THE MURMURS ECHOED around that old Victorian cottage. Even by 2001 standards, it seemed so quaint, this tiny little building, transported from a Thomas Hardy novel to the corner of Lansdowne Road.

Fifteen seconds before he entered the room, an overexcited cameraman rushed through the door, face red, eyes wide. “He’s coming, he’s coming,” he shouted.

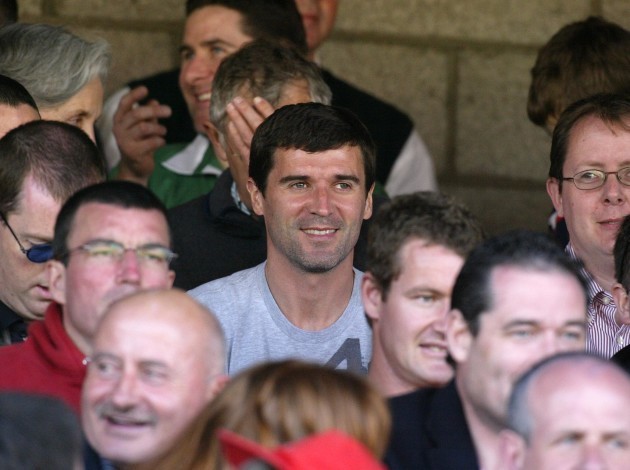

That was the effect Roy Keane had, turning middle-aged men into childish schoolboys, ahead of what should have been a routine press-conference.

It was the day before Ireland’s 1-0 victory over Holland in a World Cup qualifier, a game most people remember for two things, either Jason McAteer’s goal or Keane’s crunching tackle (blatant foul) on Marc Overmars.

Most but not all. A couple of years after Ireland’s win against the Dutch, Brian O’Driscoll sat down with this reporter for some product launch, and spoke about Ireland’s 1-0 win over the Dutch without once mentioning the game.

“I’m a huge admirer of him,” O’Driscoll said of Keane in 2003. “That never-give-up mentality, there’s something we can all take from that. His pre-match comments really resonated with me. Still do. They struck a chord – made me think, ‘we can do better; we should aim higher’.”

You trace your way through old scrapbooks, finding Keane’s words from that 2001 press conference, quickly noting they weren’t emotive lines stolen from Shakespeare’s finest works. Yet they left their mark. “The days of us being little old Ireland have to go,” Keane said in his pre-game address. “We have to show more ambition.”

You think little more of this for another decade-and-a-half. And then you hear Donncha O’Callaghan mention the same press conference, the same words. More recently in the last 12 months, Alan Quinlan and Jerry Flannery have also spoken of Keane’s influence on Munster’s 2006 and 2008 Heineken Cup winning team and it forces you to double-check things.

Eddie O’Sullivan takes a call. No, Keane was never mentioned in a team-meeting, a half-time talk, or a pre-game tactics board during his reign as Ireland coach. Why should he have been? Keane wasn’t going to play at Twickenham, the Stade de France or wherever Ireland were pitching up. He wasn’t relevant.

Yet he had an effect. Here’s O’Callaghan, writing about Keane in his 2017 column for The Times. “When Keane said what he did before the Holland game, it made me think, “f*** it, he’s right. Why should I just tog out and be a number? Why shouldn’t I want to achieve more?”

Keane made me realise that was nowhere near enough. Long before Conor McGregor said we’re not here to take part but to take over, Keane lived those words. There he was at Nottingham Forest, thundering into Bryan Robson. There he was at Manchester United doing likewise to Zinedine Zidane. With every action the implicit message was, “I’ve done it. Now you do it.”

O’Callaghan would. So, in time, would Munster, Keane speaking to Declan Kidney’s squad the day before they played Sale in a 2005 Heineken Cup match. “He lit a fire under us,” O’Callaghan said. “I’m from Cork, just like him. When he made it at the highest level, it made me think: “well, why the f*** can’t I have a decent career too?”

It’s an exaggeration to say Keane changed Irish rugby. Men like O’Driscoll, Ronan O’Gara, Keith Wood, Warren Gatland, Declan Kidney and O’Sullivan were the ones who did that.

But it’s not too much of a stretch to say Keane altered the way Irish rugby people thought and spoke. Two years after saying Ireland’s intention was to beat Holland and go on and win the 2002 World Cup, Keith Wood pretty much stated the same ambition ahead of the 2003 Rugby World Cup.

“None of us believed we’d win in 1999,” Kieron Dawson, who played in that awful defeat to Argentina in Lens, says now. “But by 2019, I’d say every person in that Irish squad went to Japan thinking they’d do it.”

That’s some psychological turnaround, largely dictated by results. When you examine Ireland’s record in the ‘90s – 11 straight defeats to France; 10 defeats and a draw with the Scots; eight defeats to England, and, predictably, 13 straight defeats from 13 meetings with Australia, New Zealand and South Africa – you can see why they didn’t harbour any thoughts of glory in 1999.

Then when you consider the historic boxes ticked since – a first victory in Paris in 28 years (2000), first win over Australia in 23 years (2002), 2004 victory at Twickenham (first since 1994), 2004 defeat of South Africa (first since 1965), the 2009 grand slam, the victories over the All Blacks – you can understand how expectations changed.

And you keep getting drawn back to those couple of sentences Keane made before the Holland game in 2001. Why would O’Driscoll, O’Callaghan and Quinlan mention them, unprompted in three separate interviews or columns, across a 17-year time-span?

“Among my generation of Irish rugby players,” O’Callaghan wrote, “he was the man many looked to and drew inspiration from. Every trophy won by Irish teams from 2000 to, I’d say, 2012 was backboned by players who would have had him as a role model and de facto sports psychologist.”

Flicking through Ronan O’Gara’s autobiography, further evidence to support O’Callaghan’s assertion is found. “It’s strange to have a hero who is only a few years older than you,” O’Gara wrote, “but hero is the best word to describe my admiration for him. I always loved his drive. His attitude. The way he turned himself into a great player with less talent than other top players.”

O’Gara’s old rival, Johnny Sexton, is another Keane fan, taking his side in the Saipan civil war, inspired by the stand-out performance in the Cork-man’s career, the come-from-behind win against Juventus in the 1999 Champions League semi-final.

But Sexton is 34. The younger generation of Irish rugby player only know of Keane the player through YouTube posts or from the words of older people. But video clips can’t recreate the impact he had on matches. In today’s world, Keane is better known as a cranky, outspoken pundit.

You thought of this again after Twickenham, two weeks ago, when the outcry from a 12-point defeat reminded you of Keane, sitting in the studios at Sky, putting Jamie Carragher or Gary Neville in their place.

All that visible anger on social media made you think perspective is the first casualty of the digital world. So you looked at a few stats. Over the last 20 years, Ireland have achieved 18 top-half finishes in the Six Nations, more than anyone else. The previous 20 years saw them finish with seven wooden spoons.

Yet Keane, the player or the pundit, wouldn’t have cared about anything like that, nor would he have excused such a dismal performance.

And in a nod to his standards, all these little Keaneites – in mainstream and social media – bemoaned the team’s mentality.

That’s the price you pay when you give up the notion of being ‘little old Ireland’.