SHANE O’CONNOR CRINGES when he’s reminded of the tweet that created more headlines than his departure from Ipswich Town would otherwise have warranted.

It was February 2012, when Twitter wasn’t yet the ubiquitous force it is today. A social media novice at the time, O’Connor insists now that he was naively unaware of how many eyes would have access to his description of Ipswich manager Paul Jewell as a “c**t”.

“That wasn’t my finest hour,” he says through self-deprecating laughter. “It just blew up all of a sudden. I was in a bit of a panic because people were ringing me to get it down. I was so unfamiliar with Twitter that it took me a while to work out how to delete it.

“Ipswich had paid up the rest of my contract when I left, but part of the agreement was that I couldn’t say anything negative. It was a bit messy for a minute. Unfortunately if you Google me that’s probably still the first thing that comes up, which is frustrating because that kind of stuff isn’t who I am at all.”

Since leaving Ipswich, life has changed considerably for Shane O’Connor. He’s now a wiser man than the immature 21-year-old who fired a parting shot. But the intervening six-and-a-half years have taken him to some dark and difficult places. By his own admission, his plans to rediscover his best form elsewhere never threatened to come to fruition.

As recently as March, he was contemplating retirement. Still only 27, but his appetite for the game was waning. However, not for the first time, O’Connor soon found solace at a small club located 25 kilometres from where he was raised in Cork.

It’s only a matter of months since he convinced himself that he had nothing more to offer to football, and vice versa. Yet in next Sunday’s EA Sports Cup decider at Derry City’s Brandywell Stadium, O’Connor will lead Cobh Ramblers into their first ever senior national final.

The magnitude of the occasion may seem relatively meagre for a man who once played against Cesc Fabregas and Robin van Persie in front of 60,000 spectators in a semi-final of the English equivalent of the competition. But given the personal challenges he has since encountered, O’Connor is adamant that this game will mean more to him than any other.

***

Twelve months after their famous Champions League final victory over AC Milan in Istanbul, Liverpool signed a 16-year-old Shane O’Connor to their academy. Under the guidance of the likes of Dave Shannon and Steve Heighway, he spent three years on Merseyside after leaving the family home in Parklands on Cork’s northside.

By 2008 he was craving senior football, but a breakthrough appeared unlikely at one of Europe’s biggest clubs, where first-team opportunities for unproven youngsters are few and far between. That’s when his grandmother intervened.

“Myself and a fella I was living with in Liverpool were in the house playing Fifa and my phone rang,” O’Connor recalls. “When the call ended I told the other fella who it was. He was just like, ‘Roy Keane me hole, go on ya fucking liar!’ But it was.”

Hailing from the same neck of the woods as the former Republic of Ireland captain, O’Connor’s granny paid a visit to Keane’s mother and passed on her grandson’s number. Roy Keane, who was then manager of Sunderland, took it from there.

“He invited me up to his house one day for a chat,” explains O’Connor, who came through the ranks at Rockmount AFC, the same schoolboy club where Keane cut his teeth.

“By the time I went up he was gone from the Sunderland job. There was an Ireland Six Nations rugby game on TV, so we watched that and then had a game of snooker. He was even competitive in the snooker!

“We were just chatting about my own situation because at Liverpool I was at a stage where I was too old for the Youth Cup, and if I stayed I could have spent the next few years in the reserves, going nowhere. I wanted first-team football somewhere. He was just giving advice that day, but as it turned out he got the Ipswich job a couple of months later.

“I knew I wanted to leave Liverpool so I was getting trials set up as it was coming towards the end of the season. I sent him a text message and he told me to come in for a trial at Ipswich. I went in on the first day of their pre-season. After being there for one day, there was nowhere else I wanted to go. The trial went well and I got a contract.”

After assuring O’Connor that hard work would be rewarded with opportunities, Keane was true to his word. Once he recovered from a knee injury, the young left-back made 12 appearances in the Championship — 11 of them starts — in the second half of the season, which earned him a two-year contract extension.

“I remember when I was coming back from injury and a group of us were doing a bleep test,” says O’Connor. “Just as we were starting, the gaffer [Keane] came up to me and said ‘you better win this now’. All of a sudden I knew I had no choice but to win it — and I did, even though I wouldn’t have expected to at all. He just looked at me afterwards and nodded.

“It was just interesting because I still wasn’t 100% at the time, so I probably would have dropped out of it at some stage. Fellas will always look to get out of running drills. But the fact that he singled me out meant I had that extra drive to keep going. That was what he could do to get the best out of you. He’d put you to the test.

