IN NOVEMBER 2009, just ten months after he announced his retirement from football, Colin O’Brien was inducted into the Cork City Supporter’s Hall of Fame at a function at the Metropole Hotel.

For a player who spent his career desperately trying to avoid adulation and celebration, he was far outside of his comfort zone.

But, during a rare moment of vulnerability in our interview, he admits it meant a great deal to him.

“Getting that award, I was a little taken aback”, he says.

“It was great to get it but I was still very young, I felt, to get an award like that. But, for the supporters to do that…I have to say, it was a very special moment because it wasn’t something I expected so soon.”

It says a lot about his legacy and the imprint he left on the club that the fanbase were so desperate to acknowledge his contribution.

O’Brien, like other players of a similar ilk – rarely get their dues.

Particularly in the League of Ireland, those that do get the plaudits and the headlines are either the prolific front-men or the cult heroes.

O’Brien was neither. But, for over 13 years, he was a warrior. He was a relentless ball of blonde energy with a spate of on-field personas. He could be a dogged, determined right-back. Or a pacy winger who’d run all day for you. Or a calm, composed midfield ball player who’d sit in, set the pace and allow others have the freedom they craved further up the pitch.

For that awards presentation at the Metropole, a video was played featuring contributions from some of O’Brien’s former team-mates.

With him being so adept at playing a variety of roles, John Caulfield felt O’Brien had missed his true calling in life.

“Certainly, Colin O’Brien should never have been a soccer player”, he says – tongue firmly in cheek.

“He should’ve been a model. He definitely would’ve been the number one porn star across Europe. We all looked forward to watching him in the shower.”

I put the Cork City manager’s comments to O’Brien.

The response is withering, droll and very Cork.

Is John trying to tell us something else there, is he?”

A career in pornography may have been a stretch but O’Brien certainly had options from a young age.

In 1993, he was a key part of the Cork minor football team that claimed All-Ireland honours against Meath at Croke Park. In the Munster final against Tipperary, O’Brien was captain.

Alongside him in that group were a litany of future senior stars including Owen Sexton, Martin Cronin and future Cork boss Brian Cuthbert, who was O’Brien’s club-mate at Bishopstown.

The following year, he was called into the Cork Under-21 squad as their All-Ireland ambitions grew. Though he didn’t play, he was part of the panel for both the semi-final and final, where Cork conjured a seven-point win over a Mayo team that featured the likes of Ciaran MacDonald, Kenneth Mortimer and Maurice Sheridan.

“I just had an affinity with Cork sport in general,” he says.

“You’d have been going to every GAA match and every Cork City game at Turner’s Cross or Bishopstown. It was part of your identity, really.

“I was just brought up playing football, Gaelic football and hurling – that’s just how it was. Back then you were able to play because of the way the seasons were – into the summer you’d play your Gaelic and it was great because you were active for 10/11 months of the year. So I was able to play all three sports, really, up until I was about 19.

And that’s when I had to make a choice. By that stage I had broken into the Cork City first-team which was a big aim of mine but the demands were becoming greater and it was getting harder to commit to GAA. But I had good innings with the other sports and it stood to me because I was a late developer, physically, unlike the majority of the other lads when I was younger. At 17/18 I finally got my growth spurt and it all came together. But playing all those sports helped me with that, certainly.

It was my choice. It was what I wanted to do. And that’s what I say to young players now – you can’t be forced into decisions by coaches. But my coaches were very good and always wished me well. It wasn’t awkward or anything and just something I had to do at the time.

When City set up a youth team…that’s one of the things I was very proud of. At the time, they had a youth team, a reserve team and a first team. And at a very unstructured time in terms of coming through, I came through the U-18s, played in the reserves and then got into the senior team. I always hold that close to my heart – I played for the club right through.”

And the mementoes from such a decorated underage GAA career? The medals, the jerseys, the photographs?

That’s probably my Mam – she’d have a few of those things. The parents would hold onto those things. But my mindset was firmly – ‘Let’s move onto the next project.’”

That next project was City, where he had come through the ranks to the fringes of the first team. O’Brien had grown up in the stands, obsessing over the team and the players. Even now, over a quarter of a century later, finishing as runners-up to Dundalk in 1991 on the final day of the season is recalled with a sense of bitterness.

