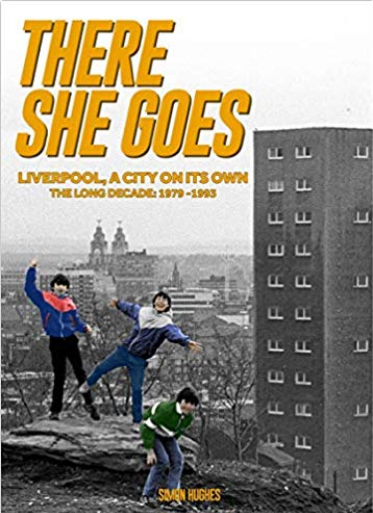

THE FOLLOWING PASSAGE is an extract from There She Goes: Liverpool, A City on its own, the Long Decade, 1979-1993 by Simon Hughes.

Before Kelvin MacKenzie became the Sun’s editor, its Sunday paper News of the World had been behind two thirds in the number of libel cases facing News International but since 1981, the figures had switched.

After Elton John successfully sued, MacKenzie’s brother Craig would leave the company and get another job – perhaps unsurprisingly, at the Express. MacKenzie, meanwhile, was broiling, shutting down any office discussions about the story which had led to hours of private meetings with Murdoch, who nevertheless kept him on and this only led to a sense of empowerment.

When Heysel happened, the Sun had gone further in its claims about the things Liverpool supporters had supposedly been up to earlier that day.

A group of looters had, apparently, stolen £150,000 worth of gems from a Brussels jewellery store.

Yet when claims like these are not backed up by proof, it means nobody is able to contest them. Perhaps MacKenzie remembered this after Hillsborough. How could the story be taken further? How could he avoid another embarrassment after the Elton John story?

The answer was in the place of Liverpool itself. While the slurs he would print were indemonstrable, libelling all of the Liverpool supporters present at Hillsborough, MacKenzie remained protected legally as nobody in particular was identified.

Some Liverpool supporters had, according to the Sun, ‘picked the pockets of victims’. Some had, according to the Sun, ‘urinated on brave cops’. Some had, according to the Sun, ‘beat up PC giving a kiss of life’.

Other newspapers would follow the Sun’s lead by repeating the allegations, but the Sun had gone first and no other paper had led with the headline which MacKenzie came up with: ‘THE TRUTH.’ Liverpool was at the centre of a war between two major tabloid newspapers in Britain.

The Liverpool Echo had quickly turned around a special 28-page issue and in leading with the headline ‘OUR DAY OF TEARS,’ had captured the feeling in the city without intruding on the excruciating details of a horrific event which had left family members not knowing whether their loved ones were missing, injured or dead.

The Sun, according to the McKenzie’s former colleague, sent ‘at least 25 reporters up to Liverpool’ in the 36 hours between Saturday night and Monday morning. ‘They had been told to get as much information by whatever means possible.’

Near Anfield, there are residents who can remember ‘local’ reporters knocking on doors, purporting to be from the Echo but speaking with southern accents. ‘At least three came to my house but when I asked them to show ID, they tried to change the flow of the conversation,’ one person said.

When the scale of the disaster was displayed in terrible detail through the development of photographs, the sense of competition between the tabloids intensified. On the pitch at Hillsborough, survivors can remember seeing some photographers turning over bodies with their feet so they could get clearer images.

Deborah Routledge, who was by the fence and being crushed to the point where she could only take ‘short gasping breaths’, could recall someone holding on to one of her ankles for two minutes before the grip became looser and the hand let go. She would appear on many the front pages in the days that followed because of the photographer working away in front of her.

‘I recalled thinking, “he’s going to take a photo of me and I’m going to die,”’ she told a courtroom thirty years later.

Before ‘THE TRUTH’ there was MacKenzie’s ‘GATES OF HELL’ splash which included a dozen pages with images of people either being crushed or receiving treatment.

The Sun wasn’t the only paper that day to use similar images — the Mirror, in fact, printed them in colour, not knowing as well whether any of the people turning blue in the crush had actually survived.

Initially, Liverpool’s fury was directed at the Mirror, with lines to the Radio Merseyside Roger Phillips phone-in jammed with complaints.

When MacKenzie was warned about printing the unfounded allegations against Liverpool supporters, according to his former colleague he initially replied in dismissive fashion, ‘Yeah, yeah…’ His instinct was to use the headline, ‘YOU SCUM,’ but then he changed his mind — ‘not something I’d ever seen him do’.

