BILLE JEAN KING, the iconic and revolutionary female tennis player, once said: ”Sports are a microcosm of society.”

With Brexit, the election of Donald Trump and the rise of various far-right parties, racism clearly remains an issue in modern times

Therefore, it is not surprising that sport has reflected this tension in recent years.

In America, there was the Colin Kaepernick saga.

In England too, racism has often reared its ugly head. To cite one example, last December, Man City star Raheem Sterling convincingly argued that elements of the media “help fuel racism”.

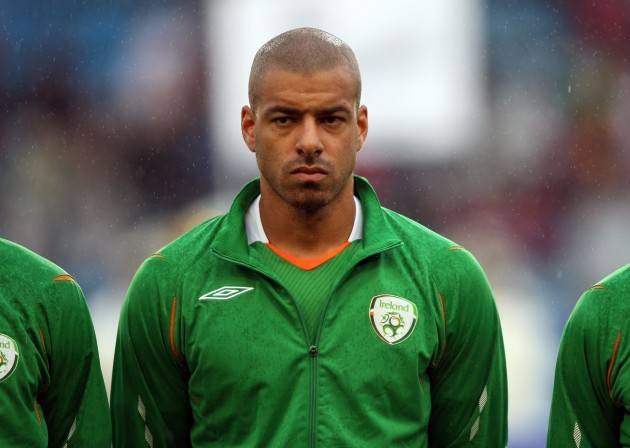

In addition, Ireland has not been an exception to this trend.

Following the national team’s defeat to Denmark in the 2018 World Cup qualifiers, defender Cyryus Christie spoke out after being targeted for racist abuse by online trolls.

More recently, ex-Munster star Simon Zebo was subjected to racism during Racing’s Champions Cup clash with Ulster at Kingspan Stadium in Belfast.

Given these various controversies, The42 recently spoke to two of Ireland’s top athletes about their personal experiences and beliefs in relation to racism.

Gina Akpe-Moses was born in Lagos to Nigerian parents, but her family moved to Ireland while she was still a baby and she has gone on to represent her adopted country in athletics. At 19, she is considered a sprinter of immense potential, having already won silver in the 2016 European Athletics Youth Championships and gold at the European U20s the following year. She also was part of the 4 x 100m Irish team that won silver at the Youth World U20 Championships.

Akpe-Moses initially lived in Athlone before moving to Dundalk when she was “five or six”.

“I moved with one of my best friends. I never felt alone. We made friends easily. Everyone was quite welcoming. Even as I grew up, I never felt self-conscious.”

Growing up, however, she felt there were subtle issues.

“If I did notice anything, [boys] were more attracted to the white girls than me. It’s just the way it is, people’s preferences. So I can’t really say anything.

In the society we live in, race is a big deal, but no one wants to address it. They’re used to seeing white girls, so they’re automatically going to be conditioned in a sense to see that as attractive.

“So when you see a black girl, she’s different, she’s not used to what you see — blonde hair, blue eyes, that kind of stuff. But I’ve got kinky hair, braids, brown eyes and dark skin tone — they’re not used to it. Some people may like it, some might not. It’s just how you’ve been brought up — I don’t think it’s ever intentional.

“I never got any hate as in: ‘Oh, she’s black.’ But if you put me and a white girl in front of the boy, he’d obviously choose the white girl, because that’s what he’s accustomed to.

“Dundalk itself was a lot more white-based than black-based. If I was in Dublin — a bigger city where there’s a bigger congregation of everyone, you’d definitely see more of a mixture.”

Despite these problems, Akpe-Moses says Ireland always “felt like home” and she rarely encountered racist abuse.

“I’d hear stories, bits and bobs, but I was never exposed to it,” she says.

As she grew up, however, her understanding of racism became more nuanced, while joining social media also opened her eyes to people’s backward mentalities.

Once, to celebrate an athletics triumph, Akpe-Moses mistakenly put the Irish flag the wrong way round in a picture. An innocuous error, yet one which was seized upon by ignorant trolls.

“So obviously, it comes: ‘She’s black. She’s not Irish. Blah, blah, blah. This is why she’s got the flag the wrong way round.’ I have seen it online and I’m like: ‘What the hell?’ I just got a medal for my country, so why am I being scrutinised over the colour of my skin for accidentally putting my flag the wrong way? It’s never been face to face. It’s always been through social media.

“They’d never have the guts to say it to my face. It never affected me, because I would just think, if I was in front of them, they wouldn’t say it to me. So why should I be bothered if you’re saying it to me over a screen?”

