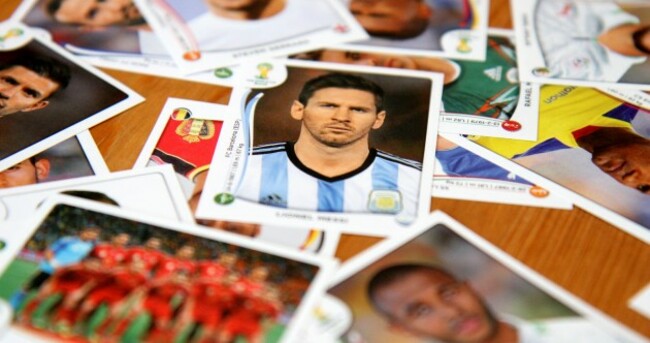

SOME WEEK’S AGO the BBC did a provocative feature that I’m sure would be a trip down memory lane for many. The article documents adult males’ fascination with collecting football stickers as children and recounts the days when building albums of mug shots was your greatest concern.

Myself and my brothers were avid collectors as children and I was fortunate enough to complete the 95/96′ and 97/98′ Premier League Panini/Merlin editions at the tender age of 9.(I don’t think I will ever forget the feeling of desolation tirelessly searching for the Middlesbrough defender Steve Vickers for over 3 months to complete the 96′ edition).

Looking back, the playground really becomes a laboratory for thinking about ‘intuitive economics’, as children as young as five and six get one of their first experiences of autonomous market transactions (as a watchful parent is nowhere to be seen). It is probably one of the first arenas where our independent economic socialisation begins. Previous research (linked below) suggests that swapping seems most popular during middle childhood, between the ages of 8-10 and generally takes place at school. By approximately 12 years of age children show a tendancy to ‘grow out’ of swapping.

Anyone familiar with the process of collecting stickers will understand how you build a bank of ‘swaps’, essentially duplicate stickers to exchange for players you need. While it’s been quite a while since I was in primary school, I’m sure the lunch time break still gives kids that window of opportunity to get the necessary deals done, exchaning their swaps in an effort to have the prestigious title of finishing the collection first.

Looking back on my own experience it surprises me how young children have such a strong intuition for many econ 101 concepts. Whats more, a marketplace for stickers naturally comes about, devising its own specific prices and norms along the way. Children learn that scarce resources that are in demand come with a higher price quite quickly as rarer ‘shiney’ stickers with glitter surrounding a clubs crest or star player have a different exchange rate and only trade for a higher price of 2 or more ‘normal’ stickers depending on demand.

The rarest sticker was, of course, ‘number 1’ the premiership logo, that was in greatest demand and held the highest price. If one was lucky enough to get a duplicate/swap ‘number 1’ sticker at an early stage of the season they were almost granted monopoly rights and could sell it for an extremely high swapping prices (I have a faint memory of one child trading what must have been over 100 stickers for ‘number 1′).

As the days went on however more duplicate ‘number ones’ would enter the market and the price to trade for the illusive Premier League crest,would fall.

Equally from recollection the playground market for stickers as time passed got close to a perfect one. Information on product quality was fully observable and could easily be checked, and information would disseminate quickly as to who had what swaps on offer and who needed what stickers. Little scope for arbitrage existed and the law of one playground price ruled near the end of the season.

I hope all those like me will enjoy the nostalgia in the BBC article and the thought that we may have been acting like an economic agent of our textbooks even before we knew it. In truth the economics of swapping stickers reminds me of how many interactions can take on an economic form but essentially have a social function.

There is a reasonably large literature on the relationship children have with economic concepts but for specifics the 1996 article by Paul Webley, Playing the market: The autonomous economic world of children gives a good overview of the economics of childhood swapping. For those with a passion for Gaelic Games, John Considine provides some more nostalgia here, recalling the experience of buying his first hurley.

David Butler lectures economics in University College Cork and regularly writes at www.sportseconomics.org.