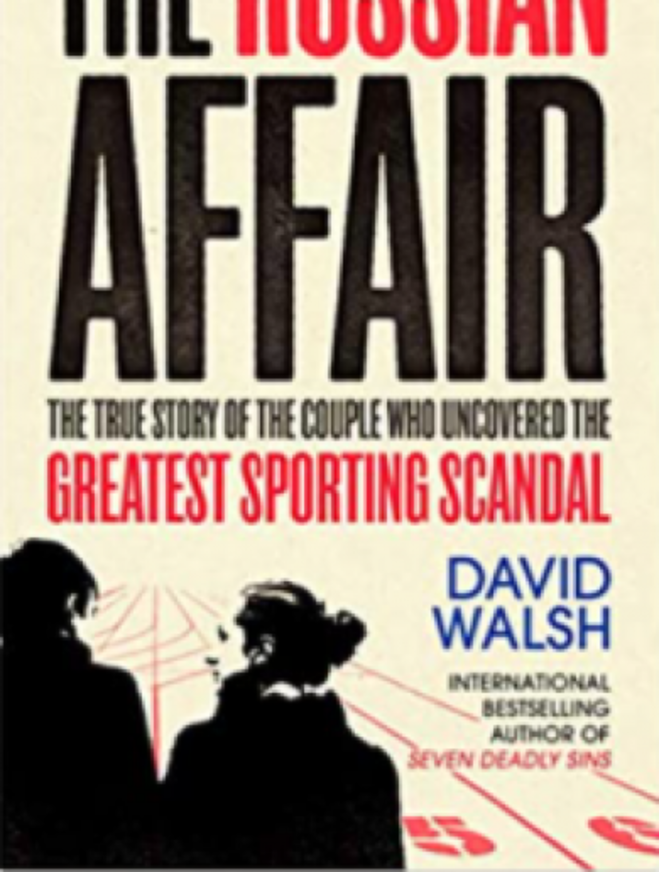

THE FOLLOWING PASSAGE is an extract from The Russian Affair by David Walsh.

Sometimes when she was still young and they were back in Kursk, Yuliya would ask her father why he lived as he did. She remembered his honey bees and his high hopes. Now he had his alcohol and nothing else.

‘Why do you live like this, Papa?’

‘Live like this? Me? Well, your mother is not easy. She raises a stink every day. You know what I mean by raise a stink? I work hard all day and then your mother is another day’s work.’

Yuliya had hoped for more. She said nothing.

In the first few years of the new Russia, if your boat had been lifted on the tide you were given the chance to forget. You forgot the old Russia with its damp grey queues. You forgot those black jokes.

‘What is 200 feet long and eats vegetables?’

‘A queue for meat in Leningrad.’

‘Knock-knock.’

‘Who’s there?’

‘Your neighbour from downstairs. Get out, get out quick. The whole building is on fire.’

‘Thank God. We thought it was the police.’

The Rusanovs couldn’t forget. When Russia opened the sluices to western money, barely a dribble reached Kursk. Men still drank cheap liquor in streets and parks. People fought and people killed each other. The police never came for fighting. For a murder sometimes they showed up. Moscow with its oligarchs, swish foreigners and coffee franchises was another country. The Rusanovs lived in the cheapest part of a cheap city.

Kursk’s history was about endurance. Endurance was affordable but, like the cheap alcohol, it rotted you from the inside. Lyubov and Igor endured together. They worked in the same factory, making car tyres in bad light. The smell of rubber clung to them and they came to hate the factory, just as they grew to hate each other.

As Igor saw it, ‘why do you live like this?’ was a dumb question for Yuliya to ask him. The question was how? ‘How do you live like this, Papa?’ He didn’t know the answer to that.

Grandpa Mikhail had retired from his life as a small farmer but he kept pigs to be killed and occasionally a calf nursed from birth would be brought to town for somebody else to buy and to slaughter. The proceeds went into Lyubov’s purse, Grandpa’s way of helping his daughter and his grandchildren. Yuliya never mourned those skinny, docile cows. Their slaughter brought money. When a cow had been traded Yuliya would ask her mother if she might buy her some clothes.

‘I have no money,’ Lyubov would say. Nothing more, but Yuliya knew she was lying. Eventually Yuliya figured it out. Lyubov kept it all under the bed, accumulating slowly. The more the pile of money grew, the more Yuliya resented her mother. Why save for a rainy day when you are already drowning?

Her father, meanwhile, grew more problematic. After work he would meet with friends. They bought alcohol in stores and sat in the park and drank. A confederacy of sour drunks.

Sometimes they drank vodka. More often they drank samogon, the cheap moonshine that was the drink of choice for the poor. Samogon was made by your friends or friends of your friends.

It was dirt cheap and it made you mad. In some places it out-sold vodka by five to one despite being the bottled version of Russian roulette. Anything from dimedrol to methanol might be added for effect. You never knew what you were drinking, just that you were getting drunk. Igor liked samogon, maybe even needed it.

Yuliya’s earliest memory of her dad’s drinking was from a night in the little fourth-floor apartment in Kursk. She was almost asleep. Her mother had been home from work for a few hours. Igor arrived home from the park. He was noisy and it was already late. She knew by the sounds he made that he was drunk but she closed her eyes and tried to sleep. They were fighting, though. She could hear all the shouting and then her mother crying and then an ambulance came. Yuliya was eight years old and crying and standing in pyjamas. Igor had taken a heavy box and hit her mother in the head with it.