“With the gaffer like that, you either rose to his standards or you perished. He was always sound away from the pitch and he’d talk to you if you needed to go to him. But on the pitch, you had to do what he wanted or you’d end up at loggerheads.

“He was coming from a winning environment like Manchester United under Alex Ferguson, but that wasn’t the situation at Ipswich. He couldn’t understand how lads weren’t able to live up to those demands. People got the wrong end of the stick with him, I think. I was happy to put in the effort he wanted, although I got plenty of bollockings too.

“The problem with players is that a lot of them get the hump. I didn’t mind getting a scolding. He absolutely bollocked me in the dressing room for giving away a penalty one day. It lasted about 20 minutes. It certainly felt that long anyway. You wouldn’t dare answer him back either.

“It might sound harsh, but I did cost us three points at the end of the day. On the following Monday then it was forgotten. He’d smirk and say ‘right, let’s go again’. I could take it, I didn’t mind it. Some lads would just completely take a turn against him if he had a go at them.”

While O’Connor felt he thrived under Keane, his compatriot’s approach to management wasn’t universally popular in the dressing room at Portman Road. Keane was dismissed in January 2011, and it proved to be a major turning point for O’Connor.

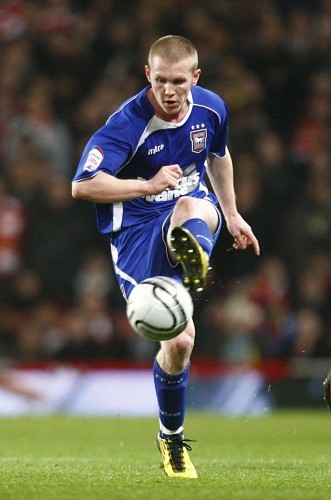

He played at the Emirates Stadium a fortnight later as Ipswich — then under the stewardship of Paul Jewell — lost a Carling Cup semi-final to Arsenal. Little did O’Connor know at the time that he’d never play a competitive game for the club again.

“When he [Keane] left, a lot of the lads were only short of going out for a party to celebrate,” O’Connor says. “Three or four of us were genuinely gutted, myself included. I really wanted him to succeed there. He was only missing a small few ingredients to be a success. He was hard done by, in my opinion.

“The bottom line is that no matter what line of work you’re in, your boss is going to get on your back if you’re not doing your job right. Some footballers think they have a divine right not to be given out to. They want a Harry Redknapp or an Ian Holloway who’ll put an arm around the shoulder and be one of the lads. That wasn’t Roy’s way.

“If you weren’t doing things right, he’d tell you, which is how it should be. He’d been to the highest level as a player and he wanted the players he was managing to get there too. That’s why I always enjoyed playing under him. You knew where you stood because he’d tell you straight out. I don’t have a bad word to say about him.”

He adds: “It’d be be fair to say that Paul Jewell and myself weren’t best friends. Only he knows what was behind it, but he wasn’t fond of me from the start. He sent me away to do extra sessions with lads that weren’t in the team and stuff like that. I just didn’t seem to fit.

“It probably did have something to do with my affiliation to Roy. In the first conversation we had he said, ‘I know you took it hard when the last gaffer left’. I told him honestly that Roy was my childhood hero and I enjoyed playing under him, so my card was probably marked then.”

Having been banished from the matchday squad for the remainder of the season, O’Connor weighed up his options in the summer of 2011. There was interest from elsewhere in the Championship and a deal was agreed with Doncaster Rovers manager Sean O’Driscoll. But with O’Connor still contracted to Ipswich, the club blocked the move.

“I thought I had the deal done but Ipswich wouldn’t let me join a rival team in the Championship, which I was really annoyed about. I wasn’t even getting near the bench at this stage. Instead I got sent out on loan to Port Vale, but even they didn’t want me.

“When I got there, I remember their manager, Micky Adams, actually asking me in what position I played. I couldn’t understand why I was there. I played a few reserve games and went back to Ipswich. At that point I was really starting to wonder where my career was going. Not getting a game for a mid-table League Two team, my head was starting to go.”

In January 2012, a year since he last appeared in Ipswich Town’s first-team, O’Connor and the club negotiated a mutual termination of his contract. An assessment of the lie of the land convinced the former Ireland U21 international that a temporary return home would be worthwhile. One step back in order to move two steps forward.

The signing of a local lad of his calibre was a significant coup for Cork City, who were about to embark on their first Premier Division campaign as a supporter-owned club. They called a press conference to show off their newest addition, who explained that he didn’t intend to stick around for very long. There was unfinished business back in England. The League of Ireland was merely a shop window.

