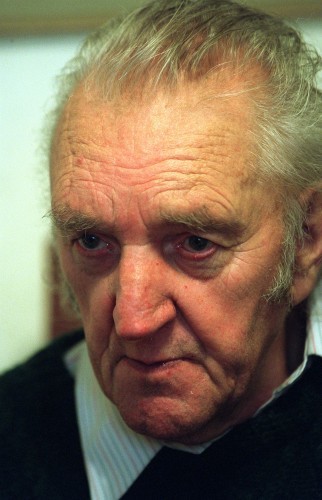

THE LEGENDARY LATE sportswriter Con Houlihan compared him to ‘Jesus Christ,’ commentators would often use terms like ‘warrior’ and ‘gladiator’ to describe the man, and to Sligo Rovers fans, he will be remembered as one of the greatest players in the club’s history.

“I don’t know why you’re talking to me,” he tells The42, arguing that better players than him have graced the League of Ireland.

While that might be true, not many people in Irish football are as beloved by any club’s fanbase as Tony Fagan, or ‘Fago,’ as he is perennially known.

A few years back, RTÉ asked fans to nominate a club legend, with Fagan winning the Sligo vote comfortably.

Occasionally, a player comes along who ultimately epitomises the spirit of a particular team. For Liverpool, in recent years, it was Steven Gerrard. For Roma, it was Francesco Totti. For Juventus, it remains Gianluigi Buffon. And while Fagan may not have had the exceptional talent of these other players, he certainly had a similar level of passion, loyalty and dedication to the cause.

Fagan, who turns 70 in January, loves Sligo Rovers as much as a person can love a football club. For most of his life, he has lived just 100 yards away from their stadium, the Showgrounds. As a youngster, he dreamed of representing them. He went on to fulfil this ambition, helping the team win the league title for the first time in 40 years during the 1976-77 campaign, in addition to a first-ever FAI Cup triumph in 1983. The former star had a stint coaching Sligo’s reserves later on in his life, and to this day, he continues to attend every home game. In October 2016, he was inducted into the club’s Hall of Fame, having made a record 590 appearances and scored 47 goals in 20 years playing for the club.

At the end of the interview, he says to drop him a line if I’m ever in the Showgrounds.

You just mention Tony Fagan, people will say ‘that’s him there,’” he adds. “‘That old buck, that’s him.’”

Yet despite all he achieved, Fagan points out that it “wasn’t all rosy” over the course of career, elaborating on issues we will get to later.

1. Starting out

It might have been different though, had he elected to take an alternative sporting route. As a youngster, he was good enough to represent Sligo at minor level in GAA and started playing soccer for St Joseph’s in the street leagues. He subsequently spent two years with the Boys Club, and after impressing at youth level, in 1967, the 17-year-old joined Sligo Rovers. Before long, he was playing in the first team, operating as an inside right before gradually developing into a central midfielder of great renown.

“I used always go on a Sunday to the match,” Fagan says of his childhood. “What I thought I’d see was good football and y’always say: ‘Some day, I’d like to be out there on the pitch playing for Sligo Rovers, your hometown club.’

“I was [later] given the choice of soccer or GAA. I’m only a light wee fella, so I took the easy way out,” he laughs.

The player-manager of Sligo at the time was Tony Bartley, whose arrival at the club more or less coincided with Fagan’s. As a young amateur, Bartley had been with Everton and Bolton, before going on to represent Bury, Oldham, Chesterfield and his hometown side Stalybridge Celtic.

After making over 200 appearances in the lower leagues in England, Bartley arrived in Ireland amid high expectations. In addition to providing the club with a greater threat out wide, the Mancunian brought an increased level of professionalism to the set-up.

“In them days [before Bartley], you only learned yourself,” Fagan recalls. “There were no coaches or anything like that.

It was an Englishman coming over to Sligo, so that would have created great interest.

“It would give you great incentive to sign for them, because you think he would bring you on better.

“He wasn’t a bad player, he was a left winger, but the facilities we had years ago, they were crap. He was trying to make us do something inside a small room — heading a ball up onto your shoulder and onto your head again.

“We were used to just getting a ball and running, playing six or seven-a-side.