“When (Tom) McNulty scored that goal and broke our hearts, when all we needed was a point at Turner’s Cross…I remember being there that day. I saw some tough ones but also have some great memories.”

Ironically, the club’s tough days resulted in him getting his chance with the senior squad. After a championship success in 1993 under Damien Richardson, City began to veer out of control. Richardson left in 1995 as off-field disputes with the boardroom coupled with the disastrous move to Bishopstown led to an untenable situation.

Ahead of the 1995/96 campaign, the club appointed former Sunderland and Derby centre-back Rob Hindmarch as player-coach. With City owing huge money to a variety of creditors – including the Revenue – it was chaos and a baptism of fire for the string of players that arrived from the UK like Melvyn Capleton, Paul Wimbleton and Gary Castledine. Inevitably, they weren’t there for long and neither was Hindmarch.

Still, it was during this turbulent period that O’Brien made the step up.

“The club had fallen down a little bit and we were battling relegation that season,” he says.

But it offered a great chance for me and it was a great grounding because nothing was easy at the time. It was away to UCD in lovely Belfield on a November evening in 1995 and played right-back. You always remember it. And it was a great start for me because you weren’t coming into a team that was firing on all cylinders. I began to establish myself in the first-team over the next couple of seasons.”

His flexibility and versatility was an added bonus.

“In the youth and reserve teams, I would’ve played in central midfield and in defence occasionally,” he says.

“But it was right-wing and centre-midfield for the majority of my time. I got my eyes opened up to a few different things. In Europe you’d play a different way again. That’s helped me too. Having played in different positions and systems, it gave me a good education in the game. The likes of Declan Daly and Dave Hill were brilliant. Dave had just come over from England and was a real warrior and gave you some great tips on positioning. John Caulfield, Pat Morley, Patsy Freyne – they all had a great grounding in the game and they’d always pull you aside about something – even if it was a word of encouragement. You need to be told things as a young player and they were very good for doing that and they had their own style of doing it. Which is something I’ve never forgotten.”

Hindmarch, an outsider, hadn’t worked. So, the club returned to the familiar and brought in Dave Barry as manager in 1996. For O’Brien, who had grown up on a diet of Cork GAA and football, it was a fascinating appointment.

“Dave was a big role model for me,” he says.

He played senior football for Cork, a Cork City icon so there was that huge enthusiasm and excitement around. In that first season he kept us up. We didn’t shoot straight up the table. He needed to get us stable, which he did. Then he began to develop things. He got that Corkness back – the squad had that balance with a number of Cork players and that identity returned. We still had players from outside Cork and from the UK and, historically, that was always there with a lot of the successful teams having had that blend. And Dave even brought in other players from around Munster too – Kelvin Flanagan arrived, Stephen Napier, Ollie Cahill.”

The chemistry experiment sparked some progress. Barry got City competing again. O’Brien developed into an excellent right-sided midfielder and with him on one side, Cahill on the other, the club got some momentum going.

O’Brien grabbed a crucial header at the Shed End against Shamrock Rovers that ensured a fourth-placed finish in 1997 and qualification to the Intertoto Cup.

“When I was younger, it was the big European games that would always carry that buzz around school or the community, hearing about these teams coming to play in Cork,” O’Brien says.

“And that history was always there for Cork. To get a chance to continue that, it wasn’t something I was going to let go. The big difference was that you’d know even in the warm-up. The ground would be filling up. That atmosphere was there before you’d even stepped on the pitch. You wouldn’t have that on a league match-day. As a player you knew it was a special occasion. That huge nervous energy. You just thought, Right, this is a big one tonight’.

The very first one I was involved with was a group of five in 1997. Ourselves, Koln, Standard Liege, FC Aarau, Maccabi Petah Tikva and Standard Liege. With league games, you knew what you were going to get. Sometimes they’d be very frantic games. But when I first played in Europe, the big thing was the tactical side of things. You got time on the ball. How they pressed was different. Here, you’d be on the ball and under pressure straight away. Teams could lull you in. You’d think you were doing well and then you’d be picked off 10 seconds later and picking the ball out of your net. For me it was concentration had to be there, even when you had good moments in the game you could be vulnerable – when you thought you were on top. Even going from home to away – totally different games. It was such an insight. You could play at home and people would think, ‘Oh, you did very well’. The tie could still be in the balance ahead of the second game and then the speed over there could go up a few levels.”