For as long as Yuliya could remember, Uncle Anatoly never spoke to his sister Lyubov. That was a fact of life and there were bigger things for an eight-year-old girl to worry about. Now she recalled her mother telling her that her father had once come home from the factory drunk as usual. His mood was unusually foul and when he set about attacking Lyubov, Grandma Nadia had tried to protect her daughter. Igor had pushed her violently and Nadia had fallen hard onto an old bicycle that leaned against a wall. A pedal or a handlebar – nobody was ever too sure which – punched hard into her side. The hospital said that the damage was to her liver, and X-rays showed an ominously large and dark spot on the organ. Some months later Nadia died from liver failure. She was in her mid-fifties. Cancer of the liver was the official cause of death, but Uncle Anatoly had always believed that Igor had killed his mother.

From that night when the ambulance had come, Yuliya knew no peace. The curtain came down on her childhood. Her father drank more and he drank worse. If Lyubov wasn’t there when he came home, he picked on his daughters. If Lyubov was there, the little girls ran to protect her and absorbed the brunt of his anger.

‘My sisters and I, every time we tried to save our mum,’ Yuliya says to Vitaly, holding on to the part she can bear to remember. Not that she wasn’t scared of her dad. When he came for her it was like war. She grew used to it and if anything she grew more defiant, but long after he was gone the bad dreams lingered. The end, when it arrived, didn’t come in their apartment in Kursk but in the little village where she had enjoyed her happiest times.

Yuliya told Vitaly things that, to her, were run-of-the-mill stuff, scenes of everyday life in her corner of Kursk. No drama, no casting herself as victim, no plea for sympathy. This is how it was, and it wasn’t all bad.

When she was 17, she’d discovered running and begun training in athletics. Nothing very serious but she discovered after a stretch of training that she was improving, that she could run faster. She liked that. It encouraged her to believe that a life beyond Kursk was possible. She wanted to run like a professional. Professional athletes made money and didn’t live in Kursk. She didn’t know where precisely they lived – Moscow probably – but she decided to train every day regardless. By now she had accepted that her father would never again be that happy man with his jar full of honey. When marinating in samogon, his seed turned bad.

In the lengthening days of spring and the long days of summer, her father would order her to the village to work in the fields. She said that she couldn’t and she wouldn’t because she had to train. His hatred for her grew every time she defied him. She gave the hatred right back to him. Toe to toe, eye to eye. From defiance she drew strength, and the stronger she grew the better she ran. Keep it coming, she thought, keep it coming. She was in training camp when it happened.

Igor went to the village alone and fell into drinking with Grandpa Mikhail. Both men were alcoholics but Grandpa Mikhail was an easy and lovable drunk. Nobody ever knew the details of what exactly occurred but in the morning Lyubov phoned Yuliya at training camp and told her that she needed to come home. Grandpa Mikhail was dead. Igor had beaten Grandpa to death with the stout stick that the old man used for mashing pig feed.

Yuliya was happy when her father went to prison. He would never come home to them again. There would be no more wars. He sat in prison for seven years and they had a rest from him. Lyubov divorced him without any trouble. Her sisters visited their father in prison from time to time but Yuliya never went. She never wrote and she never asked about him. Maybe it was different for Katia and Gelia. She didn’t spend much time wondering about why they went to see him. At night she still had the nightmares about him. So did Lyubov. That was their inheritance.

She kept running obsessively.

Vitaly was excited to see that she loved to run. He smiled to himself and allowed a playful thought to linger: Mr and Mrs Forrest Gump! But he knew that she saw things not quite as he did.

Some people, seldom Russians, spoke mystically about the sensation of running, the endorphins, the clear-headedness, the energy, the feathery lightness, the chi of it. For Yuliya it was simpler: running was a ticket to a better life. She understood clearly that she could make money on a track. Her family never had money and knew nobody who could get her onto the ladder that would lead to a good job. Yuliya would have to make her

own way. If the speed at which she ran could help to pay for better things then she would do whatever it took to get faster.

The 800 metres was a race of maximum pain. Two laps, flat out. When the body wept with pain there was still 250 metres left to run. It wasn’t a case of who could inflict the most pain but who could endure the most. She was good with that deal. Your legs hurt? Your chest hurts? That’s not real pain. She had Kursk in her being. She could endure more than most.

When Igor died she surprised herself. For a while, she wept every day. She would remember her dad in the fields. And she would recall the two occasions that she went to meet him after he got out of prison. Once they had sat across a table from each other, talking awkwardly as they ate. She hadn’t been sure who this person was or if she had anything left to offer to him. He had been pale and a little fatter than she remembered him but better in himself than before. Calmer. Drinking just a little, he had said. She’d told him that if he started drinking again she would not have a father. Never. And if he started a new life and tried to be a good man she might have a father and she would talk to him. He had been quiet. He’d had nothing to say. No promises to make. That was all.

When he was in prison Igor had stopped smoking because blood came up when he coughed and he was afraid of dying in prison. Free again, he had gone back to tobacco. He died from lung cancer at 52. As much as her life would change, Yuliya’s memories stayed with her. Grandpa Mikhail waiting for her, being happy to see her. The good times before it all went wrong.

Vitaly listened to her story, soaking it up. This small, beautiful woman and her fucked-up, broken life. She was more moonlight than sunlight.

And she doped.

And there was still a question he needed to ask.

The Russian Affair by David Walsh is published by Simon & Schuster UK. More info here.