“When he came, he introduced a couple of full-timers to play with the part-timers. You were playing with a full-timer from England — people thought that they were better players than us, it didn’t always work out that way. But when you come in from England, you’re the bees’ knees.”

2. A mixed bag

Yet while Sligo hit great heights during Fagan’s 20-year stay as a player, long-term consistency was never their forte.

Sligo is down away from everyone and it’s very hard to entice players over even from Dublin — they wouldn’t fancy coming down. So what you do, Sligo had a busload of players coming every Sunday. There were only four or five locals that were there and the rest of them were from Dublin years ago, and then there was a gang from the north.

“It was only on a Sunday [for the game] that you would meet players — there was no such thing as training together, they trained wherever they were.

“When Bartley came, he got the basis of the team training in Sligo with five or six full-timers, plus the local lads.

“So he’d only one or two probably coming in from Dublin and that was of greater benefit to the team. It didn’t [always work out] results-wise, but the foundation was there to have the team based in Sligo — half full-time and half part-time.”

He continues: “The rumour was years ago that if you flew over Sligo, you were going to get a game. There was always some fella coming in, playing one or two games, and then going again.

“Once they brought a player from South Africa. The young fella didn’t have a clue about football. Half the town were out there to see what he was like, but he wasn’t that good at all.”

3. Home is where the heart is

Leaving Sligo, Fagan says, was never something he gave serious consideration to at his peak. While some Irish footballers dream of playing in England, to him, lining out in the League of Ireland felt special.

“Shamrock Rovers had about four or five players that played for the international team –Frank O’Neill, Johnny Fullam, Pat Dunne, Ronnie Nolan and all these fellas. That was your aim, to play against them.

“I was lucky enough that when they signed me, my first game was against Shamrock Rovers. It was a Shield match, we were winning 2-0, I scored myself and another local lad, Dessie Gallagher, the two of us were from the same area of Sligo and we were winning 2-0. Then all of a sudden, Shams came back and it was 2-2. It was like nowadays, non-league clubs playing Liverpool and drawing with them, or something like that.

We were as proud as punch, two local lads scoring against Shamrock Rovers, the most famous team in Ireland at the time.”

Fagan combined soccer with a job in Hanson factory, where he worked for 36 years and which produced bathroom scales, before closing in 2001.

After marrying at the age of 20 in 1970, he moved to his current house.

“People say: ‘Did you ever fancy going away?’ I say: ‘No, I was married before I was 21, I live 100 yards from the Showgrounds, 100 yards from the church and 100 yards from my local. What more does a fella want?’

You’d hear rumours that there was someone looking at you. It was never my aim once I got into the team, and it wasn’t that I stayed with them because they were winning. I stayed when we were down and out, and we struggled year after year.”

4. Ending 40 years of hurt

Despite often struggling to compete with the top teams in Ireland, Fagan and co did enjoy some remarkable highs.

In 1977, Sligo Rovers won the league title for the first time in 40 years and the second occasion in their history, finishing a point ahead of Bohemians. It was a tense climax, as they needed to beat Shamrock Rovers in their final game of the campaign at the Showgrounds.

“Gary Hulmes got the first goal. The place was jammed.

“So we were winning 1-0, it was Jimmy Magee’s son, Paul, he equalised and you could hear a pin drop in the Showgrounds. Chris Rutherford and Paul McGee then got a goal each and we won 3-1.

“It was massive and as a local, it was better again to be on the [Sligo] team to win it for the first time after 40 years.”

Fagan says their manager at the time, Billy Sinclair — a Scottish coach who he had previously played for Chelsea and Glentoran — had a big role in the success.

“We were playing a game, we went up to the Showgrounds, Billy was sitting around and he says: ‘Where’s the rest of the team?’ The trainer at the time said: ‘They’re probably down in the Imperial Hotel.’

“Billy went down, he was sitting in the foyer, waiting, and there was no sign. All of a sudden, the lads came in from Derry, I think they were ordering soup and sandwiches. Billy asked: ‘Are ye Sligo Rovers players?’ He then said: ‘You’ve five minutes to get up to the Showgrounds.’

