Updated at 07.54

THE SECRET FOOTBALLER is an anonymous former Premier League footballer, now retired, who first came to prominence following the success of a regular column with The Guardian.

He has since written a number of acclaimed books including The Secret Footballer’s Guide to the Modern Game and The Secret Footballer: Access All Areas.

His latest offering, HOW TO WIN: Lessons from the Premier League sees him collaborate for the first time with The Secret Psychologist in a book that delves into the psychology of virtually every aspect of modern football from a player’s perspective.

In this entertaining and insightful book, the author explores a series of topics, such as: ‘What separates the good from the truly great players? How do football managers get the best out of their team? How do you come back from a crushing defeat to win?’

The42 recently interviewed the Secret Footballer about some of the subjects explored in his new book.

What prompted you to write the book?

I was researching the game as I tend to do by visiting clubs and talking to managers mainly, rather than players this time. And it really became apparent that managers were becoming more than coaches in the modern game. Very often they were mediating or trouble shooting or solving problems thrown at them by the game and mostly, by their players.

They’re more like chief negotiators in a hostage situation these days. But, broadly speaking, all of these issues and mind games fell under the same banner: Psychology. So I just came up with a very simple question that I asked all of the Premier League managers, ‘roughly what percentage of your job is about psychology?’

And they came back with their answers… 70%, 80%, 90%… it was a big eye opener. And then one day I was walking through a train station and stopped in WH Smiths. I was looking at the book charts when I noticed a common theme. Out of the top 30 there were 18 books that were about, or based on, psychology… how to make yourself do this or that… how to be better at work etc… three were in the top five, including the number one.

And so I thought that if I applied the Secret Footballer and How to Win in The Premier League to psychology, I think I’d have a really interesting and eye-opening book. Hopefully that’s come across in the final book.

Your wife writes in the intro of the book that you hate talking to people as an ex-footballer because you often fear you’re being recorded. This must be a very exhausting and intense way of living?

Do you know something. My paranoia is bad. It’s a result of depression and anxiety. I’ve always had it. And I have to be honest and say that while I’m obviously not the England manager, my paranoia is not helped by newspapers constantly trying to stitch football people up to create a bit of cheap news by covertly recording them in hotel bars.

They managed to bring the England manager down, and for what? Was it really a hanging offence what Sam Allardyce said? I wake up in a cold sweat when I think about some of the conversations that I’ve been involved in and continue to be a party to as a person that played football and who people might want to record.

You’re right, it is draining. It’s almost as draining to read about the non-stories the next day on the back of the papers.

Why do many British people dislike winners such as Andy Murray and Lewis Hamilton in your opinion?

I think it’s in our recent DNA. I think that we were a nation in the previous 400 years before the turn of 1900 that had things largely our own way. I think the two world wars, while we were ultimately triumphant, were a reality check.

The world had caught up, they weren’t afraid of us and they still aren’t. I think that we realise that we are a small island capable of only so much. We don’t tend to poke the Cobra anymore because we’ve lost our anti-venom. That tends to feed in to our conscious as individuals; ‘I’ll give it a go and hope for the best but I’m only human…’

And I think that when you look at countries where that power now resides, you will find the confidence that we once had. America is the obvious example, the money, the power, the resources and ultimately the confidence is at their disposal.

When we look at Andy Murray and Lewis Hamilton, we see people who had the confidence that we would like to have and so we perhaps have a bit of jealousy there.

And also we look at them and because of our history, we now understand that we can be beaten. I think we look at these guys and girls now and think, ‘don’t be too sure of yourself, you’re heading for a fall’.

It’s going to take us time to get our confidence back as a nation I think. To be honest, the reasons are so broad that I could probably write a book on it. This question is probably a good indication of why Twitter works so well. There is absolutely no subject in the world that can be summed up in 140 characters so succinctly that people can’t rip you to fucking shreds.

Do you think you’ll be a manager some day and are you in anyway confident that you can succeed as one? And if so, what makes you believe you can thrive when so many others have failed?

I flutter between it, to be honest. Some days I really feel like I should give it a go because I have certain traits that would work well and that I will regret it when the opportunity is no longer there… and other days I have completely the opposite view.

Where I really see myself is at board level, helping to run a football club on a day-to-day basis. That’s where my real strengths lie.

You portray yourself as different from the average footballer. What makes you different, do you think?

