The build-up, the night before – I was really nervous. I don’t think I slept at all. I remember thinking, ‘I’ve got to sleep, I’ve got to sleep’ and then I didn’t. So the next day was a daze, really. Going through Cardiff and seeing all the people. Then seeing the size of the stadium. It was a whole experience and it went so quickly. It passed before you even knew it. Even the time on the pitch…I don’t really remember much of it.By that stage, it was already 2-0. I came on right midfield and I was up against John O’Shea who was playing left-back. I was a Man United fan growing up and Roy Keane was my favourite player. I grew up watching these players. This was the first time I had seen him in the flesh, right up close. I remember we had a throw-in and I was standing right next to him. And I looked at him and thought, ‘This is a bit mad’. I think I grabbed him or something and he gave me the stare and it frightened the life out of me. I just started smiling. It was just a surreal occasion.”

THERE WILL BE 116 games in the FA Cup today. In total, 232 sides will compete in the First Qualifying Round of the competition.

In Hertford, about an hour outside central London, the local side – who ply their trade in the Isthmian League North Division – will welcome Essex-based Grays Athletic.

Something different for Barry Cogan.

“It’s another new ground for me. I’ve been to Hertford but never played there. It’s a nice area but I don’t think the ground is meant to be the best. We watched a video of them the other night at training and the pitch doesn’t look great. So, I expect it to be a tough, typical, non-league battle.”

At this stage of his career, the 32-year-old midfielder will gladly take something different. For the bones of a decade, it’s been tough, uncompromising, unforgiving.

The raw and relentless ways of non-league football.

It’s a long way from Cardiff and the Millennium Stadium. A long way from facing Manchester United and getting stared down by Roy Keane. A long way from being a young kid and everything just rolling past in the blink of an eye.

Everything is slower these days. The legs are a bit heavier. He tries to influence games but it’s difficult.

“You definitely have to adapt,” he says.

“At a higher level, players are more on your wave-length. They make the runs. Sometimes you don’t even have to look. You play the ball and someone’s there. Now, if I do play that ball without looking, nine times out of ten players won’t make the run and you end up looking stupid. It’s harder for certain players at lower levels and it’s easier for others. If you’re a skilful player who can run past people it’s probably easier because the players aren’t as good. But if you’re a pass and move player, it’s probably harder.

It’s hard to influence a game because the turnover is so frequent. We give the ball away so much. Players don’t get their head up. They just put the head down and run with it because they’re really fast. It’s easier in some ways because you get more time on the ball but harder to influence in terms of getting the passing going. I don’t train as much now. It’s about getting through games because I’ve had a lot of injuries in the last few years – picked up a lot of hamstrings. I sit in midfield now and try and dictate the game as best as I can. It’s not easy with all these 21-year-olds who go to the gym every day and are flying around you. It’s not easy trying to chase them back. And people expect you to be better. When you’ve played at a decent level and you’ve come down the leagues people are like, ‘Oh, this guy is going to be fantastic’. But when you’ve lost a bit of pace and haven’t got the same players around you, it’s not as straightforward.”

This is his third stint with Grays but his first since 2009. A lot has happened in between.

In many ways he’s an itinerant, bouncing from place to place. After Millwall, he found it hard to settle. He found it hard to leave to begin with. But he had to. For his own good.

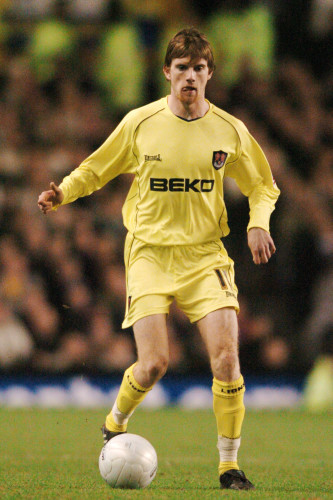

It seemed that he’d cracked it. 2004. Three substitute appearances under Dennis Wise and then the FA Cup final. The game was already beyond them when he was summoned to come on for his dazed and confused compatriot Robbie Ryan, who was suffering from a bad case of twisted blood after dealing with Cristiano Ronaldo for 70 minutes.

Cogan chuckles at the memory.

“He had a really hard time with Ronaldo but he didn’t do too badly, apart from a few of the clips you see of him getting rinsed,” he says.

“He came off shattered at the end. I think he was glad to come off at that stage.”

A native of Sligo, Cogan had been at the club for four years, having joined from Belvedere at 15. Now, with just 76 minutes of senior football under his belt, he slotted into the Millwall midfield on Cup final day.

“As much as Millwall went out there to try and compete, they also knew it was a day to enjoy,” he says.

“And by the time I came on the game was over. They (United) had control of it and there was never any doubt. It was more about going on, enjoying it and getting a couple of touches.”