Under Barry, the culmination of the progress came in 1998 when City beat Shelbourne in the FAI Cup final thanks to Derek Coughlan’s header.

But, O’Brien missed out on playing that day. Just a few months before, he went up for a header against St. Pat’s at Turner’s Cross.

“You always remember these things,” he says.

“It was a month out from the semi-final of the Cup and I can see it happening even now. It wasn’t from a challenge. I came down after winning a header – I won it cleanly, wasn’t competing with anyone. When I hit the ground, the knee just went to the side on me. And I knew I was in trouble. Declan Daly had it happen a few years before, Dave himself and Liam Murphy too. But it was still new to the country, that injury. There were different views on it in terms of how long you’d be out for. But, I got a great education in terms of rehab that has subsequently served me very well.

The reassurance for me was those players that had come back from it, especially the likes of Deccie. Straightway that was the reference point. You’d hear ‘career-threatening’ a lot but once I saw Deccie coming back and Pat Morley as well, who had it happen too, it gave me great confidence. But you had to deal with the huge disappointment of a big injury – you find out a lot of things about the game and yourself. Looking back, it was tough but not a bad thing in the long-term.

What you lose is the group sessions. You’re away from that for a good few months and you only see the team-mates on match days. But immediately after the operation was done, your recovery programme started. And those first four weeks were probably the defining period in terms of how everything would go. They were the slow burner ones. They were very basic exercises you had to do but important in order to move onto month two or month three.”

Six-and-a-half months later, O’Brien was back. Fit enough to start a game, there wasn’t much in the way of apprehension. The plan had been followed meticulously. Now, it was just down to him.

“I got the all-clear after six months and I remember playing down in Waterford at the RSC in December – a muddy, soft pitch. I got a clatter early on but bounced back from it. It was a huge thing. A tackle. I got cleaned out but I remember just getting up and it was no problem. It was probably what you needed. The reassurance.”

After being pipped to the 1999 title by St. Pat’s, Barry walked away and the club prepared itself for another transition.

Once again, like so often in its short history, everything quickly turned to dust.

“People forget that managers weren’t full-time either,” O’Brien says.

“There’s a huge commitment that they’re putting it. I can still remember Dave’s parting words, actually. He felt he’d brought us as far as he could. I remember that he thanked us all. I think he, maybe, needed a break. When he said ‘This is as far as I can take ye’…he probably really felt he’d given 100% commitment.”

City, once again – despite the issues surrounding Hindmarch’s tenure – looked to the UK once again for Barry’s replacement and brought in Colin Murphy.

Cue more pandemonium.

“That was the time that he took a young man from the Douglas area,” O’Brien says, laughing.

“Big Damien Delaney!”

“When a new manager comes in, they try and put their stamp on things,” he continues.

And what always intrigued me was whether there was going to be anything different on the table. Was there anything different in terms of the way we were going to play? I suppose I was like a sponge that way. I was never afraid of change. I always looked at the positive and ask myself what I could learn. But he lasted six weeks. Pre-season had gone well. It was interesting. I learned a few things and then, he was gone. And Damien Delaney with him. To Leicester. He wasn’t there one night in training. I think it was Liam (Murphy, his assistant) who might have told us, ‘Listen, the manager is moving on’”.

