THE BOAT’S ENGINE exploded as they were navigating the Suez Canal, unexpectedly interrupting the journey from Belfast to Melbourne. For the Magees, it was an early indication that their world was about to be turned upside down. A first jolt in the oncoming storm.

Australia in 1952 was a strange place. Just getting there proved a significant ordeal. To this day Stuart Magee does not know the name of the country they were stranded in for two weeks while repairs were conducted. He was only eight years old when he, his mother, father, brother and sister packed their bags and set sail.

Eventually they landed in Williamstown, the beginning of a remarkable journey to the top of Australia’s game.

“When I first went to school I got some surprise. They weren’t kicking soccer balls. It was this oval thing,” he recalls with a hearty laugh.

“I came home to Dad and said, ‘you’ll never believe it! They are kicking a ball that is oval shaped. What are they doing?’

“Eventually when I played my first game, they asked me can I kick the ball. I said ‘yeah, of course’ and kicked it as normal. The laughs that got. ‘That is not a kick!’

“I couldn’t do it their way. They had to teach me, in those days there was a drop kick. That was all new to me.”

He would go on to master it, amassing 216 appearances for South Melbourne and Footscray, now known as Sydney Swans and Western Bulldogs.

There were no grand ambitions behind Alec and Annie Magee’s decision to emigrate from Shankill Road. All they ever wanted to do was get by. That proved difficult in mid-20th century Northern Ireland. Becoming one of the Ten Pound migrants offered rescue.

The post-war scheme was designed to attract workers for Australia’s booming industries. Sometimes referred to as “Ten Pound Pom”, in actuality it was not limited to migrants from the United Kingdom but any classified as a British subject.

- For more great storytelling and analysis from our award-winning journalists, join the club at The42 Membership today. Click here to find out more >

The Magees landed and lived in the port settlement of Williamstown. For four years they lived in a hostel surrounded by a melting pot of migrants.

“We got off the boat and went straight to the hostel. Two rooms for the five of us. You go out the door and walk 300 metres down the road to go to the toilet and shower. The canteen was up and around the corner.”

It wasn’t much but it was a start and an upgrade. Over the years, Magee has made return trips to Belfast and visited their old one-unit home. Two beds and a small space to cook. Incremental, steady progress would become the family habit.

His father got a job with a motor company in Port Melbourne and began to save money. Stuart immersed himself with the neighbours and began to play ball.

“Back then it was mainly British, us Irish, Greeks and Italians. When you are in a hostel, you don’t notice really. Italian, British, who cares? All you want is someone to play with.”

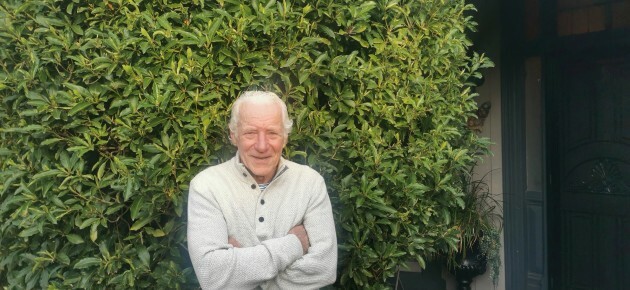

It never took much to make Stuart content. A preference for the simple things that he carries still. He sits back in his Bayside home and smiles; it has served him well so far. The house is well over 100 years old, and he takes pride in its upkeep. The front porch still bears evidence of his morning endeavour. Fixing gutters, redoing paint and relaying a garden step.

He has an old mobile phone and never uses it. Friends and family know the only way of contacting him is through his wife, Vicki. “Old-school,” he chuckles. Always a buttoned-down old pro.

Magee made his way thanks to a ravenous work ethic. It is renowned and routinely referenced by team-mates. To this day, an absolute fitness fanatic. A daily diet of sit-ups and 5km runs.

His disinclination for technology means the back door is the typical starting point. A quick glance at the wooden clock hanging on the wall and away he goes. The kitchen table operates as a finishing post where he can check if he has set a new record.

The odd piece of advice and a coach’s comment helped, yet the source of this appetite for work sprang from soil so much richer. Forged by family and upbringing. Magee’s father continued to graft and got a job delivering gas bottles for the gas and fuel corporation. After four years in the country, he saved enough to buy a family home in Altona.

That was where Stuart found Aussie Rules. When he kicked six goals in a local league game against Weribee, three-time Brownlow winner and South Melbourne rover Bob Skilton happened to be in the crowd.