I think one of the first lines that I ever wrote at the Secret Footballer is, ‘I am not whiter than white’. So I’m not saying that I’m completely different. I have plenty of shortcomings.

Where I am different is that I’m a lot more perceptive, not because I’m good at it but because I choose to be that way because I was unsure of the football world when I came into it.

I didn’t want to make an idiot of myself by making a silly mistake so I studied everything. Only when I fell into that way of thinking did I realise that I was different. The other players didn’t overly care; not many of them anyway. So I suppose that I’m now versed in that way of thinking and I apply it to most things in my life as a matter of principle.

You write about growing up and how your school was invariably better than the ‘posh’ school at various sports. Why do you think top-class footballers nearly always come from working-class backgrounds? Is it mainly down to their greater hunger to succeed, or is it more complex than that?

Well you can spin it on its head and say that they would have beaten us at polo. We were probably eating any horses that we had for burgers in the school canteen.

There is hunger to succeed among kids from all walks of life. The kids that go to my son’s school are keen to be brokers and captains of industry and Tory politicians. I don’t know why.

I don’t know why I wanted to be a footballer other than I felt like I was happy when I played it. Maybe these kids think they’ll be happy if they fall in to some of the jobs that I’ve mentioned. Or maybe it’s about pleasing their fathers.

I suspect there is more expectation to succeed and the resources to ensure success at the top of the social divide, rather than the bottom.

You write a lot about footballers’ psyche. Were you mentally strong in comparison to the average footballer, do you think?

I learned to be mentally strong. I was very lucky in that my first manager was ruthlessly tough on me. He and an ageing foreign goalkeeper at the same club taught me to win.

They taught me what it means to be a winner. When you buy into the fact that winning is the be all and end all of everything in your life, then it is quite astonishing what can be achieved.

By the time I moved to a bigger club I was ready to drag everybody on my own journey to the top. The other players fed off my enthusiasm for winning and being as professional as possible.

I could be overwhelming with my appetite to win sometimes and many of the players didn’t like me for having no life outside of football and winning. We would argue a lot, but I’ll tell you something — every single one of them respected me and knew that when the shit hit the fan on the pitch, I was somebody that they could rely on.

I was never interested in making friends in football, I used to tell the other players that. They’d laugh at me, they didn’t get me, but they’re also all millionaires off the back of following me.

On a similar note, would it be fair to say that footballers, in general, are much mentally stronger than the average person and have an extraordinary capacity to deal with pressure? Is that a key trait for making it in the game?

Not all footballers. I’ve seen some real babies playing football, even in the Premier League. Lots of players that can’t handle the aggression, can’t handle the crowd, can’t handle the day-to-day mundaneness of the whole thing.

And it is mundane outside of playing the games, believe me. That takes a certain level of mental toughness too. Boredom is a killer. It’s been proven.

But I think that if you look at guys that are seriously talented like Ronaldo… Mental toughness is a huge part of your game. Psychology is hugely important.

Ronaldo goes to every ground knowing that people want him to lose, have as bad a game as possible and ultimately fail. And yet he delivers.

I’ve seen players wilt in stadiums where only a few people in the crowd are giving them some shit in stadiums a sixth of the size.

That said, the vast majority are tough cookies mentally. On the pitch at least. The interesting thing is when that mental toughness covers up for the failings in their football technique. It’s amazing how far that has carried some players!

You write about players using creatine, which is obviously legal to use, but do you think there’s an issue in football with illegal (or indeed, legal) performance-enhancing drugs. Did you ever come across it in your experience of playing the game and do you believe it’s naive to assume football doesn’t have the kind of problems that other sports, most notably cycling and athletics, have suffered from in recent times?

I think that recreational drugs in the summer are rife. Cocaine is rife in the summer. Ecstasy is common too. But in season, recreational drugs are pretty much — although there are one or two rare exceptions — non-existent.

It just isn’t worth the risk, there is so much to lose and everybody knows the rules and the implications. And I don’t think many players miss recreational drugs, because they never took them in the years before they became footballers.

The vast majority of us, while not being a fully fledged professional until we’ve signed that first contract, have acted as professionals since we were 10 years old. So recreational drugs don’t often cross our paths. It’s the exposure to recreational drugs at an early age that is dangerous, but footballers tend to sidestep those pitfalls.

The concern is if so-called doping doctors infiltrate our game. There is already a ban in this country on blood spinning to increase white-blood cell count and speed up injury healing, but it’s legal in Germany. So we all travel to Germany and come back again.

