YOU CAN FIND a Tony Sheridan Premier League trading card on eBay. Here’s the description:

“One original card from the set ‘PREMIER LEAGUE 93/94′. This is a rare card with a limited edition – issued by MERLIN. CONDITION – HIGH QUALITY.”

Rare? Limited edition? High quality? Sounds like Sheridan, alright. The card will set you back £1.50. About €1.77. And that certainly sounds like Sheridan too. Undervalued. Under-appreciated. But a real find. A diamond in the rough.

The card is from the 1993/94 season, when Sheridan’s career at Coventry City was taking off .

It had been an exciting twelve months.

In October 1992, there was a Premier League debut in front of 30,000 at Elland Road just days after turning 18. He had to wait a while for another opportunity but manager Bobby Gould had faith. There were a string of subsequent first-team appearances in the early part of the following campaign. He was an underage Irish international. After a baptism of fire, he had turned a corner.

A product of Crumlin’s famous football nursery Lourdes Celtic, Sheridan had trialled with a handful of English clubs as a teenager – Leeds, Brighton and Gillingham under Damien Richardson. He finally settled on Coventry where Terry Butcher was player-manager. But, at 16, he found it tough. The routine was strange. Famously, Sheridan would try and sleep to pass the time. Within a few months, he’d had enough.

“At the start it was hard”, he says.

I came home for Christmas one year and I made my mind up before I left that I wasn’t going back. I was back in Dublin for about seven months. And then I got a phone-call. It was Bobby Gould. He said, ‘If you don’t come over, I’ll go to Dublin myself and drag you back’.

I went back over and we had a good chat. I asked for a bit of freedom on the nights that we were free. I asked for Wednesday at 10pm to be pushed back to 10.30pm because we’d go swimming or go to the cinema. And on a Saturday, I asked for 11pm. And I was given all of that. It was boredom that basically made me go home in the first place so he was good to me and then gave me my debut. I think he had a soft spot for me. He was a great manager. He didn’t mess around. If he wanted you in the team, he put you in the team”.

It was a solid if unspectacular group. In 1992, Gould was in his first season as manager and the freshness seemed to have an impact. They won six of their first eight games and were second in the table before they jack-knifed. They were rescued by Micky Quinn who scored 17 times in the league despite only arriving in November. He developed a neat understanding with Zimbabwe international Peter Ndlovu but the side’s inconsistency was an issue.

In the middle of an eight-game winless streak, Sheridan was given his moment and started against Leeds. He remembers snippets of the game but not much. On the hour-mark, Eric Cantona was introduced for the home side. For ten minutes – until he was replaced by Phil Babb – Sheridan graced the same pitch as the mercurial Frenchman. Not that the lifelong Manchester United fan knew it at the time.

I’d be down The Stoneboat – that’s me local where I’d go for a pint – and lads would come and say it to me, ‘Do you know Eric Cantona played in that?’ That’s how much of a blur it was for me at the time. I only found out that Cantona played in that fixture about four months ago.

The way I looked at it was that when the game was over, I was on me weekend back home. I made me debut and that was it. That was the easiest part – getting into the first-team. The hardest part was staying there. Debut? I just went out and played football. It was just another game”.

An injury ensured Sheridan’s foray into Premier League football was put on hold temporarily. But when the 1993/94 season rolled around, he was starting in midfield at Highbury as Quinn scored a hat-trick in a memorable 3-0 opening-day victory over Arsenal. Four days later, he started again in a win over Newcastle. And there was another start in the draw with West Ham. After a few appearances from the bench, including at Anfield in a 1-0 win over Liverpool, Sheridan returned to the starting lineup for a game against Norwich at Carrow Road.

And then, just like that, his mentor Gould resigned.

“He told me he was resting me for a league game against QPR and then, all I remember is hearing that he’d resigned”, says Sheridan.

