PROFESSOR PHIL SCRATON, a leading member of the Hillsborough Independent Panel, believes that the true cost of the tragedy is “unquantifiable” and that its ramifications still “eat away” at victims’ families more than 25 years on.

The Merseyside-born professor was part of the panel established by the British government, which was tasked with examining documents relating to the disaster. Its report led to a government apology, new inquests and criminal investigations into the disaster.

The Professor of Criminology at Queen’s University, and author of the acclaimed book Hillsborough: The Truth, has emphasised the hardships that the families of those involved are still being put through, following the death of 96 people and injury of many others as a result of a human crush during the FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest on 15 April, 1989.

“Many people experience sudden death and they experience tragic death in their lives,” he said. “My own parents died very young and my children never knew their grandparents. And it was tragic the way they died. But there was no cloud or injustice over it. I can still talk fondly about them and I’m not in the public eye over it. The whole thing’s not being trawled through again. The reputation of the person who died isn’t being dragged through the mud.

“When you get Daniel Spearritt, who was not born at the time, his father Eddie who died two years ago and was never able to work again and whose [other] son died in his arms [at Hillsborough]… And Daniel’s a lovely young guy, so Eddie and Jan have done a wonderful job. But it’s always despite Hillsborough. It’s always ‘we’re going to the next meeting, we’re in the media again.’ Another film. Another book. Another whatever.

“Living with Hillsborough is like living with any unresolved issue — it eats away. The families are incredibly generous. They’ll say things like ‘I’ve become a stronger person because of Hillsborough,’ but you want to become a stronger person in a different way.”

Professor Scraton also speaks of how the victims’ families must continually face up to the difficult realities of Hillsborough, amid the ongoing investigations and various developments in the case.

“I remember they came to Queen’s University when we showed them Jimmy McGovern’s film about Hillsborough. The people who had been there were devastated by the film. We went for something to eat and drink after, and all the Hillsborough victims’ families were sitting there with Jimmy and they were laughing. People I worked with or people I know were distraught and they wanted to say something to them, but they said: ‘I don’t feel I can, I’ll just cry.’ Somebody asked: ‘How come it didn’t affect them?’ If they responded outwardly the way they feel inwardly, they wouldn’t be able to sit through it. They’ll cry in the dark throughout that film and they’ll cry when they go home. But for now, they’re trying to normalise their experiences.”

(Warning: this video contains distressing scenes)

Having spent many years investigating and undertaking research into the disaster, Professor Scraton says that the true impact of the tragedy is impossible to judge.

“I can’t tell you how many people have died because of Hillsborough. People have taken their own lives. [There have been] premature deaths after the onset of Alzheimer’s. I can give you a list of a whole range of illnesses. People dying young. Survivors dying young. Survivors taking their own lives. The real cost of Hillsborough is not quantifiable — and if you add the traumatising effects, it’s certainly not quantifiable.

“I saw real relief [from the families] when we produced that report. They applauded the panel for five minutes. And now going through the inquests, I’m spending half of my time in tears, because I’m seeing what it’s doing to them all over again. And that’s the price.”

Professor Scraton described how the tragedy has had a significant emotional impact on his own life, but emphasised the importance of retaining a distance from it.

“The most important issue for a researcher is to know where to draw that line and not to write under severe emotion. You have to stand back and you have to be able to formulate your argument. You can’t use the emotional words that you might use in a conversation.

“What you have to be careful of is vicarious trauma — that you don’t start to live the lives of others — that isn’t my life and I’m very fortunate it’s not.”

He describes the exhaustive research that being part of the Independent Panel required him to undertake, and criticised the media’s handling of the tragedy in the years since its occurrence.

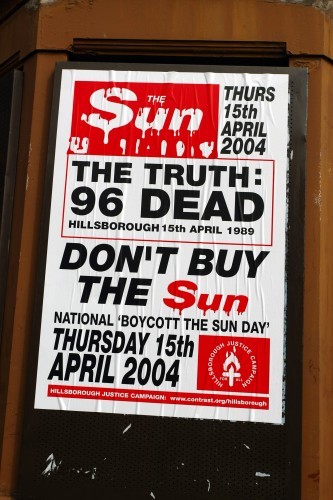

“They kind of remained silent because the upsurge was so great against them at that moment,” he said. “Even when I published Hillsborough: The Truth and The Mirror ran a serialisation — even at that moment, the other newspapers remained silent. I think it’s indicative of the power within the media. We have to remember that The Sun has never recovered on Merseyside — they still estimate 10,000 copies a day is their shortfall within the region. They’ll never be forgiven. But I think the media was complicit in its silence.

(A poster outside Anfield urges people not to buy The Sun newspaper on the anniversary of the Hillsborough disaster due to its coverage at the time)

“Even years afterwards, when I was trying to interest the media in the stories I was discovering — and I’m usually pretty persuasive — there was a real reluctance to run them.

“1989 was a crucial moment in Thatcher’s government. The connections you had between the Thatcher government and the media were absolutely profound. It was The Sun that stopped Kinnock being elected and it was The Sun that helped to elect Blair. We know that this was how the media was operating.

“I think the media ran scared of Thatcher and her power. We saw it in the coal dispute, we saw it with the Falklands War and a whole range of other issues. So the media was at a very dicey moment. Now of course, the media is falling over itself to give each other awards for all the latest [Hillsborough] revelations. But it’s been a long haul to make that switch.”

(Hillsborough Independent Panel member Professor Phil Scraton pictured during a press conference at Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral in 2o12)

Professor Scraton also recalls how, from a young age, he has learned never to blindly trust authority — a key motivating factor in his efforts to help expose the systemic corruption at the heart of the Hillsborough disaster.

“We were in assembly and we were just going through the normal routine. The head teacher, deputy head teacher and parish priest were on the stage. This blessed trinity of men were all there, and I wasn’t sure why they were all there because it’d usually just be the deputy head. At the end of the assembly, the teacher asked all the girls to leave — and this was totally unprecedented. He told us to sit on the floor and we sat on the floor cross-legged. And it was silent because we didn’t know what was happening. I heard this crash behind me and I felt so intimidated I couldn’t look around. It was the doors. In walked two of our male teachers — very tall — and they walked right down the middle of us, and in between them was Frank Ruddy.

“Frank Ruddy was very small for his age and a lot of the kids would call him ‘smelly Frank’ — he was from a very poor family. And he was taken onto the stage. The head teacher said there had been numerous thefts from one of the local corner shops, and it had been discovered that Frank was the culprit. Frank had been stealing biscuits — children don’t usually steal biscuits, they steal sweets or something else. Frank had been stealing biscuits because he was hungry and his brothers and sisters were hungry. He was stealing to live.

“He was told in no uncertain terms that he’d let himself down, he’d let his family down, he’d let the school down, but most of all, he’d let God down. The teacher took his hand and he caned him — six times on his right hand, six times on his left hand, and then he bent him over the table, and caned him six times on his backside. I was doing everything I could not to wet myself, I was so frightened. These men, who I saw every day. This priest, who I would serve mass for at 7 o’clock every morning. They were all party to what we would now call cruel and unusual punishment.

“As Frank was led off the stage, his face hadn’t changed, but there were tears dripping from both sides of his cheeks. That was the moment that I decided I would never ever trust authority again.”

Professor Scraton was speaking at a public lecture in Trinity organised by Children’s Research Centre in association with the Structured PhD in Child and Youth Research.

A version of this post was originally published on 9 May, 2014