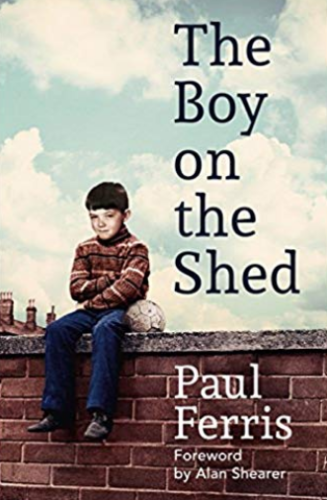

THE FOLLOWING PASSAGE is an extract from ‘The Boy on the Shed’ by Paul Ferris.

As results deteriorated and the atmosphere at the training ground became ever more toxic I invited Alan Shearer to my local pub to spend an evening in the company of Ruud Gully’s assistant, Steve Clarke. I hoped a few pints in the quiet country pub would help ease the growing tensions that were all too evident and affecting everyday life at the club.

We had a great night. They got on well, aired their differences and shared lots in common.

When my drunken head hit the pillow I was satisfied that things would change after the meeting. I was happy that I’d made a small contribution towards restoring some

sanity. I was confident things couldn’t stay the same at the club after this meeting had taken place between the club’s best player and Ruud’s right-hand man. And change they did. Just not in the way I’d imagined.

If anything, in the weeks and months that followed the mood in and around the training ground plummeted. The fissures became cracks, and the cracks developed into one giant fracture. The club was broken. If I was in any doubt as to what side of the fracture I was perceived to be on, then Derek Wright clarified matters for me.

‘I need to speak with you in private, Paul.’

Derek’s expression suggested it wasn’t good news he wanted to share with me. I followed him into the tiny cupboard adjacent to our treatment room.

‘I’ve been asked to distance myself from you. The perception is that you are too close to Alan.’

I slumped down on to a box of strappings and tried to fathom what exactly I’d done wrong. My loyalty had always been to Newcastle United. I regarded myself as an employee who could always be relied on to give my very best to whatever task I was

asked to perform. If I was close to Alan that was only because I’d put my heart and soul into getting him fit from a career threatening injury. It was a natural by-product of that effort and commitment that we would develop a friendship based on trust and respect.

That friendship didn’t automatically make me the enemy of the manager. I was capable of forming my own opinions about the mess the club was in. I certainly wasn’t interested in taking sides in any arguments. If anything I’d tried to bring the two factions of a divided dressing room together in the hope of uniting them and making Newcastle United stronger for it.

How could that be anything other than a good thing to do? How could my actions be interpreted in any other way? My attempts to help the situation had backfired spectacularly on me. I was now perceived as Alan’s friend and that was not a good place to be in those cancerous times at the club. I wanted to go and speak with the manager. Tell him how disgusted I felt about the situation. Derek stopped me from making matters much worse for myself. Instead I sat in the cupboard until my pulse had settled and my anger had turned to disdain. I was grateful for Derek’s decency and loyalty. I stored the information and got on with doing the job I was being paid to do. I had a mortgage and bills to pay; I couldn’t afford to lose my job.

Managers and players could come and go. They could love each other or hate each other. They did so with enormous salaries and bank balances to fall back on. The money that was pouring into football in the 1990s was hitting a dam before getting anywhere near the medical department. I hated that my future could be decided on a whim. It felt unjust and unnecessary. I began to dread going to work.

‘When Alan Shearer and Rob Lee speak in the treatment room, you don’t answer.’

Ruud was sitting opposite me in the cramped changing room at our latest training base in Chester-le-Street. I looked up from tying my laces. He was smiling. There was no malice in what he was saying to me. There was also no sense in what he was saying to me.

‘I don’t know what you mean.’

He was on his feet now and walking out of the door, his short dreadlocks bouncing in rhythm as he strode past me.

‘That’s all I’m saying. When Alan Shearer and Robert Lee speak in the treatment room, you don’t answer. See you later, lovely boy.’