QPR thumped five past Coventry that day. Afterwards, Gould memorably sat in front of the press and said:

Gentlemen, this will be short and sweet. I have just informed the players and the chairman that I have resigned. A statement will be made on Monday and that is all I am going to say”

If you can pinpoint a moment when Sheridan’s career trajectory began to dip, this would be one.

Gould’s assistant, Phil Neal, took over as manager. And Sheridan quickly became a forgotten man, despite his litany of starts earlier in the campaign.

“I didn’t really see eye-to-eye with him”, he said.

“He was a completely different person. Bobby Gould trusted us. Phil Neal was the opposite. I didn’t think he was any good as a manager. As a coach he was okay but as a manager he was fairly two-faced. He never told me the truth. I worked my way back in, played in the reserves and done well. But it was a downward spiral. Neal played the same team week-in, week-out. And you were resigned to saying ‘Nothing’s going to happen here’. In hindsight, I would’ve gone, ‘Fuck it. I’m going to work me socks off and maybe a reserve team I play against will see something in me’. But I was young. I was 19 or 20 and it didn’t work out”.

Neal’s reputation had taken a battering owing to his role as an assistant to Graham Taylor during England’s infamous World Cup 1994 qualification campaign. The fact that Neal was part of the managerial team that failed to get England to America was not lost on Sheridan, who gleefully turned the screw on occasion – something he feels, with the benefit of hindsight, was just another reason for Neal to shun him.

“He would always go with experienced players”, Sheridan says.

“Looking back, I think he felt his job was under threat. But I didn’t like him. We had a fall-out. He used be a bit arrogant towards the Irish lads. We (the Republic of Ireland) had qualified for the World Cup and they hadn’t. And I kept on singing to him, ‘When you go, will you send back a letter from America’? And then I’d keep at him, ‘Phil, are you going to America? No? Ah, Phil Babb is going. He’ll send you back a letter from America’. And then I’d burst into the song”.

Maybe that had something to do with me not getting my game! But that’s what football was like back then. It was banter. You had a bit of craic. And some people took it personally. And he took it a little bit more personally than others”.

Sheridan didn’t play a single minute under Neal’s management and grew increasingly disillusioned. Time became his biggest enemy. And he had lots of it.

“You have so much time on your hands – that’s the problem”, he says.

“Some of the lads weren’t getting in the team so we’d go to the bookies and for a couple of pints. You got into a rut and got into little habits. There were a lot of Irish in Coventry – not just footballers. It’s just full of Irish people. And it was like being back at home with your mates. You’d turn around and it’d be, ‘Go for a pint?’ Now, we wouldn’t be going on five-day benders. But I was a bit down in the dumps and it kept you a bit sane. Just to get away from the hardship of it.

“There’s not much loyalty in football. People saw what me and the other guys were doing – and we weren’t misbehaving or anything, just having a couple of pints – and that was it. We went our separate ways. It was hard because, even though I’d made it to the first-team, nothing else came out of it. If I knew then what I know now, I would’ve done something different”.

Just a few years later, Sheridan was lamenting the way his time at Coventry evaporated and the role he played in it.

Part of it was just being a young fella away from home. Plus sometimes you got so bored you thought that drinking and having late nights was the way out. You’d go home to bed, you’d have a few drinks on you and you wouldn’t remember anything, you just wanted to forget about home and all that. Part of it was frustration and – excuse the language – part of it was `fuck him, fuck him, what does he know’. At the time I thought I knew better but I know now I shouldn’t have done that stuff. I should have just got on with it. I did try my hardest for seven or eight months but after that I just didn’t care, I just didn’t care.”

It didn’t help that Sheridan always found himself caught in the middle of a myth.

There’s a scene in Michael Winterbottom’s 24 Hour Party People about the rise and fall of Factory Records where Tony Wilson (played by Steve Coogan) quotes John Ford:

“When you have to choose between the truth and the legend, print the legend”. It applies so much to Sheridan’s career.