Inside the tabloid press it was commonly believed that once an editor had second thoughts a story was already slipping away from him, but those watching MacKenzie as the afternoon wore into the evening weren’t sure whether he was hesitating or concentrating.

As MacKenzie worked on the layout of the page, the subeditors seemed to vanish from the room. ‘We muttered amongst ourselves – it was clearly the wrong thing to do. But nobody had the guts – or the authority – to stand up to him.’

The story would begin like this: ‘Drunken Liverpool fans viciously attacked rescue workers as they tried to revive victims of the Hillsborough soccer disaster.’

The source had been the homophobic, apartheid supporting, death penalty advocate Irvine Patnick – a Conservative MP in Sheffield who five years later was knighted. Patnick said he he’d been supplied information by a ‘high-ranking police officer’.

This was a smear MacKenzie must have figured had no comebacks: Patnick was quoted repeating something he’d heard from someone who was never identified and the story was accusing nobody in particular.

When Liverpool City Council discussed whether it could sue the paper, it realised it could not. ‘Kelvin will have known there was no legal response to this, unlike some of the stories he’d been caught out on in the years before,’ the reporter at the Sun thought. ‘Because of this, I think he saw it as an opportunity to settle any lingering doubts about his judgement as well as his power.’

Despite the paper’s coverage of Heysel, there was no sense in the newsroom that MacKenzie had particularly strong negative feelings about Liverpool, though he certainly wasn’t knowledgeable about its history or dynamic.

MacKenzie would take a ‘no smoke without fire,’ attitude whenever Liverpool was in the news — believing anything negative as an absolute reflection of the way things were. He recognised Liverpool was a theme he could attack — readers were interested in the supposed scandal that came from the city.

‘It was my view that he [MacKenzie] had a subconscious view about the way things supposedly were in Liverpool and being the individualist, he saw the story as an opportunity he could exploit.’

MacKenzie, though, had underestimated the social networks that existed in Liverpool as well as the ferocity of reactions and the strength of resolve.

Liverpool’s football supporters were experienced and well-travelled, they understood how crowds flowed, what those authorities with a duty of care standardly needed to do to ensure safe passage — and the accusations that came Liverpool’s way rather than the direction of the authorities in the aftermath of Heysel heightened this appreciation.

By speaking to one another and absorbing the otherwise accurate and non-sensational reporting of what had happened at Hillsborough, the community of Liverpool quickly established a true course of events. The city would rid itself of Britain’s biggest tabloid newspaper.

Even though the Sun was printed in Kirkby, copies of the newspaper were spontaneously gathered from each newsagent across the town and piled high on a field in front of a council estate before being set alight — the first time newspapers had been burned on British streets since the 1930s when copies of the Daily Mail were torched in Jewish east London following a front-page endorsement of British fascist Oswald Mosley and his pro-Nazi Blackshirts.

Elsewhere across Merseyside, the paper was removed from the mess rooms in the manufacturing industries that remained and thrown in incinerators. Those seen carrying it on the street would have it snatched and ripped up in front of them.

While the Echo challenged the London papers and Sheffield’s police to ‘PRODUCE YOUR EVIDENCE’, Merseyside’s Police described the allegations made by the federation in South Yorkshire as ‘despicable’.

Before the Hillsborough disaster the Sun had sold on average around 120,000 copies a day on Merseyside but within a just a few days, that figure had dropped to just over 30,000.

‘We thought readers would drift back,’ admitted the newsman at the paper. He would speak about the paper as though it was a serpent. You might cut its head off but there was a confidence that it would recover and continue to grow.

Though suppliers continued to push shopkeepers to take the publication, fewer and fewer people were buying. Within a fortnight, 90 per-cent of copies on Merseyside remained unsold, meanwhile sales of the Mirror increased, which had raised more than £1million for the disaster fund by raising prices temporarily. The Sun was unrepentant in its claims about Hillsborough.

From inside the paper, though, MacKenzie was feeling the heat — ‘but only because sales had fallen through the floor, not because of the nature of the story’ — and this prompted him to call Kenny Dalglish, the Liverpool manager, asking him how he could improve relations. Dalglish recalled the conversation in his autobiography, telling him, ‘You know that big headline, “THE TRUTH?” All you have to do is put “WE LIED” in the same size.’

When MacKenzie said this was impossible, Dalglish replied, ‘I cannot help you then.’ The subsequent boycott would become one of the longest and most successful in history, costing Murdoch’s News International Empire hundreds of millions of pounds.