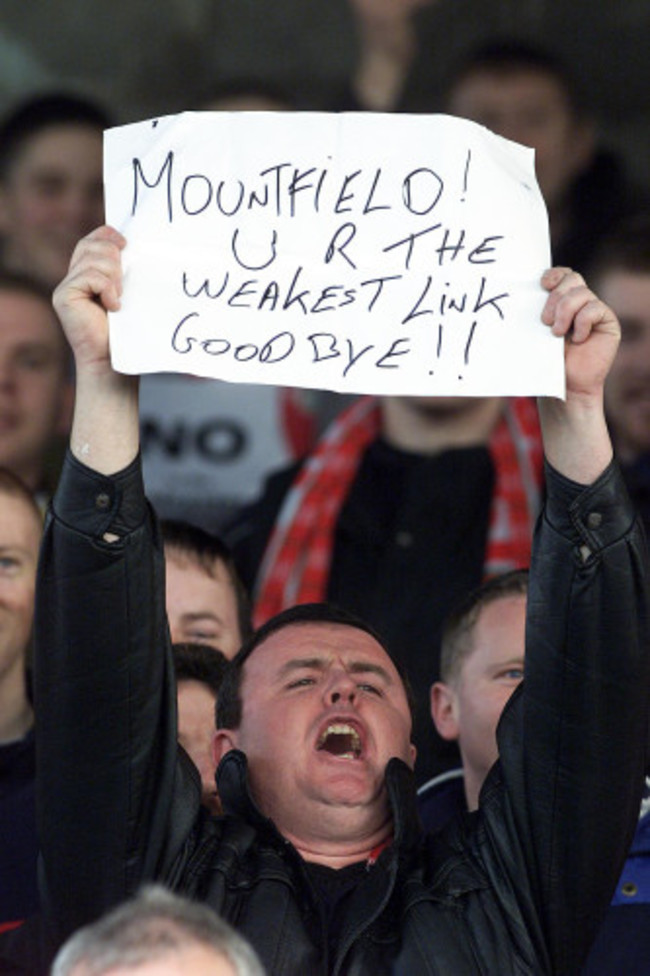

Murphy was at the club for eight weeks and oversaw just one game before taking up a role on Peter Taylor’s coaching staff. With some European assignments approaching fast on the horizon, former Everton and Aston Villa defender Derek Mountfield was appointed as manager.

“He was brought in and I remember coming back from a game against Shamrock Rovers, and we’d got a hammering,” O’Brien says.

“Derek told us that Damien would be leaving for Leicester on Monday morning. And Damien would be the first to tell you that he’d had a tough day up at the Morton Stadium. But he was a young lad, maybe 17/18 at the time. And Leicester saw something – a left-sided player, quite athletic. But that’s how we were informed. And Derek himself only lasted a few months. They tried going for an outsider before Liam then came in and brought some stability to everything.

But I remember really enjoying some of the stuff under Derek. He came late in pre-season and at the time you would’ve heard about Speed, Agility, Quickness – this SAQ stuff that exploded a few years later. But he introduced it to us at the time and used the ball a lot in our training – even in our conditioning – and I found that pretty intriguing. He introduced us to playing 4-3-3 and that’s worldwide now. Everyone was going 4-4-2 here. But, unfortunately, he was on his own here, and didn’t really know the league. He was trying to make his changes but inevitably we just didn’t get the results.”

After a long-term stint as deputy to Barry and those that followed, Liam Murphy finally stepped up and took the reins. Younger players, like John O’Flynn and George O’Callaghan were enticed back from the UK and were eager to prove themselves again. City played a good brand of football but still fell short when it mattered.

“It was important for the club to get the stability back – similar to what we had under Dave,” O’Brien says.

“We’d go on some great runs, particularly that first season Liam took over. But we always let ourselves down against teams we should’ve beaten. The league was still very tight with five or six teams that could push for places. So it would’ve been a frustration at the time.

George had the attitude that he was the best player on the pitch. He was very good on the ball, creative and then with John, you just knew. His movements – even in training – were superb. And they, and the likes of Dan Murray who’d also come in, brought a bit of freshness to the whole thing.”

When Pat Dolan arrived, there was expectation, investment but still no title. By that stage, O’Brien was already a few years into his job as a Development Officer with the FAI. It was a balancing act but he didn’t shirk the added pressures.

“I was always interested in that side of the game, particularly working with younger players. I started with the FAI in February 2000 and it’s like any job – you need that first year to find the balance. I knew it would be a challenge – the same as it is for a lot of people playing sport at a high level and who are also working. You’re going seven days a week. It’s what goes with the territory. You know you’re not going to be playing forever and you want to get the maximum out of it.

Pat certainly put more demands in place. More players were full-time. Over two seasons, I could probably count on one hand those that weren’t. He laid the foundations in pre-season. You’d go away for camps and do double or triple sessions in a day. The abiding memory would’ve been the conditioning. It would’ve been a big part of his setup as manager. He wanted us to be one of the fittest teams. And in his second year, I think it was the best condition I was in as a player. But it took you that long. There was always another level to get to.