“So that was the attitude. He was coming in and he seen this, so he had to sort that problem out. That season, he sorted it out. The following season, he got full-timers in, all promising young fellas from England. He had contacts, so most of the team were full-timers bar myself. But he had us all training together. He would bring the lads back, we’d be nearly training full-time. The facilities weren’t there years ago. It was always running hard and being sure you were fit enough to do what he was going to ask you.

Our team meetings were before the matches, it was the first time I saw it, we used to have the caps from bottles on a table, where he wanted you to play and the system he wanted. He introduced all that. But the main thing was that we were good individually as well as collectively.

“We had a good run in the league that year, we had exceptional players and a very strong team, but we hadn’t a good panel, so a lot of players had to play with injuries.

“Our trainer would be out with you all week, and then he’d put a big strapping on you and he would say ‘you’ll be sound.’”

In an era in which the League of Ireland was notoriously filled with no-nonsense hardmen and lenient referees, feigning injury or showing what was perceived as weakness by admitting to being hurt was out of the question.

Your leg could be hanging off from a tackle, but you’d be getting up and you wouldn’t give your man the satisfaction of knowing that your leg was hanging off.

“That’s one criticism I have of football nowadays. 99% of fellas that go down, there’s nothing wrong with them, and they want the game stopped, and they want the ball kicked out of play and whatnot.”

5. Cigarettes and alcohol

The drinking culture in the League of Ireland at the time, Fagan says, helped create a bond among players, particularly between the locals and those who arrived in Sligo from elsewhere.

“Most of Billy’s team were young and they liked the pint as well,” he says.

We used to go down and reminisce. Mick Leonard came from Glasgow Celtic. Chris Rutherford and Graham Fox came from Cardiff City. So the four of us used to meet after a bit of training and we used to go down to a wee local.

“We’d have a few pints and I’d tell them what life is like here and they would tell me what life was like at Celtic or Cardiff. Chris and Graham only played with the youth set-up [at Cardiff], but they were away up the valleys against big men, kicking lumps out of them.

“I thought they were all goldfish in a bowl from Britain. But they’re only normal young fellas. The first year when you came over, you’re always trying to do well that you’ll get back the following year [to Britain], but that doesn’t seem to happen. You had to be exceptional.

“Sligo, even at that time, you can imagine, it was small and the lads used to be in digs. The kids were mad about [the foreign imports], they’d be up trying to carry their bags into the Showgrounds.

“They were all young fellas, he got them at the right time, Sinclair, they weren’t fellas that weren’t going to make it. These young fellas had high hopes of doing well. They were coming from a professional outfit over in England. I used to have a fag myself and they couldn’t believe it when you came in at full-time and you’d take out a fag, and you’d be smoking.

That was the culture, it was the way football was years ago. You had a pint after the match and you got talking to the supporters. The team were based in the town, so people could talk to them.

“They weren’t just going in and sticking together, they’d mix in with the people and supporters would get a good feeling for them as well, so it created a positive atmosphere in the town. But it didn’t last long enough. It lasts about two years, then it breaks up and you go back to part-time again, and after another couple of years, someone says: ‘We’ll try the full-time again.’”

Fagan adds: “When Sinclair was there, he made you train as hard as the full-timers, which was very hard, coming back from work and going out training.

“I got sick most nights training because I wanted to play and I wanted to be fit enough to play the game. It stood to me and while I got a lot out of football, I put an awful lot in.”

6. The bad old days

Unfortunately, Sligo never came close to winning the league again during Fagan’s time at the club. In fact, looking at the stats, that ’77 triumph is a remarkable anomaly for a club that generally struggled. In some ways, it was comparable to Leicester City’s 2016 Premier League triumph. Two years before the Bit O’ Red won the title, they finished bottom of the table, in an era before relegation had been introduced to the league. Consider their finishes during Fagan’s time with the club leading up to that incredible 1977 season: 11th, 8th, 8th, 11th, 14th, 10th, 13th, 14th and 10th.

After ’77, it did not get much better for them. Up to the point when Fagan left in 1987, they had the following finishes: 6th, 10th, 8th, 11th, 5th, 12th, 14th, 13th (relegated to the newly created First Division), 2nd (promoted), 9th.