In 2019, it was selling less than 2,000 copies a day in the region. The struggle for justice was sustained by the boycott, helping campaigners believe they could achieve something. While MacKenzie — and many others — considered Liverpool to be ‘self-pity city’, the reality was quite the opposite because few were feeling sorry for themselves. They were actually trying to do something about it and would not go away despite all of the horrendous emotional setbacks.

In 2016, when the inquests about what happened at Hillsborough were finally heard, delivering a verdict of unlawful killing, MacKenzie finally apologised for his role in the reporting but even then, he implied that he, somehow, too was a victim: ‘I feel desperate for the families and the people and I also feel that in some strange way I got caught up in it.’

12 months later, he would leave the paper once and for all after comparing Ross Barkley, a Liverpool-born footballer with Nigerian grandfather, to a gorilla. Back in Wapping, the one-time reporter at the Sun considered his own role in the aftermath of Hillsborough. Could he have done more to stop MacKenzie?

‘Not really,’ he said flatly. ‘Everyone was too busy looking after themselves.’ ‘We were all hoping we would have some sort of closure today and we haven’t,’ said Margaret Aspinall on the steps of Preston Crown court almost 30 years to the day since her son James was crushed to death at Hillsborough.

It was April 2019 and there had been no verdict in the trial of police match commander David Duckenfield who was accused of gross negligence, causing the deaths of 95 people. It had taken the court clerk five minutes to read the names of the deceased at the start of the trial three months earlier.

Duckenfield’s ‘extraordinarily bad’ failures, according to the prosecution amounted to manslaughter after he failed to try and ‘avert tragedy’ after Gate C in the Leppings Lane end of the ground was opened.

Duckenfield was charged with only 95 deaths because the 96th victim, Tony Bland, died four years later. Laws in 1989 said no crime causing death could be charged if the victim died more than a year and a day later, though that law was abolished in 1996.

There was ‘no evidence the police were notified or consulted’ of the layout changes at Leppings Lane that had taken place in 1988 which meant 10,100 people a year later had just seven turnstiles to enter the ground.

The prosecution outlined the crown’s case: ‘the risk of death was obvious, serious and present throughout the failings of David Duckenfield to show reasonable care in discharging his duty as match commander.’ He had not monitored the ‘desperate situation’ outside the turnstiles and did not take action to relieve the pressure, including the option of delaying the kick off.

One of his officers, Robert Purdy, admitted: ‘Something had gone wrong in terms of policing the approach to…Leppings Lane’ and the crowd should have been stopped further up the road.

The pressure of the people in this ‘bottleneck’ was so severe that the securing spike for a large metal gate outside bent and the gates ‘sprang open under the pressure,’ though at that point a South Yorkshire police officer incorrectly said on police radio that Liverpool supporters had ‘broken the gate down.’

Purdy believed the overcrowding at the Leppings Lane turnstiles remained so severe that ‘people would die if the situation was not relieved’ and this led to the opening of the exit at Gate C at which point Duckenfield ‘failed to take any action himself…to prevent crushing to persons in pens three and four by the inevitable flow of spectators through the central tunnel.’

The prosecution: ‘Duckenfield’s failures continued, each was compounded by successive failures, each was contributed to by earlier failures; each…flowed from his own personal decision making and fell squarely within his persona; responsibility as match commander.’

85 of the 96 people who died at Hillsborough were in pen three and 23 of them had come through Gate C when it was opened. Duckenfield had given evidence in the inquests between 2014 and 2016 where he accepted some of his failings were ‘grave and serious’ and that his ‘most serious failure’ was not closing the tunnel before ordering Gate C to be opened.

In conclusion, the prosecution said: ‘Ultimately [Duckenfield] failed in the most appalling manner to monitor what was happening in pens three and four and to…prevent…the…crushing the life out of so many people.’

While Duckenfield’s defence case lasted just 74 minutes and consisted of read evidence from his deputy on the day, Bernard Murray, the jury deliberated for longer than 29 hours but was unable to agree whether the match commander was guilty or not guilty of manslaughter by gross negligence.

Steven Kelly, whose brother Michael died at Hillsborough, did not want to see a retrial after 11 weeks he did not want to ‘go through again.’ Barry Devonside, whose son Christopher was one of the victims, felt differently. He wanted a conclusion: ‘an end so we can return, as a family, to some sort of normality.’

*In June 2019, it was announced David Duckenfield would appear again at Preston Crown Court. His retrial started in October 2019, three decades and five months after the worst stadium disaster in the history of British football. He was subsequently cleared over the deaths of 95 Liverpool fans.

There She Goes by Simon Hughes is published by deCoubertin Books. More info here.

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!