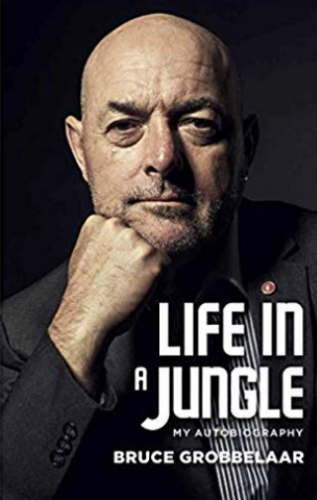

THE FOLLOWING PASSAGE is an extract from ‘Life in a Jungle’ by Bruce Grobbelaar and Ragnhild Lund Ansnes.

I didn’t hear anything from Liverpool, at least not immediately.

The English season might have been over, but the American one was not long under way. Phil Parkes had departed Vancouver for Chicago Sting. I had fully hoped to succeed him as the Whitecaps’ number one, but in my absence Tony Waiters had signed the Scotland international David Harvey. That move was ill-fated and after an indifferent start I replaced him as first-choice goalkeeper for the rest of the 1980 season.

As my reputation grew in the NASL so too did speculation about a return to England. Tony Waiters told reporters: ‘My phone has been red-hot recently with English clubs chasing Grobbelaar and if I were to make him available, a deal would be on immediately.’

Liverpool as it turned out were just one of those clubs. In the midst of this speculation I was told to travel to England to meet Bob Paisley.

I was excited but apprehensive as well because I’d learned quickly how fragile the world of football is. It had seemed that I had a chance of signing for West Bromwich Albion but I didn’t. It had seemed that Bob Paisley was interested in me for Liverpool but then the line went dead for a while. Would it happen again?

I flew direct to London Heathrow and caught the train to Birmingham, as Liverpool were playing Birmingham City that day. I was asked to meet Bob Paisley and Peter Robinson, the club’s secretary, in a quiet room but the meeting would raise more questions than answers.

Paisley eventually shuffled in and mumbled: ‘You’ve played in the UK at Crewe, well, this is not Crewe, this is Liverpool Football Club. This is Peter Robinson who does all the admin. I see that you’ve got an ancestral visa. Good, you’ll hear from us.’

Then he walked out the door. I was confused and looked at Peter Robinson, who just said, ‘Well, you’ve heard the man, you can go back now.’

It didn’t make me any wiser. So I returned to the airport and took the long journey back to Vancouver. I didn’t even get a ticket to see the game.

Months passed and nothing came from Liverpool. The NASL season was coming to an end at Vancouver. After losing 1–0 to San Diego at home, Tony Waiters came to me and said, ‘Listen, two very important people have come to see you. Bob Paisley and Tom Saunders from Liverpool want to ask you a few questions.’

As I walked into the room, Paisley says, ‘Grobble-de-jack, would you like to play for Liverpool?’

‘Yes, Mr Paisley, I’d love to play for Liverpool.’

‘That will do for me.’

And with that they turned round and walked out the door. I didn’t see them again for another six weeks.

What I wasn’t aware of then was that there was a reason for these long silences. A months-long battle between Liverpool and the Home Office had ensued for them to get me a work permit in England. Without one there was no way they could complete a transfer. The conditions then were much more onerous then than they are now: Liverpool had to convince them there was no one in the UK who could do the job I’d be able to do as understudy to Ray Clemence — who was 32 years old at the time.

It was only when working on this book that I was shown the letters of correspondence going back and forth between Liverpool Football Club, the Department of Employment’s Overseas Labour Section, the Football Association and the secretary of the Professional Footballers’ Association. And it was quite moving reading Bob Paisley’s arguments in a letter of 3 December 1980: ‘We wish to make application for a work permit for Bruce Grobbelaar a professional goalkeeper of outstanding potential who at present plays for Vancouver Whitecaps in the North American Soccer League. He is a Zimbabwi [sic] National and also the holder of a South African Passport.

‘You will appreciate that in an effort to maintain our position as one of the most successful clubs in Europe it is necessary to extend our scouting activities far and wide to find an understudy for Ray Clemence, who is now 32 years of age and we are convinced that Bruce Grobbelaar is the player we require. He is a current International player having represented Zimbabwi [sic] since that country became independent.