Fagan says a lack of stability and inability to hold onto key players were to blame for the team’s struggles in the league before and after ’77.

The thing about Sligo is that it’s very hard to keep it going, because a lot of players want to go back to England, as Sligo’s so small. It’s very hard to commit for a couple of years to stay here.

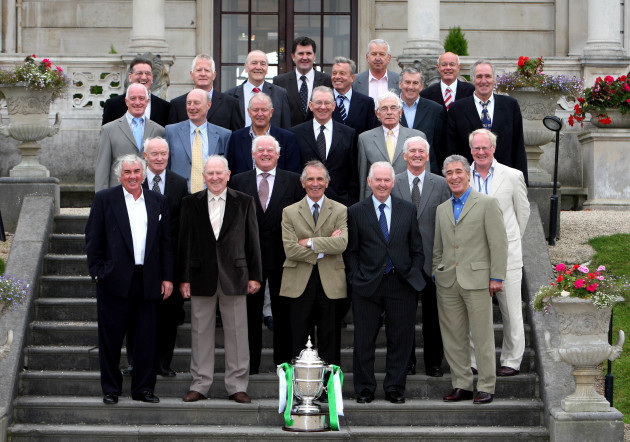

“Even though some of the lads settled down, got married and they’re living here. From the team that won it, Tony Stenson is still in Sligo, Chris Rutherford is in Sligo, Graham Fox, the captain, is in Ballymena. Paul Fielding is in Ballina. So there’s at least half a team that stayed [in Ireland] from ’77.”

Yet for all their disappointments in the league, Sligo had notable successes in the FAI Cup. They reached the final on four occasions during Fagan’s time there — losing out in ’70, ’78 and ’81, before finally lifting the trophy in ’83.

They played Bohs three times in 1970, drawing the first two matches before losing the second replay 2-1, with all the matches in question played at Dalymount Park, “their pitch,” as Fagan points out.

In the ’78 final, Sligo faced a Shamrock Rovers side with grand ambitions. Leeds and Ireland legend John Giles had taken over as manager at the start of the season. He brought players from England such as Irish internationals Ray Treacy and Eamon Dunphy to the league, and believed the club had the potential to compete not just domestically but in Europe within five years.

The Hoops claimed their only major trophy under Giles at the expense of Sligo, amid a fortuitous 1-0 win, with the decisive goal stemming from a contentious penalty decision.

Of that famous Rovers team, Fagan adds: “Treacy and Giles were the main men. You could see Treacy holding up a ball well and Giles would be the artist in the middle of the pitch. Dunphy, something like myself, would just wander about and pick up balls here and there.

It was good football-wise for them to be coming over to the League of Ireland. It gave the place a lift as well, because with Shamrock Rovers coming to the likes of Sligo, you’d get a far bigger crowd if Johnny Giles was coming with them. It lifted the league, but it didn’t lift them as a team, they didn’t win much at all.

“But you have to start off from somewhere, they tried it, and as far as I’m concerned, they’re still trying to do it.”

7. One night in Belgrade

Another memorable occasion occurred earlier that season. After winning the league, Sligo gained entry into the European Cup. It was a period before seeding was introduced, meaning the top clubs and the smaller sides were not always kept apart. Consequently, the Bit O’ Red came up against one of the best teams in Europe at the time, Red Star Belgrade, who would go on to reach the final of the Uefa Cup the following campaign.

The Irish outfit played the first leg away against their illustrious opponents, keeping the score 0-0 at half-time, before superior fitness and ability eventually told, with the hosts running out 3-0 winners, while achieving the same result in the second game at the Showgrounds.

“Most of them fellas played for the Yugoslav international team,” Fagan recalls. “That was an experience going out there — it was the first trip for all us fellas in Sligo.

“[Red Star] were all about six foot and lean. Like ourselves, they used to be smoking away.

“We were training on this beautiful pitch, with the groundsman coming out and asking: ‘Is it okay for you?’ It was like Wembley, and they hosed it down.

The laugh was Sinclair said ‘we’ll go out here and there’ll probably be a few reporters looking at us to see what we’re like’. He said ‘keep everything in order, run in twos and make it look as if you’re a good set-up’. That was grand, everything was going okay. Then we started shooting, everything was on target. Then a few of the lads hit belters, they had a big net behind the goals to stop the ball going far and the lads even put it over the net. So Sinclair says ‘come on, it’s time to go, they’ve seen enough of us’.