“I got a letter from the club to play with the U19s. The trouble is I worked in Newport. I had to get to South Melbourne. I had just turned 17 and didn’t have a car. So, I would run to Newport railway station, catch the train to Flinders Street in the city. Change there to South Melbourne and run from that station to the ground.

“At the time, I worked for McKenzie and Holland as an electrical fitter. My dad got me the job. I did all the electrical work and went to night school one evening a week from 5 to 9.

“The boss of that company was a massive South Melbourne supporter. He didn’t know me or anything about my football. I was playing with the U19s until all of a sudden, there is a big thing in the paper, ‘Magee stars in his first game.’ On Monday I walk into work and hear a shout, ‘Stuart! In here to my office.’ I was thinking, ‘jeez. What did I do?’ The boss grabs me and says ‘Stuey! How good is that. You are playing for us.’

“He managed the company, over 500 workers. We had an arrangement; every Monday I’d go in and have a cup of coffee with him and chat about the weekend’s game. When I turned 20, he gave me a company car and made me a salesman. He said, ‘everyone will know you. It suits us both.’

“I had to go to customers, and they’d only ask about footy. He was smart and I was lucky.”

PIC

Now it is Gaelic football that helps Irish prospects make their unique mark on the AFL. The ‘Irish experiment’ stretches from Jim Stynes to Mark O’Connor, decades of remarkable transitions to the top of a foreign professional sport. That is a considerable part of the Irish story in the AFL. Not the whole.

Beneath that lies the emigrants. Exiles often forced or pushed abroad by economic constraints. Their story is lesser known but is as rich and varied. Tales of triumph and success in the face of great odds. It includes the likes of North Melbourne defender Aidan Corr, who played in the 2019 Premiership final. His family left Tyrone when he was a child.

Three-time Premiership winner Liam Shiels is the son of a Donegal man. They will not be the last of the Irish diaspora to excel Down Under. After all, Magee was by no means the first. The history of the VFL/AFL is intertwined with the history of Irish emigration. It often crops up in old chronicles and trivia. Who is the first player to compete for three clubs? Tipperary’s Denis Lanigan, who played in the 1890s.

Magee never sought the limelight in Ireland or Australia. Not until 2020, when he opened the paper to read about Portlaoise native Zach Tuohy and his outstanding achievement. Something about it was hard to swallow.

“I guess no one really knew I was Irish. Not the opposition, not my team-mates. Then when he played 200 games, all the papers here said, ‘the second Irishman after Jim Stynes to reach that milestone.’ We got the paper here and I was looking at it thinking, ‘I came over in a boat. I lived in a hostel, and we put up with some of the worst things. I travelled all over Melbourne to play. Do I not count?’

“What happened to me? That is why I rang the bloke from the paper. I said, ‘my name is Stuart Magee, I was born in Belfast in 1952. I travelled to Australia and played for South Melbourne. I captained the Western Bulldogs. I played 216 games.’ Never heard from him again.”

Not that his background was ever a hindrance when his two worlds collided. In fact, tactically, it was a distinctive benefit.

“Soccer was the best thing for me. I played centre half forward, covering a lot of ground and chasing the ball when it went long. Back then in Australian Rules, a full forward would stand in his spot, half forwards stayed.

“Wings only out there. You always stayed in your area. If you are half forward flank, you did not go into the centre. They’d shout at you to get out of there. But I played soccer and would chase everywhere.

“That is what I was good at. When I played with Altona, they all used to say, ‘what are you doing? Stay in your position.’ One coach saw me taking marks and running around. He just said keep playing like that. Go wherever you want. I did that for my career.”

Magee progressed seamlessly to the seniors. The club had been a powerhouse and won three VFL premierships between 1909 and 1933. After that rise came a fall. South Melbourne was marred by financial troubles, poor form and various petty politics.

He got caught in the crossfire.

The Belfast native enjoyed a six-year stint despite their slide. This chaotic era would lay the groundwork for their move to Sydney and rebrand as the Swans.

PIC

The end came suddenly. Prematurely. The club appointed a new coach heading into 1967 and opened the season with a six-game losing streak. A senior players meeting was called and Magee was asked for his input. Having worked with the same coach at underage level, he merely recounted his own experience. The training was the exact same. Copy and paste from the U19s to the seniors. They needed more sophistication.

