JOHN WHOOLEY STOOD at the water’s edge, where the land gave way to another world, a utopian existence where it was simply rower, boat and river. He had stood here before, thousands of times, and always followed the same ritual.

He looked to the sky, where, in this case, the clouds sat sullen. There was a faint outline of the sun behind them, a lowering grey shadow waiting for its chance to shine. The seagulls were in, which meant it must be rough to his left, the west, where the Ilen River introduced itself to the Atlantic Ocean.

The Ilen is the playground for Skibbereen Rowing Club, its boathouse and clubhouse sitting behind John on the riverbank. Just metres separate these structures from the river.

The Ilen had been home to fishermen for generations before the rowing club was formed in 1970, but as the fishing died away it was the rowers who reinvented the Ilen. They have it to themselves now, a 10-kilometre stretch from the clubhouse without having to stop. It’s the envy of every other rowing club in the country. Every year 7,000 boats are launched by the club onto the river.

John had it almost to himself on this October evening in 2007. There were four young bucks, early teens, getting ready to go out in a quad scull. They were busy doing their own thing.

The Ilen was in a good mood – not too choppy, not lazy either, but quite eager. The water rushed excitedly against his wellies, waiting to play. Its best time is an hour before high tide; that’s when it’s at its calmest as there’s less current and flow on it.

The wind was in impish form too. It blew from the south-west, racing in off the Atlantic. On its worst days it bullied rowers, daring them to take it on. However, the rowers never shirk a challenge. The wind was simply another competitor to beat and it could be like this on race day. Saying that, when it’s in a real mood, they know better. It’s not worth the hassle on those days. But this evening, with the nights shortening and the temperature dropping, it was calm.

John knew the signs were good. Most of the time he rowed downriver towards Baltimore, going with the current. Other days, depending on the strength of the wind and its direction, the height of the waves, the tide, the weather and the sunlight, he would row upriver, towards Skibbereen town, for its calm and sheltered water. On those other days, when the weather gods played spoilsport, he would stay on land and take out his frustrations on the rowing machine. This evening, though, he would point his boat west.

He headed out on the water in his single scull, a boat designed for one person. This was his familiar Filippi, white with its distinctive blue stripe, which he had bought two years earlier for just under €5,000. It was good value. John and two other Skibb rowers, Richard Coakley and Kenneth McCarthy, bought one boat each in a package deal that Richard organised after competing internationally. This was the first single John had owned. His pride and joy.

A heron across the water stared straight at him, waiting to see what John did next. The bleating of the sheep in Carey’s farm on the far side of the river didn’t stir the heron. Neither did the odd car passing on the road behind it. Instead the heron eyeballed John. It wasn’t keen on sharing the Ilen today. But it knew the signs, so it ultimately spread its wings and moved on.

John had been looking forward to getting back out on the water. By day he worked locally at O’Donovan’s boatyard whenever they needed him – the recession had cost him his job as a CAD & Design Technician in Galway in early 2007 – and in years to come he’d retrain to be a maths and physical education teacher, but on the Ilen he was a rower.

Even better, a Skibbereen rower.

That’s a badge of honour. It means something.

He lived on the opposite side of town, a short drive from the clubhouse, but for these next 80 minutes he would be in a different world. He quickly ran through his checklist: hat, leggings, enough layers of clothes to stay warm, shades, water bottle. He was good to go.

His bare hands felt the slightest chill in the air. It wouldn’t be long before the fading sun set behind Mount Gabriel in the distance and took a large splash of what little heat there was with it. His right hand gripped both oars, locked into their gates, to keep him balanced as he set about launching his boat on the river. He sat on the sliding seat. His left hand steadied the boat. One leg in, the other out, coiled to push the boat away from the slipway. He was almost free from the land. He used his right oar, as well as his free leg, to gently push his boat into the water. It looked easy now, but had taken plenty of practice in the early days.

Soon he was in deep enough. He was free. It was just him, his boat and the water. Wellies off. Feet into their straps. All set. A quick look backwards opened up a view of the Ilen that stretched for 800 metres. There was no one else there. He was pointed in the right direction and he had it to himself – for now, at least.

The rowers’ code says that your right blade should always be closest to the bank. That’s the simple rule to remember. A handwritten sign on a door in the clubhouse carries other rules:

- You must have lights at all times on your boat.

- Do not launch without lights.

- Always paddle in groups and not alone.

- Down – clubhouse side. Back – Schull road side.

- Always stay off the centre of the river.

John was experienced enough to go alone. Soon, he was warmed up, the half slide of his seat gone to full slide as his hands felt the oars connect with the Ilen. He pulled in, down and away, and slid his seat under him to take another stroke. In. Down. Away. Reach. Slide.