“The match was a good experience. Sinclair was good with tactics. He maintained if you put 22 fellas in one half of the pitch, he said ‘no matter how bad you are, it’s very hard for a team to get through you’.

“There was a fella called Dragan Džajić. He got the ball and was a couple of yards away from me and I said ‘I’ll get this fella now’. I slid in for the tackle and I was sliding still and he was about 20 yards down the pitch with the ball.”

8. History makers

Notwithstanding the two memorable European nights, it was probably Sligo’s unprecedented FAI Cup triumph in 1983 against Bohs — a team that had finished eight places above them in the league — which will be remembered as Fagan’s finest hour, with the long-serving midfielder captaining the side to glory.

“We weren’t doing well at all, Paul Fielding was player-manager, he brought Graham Fox back. We didn’t have a strong team, but what brought us together was we were all based in Sligo.

“What galvanised us was playing Cobh in the semi-finals. We played them four times [the first three matches ended up as draws]. There were thousands at the match, even down in Cobh in Flower Lodge. One of the matches we had to get out of the bus, because we couldn’t drive down the road with the crowds.

“We were 2-0 down to Cobh in the Showgrounds. We came back and won 3-2 — that kind of gelled us together.

Then we were going into the final again, playing Bohs on their home ground. [Before the game] they asked the other managers in the league who would win the cup, 11 of them went for Bohs. Patsy McGowan, the Finn Harps manager, said ‘my head says Bohs, but my heart would love to see Sligo winning it’.

“They took the lead and it was a terrible day for a match, the pitch up there was atrocious. But that’s what you had to play on years ago, there was no problem with that.

“Eventually, Tony Stenson got the equaliser and we seemed to be playing better in the second half. All of a sudden, you could feel yourself getting a lift that the [Bohs] players weren’t as good or they were in the wrong frame of mind.

“All of a sudden, Harry McLoughlin received a pass. For a lot of his goals, he could look up and see things. Dermot O’Neill, who played in goals with Bohs, he just caught him off his line and Harry chipped him.”

9. Hometown hero

That improbable triumph consolidated Fagan’s legacy as a Sligo great and to this day, the former midfielder is fondly remembered for all he achieved.

“I’m not into Facebook,” he says. “The mobile phone is an issue for me. The only reason I have one is if I get lost, they’ll find me. I was bringing my grandson out to a crèche about two years ago. He must have told the woman that it was my birthday or something like that, so she said ‘I must do something for Tony for bringing the kids out the whole time.’ So she went on Facebook and couldn’t believe all the headlines. I am an ordinary 5’8 fella. I said ‘this is what people write about you and I can’t do anything about that’.

I had a good relationship with a lot of fellas. It was probably the service I gave to the club and the way I played football [as to why I'm remembered fondly], if you were going into battle, you’d have me on your team.

“I enjoyed a lot of them headlines. It’s nice to get a bit of praise and I think I was doing something right through the years.

“Even all the years after I finished, once they hear my name, people would know who I am.

“I was just coming down for a match last year, I think it was Bohs, I was coming in my gate on the road and I heard two fellas saying ‘that’s him’. I turned around and they asked: ‘Is that you?’ I said: ‘That’s me.’

“I knew what they were saying, I’m greyer now and whatnot. But it’s nice, as people don’t remember bad players.

“I mentioned the fellas in the league side, they were great forwards, but they only stayed a year or two. To me, [a lengthy] service is a whole lot to a club and you’re not kissing badges or anything. I never kissed a badge, because I wanted to play for the club. You see these fellas kissing the badges now and next season, they’re gone to somebody else.”

10. End of the road

For all he achieved, Fagan admits to being saddened and taken aback by the abrupt manner of his Sligo exit. He was 37 at the time, but was captain and had been an ever-present in the side during the 1986-87 campaign, with the club seemingly on the up amid a ninth-place finish, having been promoted from the First Division the previous season.

After 590 games, his time at Sligo came to an end with a meeting that lasted less than five minutes.