Morally, you may argue that that is wrong, but then you would be biased towards the fact that we consider it illegal rather than contemplating the fact that it is legal elsewhere, and not in the back of beyond, but in a first world footballing hotbed.

Are we getting to the point where top footballers have earned so much money that most of them will start to feel they don’t need the stress of being a manager and do you agree with Alex Ferguson’s suggestion, which you reference in the book, that football management is now largely about being a good psychologist?

I think I answered this already. Also, Sir Alex really can’t walk on water by the way… “Wayne Rooney would play football for free because it’s in his blood…?” Fuck off.

Do you think the problems in English football you discuss in the book (in relation to the development of young players etc) will be rectified anytime soon and that England will eventually win a major tournament?

No. There is too much money in our game. Too many people with their hands out that don’t have to try. There are no mavericks like Cruyff or Guardiola revolutionising football.

Wenger could have been our saviour but he was able to recruit kids to play the right type of football from all over the world. If only he’d arrived 40 years ago when the league was still largely English, we could, genuinely, have been world champions.

It doesn’t sound like a lot but guys like Cruyff and Guardiola revolutionised not just their own clubs but the landscape of world football. Arguably, we have never had that.

Even Sir Alex Ferguson, who was obviously successful, never laid down a template that we could all follow from the ground up. He largely relied on having the best players and the biggest budget that extended to his scouting network.

He had the perfect storm, but where is the legacy on the way British football is played today? There isn’t one. Not even at Manchester United. That’s the problem with our football.

How big an impact can a sports psychologist have on an individual player or team in your opinion? Can they drastically improve him/it in certain instances?

It is a misnomer that you have to drastically improve a professional football player. If you have to start drastically improving players then, by definition, you have signed the wrong players.

Clubs sign capable professional footballers that occasionally need tweaking and realigning. You don’t take somebody like Usain Bolt and say, ‘right, we’re going to try to break 9 seconds’. That’s not the goal.

The goal is to be the best you can be within what you are realistically capable of achieving. But proportionate to what is required of players and what is sometimes delivered on the pitch, psychologists can have a noticeable baring on performance.

But we are not looking for 50% gains. That is unachievable. We are looking for an extra 2%-5% because that is a massive gain. And if you scale that up and apply exponential growth — that is to say, growth across all 11 players in one match — then those gains are enormous.

I am a big believer in individual growth and as a result, exponential growth, because I have seen it with my own eyes. A club I once played for put in place a programme to extract marginal gains from each member of a squad and it was a spectacular success.

I tell you exactly how they did it in the book and it is nothing that you can’t recreate in your own life no matter what job you have or what you want to achieve. And unlike me, they charged £150,000 for the answer!

You write about moving to the wrong club. What are the key questions a footballer must ask himself when faced with a potential move and what can they learn from your mistake?

I had mitigating circumstances, which meant whichever club I moved to was going to be tough. I had a newborn baby and I moved my wife away from her entire support network.

Secondly, I was banned from driving so we were stuck in the house with a screaming kid.

Thirdly, I was played out of position and although I felt I did okay, I was not doing what the fans thought I was going to do, which made it tough to win them over.

Fourth, the style of the football was horrific and I knew nothing about it before I signed.

In hindsight, I should have made enquiries with fellow pros that knew what the manager was like and what the style of the football was like. My fault, nobody else’s. Do your research. You may make more money, but you may have to sell your soul in the process.

You recall talk of a potential England call-up at one stage in your career, and you essentially suggested at the time that you weren’t good enough for international football and go on to explain that your club stopped the interview, in which you said this, from being published. Do you feel like football has become too sanitised in recent times? Should players and pundits be encouraged to be more honest, or is the current environment inevitable and impossible to change?

I made those comments as a protest at the FA and the way England was run at that time. It was rudderless and ridiculous. I was a Championship player and I did the interview only to highlight the dearth of talent at the top.

I was a very good footballer but ultimately a Championship footballer at that time. I wanted to draw attention to the fact that none of the top Premier League teams were producing anything like the number of homegrown players that they should have been.

Ultimately, my club side saw it as a naive interview that devalued my transfer fee.

Obviously, if I had been called up for England at that moment then my transfer value would have rocketed. But don’t forget too that I would have been knocking on doors asking for more money too.