That meeting took place on a Saturday night. Word got back to management the next morning. He was sacked by Sunday evening. A week later, the rover moved on and joined Footscray. Standard operating procedure for a man who thrives in the fast lane. The mantra was well-established; don’t dwell on the past. Keep moving forward.

Several clubs in the AFL are intrinsically linked with religious foundations. That moulds their present and future. Essendon were associated with the prosperous and Protestants. Richmond had a reputation as a Catholic outfit.

Footscray was once proletariat Protestantism but by the time Magee made his move, a secular faith had taken hold.

“They were the workers. Footscray in the ’70s was a different spot to what it is now.”

Joining a trade union was heavily encouraged. Players who crossed picket lines were banished. The club has its creed. It also had a folk hero. ‘Mr. Football’, Ted Whitten, an inaugural hall of famer and captain on the AFL team of the century.

Whitten was idolised in the western suburbs and he saw something in Magee. They shared a discipline and a purpose. He was unwilling to watch the club struggle; the Irishman was hardwired the same way.

“I went to the right place at the right time. My work was down the road in the factory. It was so lucky. Whitten told me at the beginning of the year, ‘if you are having problems with someone let me know and I’ll knock them out.’

“He came to me in 1970 and said, ‘Stuey. I have bad news and good news. The bad news is I am retiring. The good is that you are going to be the new captain.”

As soon as he landed, Magee wanted to create a new reality. Coach Charlie Sutton was a willing facilitator. An embodiment of the club’s fighting spirit who won a Premiership during his own playing days.

Change could come if there was total commitment. Professionalism was on the horizon, for Footscray it was scarcely discernible. They trained two days a week, Magee pushed Sutton to make it three. In training they ran two laps of the paddock; Magee would often clock ten.

Captaincy added legitimacy to his constant push for a higher benchmark. In 1969, the club finished second bottom with only six wins. In 1970, they shot up to seventh and won the Night Premiership, a competition for the clubs who finished outside the top four.

They would falter in the subsequent years. It culminated in the late 1980s when their financial position was deemed terminal and a contentious merger was arranged. Lively protests and fan-led funding initiatives forced authorities into a late intervention and the Footscray-Fitzroy union was cancelled.

As sad as it was to witness, none of the trouble came as a surprise to Magee. He saw first-hand the seeds of poor practices sown. It would eventually cost him the captaincy.

Alarm bells started to ring when he was invited to a club event at Flemington racecourse in his role as captain. Only one other player was in attendance, the vice-captain. The rest were strangers, introduced as friends of an influential board member.

Who is paying for this party, he wondered? How is it helping the club?

Towards the end of the season, the players came to him with a problem. Thanks to his fulltime job, money was never a pressing concern. His parents’ principles ensured he would never pry into what a colleague earned.

When they told him of their paltry salaries, he was appalled. It could not be tolerated and was contrary to what the club was supposed to stand for.

“I went into the boardroom and said it outright, ‘this is ridiculous. He deserves five times that. Either they get a raise or we don’t play on Saturday.

“’If you don’t pay them, we aren’t playing.’ They started shouting, ‘you can’t do that to us.’ I just said, ‘you are doing it to them.’

“Eventually they came down and made an offer, which wasn’t bad. It gave them something. I spoke to the lads and they were happy with that.”

The group gathered collectively and were told of the new agreement. As it came to an end, Magee felt a tug at his elbow and a whisper in his ear:

“’You are fucking finished at the end of the year. You like that? You try fix us up, we’ll fix you.’

“Anyway, the season finishes and we turn up for preseason. Everyone is in the clubroom as they are introducing the new players. Then they stand up and announce the new captain, Gary Dempsey. He came over to me and couldn’t believe it. That’s how league football went back then. That’s how they could treat you. Just like that.”

That is now a distance realm. Player welfare has drastically improved and the club, now known as the Western Bulldogs, make a meaningful effort to incorporate past alumni which Magee hugely appreciates. There are weekly breakfasts for past and current footballers. An active old players association and free tickets for home games.

The game takes and it gives. Economics brought the Magees to Australia. Fatefully, football brought him back to Ireland. In 1967, an elite Australian team travelled to Dublin to take on All-Ireland champions Meath in Croke Park. This was the genesis of the International Rules series.

It was organised by former broadcaster and umpire Harry Beitzel after he caught a glimpse of the All-Ireland final on television. Christened ‘The Football World Tour’, a star-studded squad visited Ireland, the UK and the US.

The trip was self-funded, several players did not have passports and had never left Victoria. Bietzel knew they needed publicity to make it viable. A touring team needed a touring uniform, so he dressed them in slouch hats, invoking memories of the regalia worn by soldiers in World War I.

They were widely pilloried. Players once again proving easy targets.

Criticism came from the floor of the parliament. Current affairs programme This Day Tonight read out letters labelling the team ‘ratbags.’ One particularly vocal critic decried them as ‘galahs’, an Australian derogatory slang term.

Beitzel co-opted the title. They became known as ‘The Galahs’. A simple uniform selection spawned weeks and weeks of media coverage.

“I played against all these legends in the league. Normy Brown, Ron Barassi, Ian Law, they were the greats. Neville Crowe! I was only invited because of Graeme Chalmers. He was with Footscray as well at the time.

“He said to me after he heard about it, ‘hang on where are you from?’ Ireland! So, Harry Beitzel rang me afterwards. After we landed in Ireland, we went from Dublin up to Belfast. I went on TV as the only Irishman to make it. That’s the only reason I was picked really, he wanted the publicity.”

Local Irish emigrants ran the training camp in Melbourne. He chortles at the memory of VFL icons trying to kick and solo the round ball.

They played a practise match in the Northern Territory before departing. The sudden move from Australia’s sweltering October temperature proved a challenge.

“We only did a punt kick. The thing was, we were way fitter. We got an idea how they trained and they weren’t very fit. The only reason we won was because we could run and run.

“We played a game up in Darwin first. It was just a bit of fun really. Then we went from there to Dublin and Crystal Palace. Boy, was that one extreme to another.”

Magee did not play in game when they beat the 1967 champions Meath in Croke Park. Victories over Mayo and a ‘Britain’ team made up of expatriates and touring Galahs followed.

The tour was bookended by a bloodbath in New York. Smashed jaws, broken noses, no hard feelings.

“They boasted about it afterwards. ‘You know how we beat you? We literally beat you.’

“They were on the police force so they knew how to handle themselves. It was a different time then. Even the guy who hit Barassi, they became great friends. He used to fly over here and everything.”

A minor blimp on the trip of a lifetime.

When his playing career came to an end, Magee did some post-game punditry and boundary work with ABC. He tried his hand at coaching out west in Perth but it never stuck. For a decade his unyielding standards were the making of him. There was pure incomprehension, he confesses, when others could not offer similar.

Stuart Magee is not one for reminiscence and reflection. In his era, it wasn’t an option. Stop and smell the roses and you could be hit by the train.

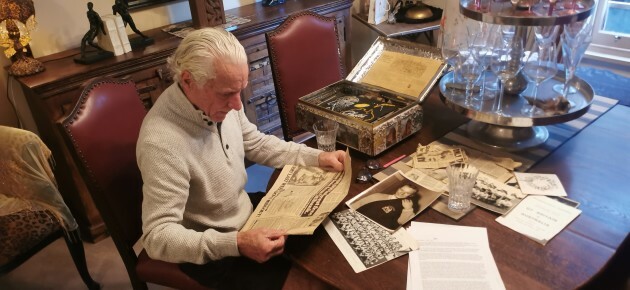

Even still, his wife maintains meticulous records and newspaper cuttings charting his rise and legacy. Cracking open that box for this interview unleashes a wave of nostalgia. Often, he pauses over a photograph and recounts a distant memory. Breaking off to point out his father’s moustache or first pair of boots.

How does he feel about it all now? Content, utterly and ultimately.

“I retired at the right time. I knew I had enough. I was done in the end. When you know, you know.

“14 years plus one underage, 15 years. What more can you ask for? Now some of them go longer. In my day, 14 years was a long career. Bobby Skilton played 230. Ted Whitten’s 300 was massive. Now they are getting 400!

“I’ll tell you a good one. Even when I went over to Perth to coach, McKenzie and Holland had an agent over there and got me in. They bought me a Fiat sportscar. How lucky can you be? The manager called me and said can you start work on Monday? I said ‘sure, I can start whenever you want.’ I walked in and my car was there. I was so lucky mate. Pure luck and a bit of hard work.

“I’ve had it good, have I ever! For a kid who came on a boat, started with soccer, played for Victoria and went from there.

“I’ve had a great time.”

For more great storytelling and analysis from our award-winning journalists, join the club at The42 Membership today. Click here to find out more >