“That year, we were doing okay,” he recalls. “We got to the semi-final of the cup in ’87. We played three times [against Shamrock Rovers], including the last game at Milltown. They had a top team at that time, Shams, and they beat us [in the second replay] 1-0 in the 92nd minute at the Showgrounds.

“I know I deserved to be signed for the following year. The management thought I was finished, but how can you be finished when you played all the games?

Sligo Rovers got the best 20 years out of my football life — from 17 to 37. I had to leave then at the end of it, but you have to live with that.”

The decision came about after Fagan had requested a pay rise.

“It was never asked ‘did I want a fiver or £100,’” he explains. “I just said I’m looking for a rise, because I hadn’t got a rise in years. And they just said ‘no’.

“I said ‘well that’s it’. They said ‘that’s it’. So I said ‘I’m gone’. They said: ‘Yeah.’ I walked down the road. It was the loneliest walk. I said ‘there’s 20 years of my life’. They never asked me what I was looking for, and that was the hardest part.”

It was perhaps no surprise that without Fagan, a player who in many ways represented the heart and soul of the club, Sligo were relegated the following season, finishing bottom of the Premier Division table, and not returning to the top flight for another two campaigns.

And while he would never represent the Bit O’ Red in the League of Ireland again, it was not the end of Fagan’s playing career. He subsequently joined Finn Harps, with the team finishing third and narrowly missing out on promotion from the First Division in the 1987-88 campaign. The following season was Fagan’s last, as a broken ankle prompted him to call it a day at the age of 39.

“I went to Finn Harps and I played nearly a year and a half, every game, with broken toes and everything. I was that type of player. It wasn’t ‘oh, I’ve a broken toe, I won’t see you for a month’. They gave me injections before a match to kill it and strapped the two toes together. Then, all of a sudden, one of your own players gives you a ball short, an opponent comes in and nearly kills you. I said: ‘That was okay when I was 18, but I’m getting old now.’”

11. The return

Despite the disappointing conclusion to his time at Sligo as a player, Fagan held no lasting grudges, and agreed to return to the club as coach of the reserves, after former Celtic star Willie McStay was appointed player-manager in 1992.

“I was out of football. I said: ‘I gave enough to football.’ [Willie] came to the house with Chris Rutherford and said to me: ‘Would you be interested in running the reserves for me?’

“So I went back there for three or four years, but after that, Willie went back [to coach Celtic's youth team]. Lawrie Sanchez [in 1994] and Steve Cotterill [in 1995] came, they done very well here and got great jobs out of it. Cotterill has got eight great jobs since he went back to England — he was managing Birmingham City [until recently]. Lawrie Sanchez was manager of Northern Ireland and got another couple of good jobs as well.”

However, as much as he enjoyed being back at the club, various managers’ reluctance to give the players he was coaching a chance in the first team was a source of regular frustration.

When I was running the reserves, there’d be local lads playing, and I’d say if there’s a young fella playing [in the first team], there are 10 other fellas there, surely they’ll be able to look after him and give him the right ball, talk him through the game, help him along, but these fellas weren’t good enough to do that. They were just minding themselves.

“Cotterill and Lawrie would say ‘we’re only here for a short time,’ and it was results they wanted. I was saying: ‘What’s the sense in having a reserve team if they’re not going to give them a chance?’ Even nowadays, with the team, they’re bringing fellas in from England, but Sligo are running U15s, 17s and 19s. If they don’t start progressing the young fellas into the first team, what’s going to happen if the bubble bursts?”

12. Life after football

After the ankle break suffered in the 1988-89 campaign ended his League of Ireland career, it was only in February last year that Fagan finally went ahead with an operation on it.

“I was taking painkillers for years and years afterwards. It didn’t heal up that well. I was suffering the whole time.

I couldn’t go on with it, so [I visited] the doctor up in the sports clinic, it was about €200 to see him, I said to him: ‘How much will this operation cost?’ He said: ‘€5-6,000.’ I said to him: ‘I’m an ordinary labouring guy, I worked in a factory all my life, I wouldn’t have money like that.’ He just looked at me and said: ‘I do a public clinic in St. James’s Hospital and I’ll put you on the list.’