‘Mr Tony Waiters a former English International Goalkeeper and one time employee of this club, is of the opinion that Bruce Grobbelaar is the best goalkeeping prospect he has ever seen and we are sure that we cannot possibly get a player of equal status in this country.

‘To be able to employ someone from abroad, the club also had to ‘guarantee that no person who is ordinary resident in the United Kingdom will be displaced or excluded in the consequence of the engagement of the overseas worker in question’.

In the application it also said the club had 30 contract players at the time and seven apprentice professional players. It said I would be getting £450 per week plus the same bonuses as the other players. The bonuses were ‘£10,000/20,000 per annum, depending on success’.

It also said that at the end of 1980 the highest rate of pay was £952 per week. I know that Tony Waiters thought highly of me, but it is still touching to find his words about me in an official document all these years later. I feel proud and very honoured to be thought of this way — that Bob Paisley would make the effort to try to convince the authorities that I was the only man for the job as Clemence’s understudy, instead of not having to go through the extra trouble by signing someone from Great Britain.

But the Department of Employment — Overseas Labour Section — was not convinced; I had only played two games for the Rhodesia national team and two for Zimbabwe, so they did not see why I would be this extraordinary international reinforcement that couldn’t be found in the UK. So they asked for advice from the PFA and the FA in a letter of 14 December 1980:

‘On the evidence available we have some doubts as to weather [sic] Mr Grobbelaar can be regarded as satisfying the ‘Internationally established’ rule. Moreover, there is no indication of any search for a suitable resident or EEC footballer.

‘We would welcome your comments on these aspects of the application and on any other relevant matter, including the question of understudying for Clemence.’

Luckily the Professional Football Negotiating Committee backed Liverpool’s application, answering the very next day:…in [the] opinion of the Professional Football Negotiating Committee the application from Liverpool meets the requirements of the work permit scheme. That wasn’t enough for the Department of Employment, who in a letter of 13 February 1981 wrote to the Football League: ‘As I mentioned to you over the telephone yesterday, we are not satisfied that the application made by Liverpool F.C. in respect of Bruce D. Grobbelaar meets the rules of the Work Permit Scheme.

‘Grobbelaar does not seem to meet our skills criteria; he has played only two international games for Zimbabwe — not a major football nation. Therefore, he can hardly be said to be an ‘established international player with significant contribution to make to the game’. Moreover he is required only as an understudy goalkeeper.

‘In addition, the club has not provided us with evidence of having made a search for suitable resident players.’

Luckily Bob Paisley got his way. The Department of Employment finally granted me a work permit in the UK, and I would start an unforgettable 13-year journey with a club and a city that hasn’t left my heart since.

On 15 March 1981, I came to Liverpool on a bet. Tom Saunders and Bob Paisley staked money against each other that I wouldn’t find my way to Anfield, or figure out what to do next. I didn’t know where I was going. I was a big signing of £250,000. That was quite a lot of money for a goalkeeper after only seeing a 20-minute warm-up, and one game that we lost in Vancouver against San Diego. So signing me was a big gamble.

I landed at Heathrow. They hadn’t given me a ticket to Liverpool; I had to find my own way from Heathrow to Anfield. I went via Manchester Airport by plane, hired a car, got into Liverpool city centre and did not have a clue where I was going.

I asked a black cab where Anfield was; he laughed ironically and replied, ‘Do I know where fucking Anfield is?!’ You don’t ask a cab driver that question in Liverpool without them laughing at you.

On arrival at Anfield. I realised the gates to the stadium were shut. It was 5:15pm, the working day was over, so I had to go and find a hotel. What did any person do when visiting Liverpool in the 1980s if they needed a room? They checked the Adelphi first. As I walked through the door towards the reception, I passed the lobby area, not taking any notice of the people sitting there. I asked the girl if they had any rooms and she apologised: fully booked.

As I turned around I saw Tom Saunders give Bob Paisley a £1 note, saying, ‘I never thought he would get here.’ One pound poorer, he gave me the keys and said, ‘Here’s your room for tonight, see you tomorrow at training.’

‘Life in a Jungle’ by Bruce Grobbelaar and Ragnhild Lund Ansnes is published by deCoubertin Books. More info here.