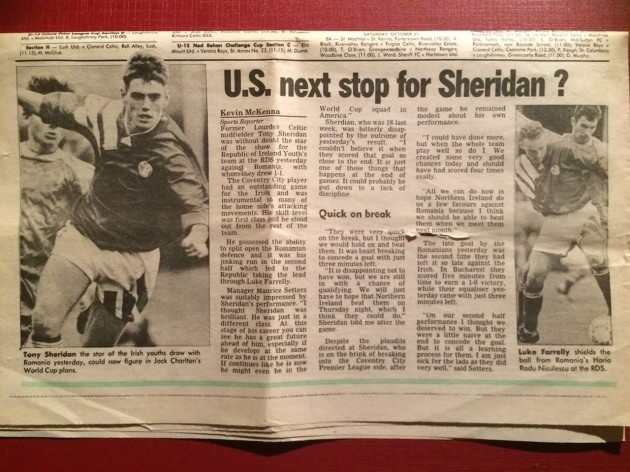

In 1992, assistant manager for the Irish senior side and underage boss Maurice Setters was glowing in his praise after Sheridan’s performance in a U18 qualifier against Romania at the RDS.

“I just thought Sheridan was brilliant”, he said.

He was in a different class. At this stage of his career, you can see he has a great future ahead of him, especially if he develops at the same rate as he is at the moment. If he continues like he is now, he might even be in the World Cup squad in America”.

At the time, Sheridan was still to make a first-team debut for Coventry. Yet, unfairly to him, it seemed others couldn’t help but get carried away.

In early 1994, when Sheridan was being frozen out at Coventry and without a game in months, Graeme Souness supposedly wanted to sign the then-19-year-old and bring him to Liverpool in a £1 million deal. But it never happened because Souness was sacked. Sheridan was told the story years later when trialling at Southampton, where Souness was then in charge.

“There was a guy at Southampton who was a scout for Souness and who had lived in Leamington Spa which is half an hour from Coventry”, Sheridan remembers.

“He came to have a look when I was there. I was 18/19 and he probably said to Souness that I had potential to go all the way. And he said Liverpool were putting in a bid for me for £1 million when Souness was in charge. But the deal fell through because Souness got sacked. That’s how well I was doing. Now, that’s speculation. I’m not sure why the guy would say it if it’s not true and, years later, Souness had me over at Southampton on trial so he obviously liked me”.

It says a lot that Sheridan still doesn’t know if the story is true or not.

Vulnerable, he badly needed advice when struggling at Coventry but he was isolated and still a very young man. There were impulses and excesses and it didn’t help that Neal was sacked in early 1995. Another transition. Another new man. Maybe another chance to impress? Maybe not.

“Ron Atkinson took over but never gave me an opportunity”, Sheridan says.

“I went to his office and asked why he wasn’t playing me. So he told me I could play in the midweek reserve game against Nottingham Forest. And he took me off after 15 minutes. So that was really it”.

In the summer of 1995, Sheridan was released. It had been 20 months since he last played a competitive game in England. There was a trial with Bolton and Liam Brady wanted to take him on loan to Brighton. But Sheridan wanted to get his head straight and returned to Dublin for a few weeks. Shelbourne’s Ollie Byrne reached him at home, sold him the club and the rest is history.

If you can pinpoint a moment when Sheridan’s career trajectory began to soar, this would be one.

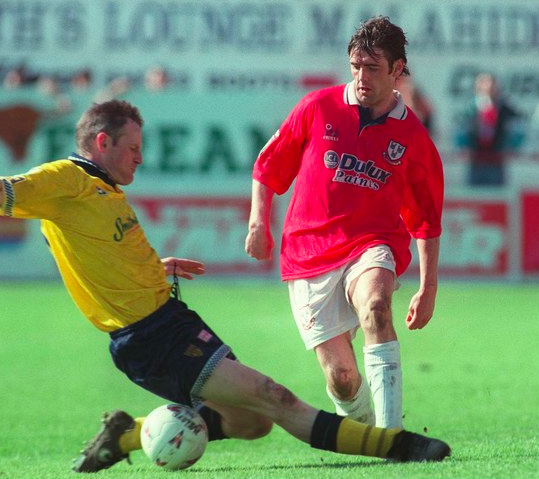

An old friend was in charge of Shels at the time – Damien Richardson – and Sheridan exploded onto the domestic stage upon signing, dovetailing superbly with the magnificent Stephen Geoghegan and conjuring some moments of incredible skill.