This was repeated, stroke after stroke after stroke. It’s a delicate balance of power and speed. He was in rhythm and conducting his own one-man orchestra. He would take over 1,600 strokes during this training piece. Practice makes perfect in rowing. It’s all about mileage and building endurance.

He was in the zone now, fully concentrating. The boat glided along the water. From a distance, rowing looks deceptively effortless and elegantly beautiful, but life in the boat is different. It hurts and burns and hurts some more, pushing the body and mind to their limits. It’s a life choice. You commit or you don’t. John had committed long ago.

He manoeuvred through the dogleg corners of Newcourt and Oldcourt. The boatyards in Oldcourt were crowded with summer sailing boats, resting for the winter, their masts clanking in the wind.

He saw them first, in the distance. It was that Junior quad. Then he heard them, whooping and hollering, like Indians in a Western film. He was their cowboy. He shook his head. It was Gary, Paul, Shane and Diarmuid, four little terrors that were causing wreck on the river. He knew them all.

They were four different bundles of energy, each more wired than the next, some cheeky, others quiet. But none of them ever rested. They were in secondary school now, in St Fachtna’s de la Salle in town. Paul was 13, the youngest. The other three were 14-years-old and they were already fearless on the water.

John knew they wanted a race. That’s what they did. It was time to teach these pups a lesson, again.

John was 28 and one of the club’s most experienced oarsmen, part of the Senior-level clan, along with Olympians Eugene Coakley and Timmy Harnedy, Richard Coakley (who was an Olympian in the making) and Kenneth McCarthy. Every weekend, when they were out in their singles, this Junior quad turned up and tried to beat them all. They trained all week for the weekend.

‘Old man John,’ broke the silence, carrying over the water. It was Gary.

It was time to race, to put them back in their box. All Skibbereen rowers are taught to race. Whether it’s a training piece on the Ilen or an Olympic final, they all approach it in the same manner: first home, first past the finish line. First, first, first.

Concentration was key. He drove his legs down faster, keeping his balance, not letting his oars hit the water. One of the earliest lessons taught to him was that friction is wasted energy and leads to a slower boat. Those words came from Dominic Casey, who taught him everything he knew.

It was also Dominic who saw a rower in John when no one else did. This tall, gangly teenager was a late starter in rowing, almost 17-years-old when he was cajoled into a sport that he had no interest in whatsoever. But Dominic spotted that there was raw material to work with.

‘One stroke at a time,’ he told John, over and over again.

Always one stroke at a time. Stay in the present, John. If you pull a bad stroke, make sure the next one is better.

‘You can’t control what has happened but what you can control is what you do right now,’ Dominic advised.

John took it one stroke at a time from the very start. And he got better and better. Faster than anyone could have ever imagined, apart from Dominic. His progress was startling.

But so too was that of the Junior quad, who at the time were coached by Gary and Paul’s father, Teddy O’Donovan.

‘Go get those old fellas,’ he would tell the four boys, as they almost climbed over each other trying to get into the boat. ‘Show them no respect.’

John had his game face on. This could be a race day. The quad was a good distance away still. He just wanted to make one burst, one lunatic minute. He made his move, pushing his burning legs, straining his body. It was the same stroke he had used to win his first National Championship title in the men’s Novice coxed four in 1996, less than 12 months after he first picked up an oar. The same stroke that took him to the 1997 World Junior Rowing Championships in Belgium, where he represented Ireland in the Junior men’s quad less than two years after he started rowing.

The very same stroke earned him a scholarship to the University of California in Berkeley and saw him excel there. That stroke saw John finish fifth in the world in the single at the Under-23 World Rowing Championships in 2000. That stroke served him well.

After his manic minute, he could tell that they were not gaining. Point proven, for now. He moved down from top gear and the prize was a few moments taking in his surrounds. Creagh, Inishbeg, forgotten churches and old landlord houses, a glimpse into Ireland’s past. This is a stunning backdrop for the rowers, a river with a variety of currents that prepare them for all conditions at regattas. It’s a setting straight from a novel.

The river smelled different to John at this point, the earthy smell now salty. The Atlantic was closer. He heard it in the distance. The water looked and felt different. He was near the end of the river now, not too far from Sherkin Island, so it was time to turn around and head for home.

John took his time and let the quad catch up.

‘Take it easy, lads,’ he snapped, ‘it’s getting dark so quit the messing.’

They took absolutely no notice. Diarmuid just laughed.

‘We’ll race you back.’

He let them off, as the boats turned for home.

Soon, heading back up the river, he caught a glimpse of Dominic’s house to his right. He was only in there a couple of years at this stage, but this beautiful, stone-clad, two-storey building perched on a hill in Ardralla that overlooked the Ilen from the northside was already the watchtower that cast its eye over the river. It has a magnificent view from Dominic’s open-plan kitchen, sitting room and the glass-windowed conservatory that wraps around the far end of the house.