City had great expectations of a player they managed to acquire in spite of the interest of several rival clubs. But when the time came for O’Connor to deliver, he struggled. He knew his confidence had been eroded by a year of being deemed surplus to requirements at Ipswich, but the psychological damage was far more substantial than he realised.

Spending six years within the bubble of professional football in England had conditioned him to a regimented lifestyle which revolved around his career in the game. Being back in the family home, cut adrift from the epicentre of his craft, was a culture shock for which he was ill-prepared.

“My head was gone,” he says. “I found it really hard. I shouldn’t really have had to come back because I had interest from Championship clubs which Ipswich got in the way of. I didn’t want to go down as far as League Two, and I didn’t have any options in League One.

“My confidence was just completely gone. People must have been looking at me, saying: ‘What’s going on with this fella? How did he manage to play in England?’ I just couldn’t handle being back home.

“I lost so much confidence that I no longer knew how to run past an opponent. I’d be up against a fella on the pitch and I’d actually be thinking, ‘I don’t even know what to do here’. I was so low that I thought there was no way I could make any meaningful contribution. You can’t blame the fans for giving me grief. They were paying my wages.

“I thought it would be easy when I came back. I should have been able to do what Richie Towell, Daryl Horgan and Seanie Maguire did a few years later. I believe I had the ability, but I didn’t have it inside me. When it came down to it, I didn’t believe I was capable.

“My confidence had started to dip at Ipswich. I remember hitting the post with an open goal in training, people were laughing, and obviously then my confidence was dropping. I was actually hiding from the ball on the pitch. I didn’t want it to come near me.”

O’Connor played four games for Cork City early in the 2012 season before injury problems sidelined him for a couple of months. An escape route then opened up in the summer. Sean O’Driscoll, who previously attempted to bring him to Doncaster, was appointed manager of Crawley Town and wanted O’Connor to join him there.

Having travelled to West Sussex to negotiate a deal, O’Connor went back to Cork for a few days to pack his bags before returning for a second crack at professional football in England. But there was a spanner in the works.

“I went out for a game of golf with my dad,” he recalls. “While we were on the course, I got a text from someone about Sean O’Driscoll, saying he was the favourite for the Nottingham Forest job. I thought it must have been a mistake because he was only after taking over at Crawley a few weeks earlier. Unfortunately it wasn’t.

“He went to Forest and Crawley obviously went in a different direction then, so they weren’t willing to uphold the contract that was agreed. I couldn’t believe what was after happening.”

O’Connor swapped Cork City for Shamrock Rovers with a view to making a fresh start, but little changed. He played three games for the Hoops and failed to make an impact as his off-the-field difficulties were manifested in his performances.

A downward spiral eventually brought him to rock bottom. After leaving Rovers, he didn’t play competitive football for a year. His family grew concerned for his mental health as he turned to gambling as a distraction from his reality.

“I had been playing professional football over in England for a long time. When I came home, the friends I grew up with weren’t there, the girlfriend I had in England was gone and my relationship with my family was becoming strained too. I was on my own. I found it very hard. It took a big chunk out of me.

“For a start, my love of the game went. When you’re over in England, football is your entire life. But when you come back home, all of a sudden you feel like you’re left with nothing.

“I was playing terribly. I mean, I genuinely believe I’ve lost about 50% of the ability I used to have. It was because I lost a bit of me inside and that was very hard to recapture. I had nothing else to rely on. I was depressed for a couple of years where I didn’t want to get out of bed.

“I should have handled it better. For years, football was the only thing I was good at, the only thing that could earn me a living. When I felt I was at a stage where I wasn’t good at it anymore, it left me in a bad place. I went to England at 16 so I had no Leaving Cert. Nothing.

“My mam used to come in from work at around 1 o’clock in the afternoon and I’d still be in bed. I couldn’t get up. I spent nearly all my time in my bedroom. Then there was the gambling as well. I was using things like that to take my mind away from football because I wasn’t able to deal with my situation.

“While I was gambling I wasn’t thinking about anything else, so that allowed me to switch off. It was a coping mechanism. If I had €20 in my pocket, my instinct was to gamble it to win more. When I was at Cork City I was on about €600 a week, I was living at home and I had no bills, but I was still always waiting for my next week’s wages.

“I have no idea what I lost on gambling over the years, which is probably a good thing because if I was told I’d probably get the fright of my life. That two or three years was a blur. I was still playing football but I shouldn’t have bothered. I offered nothing to any team.