With his jersey hanging outside his shorts and the Oasis haircut, Sheridan proceeded to light up the mid-90s with his mercurial left-foot. Without one for so long, he was the league’s rock and roll footballer. He finished his debut campaign by delivering two outrageous FAI Cup moments.

In the semi-final win over Sligo Rovers, Sheridan took off on an 80-yard run before delicately lobbing the goalkeeper from the edge of the box with the outside of his boot.

And at Lansdowne Road a few weeks later, there was the definitive Sheridan goal. With 10-man Shelbourne trailing to St. Patrick’s Athletic and the game ebbing towards injury-time, Sheridan tried to make something happen on the edge of the area.

Attempting to ghost past one challenge, the ball bounced off a Pat’s defender and hung, momentarily, in the air. Sheridan caressed it with the outside of that left-boot and conjured an inch-perfect volley that dropped into the top corner.

In the replay, Sheridan scored again as Shels came from a goal down to win it. His first season back home and already he was a winner. More than that, he had crafted a persona. He was flamboyant and brilliant and effortless. Shels’ fans adored him but, so too, did plenty of supporters from other teams. He was just that kind of player. But Sheridan is quick to acknowledge the overall strength of the Shelbourne squad at the time.

“The players around me allowed me to express myself. I got the adulation but it was mainly about them”, he says.

There were times when I’d win ‘Man of the Match’ and I’d come off the pitch and think, ‘How the fuck did I win that? I was fucking brutal’. And even the lads would give me stick because I’d be Man of the Match in nearly every bleedin’ game I played. The likes of Brian Flood, Mick Neville, Greg Costello, Ray Duffy, Stephen Geoghegan. The camaraderie was terrific, the harmony was frightening. Myself and Stephen…straight away, as soon as I came to Shelbourne, it was telepathic between the two of us. I’d get the ball, put it in a spot and there was Geogho to put it away. It was a pleasure to play with those lads.

Everyone that played for Shelbourne were all quality players. But I look at the league now…When I played, you’d go to Pat’s and you’re playing against Eddie Gormley. You’d go to Derry and Liam Coyle. You’d go to Cork and Patsy Freyne. Galway had Jimbo Brennan. Dundalk and Brian Byrne. You had good players everywhere. Now? The players are being asked to play a certain way. You don’t go and express yourself”.

In 1996, Sheridan was crowned the League’s best player. There was talk of how he was too good to be in the League of Ireland, that he was wasted there. Good enough to play in England. More talk. And, just a few months after the Cup success, he got the call from Southampton to return to the UK and spent two weeks on trial with them. He stayed with Souness in his mansion, was wined and dined and sent back on a first-class flight from Heathrow.

“I had to sit in beside two businessmen in suits and I was there in my tracksuit – they must have thought I was a drug dealer”, he told Mary Hannigan a few months later.

But, rather inevitably, nothing came of the Southampton link. He returned to Shels and won another FAI Cup in 1997 against Derry City. The following year, the dream of a three-in-a-row was destroyed by Cork City, who pipped them in a replay. And then Richardson left – arguably the finest League of Ireland team to never taste league success. In 1998, it looked like it was going to happen only for St. Pat’s to win it on the last day of the season.

When Dermot Keely arrived as boss, subsequent contract talks became fraught. Sheridan wanted more money, Shelbourne held their ground. Then there was a call from Ronnie McFall at Portadown. The deal was a good one. And Sheridan went.