And with that he exited and left me a little puzzled. I spoke with Derek and I managed to confuse him too. Late that afternoon as I was leaving the training ground, the receptionist stopped me at the front door.

She was sorry to bother me. It was probably nothing. A bit silly really but Ruud has been coming back in the evenings and disappearing into the treatment room. It’s all just a bit peculiar.

I turned and made my way to the treatment room to find Derek. He was cleaning. He was always cleaning. I passed on her message to him. His thoughts mirrored mine.

‘Fuck me, you don’t think he’s bugging the treatment room, do you?’

It felt like we were being ridiculous but the manager’s comments to me in the changing room and him coming back into our room at night when we’d all gone home were harmless enough in isolation, but together? Together they were enough to have the club’s longest-serving and most dedicated member of staff finish his day at work with his head stuck through a hastily removed roof tile with his flashlight in hand while I felt my way around the skirting boards, under the treatment tables and behind the desks. We didn’t find any bugs and through our laughter we agreed that we were now in danger of becoming ridiculously paranoid.

I got some respite from the madness when my father’s health deteriorated and Denise said it would be a good idea if I came home. He’d suffered from heart failure for many years. I got home just in time. Denise brought me into his room in a downstairs bedroom in her house. The single bed he was in dwarfed him.

Never a tall man, he now looked more like a baby who was spending its first night in the big bed after outgrowing its cot. I knelt by his bed and he opened his eyes.

‘Paul. You’re home, son.’

I told him I loved him but don’t think he heard me. He didn’t speak another coherent sentence in the morphine-induced stupor he spent his last week on earth floating in. My whole family were with him when he took his final breath. I cradled my niece Coleen

as a hideous rattle signalled his end. As my family gathered around him to kiss him goodbye I slipped unnoticed around the back of them and left the room. For the three days he lay in his open casket I stayed out of the room. The image of one dead parent burned into my skull was enough for one lifetime. He’d finally gone to where he wanted to be since the day the light left his life twelve years before. I was happy for him. He was finally at peace.

Denise’s house and garden were awash with flowers and wreaths. I read them all and then read them all again. They were from family, friends, distant relatives, my brothers’ employers, which were mostly local taxi firms. There were wreaths from Ireland, England

and New Zealand. It was like everybody wanted to pay their respects to him and to my family for our loss. The only one missing was the Newcastle United wreath. There was nothing. Not a flower, a card, a phone call. Nothing. I was embarrassed more than anything. An acknowledgement would have said so much. It would have meant so much.

Instead its absence told me everything I already knew. I was still raw from nursing my father in his final days when I arrived back for work in Newcastle. I was getting changed on my first morning back after my week long absence when Ruud strolled in.

‘So. Also. How is Didier Domi’s calf this morning?’

I stared at him. ‘Sorry, I don’t know.’

I knew it was probably nothing more than absent-mindedness on his part. He was a manager of a Premier League football club and had enormous demands to contend with every day. It was a perfectly legitimate question to ask of a physiotherapist sitting in front of him in the dressing room.

But at that moment – that very moment – I knew I needed to get out of professional football. I was done with it.

Having spent the past week nursing my father, and being surrounded by the love and support of my family, I could no longer stay in the world I’d worked so hard to be a part of. It suddenly felt pointless to me – a cold and harsh place that I needed to escape from – and all because the manager had asked me an entirely reasonable and innocent question.

‘You don’t know? What d’you mean you don’t know?’

‘Sorry, I don’t know. My father died and I’ve just come back today. I’ll ask Derek for you.’

Ruud offered his condolences and disappeared. I left the room and made my way to the treatment room. Thoughts of my father, my family, and just how exactly I was going to find my way to a better world accompanied me with every step I took.

The prospect of an FA Cup semi-final lightened the mood but I was still unsettled at times by some of my conversations with the manager. I made my way into the shower the day before we set off for our meeting with Tottenham Hotspur. Ruud was already there.

‘So. Also. Tell your friend he’s the best centre forward in England.’

I turned the handle and was hit by a jet of ice-cold water. ‘What?’

He turned his off and grabbed a towel. ‘Tell your friend he’s the best centre forward in England. I think he’s lacking a bit of confidence at the minute.’

I stepped back from the icy torrent. ‘Are you serious?’

He grinned. ‘Of course I’m serious. Tell him.’

I lost interest in the shower. ‘You want me as a physio to tell the England captain he’s the best centre forward in England? He’d tell me to fuck off and mind my own business and he’d be right. I don’t think Alan Shearer has ever lacked confidence. I won’t do that.’

He dried himself off while humming a tune I didn’t recognise.

I left without showering and spent the rest of the day trying to understand the point he was making. Alan’s spectacular goal to win the semi-final was achieved all on his own without the pep talk from a confused physiotherapist.

It wasn’t the only time I was bemused by Ruud’s actions. I arrived at Wembley Stadium for the FA Cup Final against Manchester United, the biggest game of our season. I sat on the bench to get changed and felt grains of sand beneath my thighs and on the floor at my feet. Ray Thompson, the kit manager, came in with a cup of coffee in his hand.

I raised my palm with the grains stuck to it. He looked over his shoulder to make sure we were alone.

‘You’re not going to believe this, man.’

He sat down beside me.

‘Why’s there sand everywhere, Ray?’

He shook his head. ‘It’s not sand, man. It’s salt.’

‘Salt?’

‘The manager’s had me sprinkle salt everywhere to ward off evil spirits ’cos he thinks the club’s cursed.’

‘Fuck off.’

‘Seriously, man. I’ve been chucking it everywhere.’

We were well beaten by Manchester United on the day. I don’t think a ‘curse’ had anything to do with the result.

The summer came and those staff members who’d aligned themselves to Ruud’s regime were quietly rewarded with pay rises, doubling their salaries in some instances. By the time we came back for pre-season I was very clear about one thing. I wanted the manager sacked. I hated myself for it but I wanted him gone.

My relationship with John Carver was strained to breaking point. He was part of a regime that was making my life a misery and in my opinion ruining the club. I’d watch my long-time friend regularly disappear into Steve Clarke’s house while I sat across the street and worried for my job and my family’s future.

I had good reason to be worried. In the week leading up to playing Sunderland, our biggest rivals, I was at the training ground. I was chatting to my friend and colleague Kevin Bell. Ruud approached us and spoke through a beaming smile. He looked me in the eye.

‘When I am in a stronger position, all of the shit will be gone from here.’

He held my gaze in uncomfortable silence before heading off and leaving us to stare at each other. Kevin fuelled my fears.

‘Jesus Christ man. I think he means you.’

The day before we played Sunderland at home I walked into the staff canteen. Ruud, Steve and John were sitting on a table to the right as I made my way to the breakfast buffet. Ruud was leaning back on the chair, balancing it on two back legs. He had a wide smile on his face and spoke loudly so that I could hear.

‘It’s a new dawn for this club tomorrow. New day. Fresh start. The future is bright. The future begins tomorrow.’

It was unnecessary and childish. He was gloating over his decision to drop Alan Shearer for the big game.

By all means do it if that’s what you want to do but this sort of behaviour was crass and uncalled for. By the time I took my seat in the dugout I was desperate for our biggest rivals to beat us in our own stadium.

I was ashamed of myself but I knew the heart and soul of the club was at stake. I felt my job was at stake. When I got home long after the monsoon had rained on Ruud’s parade I watched the manager blame Alan Shearer for the result even though he’d left him out of the team in the first place. He gave the world a glimpse of the arrogance and wrong-headedness of his tenure at the club.

I knew that once he’d done that there was no way back for him. The club would be better for it. I spoke with John after Ruud left. I fully understood the awkward position he’d found himself in and his duty to be loyal to the manager who’d given him his first senior position. I was glad our friendship survived the absurdity of his tenure. I was relieved it was over but apprehensive about who would replace him.

‘The Boy on the Shed’ by Paul Ferris is published by Hodder. More info here.