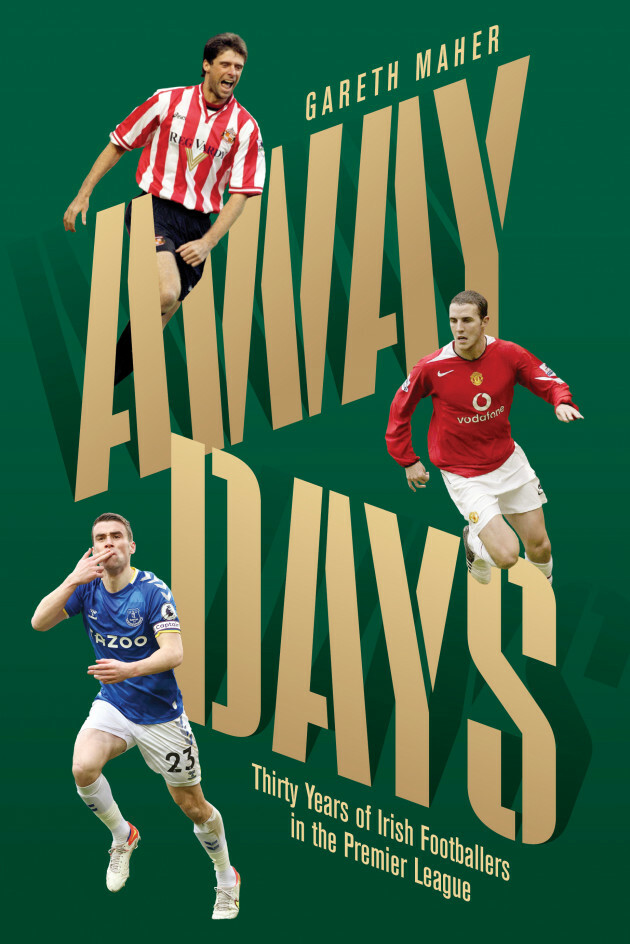

THE FOLLOWING PASSAGE is an extract from ‘Away Days: Thirty Years of Irish Footballers in the Premier League’ by Gareth Maher.

The career of a professional footballer is often compared to a rollercoaster ride with adrenaline-filled highs followed quickly by soul-searching lows.

Jonathan Walters certainly knows how that feels, having started out in the Premier League, before dropping three levels down to League Two and rising back up again to the top.

Walters, therefore, is someone who can accurately provide an insight into life as a Premier League player. And in many ways, that perspective can be broken down into three stages: The Good, The Bad and The Ugly.

The Good

Nothing beats that first appearance. For a footballer to make their senior debut, it is a stamp of approval that indicates that they have made it. Walters got that with Bolton Wanderers in the 2002–03 season when appearing as a substitute in a 2-1 loss to Charlton Athletic. He went on to feature in four Premier League games for Bolton before his career took another direction.

Walters, who grew up in Merseyside, started out with Blackburn Rovers. “I was at Blackburn as a youth and I was actually top scorer in England for my age. We got to the Youth Cup Final in my first year and I scored. I think I scored 38 goals that year and I had never been in an academy before. Then I left and immediately went into the first-team squad with Bolton and was pretty much on the bench every week. I was given squad number 12 and I was like “bloody hell”, I was immediately thrust into that side of it.

“It was mental because the team that they had was full of great guys like Colin Hendry, Per Frandsen, Henrik Pedersen, Kevin Nolan and Jussi Jääskeläinen. Then you had Youri Djorkaeff who had just won the World Cup [in 1998 with France].

“I was still a kid and I don’t think I grasped it as much as I should have. It goes back to home life because I didn’t have much of a home life. I wasn’t living right … not in a bad way, I just spent as much time away from home as possible.

“I went on loan to a few clubs and I had two years left on my contract at Bolton but I asked to go to Hull because I had that taste of playing every week. Now I look back and think: what was I doing? Stay as long as you can at a Premier League club. I don’t have any regrets because my career turned out how it turned out. But maybe it would have been slightly different if I had stayed at Bolton.”

It didn’t happen straight away, but Walters learned over time that it was the simple things that led to success. He discovered that maintaining a disciplined lifestyle, following a healthy diet and working as hard as possible in every session was the best way to enjoy consistency as a footballer. It is what helped him return to the Premier League six years after leaving Bolton in 2004.

The period that Walters spent in the lower leagues was full of uncertainty and off-field issues, but he did enjoy some good times, played a lot of games and discovered a hunger to be the best version of himself.

“People always ask: ‘Did you know that you were always going to get back there?’ I always believed in myself but my focus was always on the team that I was in. I had a young family at the time so your focus is more on a week-by-week basis rather than on long-term targets.”

Following pit stops at Hull City, Wrexham, Chester City and Ipswich Town, he eventually did get back to the Premier League when he joined Stoke City in 2010.

In his first season there, he finished as the club’s joint-top goalscorer and proved that he belonged at that level. He would go on to play over 200 times for the Potters and establish a rapport with the supporters, who still view him as one of their best players of the Premier League era.

It was during his time at Stoke that Walters became a regular starter for the Republic of Ireland, scoring 14 goals in 54 appearances, playing in two Uefa European Championships and picking up the FAI Senior International Player of the Year Award in 2015.

There was also the FA Cup run in 2011 that brought Walters and Stoke all the way to the final at Wembley. They narrowly lost 1-0 to Manchester City but the statement was made that Stoke had the ability to mix it with the Premier League’s top teams. They proved to be a nightmare opponent for Arsenal for many years, while there were also a couple of notable victories over Liverpool.