“Probably the biggest mistake I ever made in football”, he says.

“It was an absolutely diabolical standard of football. It was farcical. I didn’t enjoy it – not because of the people or anything like that – there was just no football. It wasn’t like I was playing with the lads at Shelbourne. It was nothing like that”.

He only stayed for one season but still managed to conjure one of the greatest goals you’ve never seen.

“People ask me about the Cup final goal but for me, this was the best goal I ever scored in my life”, he says.

It was against Newry – Johnny McDonnell was playing. They had a corner and our goalkeeper caught it. He knocked it on and I was on the halfway line – just inside the circle. The ball came over my shoulder and I controlled it with my right foot. And before it touched the ground, I smacked it with my left. And it just flew into the corner. More of a half-volley. I rang home and asked them to record it for me so I could see it. I heard that Jackie Fullerton, the BBC reporter in Northern Ireland, turned around and said it was the best goal he had seen. And that’s a real honour. It’s just instinct. No-one knows how you do it. It just comes to you”.

From there, things got silly. In August 2000, Bobby Gould was named as manager of Cardiff City. Sheridan picked up the phone, called the man responsible for handing him his debut in English football and engineered a one-year deal for himself. But he’d never play a competitive game for the Division Three side.

“I chanced my arm with Cardiff”, he says.

“At the time of signing, I was working in James’ Hospital. And after five or six months and figuring it all out in Cardiff, I went to Bobby and said there was no point in being there because I was earning more back in Dublin. I asked if he could do anything to get me better terms but he said he couldn’t. I was busting a gut in training, training on my own because there was no reserve team. I was going to be included in the first-team at one stage. I’d just been back home and Alan Cork was in charge then. He said, ‘You were going to be in the squad for this week but you’re half a pound overweight’ and I went, ‘Ah, here. This is not for me’. I upped sticks and came back home”.

Sheridan was 26 when he returned. He wasn’t even at his peak yet. But over the years that followed, he could never find a consistent home. He had two further stints at Shels but seemed to yearn for the team he had been a part of before. It just wasn’t the same anymore.

After Portadown, the worst thing I did was not sign a contract with Shelbourne. I signed back with them three times in my career. That’s the club that belongs to me. It’s deep inside my heart. There’s no other team for me”.

Along the way, there was a decent season with Dublin City, forgettable stops in Glenavon and Waterford before a brief renaissance with Shamrock Rovers. And then that was it.

At 31, it was all over.

Ever since, it’s been about trying to get back. There was talk of a coaching role alongside Pat Fenlon at Rovers but he didn’t have the necessary qualifications so he went and studied for his Uefa ‘B’ Licence and it came through last May. At the same time, there was some supposed involvement with a team in the Isle of Man – Elann Vannin FC. But that’s off the table now, described by Sheridan as ‘a bit of a bleedin’ shambles’.

In many ways, the ‘Tony Sheridan’ persona has counted against him since finishing playing. Still involved with the youngsters at Terenure, he desperately wants to coach within the League of Ireland but he doesn’t fit neatly into a category. He’s not the studious, serious type. He’s not the tough, uncompromising, larger-than-life guy. He’s not the new kid on the block. He loves the game to be played like he played it. And maybe that’s the biggest problem.

“You look at the League of Ireland now and there are only a handful of new managers brought in”, he says.

“You have the likes of myself and Stephen Geoghegan and other players too…you’re trying to get the opportunity to work with a team in the League of Ireland. I feel I have a lot to offer. I see the game completely differently from other people. I see things a lot quicker.

From the time I could kick a ball, it was the way I played football. You look at Messi – it doesn’t matter if he’s in the Nou Camp in front of 90,000 or in Sundrive Park or Bushy Park playing in front of 10 or 12 people. That’s the way I was. I just wanted to play football”.

I’d like to be remembered as a player people loved to go and watch. Hopefully I did give them something they enjoyed”.