“And for three years, I refused the operation, because I had a son-in-law, who was dying of cancer. I was bringing four kids to school. 19 February, two years ago, he died and left two kids. The daughter is a teacher and she said: ‘I’ll be taking a year off, if you want to get your ankle done, get it done now after three years of postponing it.’ [The doctor] said to me if I postpone it anymore, I’d have to go to the end of the queue, so I got it done, and I haven’t taken a painkiller in a year.

“That’s life and it’s not all rosy. We’ve two grandchildren, eight and five, they lost their dad at 37, it’s not easy and it affects the whole family when that happens. You’re looking at your daughter, she’s only young and she’s two kids and it’s a lonely life. You have to step in and help them as much as you can and there are another two boys, seven and nine — I had two girls and [my daughters] had two boys each.”

13. Mr Sligo Rovers

Nowadays, Fagan remains an avid Sligo Rovers follower, while also acting as a sort of unofficial ambassador for the club. He has been less than impressed with the team of late, as they have hovered perilously close to relegation from the Premier Division, only staying up on the final day last year. This season could be similarly problematic, with Gerard Lyttle’s men currently ninth out of 10 teams.

“We’ve a small community down here and it’s very hard to get a main sponsor that would pay the type of money [needed], so we’re depending on the people of Sligo and the same person the whole time for funds. They’re an amazing club to do it, but they have to get back to winning ways, so hopefully things turn around.”

He continues: “I’m there with my grandson and son-in-law every home match. I would have fellas tipping me on the shoulder. They would say: ‘How’s it going Fago?’ I would say: ‘How’s things?’ They look at me and know I can’t [figure out] who they are. They say: ‘I played with you for two seasons.’

“I played with hundreds of players throughout my career. They would know me, but it’s very hard to think of all the players that I played with and to know them after all these years.

“But it’s good that I’m still around. [Former players] Johnny Brooks and Kevin Fallon, he was manager of the New Zealand team, when they come back, one of the old committee men will ring me and say: ‘Kevin Fallon or Johnny Brooks is in town, would you go and meet them?’

Johnny Cooke came over from Manchester United in 1970, but you could see he was lost, he was probably looking around and saying: ‘Last week I was with Manchester United, this week I’m with Sligo Rovers.’ It was probably an awful let-down for him and he was a very quiet young fella.

“But he was a good footballer and it happened that Sligo Rovers were running a Youth Cup last year and they had teams from England over. And Johnny is a scout for Manchester United and he said that he was at a meeting, someone said that there was a tournament over in Sligo and [asked] who’d like to go.

“After nearly 48 years, he put up his hand and said: ‘I’d like to go.’ It was his first time back. Someone got word to me that he was coming. He phoned me and said: ‘I’ll be up at the match tonight.’ It was over a weekend and he said: ‘How will I know you?’ I said: ‘I’ll be the man with the grey hair and I’ll be on crutches, because I got a job done on my ankle.’

“So it was great meeting up with him and he hasn’t changed a bit. We reminisced, and David Pugh and Tony Stenson came up to meet him. We went down to a local hotel, had a drink and after 48 years, it’s nice that he came back and met us.

“We talked about how we got on in life, you know?

Johnny was a lovely dainty footballer, he’d be like Georgie Best with the long hair. He said: ‘Fago, what happened you?’ I said ‘the ankle [broke], got it in football’. He said: ‘I got the same injury as you.’ I laughed and said: ‘What did you get it from?’ He just thought: ‘What is he after saying, I never tackled or anything like that?’

“But it was nice to meet him again. I’m lucky that I’m around the place. I showed him a couple of the old places around Sligo that I used to go nearly 50 years ago. People say I’m the only fella that was around from that time that’s still around.”

And finally, as the interview is drawing to a close, having been kind enough to chat for more than an hour and a half, Fagan pauses, for once momentarily lost for words, before reflecting on our conversation.

“This is the real Tony Fagan,” he says. “There’s two sides [to a story], but this is a genuine fella. It wasn’t all rosy, people hurt me as well, though you just kind of get on with it nowadays.

“I’m able to get up in the mornings. People are looking for everything in life, but just be happy with what you have, and if it gets you by, that’s the main thing.”

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!