They are all vantage points offering a different angle, upriver towards O’Donovan’s boatyard at Oldcourt where he worked, downriver towards Inishbeg, an island, and directly across the river, where Lough Hyne hill rises in the distance.

If a boat moves on the Ilen, Dominic knows who is in it, what they are doing and how well they are doing it.

He has binoculars upstairs and downstairs. And a megaphone too – his trusty messenger that has gotten wet more times than some boats. If he spots a boat on the wrong side of the river, they will hear about it. Or if he has advice, he will offer it too. He never switches off. Ever.

He either stands on the picnic bench outside the front of the house or appears out through a gap in their hedge. Dominic, his megaphone and his words of wisdom.

There were plans to trim the hedge at one point but his wife, Eleanor, prefers nature’s own look, no straight lines, so Dominic let it grow. It was over six-foot high now, as John passed it, the perfect camouflage to hide Dominic until rowers heard his voice bounce across the river.

Luck would have it, too, that his home is in line with ‘the first slip’, that is the starting point for Skibbereen rowers’ ‘pieces’, which are training races. From this point the river runs straight for almost three kilometres down to Inishbeg.

But this evening there was no megaphone. There were lights on in the house, but there was no Dominic to be seen or heard. That meant he was at the clubhouse, making sure every boat that went out had come back in.

The wind was at John’s stern now. This spin home would be faster, as he was on a speed-assisted tide. Daylight slowly fading, he rowed hard but steady, wanting to make sure that his time back to the clubhouse was minutes faster than the first half of the training spin. Stroke after stroke after stroke repeated. Before he knew it, and with a quick glance behind, he caught sight of the distant lights of the clubhouse as he rounded Newcourt corner.

The Junior quad had already pulled in. Good, they’re home, he thought. Not long for him to go now. A look at his watch showed his time was quick as he eased his way into the slip. Good job. Good row.

Gary, Paul, Diarmuid and Shane were cleaning the quad. Dominic was there, all right, checking in. So was Teddy, their coach, who sensed something about his two boys. They were catching up with the Seniors all the time. And they were always hungry for their next feed of rowing.

Finished, John lifted his boat out of the water and around to the side of the boathouse. Then he rested it upside down on waiting stands, washed it with soapy water and rinsed it off with the hose until it was sparkling again. Next he carried it over his head into the boathouse and perched it in its familiar spot, inside the door to his left, on the rack closest to the water. This is where the Senior rowers keep their boats, closest to the doors. Junior rowers’ boats go to the back of the boathouse. You earn your spurs here, and the little perks that come with it.

‘We got you this evening, John; we were in first,’ Gary laughed, those wild eyes darting in John’s direction.

He smiled back. Tomorrow was another day.

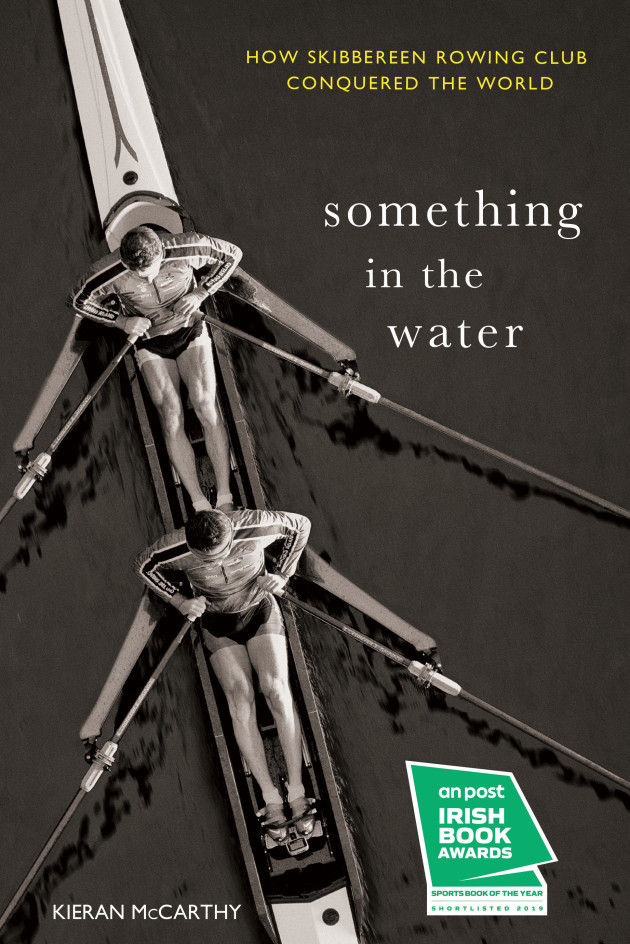

Something In The Water is published by Mercier Press and available in bookstores now.