She continues: “I’ll never understand racism. At the end of the day, we’re the same. The same blood flows through our veins. Inside, we have the same bones and everything. The only difference is black people have melanin — the pigment white people don’t have and it’s that simple. That’s it. So when people say, ‘I don’t like you because you’re that colour,’ I’m thinking. ‘There’s no actual logic behind it.’ I’ll never understand it.

I think it’s fear as well. When you’re scared of something, you’re automatic reaction is to not like it or to try to get rid of it — you’re in defence mode. They might be scared or they just don’t understand the concept of being black. ‘Maybe you’ll go away if I’m mean to you.’

“You don’t have to be black, you can be a Muslim — religion comes into it loads as well. Or if you’re from Lithuania or Romania, you’ll still get racism.”

In 2014, to further her athletics career, Akpe-Moses moved to Birmingham to join top athletics club, Birchfield Harriers. Compared with Ireland, in Britain, she feels racism is “drawn more towards people who are Islamic”.

She adds: “That’s why there’s quite a lot of racism — there’s a fear of ‘he’s Muslim, he might bomb people’. That’s the mentality here that I’ve noticed.”

Akpe-Moses has spoken before about her memories growing up in Ireland and how one day, she got into an argument with someone in her estate.

“He decided to use the ‘n’ word on me,” she recalled. “I was like ‘whoa’.

“I flipped out, I was like: ‘What the hell?’ I did fight with him. I was quite feisty as a young one. I didn’t really take anything from anybody.”

She continues: “People will always say hurtful things, the best thing to do is just sweep it off your shoulder and let it go. You’re put on this earth to accomplish something yourself. People will come and go. No one’s ever going to be completely nice to you. You’ll always have negative people in your life — just get rid of them, don’t let it affect you and carry on. Life is too short.”

Rianna Jarrett is a 24-year-old Irish international footballer. Like Akpe-Moses, she is highly talented and made substantial progress at a young age. By 15, she was representing Ireland internationally at U17 level. At 21, she made her debut for the senior national team. Since then, a number of unfortunate ACL injuries have slowed the young striker’s progress to an extent, though she was back representing the Irish side last year, starting the final World Cup qualifier against Northern Ireland, having overcome numerous setbacks

Last November, Jarrett was named the WNL Player of the Year, having scored 27 goals in the most recent campaign, in the process helping Wexford Youths claim a league and cup double.

She comes from a mixed-race background. Her mother is Irish, while her father is Jamaican. Jarrett was born in London, while her family spent the early part of her life alternating between Bristol and Wexford. Around the age of 10, she settled in Ireland, living there with her cousins and two brothers.

“So there were a group of us around the same age,” she recalls. “We’re from Wexford Town and we lived in the town, always out playing with the lads and the girls. There’s always been people around.”

Jarrett lined out for local team North End United and played a mixture of boys and girls football growing up, before making the Leinster Schools team and eventually moving on to the Irish underage set-up.

Racism was never a major issue when Jarrett took to the pitch, nor was it non-existent growing up.

“I wouldn’t have [experienced it] in the women’s game. I don’t know if that’s because girls are not as mean as boys. My brother Jordan, he would have experienced a good bit playing soccer in school, even on the playground. It was a trigger point to him — if you said anything about being mixed race or black, he would get angry over it.

“They knew they’d get a rise off him, because boys are like that. With girls, I’ve never had anyone say it to my face. I’ve never experienced that. But I do always know, mam always had conversations with us that ‘people will say stuff just to get to you’. They will target you. Especially in Ireland, when we were younger, it wasn’t as multicultural as it is now.

I remember mam telling me when he brought back dad to Ireland, he was one of the first black people seen in Wexford. It would have been early ’90s. He did get stares with people looking — my grandad brought him to the pub the first day he was there, which was a bit of an ice breaker.

“But mam always told us growing up that people will say stuff and not to get too offended or to take it to heart. Just to be aware, so that we weren’t too naive going into life.”

She continues: “We played one game up the country somewhere. My cousin Saoirse, who’s mixed race as well, was on the team. I was 13 or 14 at the time, we were playing with the women’s team. They tried to protect me at all games, making sure I don’t get injured or hurt with people picking on me. I do remember a few comments were thrown towards me and Saoirse about the colour of our skin and stuff like that. I know Saoirse did get into a bit of a scuffle over it. Then it was only on the way home that I realised what had gone on. I don’t know if it was targeted at me and her. I know she got the brunt of it and took a bit of action there.”

Jarrett has a friendly and non-confrontational personality, and so tends to be calm even when faced with ignorant opinions and attitudes.

“People have passed remarks if we get into an argument, or sometimes people just say it to say it. But I wouldn’t be the one to pay too much attention to it.

“My brother, I wouldn’t say he attracts the attention, because you don’t really attract that attention to yourself, but I do know people know if they say anything to him, they will get a rise off him. I don’t know if it’s just with boys, they’ll get into arguments and they’ll just say whatever comes to mind.

