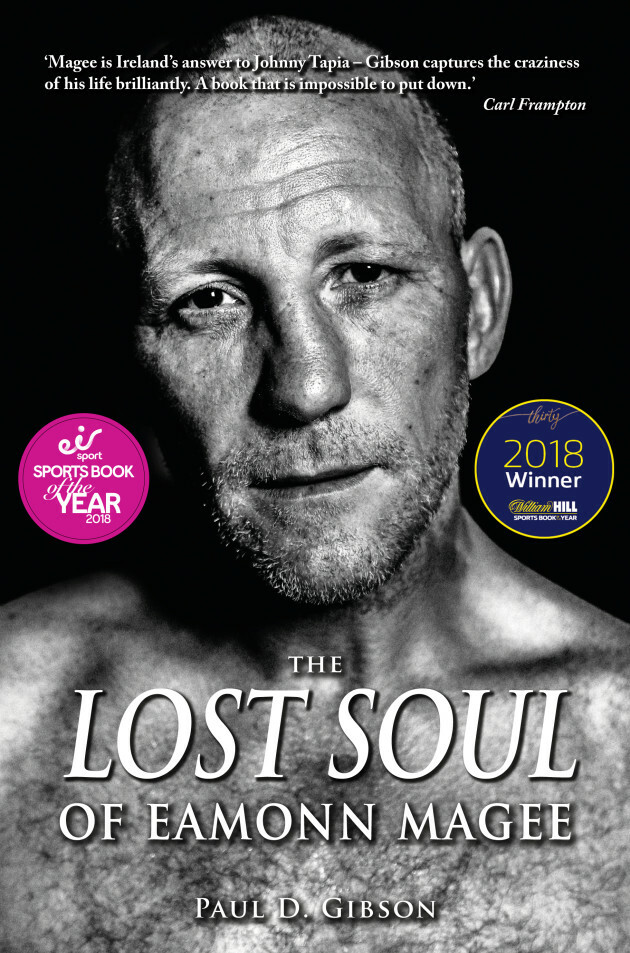

THE FOLLOWING PASSAGE is an extract from ’The Lost Soul of Eamonn Magee’.

Just three fights in a year afforded more free time than it was safe for a man like Eamonn Magee to have. Particularly when that sixty-seven minutes of action paid handsomely enough to indulge in the vices that Eamonn had always found impossible to ignore. Drink, drugs and infidelity were still a constant in his life and placed a devastating strain on his relationship with Mary and the kids. On occasion Mary inevitably lost it and the resulting rows would be ferocious and, at times, physical. In the aftermath, Eamonn would storm off and not be seen for days, leaving her to pick up the pieces and attempt to maintain at least a façade of normality for the children’s sake.

Once, when Francis, Áine and Eamonn Jr had been left at the school gates, Mary returned home, packed all of Eamonn’s clothes in black bin bags and deposited them in a charity shop on Castle Street in the centre of Belfast. A couple of days later, Eamonn was walking to the gym when he noticed the shop-window mannequin dressed from head to toe in what looked suspiciously like his own garb. Upon entering the store, a quick scan revealed his entire wardrobe for sale at knock-down prices. He bought it all back and returned home to an empty house where he proceeded to cut a chunk out of the side of every one of Mary’s dresses. They’d later kiss and make up, and it never crossed Eamonn’s mind that, one day, Mary would surely lose all patience and decide to be rid of him for good.

The abuse of various substances sparked much of the trouble Eamonn found, but, in truth, he was an extremely high-functioning alcoholic. He admits that a heavy night on cocaine left him less than 100% the following morning, but he could put away any quantity of drink and pills and wake early the next day to hit the gym or go about his business with no ill-effects. This was a blessing at face value, but an undoubted curse in the long run.

Mike and John did not know about the full extent of the drug problem, but they were well aware that their prized asset was overly fond of the drink. That was a large part of the reason for spiriting Eamonn away to isolated farmhouses in the countryside in the build-up to big fights. For added security, Callahan would leave handwritten notes behind the bars of any pubs he suspected Eamonn of frequenting, begging the staff not to serve the boxer if he had a fight in the coming weeks. Eamonn could be persuasive, however, and there were always new drinking establishments to explore anyway.

On top of the substance abuse, another demon had by now tightened its destructive grip on Eamonn. From the moment he had a few coins in his pocket as a kid, Eamonn loved the thrill of gambling. And from games of pitch and toss for a handful of loose change in the school yard, it wasn’t long before local bookies became familiar with the flame-haired punter popping in and out throughout the day to bet on anything from horses and tennis to football and the GAA.

***

On the day I meet his brother Patrick, I drop Eamonn off at a local social club that offers cheap and early pints to pass the morning. In what is unlikely to be simply a happy coincidence, Sean Graham has a branch of his bookmakers next door. When I arrive after a couple of hours with Patrick, I bump into Eamonn dashing out the door with a grin on his face and a winning docket in his hand.

‘Go on in and get a pint,’ he shouts as he jogs out of the car park. ‘I’ll be back in a sec.’

It is a standard set-up inside the low-ceilinged club. A well-stocked bar, a well-used snooker table and large screens on the wall showing Sky

Sports news and the racing channel. Eamonn soon returns and picks up where he left off with the pint of Harp on the bar.

‘How much did you win?’ I ask him.

‘Ah, a few quid,’ he replies, before motioning up to the screen. ‘It’s all on the favourite now.’

Looking up I ask him what his horse is called, but he never pays any attention to the names. All he knows is it is number five and the wager and odds were good enough that it’ll cover all our expenses for the day.

He’s an all-or-nothing type of guy so needless to say, he only ever bets on the nose. With pints in hand we watch the 15.10 at Ludlow commence.

It turns out that number five is called Duke’s Affair and he is going along nicely until number four, Minellacelebration, comes up the outside and beats him by a length.

‘Fuck that then,’ Eamonn mutters as he rips up the betting slip and tilts his empty glass towards his nephew working behind the bar to signal another pint is required. Easy come, easy go.

In the grand scheme of things he didn’t lose much that day, but only because he didn’t have much to lose. But back when boxing was paying Eamonn well, he became well known in gambling circles for regularly staking £20,000 on the outcome of a race or a match, and at times betting double that. He has plenty of winning stories but as usual it’s the hard-luck tales that stick in the memory. There’s the untimely last-minute point in an All-Ireland final that he had £40,000 riding on. There’s the grand he lost when the jockey inexplicably slid off his horse when he cleared the last and was cantering home with nobody near him. There was the family weekend in Leopardstown when he lost every penny at the races and the police were called when he couldn’t pay the B&B bill. In amongst those extremes there is a decade’s worth of constant, if unremarkable, gambling that he now estimates saw close to a million pounds lost and won and lost again.

‘A gambling addiction is a really terrible fucking thing,’ he tells me as we drive out of the car park. ‘It can control you every bit as bad as the drink and the gear. It can trick you into thinking that money grows on trees and so it doesn’t matter if you lose, you’ll get the money back again soon one way or another. And that’s what I believed back then – that there was always another score, or another win, or another big purse just around the corner.’

I don’t want to be a world champion, I want to be a millionaire, he said before the Neary fight. Accumulating that amount of money was more than a desire; it was a need. Each time he got in the ring and fought for a purse of money he was chasing the losses that were just around the corner.

‘The Lost Soul of Eamonn Magee’ by Paul D Gibson is published by Mercier Press. More info here.