Facing a side that had finished the Championship season in mid-table, United inevitably won at a canter. Van Nistelrooy added a third before the end and everything just blended together for Cogan. He was 19. It was a blur, a whirlwind.

There was a naivety, an innocence summed up by his interaction with Keane – his idol – at full-time.

“I went up and called him ‘Keano’ at the end,” Cogan says.

“I think he found that amusing. Some little, skinny Irish lad coming up to him and saying, ‘Alright, Keano?’ I didn’t know what else to say. I got John O’Shea’s shirt. And I still have that. You went around and shook everyone’s hand and you were in the players’ bar afterwards and saw all the big names. It was quite the occasion.”

Because United had already qualified for the following season’s Uefa Champions League, it meant Millwall would feature in the 2004/05 Uefa Cup.

Previously, the club’s European pedigree extended to two pitiful appearances in the Anglo-Italian Cup in 1992 and 1993 but that September, rather inexplicably, they welcomed Hungarian side Ferencvaros to The Den.

Cogan came off the bench in the first-half of the first-leg and they battled to a 1-1 draw. Two weeks later, he featured as a substitute once more as Millwall’s inexperience showed. In an intense, hostile atmosphere, they went down 3-1.

And then, it all changed.

“In football, everything happens really quickly,” Cogan explains.

“As much as you get into the first team and play in a Cup final, it can all turn just as easily the other way. I had done reasonably well but I got a stress fracture in my back which took a while to diagnose because I was just playing with the pain. I was struggling, trying to get through games and I wasn’t able to do extras or trying to better myself because I basically couldn’t even walk after finishing training. By the time it was diagnosed, it was another six more weeks trying to rest it and then you’re gradually trying to build it all up again. And you turn around and your season is gone, pretty much. And that was the season I needed to make a step up.

Dennis Wise left the club – he was the manager who fancied me and who gave me an opportunity. The following season, a manager came in who didn’t fancy me, thought I was maybe a bit lightweight and wanted to play a different style and I never really got a chance, to be honest. I could’ve done things differently. I probably could’ve got my head down more but it didn’t work after that. I played a few games here and there but never established myself.”

When Wise left as manager, Millwall went into free-fall. Just two years after being FA Cup finalists and just one season after playing in the Uefa Cup, they were preparing for life in League One. And Cogan was an after-thought.

“I think we went through four managers that season,” he says.

“The chairman left. It really went downhill. We got relegated from the Championship. It was a nothing season for me, personally. And I went away for a holiday at the end of the season and my agent phoned to say Millwall had got another new manager and that I wasn’t in his plans. I think we signed 17 new players in the off-season. Nigel Spackman came in and I don’t really know what was going in with the club, to be honest. I didn’t want to leave but I told my agent that if there was other interest I’d think about it. I talked to a few clubs but nothing really materialised and I had another year on my contract so I felt I’d give it a bit longer. I did really well in pre-season and thought I was in with a chance. Then, for the first few games of the season, I wasn’t even on the bench. And I thought to myself, ‘Right, I’ve just got to get out’.

The manager was alright with me leaving but I got called by the assistant manager telling me not to go. But when you’re young you don’t know what to think. So, I met up with Barnet. It was dropping down to League Two but I just wanted to play football. I was 21 or 22 at the time. It was probably a good decision – I played 46 games for them that year – but I look back on it and think I could’ve stayed at Millwall. Because Spackman lasted about six weeks and then his assistant – the same one who had asked me to stay – took over. So, you never know if things would’ve worked out.”

Cogan did a season with Barnet. Then, he left. He did a season with Gillingham. Then, he left. A season with Grays. You probably know the rest.

With so much relentless swapping and chopping, there’s a need to protect yourself in the lower leagues. Everyone is scrapping for themselves. There’s a massive turnover of personnel and a complete lack of stability.

It all feeds into one great, frenzied goldfish bowl.

“The further down the line you go, the more players there are,” Cogan says.

“There are so many footballers out there. When you go higher and get to that standard, it’s more difficult. But lots of people can play at lower levels. There’s a massive turnaround of players and a massive variant in wages. At Barnet, I would’ve been a high earner at the time. So, what they’re expecting – from their high earners – is someone they can sell on. They want other clubs to be interested in you or they’ll drop your wages. Even though I went there and had a good season, I didn’t do enough whereby clubs were coming in and were looking to sign me. So, they looked to cut my salary. I wasn’t going to take a wage cut to sign on again with them and Gillingham were interested and it was moving up to League One. I was quite excited to be moving up again but, the manager who signed me there – Ronnie Jepson – didn’t last very long and got sacked. And the next manager had different ideas.

The turnaround in players and managers is frightening. At that level, everyone is fighting for their own jobs. It’s very ruthless and so many different situations involved in it. So many things going on behind-the-scenes. But, if I was doing it on the pitch, it wouldn’t have mattered. That’s what it’s all about, really.”