You know it’s not going to be forever. But the biggest difference was recovery. If you had a tough game on a Friday night or a heavy, intense session during the week, you’d have a recovery session on a Saturday morning. But the big thing about recovery is that you need to be off your feet. I might have done a recovery session but I was still on my feet for Saturday and Sunday doing my coaching. So, inevitably I would’ve felt my energy should’ve been at a certain level coming into Tuesday but it wasn’t. For the other players, they were in better shape early in the week. So, looking back, you’d have liked things to have been a bit more individual.”

Dolan was controversially sacked just weeks before the start of the domestic campaign. He had been there for two years, curating a superb side that played excellent football. But, it was under Damien Richardson, when O’Brien finally claimed a League of Ireland winner’s medal.

Was it an obsession? After almost reaching the summit so many times?

“Yes,” he fires back, without a second’s thought.

“100%. We had the nearly years, a couple of runner-up spots. So there was always that kind of frustration. We’d be close and then have a dip and it’d be gone. It’s the ultimate prize in our league. It was something I was determined to get.

And the way we won the league – the fact it was the last game of the season – we were able to enjoy the moment. I was always one to move on as quickly as possible. But you just couldn’t have written that script, really. A special memory – one I’ll always cherish.”

O’Brien would win the FAI Cup in 2007 before everything went off the rails again. In his case, he missed out – thankfully – on the bulk of the Arkaga saga and subsequent Tom Coughlan pantomime. But, he was still exposed to the whispers and could see history repeating itself.

“It was like the full cycle for me, really,” he says.

“It was bizarre. I had gone through a lot of it in my early stages of my career in Cork. We won the league and then the bubble began to burst. Full-time was beginning to break, the financial situations were becoming widely known, the difficulties the club was in, etc. There was too much going on. Too much uncertainty. On my side, I had my job. But for the lads – where football was their only source of income – it was a very difficult time.

I think we were introduced to somebody from Arkaga at training one time. Players aren’t fools. Sometimes you get an impression based on what someone says or doesn’t say. It just didn’t fit with me at all. Rumours about them were circulating. It just didn’t fit, simple as that. There was no conviction for me. I’m not sure if they had enough of their homework done going by some of the things they were saying. I didn’t get the feeling they were in it for the right reasons and for the future of the club. I just didn’t feel it at all.”

O’Brien was also struggling with a new role: substitute. Under Alan Matthews, he just wasn’t featuring. In 2008, with a new coaching role within the FAI to contend with, he began to weigh up his options.

“I gave Cork six months and I didn’t feature, I didn’t get opportunities,” he says.

“A few things had changed with my work. I had got into a new role that was more national so there were new demands. I knew at the end of the season that I’d be finishing up. I just wanted to play so I went to Cobh Ramblers for six months.

At the time it wasn’t so much a tough one for me. I know I contributed to Cork and to the history of the club. It was just a matter of me wanting to play football. I was at an age where I needed to be playing. There were no fall-outs with Alan and it was just about getting back on a pitch. But I knew it would be impossible to meet the demands of playing in the League of Ireland going the way I was going.

My club would’ve always been Cork. I’d given everything to Cork. I tried, for six months, to get in. Football always came first for me and I wasn’t playing it. I wasn’t a player to sit there and pick up a wage packet and not feeling I was contributing. Whether it was Cobh or somewhere else, it wouldn’t have bothered me.”

O’Brien, inevitably, distances himself from being dubbed an ‘unsung hero’. He doesn’t want the praise or the pomp.

“It’s nonsense. I had a role to do. You’d come in, train, you’d know when to have your banter. I was just extremely proud and honoured to play for my team in Cork and I just loved it. It was the education I got from it. It wasn’t always great. We didn’t win the title every year, my form dipped or I was out of the team. But the education I got on the game and life…so many things I learned that I’m passing on now.

Regrets?

“There’s always the tinge…especially those battles with Pat’s and how close we were for two years in a row and the deciding games being the ones you played against them. Definitely we should’ve won one of them but didn’t. There will always be that little bit of regret. But we got one and we’ll cherish that. I’m really grateful for the education I got. On my own curve as a player – it all happened for me here and stood to me in my personal and professional life.

That’s probably the greatest compliment I can give Cork. ”

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!