So they suppressed the article. I can see their point, business is business. But you ask me why England never moves on? The fact that everybody has their hands out and never raises their head above the parapet? Look no further…

Tell us about the psychology of home versus away matches. Burnley this season are a good example of how the two scenarios can be considerably different. Did you generally feel significantly more confident prior to home matches when you were a footballer?

When I played for a team that could beat anybody it faced, I always felt more confident at home, because you could visibly see the opposition wilt in the tunnel. The louder they were, the more scared they were.

And psychologically, nobody expected them to win, so they really did turn up and hope to get beat by an odd goal. But they expected to lose, that’s the point. It’s all in the head.

When we would travel to those same teams in the reverse fixture, we would try even harder, because we knew that that was the making of a great team. And we wanted to be a great team.

It’s not about getting used to the pitch or the area or the changing rooms or anything else like that… It’s about what goes on in your head and how well you deal with the way a team plays at home.

Very often, the home team will have a real go at the opposition for 15 minutes off the back of the adrenaline tumbling down the stands from the crowd. If you can deal with that, then you have more than half a chance.

What can a professional athlete or aspiring professional athlete take from reading this book?

Something that myself and The Secret Psychologist were very keen for when writing this book was to make sure that the tips and tricks for being a professional footballer ultimately translate to those people that are not professional footballers. That’s why we called it How To Win.

Football is a microcosm, a world where everything that happens to most people in their lives happens to us in a matter of a few years. And during that time, we have to learn how to be ruthless bastards, so that we can be as successful as possible, because we know that our career is finite.

The lessons that we learn can be implemented in any walk of life. I am a big fan of psychological experiments and I am endlessly fascinated with how I can apply the lessons to my life. But you don’t have to be a footballer to do that. Anybody can do that.

Whatever job you have or whatever you want to improve or achieve in your life is there for the taking provided you know how to get there. How To Win can help with that.

It’s a ruthless self-help book in many ways. It has to be that way because the guys implementing the psychology only have a very short window to work with the players before they move to a different club or retire. This is what makes the mix of psychology and football so fascinating for a lot of people.

You write very honestly about retirement and all its pros and cons. What do you miss most and what do you miss least about playing?

Well, I suppose everybody likes their ego stroked and when you finish playing football that stops. So you can go back to where you were a hero and carry on, or you can move on.

While I understand that we can’t all move on to new interests, I personally find it extremely sad when I see old pros wandering around the halls of the stadiums that they used to grace in their prime. I never wanted that for me.

I don’t go to any of my old clubs, I am all but a recluse. I refuse to do interviews and meet and greets and lounge presentations for sponsors. And I’ve been offered a lot of money for private appearances. I just won’t do it.

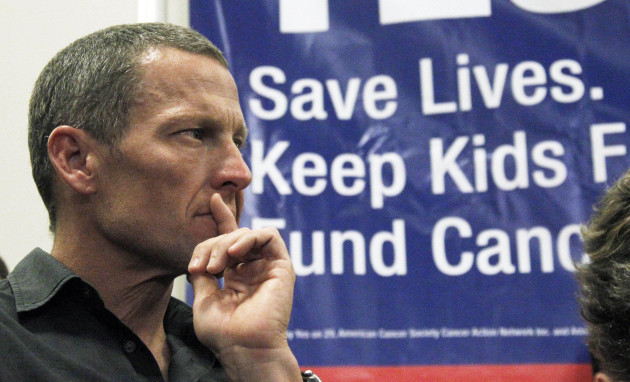

I keep a quote in my head that my great friend, the Sunday Times Chief Sports Writer, David Walsh, once said to me after he’d pursued Lance Armstrong for 13 years to prove that Lance had been doping.

I had asked him why Lance came back in to racing after seven Tour De France victories, why couldn’t he just retire, he’d had got away with it most likely. David said… “Lance came back because he couldn’t stay away. Why couldn’t he stay away? Because it’s like the oldest theme in Hollywood that you’ve ever come across, the bank robber, the assassin and the jewell thief. They do their jobs brilliantly, they win every time, they get all the money they should get, they kill all the people they should kill, they get all the diamonds they should get…. but somebody comes to them and says.. ‘one more job!’ And they can’t resist. Because that was them living like they had never lived before… and would never live again.”

As soon as David said that to me, I knew I would never go back. It’s one of the saddest indictments on professional sportspeople that you will ever read. And the truest.

HOW TO WIN: Lessons from the Premier League by The Secret Footballer and The Secret Psychologist is published by Guardian Faber Publishing. More info here.

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!