In 2009, Cogan signed for Steve Evans’ Crawley Town and was enjoying his football again. But, overnight, the club picked up some new investors and had lots more money to spend. They brought in a wealth of new talent and Cogan was frozen out.

At 26, just entering his prime, he was a reserve at a non-league club.

He started to think about the future.

“It was difficult,” he admits.

“I was feeling the pressure a bit. It was short-term contracts I was signing. You’ve got a mortgage, things to pay for. It was a difficult time. And it’s difficult at that level anyway. In the lower leagues, you’re not earning enough to survive after football. So you need to start thinking about what comes next. You have to give yourself a timeline. Do you think you’re going to get back up the leagues? Your priorities change. You might start having kids. You start thinking twice about it. What do you want to do with your career? That was the way it went. When you drop down, you can’t give football as much time. And I never really settled after Millwall until I went semi-pro.

I just got married that summer and I had a think about what I wanted to do and where I wanted to go. I knew I wasn’t going to get back to a level where I’d be financially comfortable for the rest of my life. So, I needed to make a decision. I didn’t know what I wanted to do. When football is all you know, you come out of the environment and it’s really difficult. It’s like leaving school. You’ve got no qualifications. I fell into a few things. I did some coaching but I felt I needed to get away from football for a while. A friend got me a job in the London Underground and that was something I really enjoyed. And my father in-law has his own flooring company and asked if I wanted to get involved with him. And it made sense. It’s a family business, we get on really well. To be honest, I probably enjoy the part-time football more than I ever did full-time. It’s just a release. You don’t really think about football when you’re working. And when you’re playing football you enjoy it and don’t really think about work. It’s not that constant pressure about football all the time.”

In 2010, Cogan signed for semi-professional outfit Dover. He stayed there for five years – the longest stint he’d had anywhere since leaving Millwall.

And the buzz is still there, usually when the FA Cup throws up a juicy tie. In the last few seasons, he’s faced MK Dons, Huddersfield and Crystal Palace.

The distance he’s purposely put between himself and the game almost makes him enjoy it even more now.

“It’s something different. It becomes like every other job when there’s constant pressure on you to perform, to be training, to stay fit, do the right things, eat properly. You sacrifice a lot when you’re a footballer and when you’re down in the lower leagues, you’re not really getting the benefits from that sacrifice. You’re putting a lot in but you’re not really getting the rewards. When you’re working as well as playing football then the pressure isn’t as much. You’ve got something else to focus your mind on. Football is something on the side – a bit of extra money and it’s something you enjoy too. You still have pressure but it’s not as intense.”

There’s a well-worn romance to the FA Cup and its relationship with non-league clubs. Once a plucky upstart gets a plum draw in the Third Round, we hear about the magic of the competition. We delve into the archives and muse over the possibility of a giant-killing upset.

But, Cogan sees the other side of it all too often.

Just to get there, to even get a chance in the spotlight, takes arduous and exhausting effort. Today, he and Grays Athletic are a long way from prime-time on the BBC. Just like every other weekend.

“I haven’t got changed in my car too often,” he says.

“But you do go to some rough grounds. It is an experience, especially if you’ve played a bit higher up. But they take it so seriously, the non-league clubs. Sometimes you have to laugh at how seriously they do take it. But football is just so huge wherever you go in the country – no matter the level. They just want their clubs to do well. It’s the crowds, really. That’s the main thing. And there are some really good players in every league. Some really good footballers that go unnoticed. And it’s really hard to move back up the leagues unless you’re a goalscorer. I think it’s consistency that lets them down a lot – that bit of consistency.

It doesn’t get any easier. You still have to go out and put in a good shift on a Saturday to get a good result. When you don’t have the crowds it can be hard it get up for a game. Like, arriving at a crappy ground and there are 200 people there. Mentally, it’s quite hard to get yourself ready for the game. And if you’re not up for it you’re not going to play well.

I’ve always enjoyed the Cup and I’ve been lucky enough to play in some big games for various teams. I look forward to it, especially when the bigger teams come into the draw later on and you think you might get a decent round. Playing in proper games again. In the lower leagues, it’s difficult. You go to some hard grounds and the football may not be as good as what you’ve been used to. I’ve been right up to Barrow – right on the north-western coast – and then down to Truro in Cornwall. Some of the journeys…I remember going to Barrow one Tuesday night. It’s a six-hour journey. You get thumped 3-0 and then you travel all the way back again on the coach.”

With two kids, Cogan is stretched thin these days. Between his two jobs and his family commitments, it’s pretty hectic. But he’s hopeful of another cup run this season. Another shot. Another moment in the spotlight.

Subscribe to The42 podcasts here: