IT IS TUESDAY lunchtime and Jeremy Davidson is beginning to feel a little like Andy Dufresne, the lifer in The Shawshank Redemption.

Just over two weeks have passed since he and the rest of French society were placed under house arrest and while the initial release from the grind of a Top 14 season felt liberating, the onset of a life without sport has started to grate.

There is a new rhythm and routine to his week. Instead of rising at 5am on a Monday, getting into work for 5.30am, leaving at 8pm, Davidson’s commute now involves a stroll down the corridor from his bedroom to a makeshift office.

His days as Brive’s head coach remain busy, even if technically he – and the rest of his staff and squad are on partial unemployment, paid 70 per cent of their net wages by the French government while this Coronavirus crisis unfolds.

Legislation prevents him from demanding anything from his players right now. Instead, everything he does is a request, a plea for them to take photos of their meals, to send in daily photographic evidence of their weight measurements, to partake in video conference calls, to continue their running and weight programmes.

“We emptied the gym of all the equipment and machines just before the lockdown, transporting all the various stuff to players’ homes,” Davidson says. “Sure, this is a difficult time but logistically, we’re doing whatever we can to get by. Every club is in the same situation as us. You get on with it. You can’t feel sorry for yourself.”

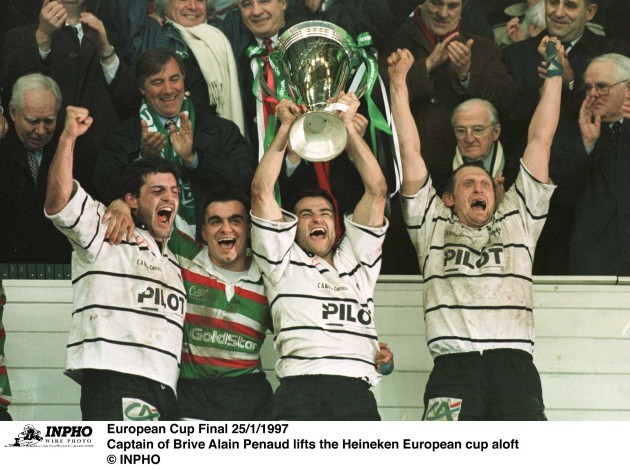

Not in this town, you can’t. You feel the history everywhere you go here, this being the first French town to liberate itself from Nazi rule in 1944, the second French club to win the Heineken Cup some 53 years later. Reminders of both moments are visible, posters of the liberation in local cafés, pictures of the ’97 Cup win in Davidson’s office. “There isn’t a week goes by when someone doesn’t nostalgically reflect on ’97,” Davidson says.

“Like, you don’t feel smothered by that. You can go about your daily business as normal, the difference is you might come across Alain Penaud or one of the other ’97 team-members who still live in the town. Certainly, you sense the responsibility when you see 14,000 people turn out for a home game – roughly a third of the town’s population. They live for their rugby, their town. Personally, I love the pressure that comes from that.”

There is a different kind of pressure now. In the Davidson house, there are no placards of famous faces and honours, 1997 Heineken Cup wins, or references to the club’s four trips to French championship finals. Instead there are just pictures of the princesses his daughter, Ruby, looks up to.

She’s approaching three, nearly half of her life spent in this rugby town, which has consumed her daddy’s waking hours. Monday may be his longest day, video reviews in the morning followed by training and then a board meeting with club directors, but Tuesdays and Thursdays are also 12-hour working days.

Wednesdays are kinder. He works eight-to-one before an afternoon off precedes evening meetings with agents. Having a sharp eye for talent is the reason Davidson is still in this profession, 17 years after a knee injury ended his playing career.

These last two weeks are the first time he has been technically out of a job – even though he has still been putting the hours in, analysing Brive’s 17 games in this season’s Top 14, the seven wins, one draw and nine defeats. “I’d say I’ve seen each game at least seven or eight times,” he says. “There’s always something that you spot.”

When he’s not watching this year’s Brive side, he’s trying to figure out who’ll be on next year’s team, using up whatever spare time he has to pore over videos of lower league French games and provincial rugby in Australia and New Zealand. “You can talk as much as you want about culture and work ethic but unless you recruit the right type of character, you won’t get that,” Davidson says, hence these marathon video sessions, and long-distance phone calls to contacts and coaches he knows throughout the world.

There are 13 different nationalities in his dressing-room, including Irishmen Stuart Olding and Rory Scholes, the majority of whom helped Brive win promotion in Davidson’s first year and get off to a fine start in this, his second season. “When it goes well, you feel it around the whole town. Everyone approaches you, asking, ‘well Jeremy, how’s things?’ You lose badly, though, like we did at home to Racing just before Christmas, and you don’t want to leave the house for a week. You don’t want anyone to see you.”

This sense of invisibility is nothing new. For years now, several Irish coaches have felt unnoticed, seeing England’s 2015 World Cup staff emerge, one by one, into the IRFU’s system, while New Zealanders, Australians and South Africans have, at various stages, migrated to head coaching roles in the four provinces. “Jobs in Ireland are hard come by,” Davidson says – pointing out his dream is to return home and become Ulster head coach, something his two sons would love. “If I ever get a job back home, I’d like it to be when I’m ready, at the peak of my career,” he says. “I’d hate to return and not do a good job.”

They don’t use words like that either in Brive or Aurillac, the low-budget French D2 side who Davidson rebuilt, realising from the start how French clubs are ‘prone to waste’. After eight years there, he moved on, working as forwards coach at Bordeaux-Begles, a stop-gap role until Brive’s call came.

His task is to make these former European champions great again. Two-thirds through the season, they now stand 10th - eight points off the play-off places, seven points clear of relegation. “Year one was about promotion, year two about survival, year three about getting to the top six,” Davidson says.

They were on track. Then came Covid-19, the shutdown and his new reality. “During the season you’re always on the go. Fridays often are match days so Saturdays and Sundays are busy, doing reviews, watching other games. You’re never off.”

He still isn’t. But try telling Ruby that. She doesn’t understand this life her daddy has. Nor does she know he was a titanic force on the 1997 British and Irish Lions tour to South Africa, winner of 32 caps for Ireland, an accidental coach. “My first night coaching, way back all those years ago at Dungannon, began at 6.30pm. Next time I looked at my watch, it had just gone nine. I felt invigorated. ‘This is for me’, I kind of said to myself. I wouldn’t swap this job for anything.”

Someday the choice will not be his, as the gap between success and failure offers little shade in professional sport. It’s a brutal business at the top end of the Top 14, months of sweat often condensed to a single match.

Yet there’s context needed, too. “People are dying through this rotten illness, people are ill. I just won’t hear that we have it hard. We don’t, for goodness sake. We’re privileged people and even if we’re a little frustrated at the moment, it’ll pass. We’ll still have our rugby and still have our health.”

And their passion.

Originally published at 16.23