we can work together’, all this stuff. But I never did. He had come all the way across the casino to say ‘hello’ to me.”

McDonagh fought just once more following his defeat to Holyfield. After losing to the man who became heavyweight champion of the world four months later, McDonagh began working with Joe Fariello, who he describes as his first “world class” boxing trainer. Fariello had been a prodigy of Cus D’Amato – Mike Tyson’s legendary coach – in Catskill.

“Looking back, I was 27 before I really learned how to box,” McDonagh explains. “But with Joe Fariello, I had a big argument about over-training for my next fight. He said there was no such thing as over-training and Cus D’Amato agreed with him. But that amount of training and sparring did me more harm than good.”

In June 1991, McDonagh lost by TKO in the seventh round in a cruiserweight bout against Jesse Shelby. A headbutt in the second round has left his memories of the fight faint. What he does recall is that he was in a bad place afterwards.

Weak and exhausted from the excessive training, he was emphatically defeated — “the only beating I ever really took” — by an opponent he was expected to overcome. McDonagh didn’t want to fight again after that and he never did.

“I took a lot of punishment in that fight. I was worried about brain damage and I slipped into a depression,” says McDonagh, who admits that he battled his demons throughout his 20s and consequently made an attempt at taking his own life.

The Holyfield fight didn’t bring him $25m but McDonagh was booked for $120,000 instead, which made it comfortably the most lucrative bout of his career. But after the deduction of taxes and training fees, and when you’re a young man in New York who’s fond of a drink, it doesn’t take very long to part with that kind of money.

Having fought his last fight, McDonagh jokes now that boxing no longer got in the way of his career as a drinker. But it wasn’t a situation he could afford to laugh about at the time.

“I always trained very hard as a professional athlete,” he explains. “I would stop drinking about a month before a fight but go back on it straight afterwards. I often felt suicidal then. A few years earlier I took a bunch of pills but nothing really happened. When I stopped boxing, the only thing that probably kept me alive was the thought that I could drink as much as I wanted to because I didn’t have to train for fights anymore.”

McDonagh needed to make a change while he still could. His penchant for the public houses of Manhattan eventually necessitated a move away from New York and across the country to San Francisco, where he still resides now in an apartment a few blocks off Union Square.

“There’s a song [‘Viva La Vida’ by Coldplay] that mentions sweeping the streets that you used to own,” McDonagh explains. “That’s how I started to feel about New York. Everywhere I turned there was a bad memory. I frequented every bar in New York and my identity was attached to being this celebrity boxer. But the reality was that I was feeling suicidal.”

The drink didn’t follow McDonagh to the west coast, but acting did. Shortly after he decided to retire from boxing, McDonagh met Dublin actor Jimmy Smallhorne – who in recent years played ‘Git’ in Love/Hate – in Manhattan. Smallhorne helped McDonagh to secure a part in a play about Bobby Sands at New York’s Irish Arts Centre. He’s been involved in the industry ever since.

McDonagh: “My first role was actually when I was on the St John’s campus one day and I saw an advertisement for a production of the ‘Guys and Dolls’ musical. I thought it sounded like fun so I auditioned and they gave me the part of the Irish cop, Lieutenant Brannigan. I only had a couple of lines but I loved it.”

While playing the lead role in a Broadway production which tells the story of former boxer Bobby Cassidy, McDonagh opened the door for a friend to make the same transition from boxing to acting. Retired Derry middleweight John Duddy joined the ‘Kid Shamrock’ cast in 2011.

McDonagh hopes to begin production soon on ‘The Last Sparring Partner’, a short film he has co-written, and in February he’ll mark 21 years sober. But he’s keen to ensure that there’s no sugar-coating involved in any portrayal of his life.

Acting and film-making is a labour of love and it’s going well, but it’s not a full-time gig. He pays the bills via other means. Largely due to the effects of his career as a boxer, McDonagh juggles several different roles.

“Right now, the biggest part of my life is that I’m sober and assisting other alcoholics to stay sober,” he says. “That’s what I get most satisfaction from. But the fact is that I came out of boxing with no money. I can’t work a full-time job because my brain is too damaged to concentrate for more than a couple of hours at a time.

“I work a few different part-time jobs: shoe shine, taxi service, a meal delivery thing – but like most fighters, I will be paying dearly for the rest of my life for my brief glory days in the ring. I have a hard time learning anything new.”

That’s a message he intends to convey in his forthcoming short film. ‘The Last Sparring Partner’ will highlight the level of brain damage sustained by boxers. It’s an issue that’s close to McDonagh’s heart, yet it still doesn’t prevent him from occasionally wondering what might have been had he not ended his career in the ring at the age of 28.

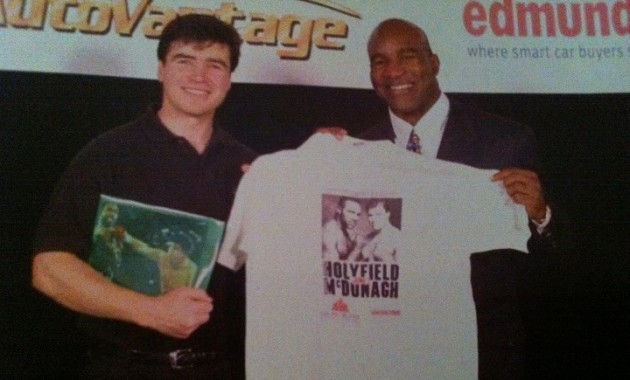

“I’ve met Evander [Holyfield] a few times since we fought,” McDonagh says. “He has been friendly to me mostly. Very respectful and very kind, a good guy. I don’t know whether he got jealous or what but when I was in ‘Kid Shamrock’, the night we were opening on Broadway he came out in an interview – completely out of the blue — and accused me of using steroids. Me, of all people!

“This was about seven years ago. Maybe he wanted to get something going again for a comeback because he said he’d fight me for half a million dollars. It’s funny because even still to this day I think I could get in there and do it again.

“The man might leave the boxing ring but the boxing ring never leaves the man.”