Walters was the team’s most consistent performer for at least six of his seven seasons at the club. During that period he set a new club record of 61 consecutive appearances in the Premier League. The £2.75million that Stoke paid Ipswich for him was clearly money well spent.

Money became a by-product of thriving in the Premier League. The better he did, the more handsomely Walters was rewarded. Or at least that is how people on the outside would imagine it to be.

In reality, he was nowhere near any of the top earners in the league despite being his team’s best player for several seasons.

“People often judge a player by what they won in their career. If you need trophies and winners’ medals to tell you that you’re a success it’s not quite right. I understand that you want to be at the highest level but to get into the Premier League, to help set up my family and to help a lot of people less fortunate than myself, I’ve made a success of myself.”

The Bad

Sometimes the bad isn’t that bad at all. Take the Chelsea game on 12 January 2013 as an example. It should be marked down as Walters’s worst-ever game as he scored two own goals and missed a penalty in a 4-0 defeat. It was a whole new level of embarrassment. Except the aftermath of that game made him think twice about what constituted a truly bad experience.

“First of all, I’ve scored the own goal. I think I’ve ran past three people to get the header in, it was a good diving header actually! Then I kicked the ball at my own face, scored another own goal and missed a penalty. I can either sulk about it and be down about it or you can realise that it’s not that big of a thing when you think about some of the really bad things that happen in life. I remember going home and the kids taking the mick out of me, putting it on telly and laughing. We just laughed it off.”

Before he got home, Walters apologised to his teammates in the changing room directly after the game and the manager, Tony Pulis, summoned him to a meeting the next day.

The burly forward expected the worst from his manager and he did volley some verbal abuse in his direction but it was more playful than venomous.

Walters was relieved, at least until Pulis informed him that he had to do an interview about the game. The last thing that he wanted to do was talk about his error-ridden performance in the media, but there was a catch — the fee associated with the interview would be donated to the Donna Louise Children’s Hospice. This was a way of turning a bad experience into something good.

Still, the suffering wasn’t over just yet for Walters. Initially, he was due to sit out the midweek cup tie away to Crystal Palace but Pulis felt that it would be good for him to play, to get the bad vibes out of his system. The Palace fans were licking their lips in anticipation of seeing the Stoke striker so they could not so kindly remind him of his Chelsea nightmare.

As he trotted onto the Selhurst Park pitch he was greeted by a chant of: ‘He scores when he wants.’ Walters cracked a wry smile, appreciating the sense of humour. Then he went and scored twice to silence them.

If positives can be taken from performances — no matter how bad they are — then the really bad side to the Premier League shows up in how brutal it can be as a business. Players are often seen as pawns, readily sacrificed when clubs are making bigger moves.

“As you start to play in the Premier League you come to the realisation that the club is looking to replace you. No matter you who are, what position you play or how well you’re doing, the club is always planning to replace you. I was very conscious of that and it’s why I played right-wing, left-wing, in the Number 10 [position], up front and even in midfield because I was willing to do the work that others wouldn’t do.

“I remember one year I scored a silly amount of goals and I had a year left on my contract and asked my agent about it. And they said: ‘Yeah, we’re not going to look at that now.’

“So I carried on but a few months later we got around to negotiating. I wasn’t asking for the top wage because I knew that the club were bringing in some very good players on very high wages. But it dragged on and then it looked like I might have to leave the club but I didn’t want to go. In the end, it got sorted and I signed a new deal, but I remember Tony Scholes [chief executive and director of the club at the time] — who is a great guy — saying to me that it was just business, it was never personal.”

The Ugly

Walters is a family man. He spent his playing career living a quiet life away from the pitch. Part of that was due to his daughter Scarlett being born with gastroschisis — a birth defect in which the baby’s intestines extend outside the abdomen — so that required a lot of hospital visits and close attention during her early years.

An uglier side to the Premier League, however, was in how players could be treated like machines: perform to the required level or else find yourself on the scrap heap. A bad side was when players were let down with contracts or by being moved on, but it got really ugly when they were dismissed altogether.

Walters feels that players do not receive the kind of support that they require — both during their careers and after it. It is why he applied to become CEO of the Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA) in 2021.

As a player, he served on the PFA Management Committee and regularly voiced his concerns about the need to provide a better support structure for players. He believed that, as CEO, he could have implemented the kind of changes that the association and players throughout the football league in England needed.

‘There are so many lows in football and you’re lonely a lot. Trust is a big issue in football. You are close to your teammates but there is such a turnover that it’s hard to stay close to everyone.

“I think players have trust issues because a lot of people outside of football will try to take advantage of you, especially financially, and they will see you in a certain light. It’s ridiculous the amount of players who’ve gone bankrupt and get divorced, so there is an issue there that needs addressing. One of the reasons why I went for the PFA role was that I want to help people and help players. I don’t think the help is good enough, I really, really don’t.

“You can see why so many people go through so many issues because you’re part of something for 20 years and suddenly you’re not. No matter how much money you’ve got, you can quickly go through your money. You’re quickly forgotten about by the players you played with, by clubs, by managers, etcetera. There is no after-care for footballers.”

Walters has been through the good, the bad and the ugly. Yet he prefers to focus on the positive things that the Premier League has given him. And that is why he will continue to fight for better standards for players, so they too can experience the things that have transformed his life.

‘Away Days: Thirty Years of Irish Footballers in the Premier League’ is published by New Island Books. More info here.