“I don’t really get into arguments or anything like that, so I’ve never come across it. But growing up, people passing remarks in general, they might not even see you there, just passing racist remarks. They might see something in the newspaper or the telly, I do remember that sort of stuff. Nothing aimed towards me in general.

“I suppose I’m fortunate enough. I don’t know if I’m oblivious to it all, or I’ve never been around that background or around people that are racist.

Growing up in inner-city Bristol, there were always ‘stop racism’ campaigns. It was quite multi-cultural, I remember going to Bristol City games and Bristol Rovers games. I remember we walked out with Bristol Rovers players for a ‘Show Racism the Red Card’ campaign. People would be passing remarks about black players and black supporters. It would always be [abuse] aimed at the person because of the colour of their skin. ‘Go back to where you came from. You’re not welcome here.’ That sort of stuff.

“Football fans are probably the worst of them of all. When your team is going well, you’re the best in the world, but if your team isn’t playing well, they’ll find a way to get their frustrations out.

“With a player who is mixed race, the natural target would be the colour of their skin and where they’re from. You even see with Europeans in Ireland, ‘taking our own jobs’. It would be the same with black people and people that are of mixed race.”

And while there are evidently no shortage of ignorant people out there and the problem will never be completely eradicated, Jarrett is hopeful that positive changes are taking place.

“You’d be naive to think there’s no racism in Ireland, it’s far from that. It is more multi-cultural, but there are going to be that generation of people who are of that [racist] opinion. They will always use that, they’re so small minded. But kids don’t know any different, because they’re in schools where their friends are from different countries and backgrounds — they only see them as their friends. So as the generations get older, I do think Ireland will be a better place for it.

“You’ll always see comments on social media, be it Twitter or Instagram. Racism will never be gone. It’ll always be in our society. The biggest thing is trying to make sure that it is only the minority of people that are feeling that way.

People sit behind their screens and they’re free to say what they want and there’s no repercussions for it. It’s the same people who are always looking to insult others. They’re probably insulting their own people through different means. Then they look at someone different, not from Ireland, and the easiest thing to say is something about where they’re from or who their family are or what they look like.

“It is down to a lack of education I suppose and being so small minded to even come out with something like that — we’re all equal, what makes me better than you or vice versa.

“It’s just about putting that platform out there so that people aren’t afraid of it. We’d be naive if we were to try to not let people know about it, or try to cover it up. It is wrong and it shouldn’t be tolerated or accepted. But then it’s about how we go about it to try to limit that sort of thing.”

As a youngster, Jarrett drew inspiration from players such as Paul McGrath and Steven Reid, internationals who, like her, did not come from conventional Irish backgrounds.

Similarly, she hopes others can be inspired by her own career trajectory, and if she continues last season’s form, the accomplished attacker will surely be a key player for the Irish side for many years to come.

“It’s something that anyone who plays soccer or watches soccer as a kid, you always dreamed of. Growing up, playing soccer with the lads, we’d always play World Cup, little teams and pick your favourite player, who you’d want to be. I always wanted to play for Ireland. I remember I used to get a soccer jersey every year for my birthday. My birthday’s in July, obviously the Premier League jerseys would be out around then. I used to always get an Arsenal jersey and I actually found it the other day, I’ve an Ireland jersey from when I was 10 or 11. I got ‘Jarrett’ on the back.

“When I was 15, I played with the U17s and that was amazing — those four years playing U17s and U19s. When I played my first game for the senior team a few years back I got injured. So with the injuries, it’s been a bit hit and miss.

“But being called back into the senior squad in June, we played the double-header against Norway. So I was on the bench for the first game in Tallaght. I came on then away in Norway. It was just such a surreal feeling being back in it. Having my name on the back of an Ireland jersey and being in that environment.

The biggest one for me was we played Northern Ireland in our last World Cup qualifier in August. So for me, standing, listening to the national anthem, in front of the Irish crowd, my family were watching it in the stands and on the TV, and watching the president before the game… One of the cameramen got a picture of me shaking the president’s hand before the game and you can see the joy in my face.

“It’s something you can’t describe, playing for your country, especially with your family and friends watching you.”

Akpe-Moses, meanwhile, shares Jarrett’s pride in representing her country on the international stage.

“It is emotional, because you’re not only doing yourself proud, you’re doing everyone at home proud. People who supported you, your coach, your physiotherapist. When you accomplish something, it’s not just for you, it’s for everyone. Everyone feels the same way as you feel.

“And even getting selected [for Ireland], people are so proud of you. So the smallest things matter, not just to you, but to everyone else.”

Subscribe to our new podcast, The42 Rugby Weekly, here: