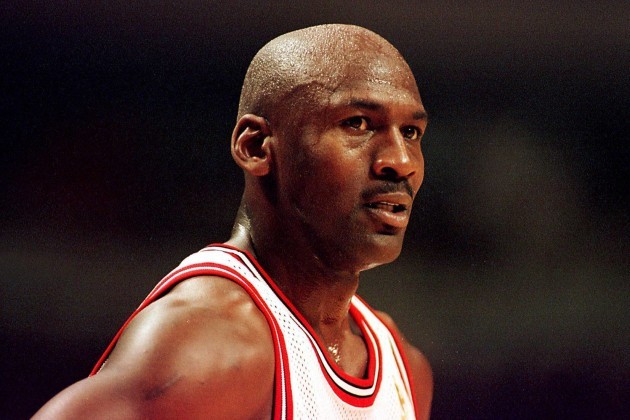

SOME OF THE most fascinating scenes in ‘The Last Dance’ documentary are the seemingly mundane moments where Michael Jordan is interacting with his fellow players and Chicago Bulls staff in the locker room.

The footage of Jordan berating team-mates on the court during practice games, pitching quarters with his bodyguards make for gripping viewing as they lift the curtain on the inner sanctum of one of the greatest sports teams of all-time.

One surreal moment takes place during the ’98 playoffs when Jordan is sat at his locker, decked out in Bulls training gear with a cigar in his mouth and a baseball bat in hand, while he sounds off about Charlotte Hornets guard BJ Armstrong.

“Let’s see if all that trash talking starts when it’s zero-zero instead of a five, six point lead,” says Jordan as he half-swings the bat, “When you’re ahead it’s easy to talk.”

Jordan looks more like a character from a 1940s mobster movie than NBA superstar.

It gave an insight into Jordan’s mindset and his maniacal competitiveness, even at 35 and in the twlight of his career.

Jordan played his last game for the Bulls weeks later in June 1998, but didn’t announce his second retirement until January ’99. An NBA lockout saw games between October and January cancelled due to a dispute about league’s salary cap system between players and owners.

In the summer of ’98, Jordan severed a tendon in his right index finger while using a cigar cutter that would have sidelined him for a lengthy period anyway. With no guarantee there would be a 1998/99 season, plus Phil Jackson’s departure in Chicago, he decided to call it quits.

By the time a truncated 50-game season started in February ’99, Jordan had sailed into the sunset.

Though he would later return as a 38-year-old for a two-year stint with the Washington Wizards, his second retirement marked the end of the Michael Jordan.

In the doomsday scenario that no inter-county championships take place in 2020, it’s worth speculating whether – due to the Covid-19 pandemic – we’ve already seen the last of Stephen Cluxton.

He spent the first half of this year rehabbing after shoulder surgery. He considered his future before committing to Dessie Farrell’s set-up for 2020.

He’ll be 39 by the time 2021 rolls around and only Cluxton can answer whether he has the hunger to go again next year.

The nearest we’ll probably ever get to a behind-the-scenes look at Cluxton in the dressing room was in the documentary ‘The Dubs: The Story of a Season’ which chronicled their 2005 championship campaign under Pillar Caffrey.

Notoriously reticient to conducting any media duties in the past 15 years, he spoke openly during the documentary about his approach to training.

A week before they played Wexford in the Leinster semi-final, he was sidelined with an ankle injury and opened the curtain on how much he hated missing training.

“I actually wasn’t able to train,” Cluxton said. “I needed to practice kickouts because I wasn’t doing well. I needed to go out and practice goalkeeping, my handling and keeping myself fresh.

“Because if I didn’t it would really, really frustrate me. It gets to my head if I can’t train.”

It’s a topic he revisited last November in a rare interview after being named Footballer of the Year. The Parnells stopper revealed the self-doubt that creeps up on him when he can’t train to the required level.

“When I got the injuries then it just curtailed all the training. it leads to doubts in my mind then as to my ability at the standard that I want to be at and whether or not it will cost the team in the end.”

He suffered three broken bones in his back, a punctured lung and cartilage damage to his shoulder in 2018, yet missed just one game. Surgery on his shoulder followed over the past winter, which ruled Cluxton out for the 2020 league.

“I still have dodgy ankles from a long time ago,” he added. “So it was a struggle to try to get back up to the level I wanted.”

Cluxton and Jordan are from two different sports and eras, but they share that insatiable hunger that all the great athletes have. They set the standards for others to follow. Jordan’s intensity in practice was legendary. In his eyes, he was preparing his team-mates for playoff basketball.

“Winning has a price,” said an emotional Jordan at the end of Episode 7. “And leadership has a price. So I pulled people along when they didn’t want to be pulled. I challenged people when they don’t want to be challenged. And I earned that right because my teammates came after me. They didn’t endure all the things that I endured.”

When Jordan was drafted to the NBA in 1984, the Bulls were depicted in the media as a ‘travelling cocaine circus’, an accusation he didn’t deny in the documentary. It took them seven years to go from a laughing stock to NBA champions.

Along the way, Jordan learned what it took to win. Certain standards had to be maintained – and not just on gameday.

“Once you join the team you live at a certain standard that I play the game, and I wasn’t going to take anything less. Now, if that means I have to go in there and get in your face a little bit, then I did that.

“You ask all my teammates, the one thing about Michael Jordan was he never asked me to do something that he didn’t fuckin’ do.

“When people see this they’re going to say, ‘Well he wasn’t really a nice guy. He may have been a tyrant. Oh-oh.’ Well that’s you, because you never won anything. I wanted to win, but I wanted them to win and be a part of that, as well.

“I’m only doing it because it is who I am. That’s how I play the game. That was my mentality. If you don’t want to play that way, don’t play that way.”

You suspect Cluxton subscribes to a very similar code.

The stories of him showing up to training two hours early to practice his kick-outs are legendary. Former Dublin number two John Leonard recalled in his autobiography how he would try to beat Cluxton to training to get an edge on him, but couldn’t.

“He was in at five o’clock at training two hours ahead of everyone else,” said Leonard. “You could never get there before him.”

Ahead of last year’s All-Ireland final selector Declan Darcy said of his stopper: “He doesn’t talk, he acts it. He does come to training two hours before it starts and he will do it. And he will tell you that you’re not doing it.

“That’s what you want. If your top players are doing it consistently and you have enough of those players in your group then you have a chance of being successful for sure.”

He can often be seen berating his defenders for allowing sloppy scores, even if Dublin are cruising to victory near the end of games.

It’s human nature to want to be liked, but it’s even harder to be respected.

Cluxton arrived on the scene in the early 2000s to a talented Dublin squad that many felt lacked the mental fortitude to win the big prize. Even as a teenager he wasn’t afraid to call others out when he felt things weren’t being done properly.

Pillar Caffrey recently recalled a story from 2002 when Dublin played Donegal in the All-Ireland quarter-final. It was Cluxton’s debut campaign as the number one.

They were missing Tommy Lyons that afternoon after the manager was hospitalised with gallstones, and selector Caffrey replaced him as the number one on the day. The team arrived at their designated meet-up spot in Parnell Park, where Caffrey was met by Cluxton who had “a big long face on him.”

“Everything okay?” Caffrey enquired.

“No, it’s all your fault,” said Cluxton. “The lads’ heads aren’t right. Tommy’s not around and it’s going to be shite today.’”

Like Jordan, Cluxton’s ruthless pursuit of winning drove his team-mates to new heights.

Jordan was 28 before he won his first NBA title in 1991. The narrative around that time was that sure, Jordan was a great player, but he wasn’t good enough to lead his team to a championship like Magic Johnson or Larry Bird.

He averaged 31 points against the Lakers in ’91 and at the time it was regarded as the finest all-around performance in a five-game Finals series.

It’s hard to believe now but at 30, Cluxton had yet to win a Celtic Cross. During the noughties Dublin had some great battles with Kerry, Tyrone and Cork but they never managed to even reach a final.

There were concerns over Dublin’s ability to do it on the big day, right up until Cluxton held his nerve to stick over a last-second game-winning free in the 2011 All-Ireland. They’ve barely looked back since.

Neither man was satisfied with just one title. With that insatiable hunger both possessed they went on to drive their teams to unprecendeted levels of success. A three-peat had never been done in NBA history until Jordan’s Bulls managed that feat. Twice.

Cluxton helped Dublin end a 16-year famine and then captained his county to the first five-in-row in GAA history at senior level, bringing them above the Kerry Golden Years team as the greatest Gaelic football side of all-time.

He reinvented his position and revolutionised football forever with his short kick-outs that became a central part of Dublin’s gameplan under Pat Gilroy and Jim Gavin.

Modern goalkeepers who take frees and go short with kick-outs were inspired by Cluxton. But he didn’t plagiarise. He wrote the book.

Jordan, undersized compared to other stars at the time, tore down the conventions that only big men could dominate the league.

They reshaped their sports thanks to a blend of physical gifts, competitive spirit and artistry. And they possessed a growth mentality when things didn’t go their way.

Jordan was forced to hit the weights and build up his body after repeatedly falling short against the more physical Detroit Pistons in the playoffs early in his career.

After his first comeback from retirement saw the Bulls bow out in the 1995 playoffs, Jordan was in the gym the next day preparing for the following season. There were doubts surrounding his ability to go from ‘baseball shape’ to ‘basketball shape’ at 33, but he went on to reassume his place as the top dog in the league over the next three years.

Following Killian Spillane’s goal in drawn All-Ireland final last year, Cluxton spent two hours on the training field the next day correcting his positioning. He made several key stops in the replay as Dublin achieved history.

“That somebody who’s a master of his craft,” said Jim Gavin after the replay. “Through that example, he inspires people around him.

“Stephen is well able to talk, he’s very articulate and people listen. But how he demonstrates, his actions, that’s what I’m interested in. That’s what he does. He’s a doer.”

There’s every chance Cluxton will use this break to rest his body and come back reinvigorated to scale that mountain once again.

And if he doesn’t, he’ll deservedly take his place on the GAA’s Mount Rushmore.

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!