“I was very fortunate in hindsight because a lot of families would have turned their back and I could have ended up on the streets. My mam and dad had every chance to do that with the way I was, but they stood by me. They dragged me back up. Without them, I really don’t know where I’d be.”

O’Connor had a brief stint with Portadown before joining Limerick midway through the 2014 season. He remains grateful to manager Martin Russell for providing him with an opportunity to “rediscover a hunger for football” during his time on Shannonside. The following year, things began to click again.

He linked up with Cobh Ramblers ahead of the 2015 campaign and played more than 50 games for the club over the course of two seasons. The left-sided marauder was transformed into a midfield general, as the support of Ramblers boss Stephen Henderson restored some confidence. Football gradually became a focal point again, helping O’Connor to relinquish his reliance on dangerous distractions.

“I mentioned how important my mam and dad were in getting me through the difficult days, but I could say the same about Hendo in Cobh,” he says. “Maybe there’s been some bad luck, but I’ve also been blessed to have had people who wanted to help me. I started to enjoy my football a lot more again at Cobh.

“People used to say I was mad to stay in the First Division, because there was interest from Premier Division clubs, but I was enjoying my football and that wasn’t something I could say since I was in England. Hendo gave me a bit of freedom to express myself in a new position, which stood to me. I loved it.”

An important part of the healing process for O’Connor was letting go of the dream of full-time football by accepting his need to look elsewhere for long-term career prospects. The lack of a second-level education, however, meant that was far from straightforward.

“It should be compulsory for young lads going over to play in England to do A-Levels [the UK's equivalent of the Leaving Cert] as well,” he says. “After I came home I missed out on a couple of jobs purely because I didn’t have a Leaving Cert.

“A large part of why I went into a depression was because of the fear of knowing that I had no Plan B. Football was my only plan. It’s getting even harder now too. I’d love to speak to any kid to help them with it, even when it comes to the kind of bullying that can go on over there too.

“In the first year at Liverpool I came home every month. I was homesick quite a lot. I stayed in a room with two other lads and they gave me an awful time. I remember them just firing shoes at me one night for their own entertainment. I was 16, I had only been there for about three weeks and I cried myself to sleep. Your family are away in a different country so there’s nothing they can do for you. You’re isolated.

“There’s a lot that young lads need to be ready for and they need to be supported along the way. I just think there’s a lot more we can do for young Irish lads going over to England. There needs to be a support network. They can’t be allowed to be on their own.”

O’Connor delivered another reminder of his ability when he joined Waterford for the 2017 season. The Blues achieved promotion back to the Premier Division for the first time in a decade and he was named the club’s player of the year at the end of the campaign.

Being chosen as the top performer in a talented squad was no mean feat, particularly in the context of how O’Connor was by now earning a living. After taking a job as a machinery operative at Dublin Port, his commitments as a footballer in Waterford had to be factored into what was often a 70-hour working week.

“We won the league, which was obviously great, but I didn’t even feel like I was playing that well,” he says. “I’d start work on the day of a game at 5am, finish at 2.30pm, drive to Waterford, play a game, drive back up to Dublin and then I was back into work the following morning. I was constantly wrecked. Because of that, I couldn’t honestly say I enjoyed it.”

With Waterford preparing to return to the top flight with a squad of full-time professionals, and O’Connor reluctant to give up his job in Dublin, he transferred to Longford Town at the beginning of this year. There, the workload finally began to take a toll he could no longer tolerate.

“I wasn’t sure if I actually wanted to play at all after Waterford. I was having fierce problems with my back as well. But Neale Fenn at Longford was brilliant with me. He convinced me to just give it a go.

“I only had to get the train to Leixlip, which took 20 minutes and it was much handier than driving down to Waterford. But straight away it seemed like an ordeal. I just wasn’t able for it, physically or mentally. I think I only played about four games.

“The last one ended up being against Shelbourne and I gave away a penalty. It wasn’t actually a penalty but I didn’t even bother arguing. I was just terrible. Afterwards I was like, ‘that’s me done now, definitely’. I was only 27 but I could barely move. I actually felt embarrassed on the pitch. I felt like I was costing the team points and making a fool of myself.

“I had a chat to Neale, explained that it wasn’t happening for me and I wasn’t enjoying it. In fairness to him, he could have gotten on my case but he understood where I was coming from. I didn’t want to give up, but I wasn’t able to give what he needed.”

Shortly after he parted company with Longford, a job opportunity materialised at home in Cork. Along with his partner Holly and her daughter Lily, O’Connor relocated back to Leeside to work as a courier for the HSE. A return to football wasn’t on the agenda… until his phone rang and a familiar number appeared on the screen.

“The move back to Cork was all about the job and setting up a life down here,” he explains. “But then I got a shout from Hendo. I probably wouldn’t have gone back playing for anyone else.”

Things haven’t gone according to plan for them in the league, but the 2018 season may yet end up a memorable one for Cobh Ramblers. With O’Connor wearing the captain’s armband in his third appearance since returning, Ramblers recorded one of the most significant wins in their history by defeating Dundalk in the semi-finals of the EA Sports Cup.

O’Connor: “Sometimes when you have an affiliation with somewhere, like I have with Cobh, it can make the difference. I’ve loved every minute of it since coming back. I’m blessed that Hendo gave me the opportunity, even if I wasn’t sure about it at first. He’s given me enjoyment from something I thought I’d never enjoy again, and I love him for that.

“That game against Dundalk meant more to me than anything I’ve experienced in football. I don’t mean to underestimate winning the league at Waterford, but I just love the place in Cobh. It’s the only place I want to be now. Since I came back, everything has kind of fallen into place for me — touch wood — from the job to the football.”

***

With just a week remaining until Cobh Ramblers travel to Derry for their biggest game in a decade, life is as good as it’s been for a long time for their captain. Although Shane O’Connor has endured some tough times over the years, a reshuffle of his personal priorities has granted him the ability to focus his attention on the good days on the horizon instead.

Football still matters, but his relationships with those closest to him, as well as the pursuit of a new career away from the game, are now at the forefront of his thoughts. While old wounds remain capable of causing pangs of regret, he understands that the road to recovery is a long-haul journey.

The key for O’Connor is knowing where to turn for support. Recognising the importance of not concealing his feelings, he opens up to the right people when help is needed.

For a brief moment he lived the dream he spent a long time chasing. That chapter may now be closed, but he’s enthused by the opportunity to open a new one. Furthering his education is one option under consideration. Whatever is next, he’ll attack it with the same determination he brought to Roy Keane’s bleep tests.

“The fact that I played first-team football at a high level against teams like Arsenal, I was at Liverpool, I played for Roy Keane… maybe in a few years I’ll look back and think: ‘Wow, that was unbelievable’. But I always felt like a failure, to be honest, and it’s something I’ve found very, very difficult to get over. It’s not yet something I can see as an achievement.

“People give out to me when I say it was a failure, but that’s just me being honest about how I see it. Even now when Ireland are playing or whatever, while I’m happy for the lads I know who are involved, it still grates because I feel like I had the potential to do that too. I’m not saying I’d have been a superstar, but I think I could have done enough to earn a decent living.

“The margin is slim and I came out on the wrong side of it. I could have done more. I should have done more. There was some bad luck, but I could have done a few things differently too. I left something behind me and that’s not an easy thing to come to terms with.

“When I came back from England for visits home when I was younger, I’d look forward to meeting people and having them ask how I was getting on. All of a sudden it becomes the hardest question, because no matter what the answer is, it’s going to be a come-down from what it used to be.

“When I was working up in Dublin, I didn’t tell the other lads in the job anything about where I came from. But people eventually found out and they’d ask: ‘How the hell did you end up working here?’ I don’t think they mean to do it but you end up not feeling great about it.

“There were times when I was working on Saturday mornings, and I’d be thinking to myself that not so long ago at this time on a Saturday I’d be getting ready for a game. I know it might sound silly, but small things like that can be hard.

“But that’s one of the great things about Cobh. People there only talk to me about Ramblers. There’s no talk about what I’ve done before. I love that. It makes me feel at home. They know me for who I am now, not who I was. What happened before is irrelevant at this stage.

“My girlfriend has been so important too. She’s gone above and beyond to make sure I don’t go down a bad road. She helped me to find a meaning to life beyond football.

“Having said that, I’m still absolutely buzzing about this cup final. We’re a part-time side going up to play against a really good team of full-time professionals. It’s on a Sunday, so on the Monday morning their players will all be able to recover. We’ll have a long journey back down to Cork and we’ll be back into work. Although if we win there might be a few lads calling in sick.

“Dundalk took us for granted. If Derry do the same then hopefully we can give them a rattle. But I certainly believe we have a chance either way.

“If we win this it will mean more to me than words can explain. I honestly didn’t believe I’d ever have something like this to look forward to again, so I’m going to enjoy every bit of it.”

The42 is on Instagram! Tap the button below on your phone to follow us!